eBook - ePub

Controlling Paris

Armed Forces and Counter-Revolution, 1789-1848

Jonathan M. House

This is a test

Share book

- 324 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Controlling Paris

Armed Forces and Counter-Revolution, 1789-1848

Jonathan M. House

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

· “Detailed and balanced history.” – John A. Lynn II, Distinguished Professor of Military History, Northwestern University

· “An important work on civil-military relations.” – Jeremy Black, University of Exeter

“A major contribution to our understanding of the instability and violence that were part of France’s experience.” – Robert Tombs, University of Cambridge

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Controlling Paris an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Controlling Paris by Jonathan M. House in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Déjà Vu

The Bourbon Monarchy Falls Twice

It is obvious that revolutions have never taken place, and will never take place, save with the aid of an important fraction of the army. Royalty did not disappear in France on the day when Louis XVI was guillotined, but at the precise moment when his mutinous troops refused to defend him.

—Gustave Le Bon1

—Gustave Le Bon1

Policing Paris

In accordance with its status as the premier city of France, Paris was the first urban area in the country to develop a police structure. In the eleventh century, the prévôt de Paris became the overall administrator of the city, an office that evolved over the ensuing centuries to include a force of night watchmen, the Guet.2 From the beginning, however, the term police meant much more in France than the Anglo-Saxon definition of that word. In addition to law and order, the work of the police of Paris included public health, building inspections, fair-trade practices, control of vagabonds, public decorum, and a host of related administrative matters.3

Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s finance minister, institutionalized these responsibilities in two decrees, dated December 1666 and March 1667, with the latter creating the twin offices of lieutenant-civil and lieutenant of police for Paris. As was usual in the venal structure of French royal government, Gabriel-Nicolas de La Reynie purchased the latter position for 250,000 livres, and Colbert authorized a Guet of 144 horsemen and 410 foot troops (sometimes referred to by the archaic title of archers) to enforce the lieutenant’s orders. From the start, La Reynie was much more of a judge and administrator than a police chief. Over the next several decades, he acquired further titles—such as chevalier de Guet and lieutenant general of police—and responsibilities, including a network of informers as well as street lighters and cleaners.4

By the later 1700s, the lieutenant general of police had become one of the highest-ranking administrators in France, reporting to the court system (Parlement de Paris) on some matters and directly to the king on others. At the same time, the Guet, while still retaining its antiquated name for some purposes, had grown and become the Garde de Paris, which by 1789 numbered 265 horsemen and 1,190 foot soldiers. Although the mounted police were quite experienced and professional, there was a high turnover among the foot police, who in effect were serving an apprenticeship to become horsemen. Meanwhile, noblemen and even their servants sometimes defied the Garde de Paris, insisting that they were not subject to its administration. Jean Chagniot has argued that, in fact, the Garde was inhibited by fear of public reaction, so that it sometimes hesitated to use force.5 Still, after the crown dissolved the two companies of gentlemen musketeers in 1775, the Garde provided the only mounted troops in the city, an important consideration in case of crowd control.

There were also a variety of police inspectors, gardes de ville, and commissioners of police to perform specialized duties within the city. Overall, Alan Williams has calculated that on the eve of the Revolution the police employed 3,114 men, of whom 1,931 were the equivalent of modern patrolmen and investigators. If the population of Paris and its suburbs was approximately six hundred thousand, this meant a ratio of one policeman for every 313 residents, a very high proportion for the early modern era.6 Moreover, the constant efforts of the police to ban the use of firearms had greatly reduced the availability of weapons among the city populace.

Beginning in 1720, the royal government also sought to regularize the rural marshals or constables of France, the Maréchaussée. Eventually, all recruits for this mounted police had to have served sixteen years in the army, giving them a maturity and experience not always found among the urban police. Retired members of the rural force came to have the same status as army veterans, a status rarely granted to retired members of the Guet or Garde. By 1789, there were approximately 410 Maréchaussée in the suburbs of Paris, where they generally operated in “brigades” of five men.7

With the exception of the Maréchaussée, the royal structure for public order was, like the rest of the Bourbon government, a patchwork of offices and titles, many of them requiring the incumbent to purchase his office at each new generation. Sometimes, while there were other administrators who ran the courts of Paris, the offices of chevalier de Guet and lieutenant general were united in one person and sometimes they were separated. Again, such a confusion of titles and organizations was quite common in the ancien régime. Long after the militia of Paris ceased to function, one could still purchase militia ranks that carried certain privileges with them. Nonetheless, the key officials were generally competent and experienced in their positions. In the last decades before the Revolution, the government tried to improve professionalism by suppressing venality within the Garde de Paris, but the reforms were far from complete. Even the foot troops of the Garde de Paris could not easily live on their daily pay.

The Army’s Role

For a century ending in 1762, the household troops of the Bourbon monarchy had, on average, marched off on campaign almost one year out of every two. As a result, although they occasionally became involved in maintaining domestic order or fighting major fires, it was unrealistic to rely upon the army for such functions. Indeed, this was one reason why Paris developed its own security forces and why there was no permanent military commander of the city. Some observers of the efficiency with which the Guet and later the Garde controlled Paris believed that Parisians were unwilling to revolt. Moreover, the commanders of the guards regiments insisted that they were not answerable to anyone but the king and would not accept orders from any other authority. Then, in the final three decades of the ancien régime, the guards came home to roost, and gradually became drawn into police functions.8

In addition to several bodyguard units, the royal household troops consisted of two principal regiments, the French Guards (Gardes Françaises, thirty-six hundred men) and the Swiss Guards (Gardes Suisses, twenty-three hundred men).9 Elaborate treaties between France and the Swiss cantons governed the rights and privileges of the latter, whereas the former was a unique—and uniquely unstable—organization.

A number of policies affected the French Guards after the Seven Years’ War. The government made a conscious effort to recruit nationally for the organization, so that only a minority of guardsmen were native-born Parisians. Moreover, beginning in 1764, the guardsmen were gradually moved out of individual lodgings and concentrated in multi-company buildings, a form of mini-barracks, generally on the western side of the city, closer to the royal court at Versailles. An unpopular tax on homeowners, raised in lieu of actually quartering the troops in their homes, paid for these buildings. Soldiers below the rank of sergeant were forbidden to marry, in order to keep them in the barracks. Despite this effort to isolate the troops, the long period of residency in one city meant that the French Guards were in daily contact with the populace and often shared their social and economic concerns. Moreover, the troops were so poorly paid that many of them sought additional employment in their off-duty time, again bringing them into contact with civilians. If anything, the concentration of troops into barracks may have encouraged the spread of mutinous ideas within the regiment during the crisis of 1789.10

Traditionally, the noblemen who served as officers in the French Guards changed companies each time a vacancy in another company permitted them to purchase a higher rank; as a result, these officers had relatively little contact with their troops, so the career sergeants provided continuity and leadership. For decades, French Guard sergeants had achieved promotion, often quite rapidly, based on merit.

This changed in the later 1760s, when an effort to make the guards into a Prussian-style well-drilled machine undermined the cohesion of the unit. First, all new recruits, even those with prior service in other regiments, had to attend an extremely harsh five-month training depot. This led to increased desertions and occasional suicides among the French Guardsmen, and even some of the Swiss deserted. Of almost equal significance was the fact that the promotion pattern for noncommissioned officers changed. Increasingly, promotion to sergeant went to the instructor corporals in the training depot rather than to candidates from within the Line companies. By 1789, the French Guards had far more grievances than effective leaders, which goes far to explain why so many companies first refused to fight and eventually joined the uprisings.11

Meanwhile, the dividing line between military and police gradually crumbled as civil authorities repeatedly pressed the household troops for assistance. Details of guardsmen policed not only the theaters and opera, whose aristocratic patrons refused to obey the civilian police, but also public markets. Household troops also stood guard outside ministers’ homes and sometimes arrested noblemen. A decree of 1782 required the guards to protect the tax collectors at the octroi gates, the hated tollbooths at the entrances to Paris that collected taxes on all goods entering the city. By 1785, the French Guards Regiment had up to a thousand soldiers per day, almost one-third of its strength, on such police duties. The regimental commanders were often able to negotiate special fees for such services, so that at least the sergeants in charge of these details profited from the additional duties.12 However, these fees in effect changed the attitudes and cheapened the status of the guards, as if they were modern policemen supplementing their pay with second jobs as security guards. Similarly, the military retirees of the Invalides received additional pay to guard banks and other public institutions.

By the later 1780s, the public had become so inured to the sight of troops in the streets that it had come to regard soldiers as indistinguishable from the hated police. The frequent use of the royal army in such a situation tended to reduce the legitimacy of the regime in the eyes of its people. Even where the troops did not sympathize with agitators, they were far less likely to command compliance from those agitators. Confrontations might quickly move to violence; beyond the flat of a sword, the troops had nothing short of deadly force to enforce order.

Revolutionary Geography

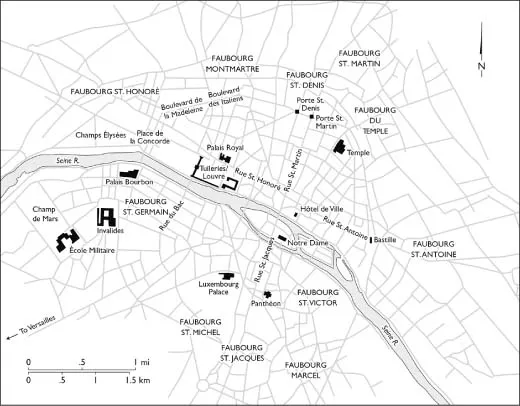

Before examining the long history of disturbances and revolution, it is appropriate to describe the geography of Paris before Baron Georges-Eugène Hausmann rebuilt the city for Napoleon III in the 1850s and 1860s.13

The classes of Parisian society were heavily intermingled. It was not uncommon to have a retail establishment on the street floor of a building, a middle-class family living on the second floor, and some mixture of family servants, artisans, and laborers on the upper floors. Even in the central government district immediately north of the Île de la Cité, artisans had homes and workshops interspersed with offices and newspapers. While Paris developed extensive industry in the course of the nineteenth century, most of that industry consisted of small enterprises each employing only a handful of workers. In 1848, for example, seven thousand businesses employed more than ten workers each, while thirty-two thousand businesses consisted of one to two workers. Only the advent of railroads toward the periphery of the city added a significant industrial element.14

Paris in 1789

Having said that, the city still had a vague pattern of economic and social structure, and by the 1840s, it was beginning to evolve, very slowly, into neighborhoods divided by class. Generally speaking, the northern and western portions of the right bank had a higher proportion of wide boulevards and well-to-do residents than the central and eastern portions of both banks. The majority of large open areas where people congregated, including squares and parks, were also found in the northern and western areas as well as the governmental center. In turn, the eastern and southeastern sectors tended to be more heavily settled with artisans and laborers and attracted more internal migrants from the provinces. As early as the 1790s, therefore, the northern and western portions of Paris tended to be more moderate politically, while the more extreme advocates of economic and social change often came from the eastern and southeastern portions of the city. Although narrow, twisting streets were common throughout the city, such streets predominated in the latter areas, where they made armed resistance easier and maintenance of public order more difficult.

Causes and Patterns of Behavior

As in any military operation, the first challenge for a government seeking to defeat rebellion was accurate intelligence about the threat. Although France had an effective political police even under the ancien régime, it is no accident that all post-1789 governments were preoccupied with secret agents who could give them advanced warning of threats to the regime, whether in Paris or the rising industrial towns. The quest for such warning leads us to the causation of revolution.

The vast literature on the causes of the French Revolution, and for that matter of the subsequent revolutions of 1830 and 1848, lies beyond the scope of this study. Certainly, the three revolutions occurred as part of cycles of resistance to central authority. Beyond that observation, successive generations of historians have chosen to emphasize different combinations of economic, social, political, and ideological factors motivating different groups within the population.15 In discussing these causes, I will attempt to provide sufficient background to place violent acts in context, but I cannot pretend to resolve the historiographic controversies of two centuries.

Nor do I wish to take sides between those who explain collective violence as the breakdown of society and those who argue that it is the expression of solidarity among interest groups.16 Contemporary government officials may have tended to the former explanation, blaming urban disorder on the flow of rootless people from the provinces, but even if this diagnosis informed government actions, it was not necessarily accurate. By 1848, Karl Marx was famously attributing conflict to class warfare, even though these categories were anachronistic in Paris, where the actual rebels could hardly be categorized as proletarians. If anything, I subscribe to the law of unintended consequences: each side in a confrontation had varied and perhaps ill-defined expectations; the interaction of different factions both within and between the two sides as well as pure chance sometimes produced an outcome that neither had anticipated.

Nonetheless, some working hypothesis is necessary to explain why uprisings occurred, let alone succeeded or failed. Let us begin, therefore, with the fact that the preindustrial cities of Europe, and especially Paris, were subject to constant stresses of social dislocation and economic suffering; only the degree of desperation varied from year to year.17 The steady migration of people from all parts of France to the capital provided a body of young, often disadvantaged workers, who were both unknown to the police and unsupported by a family or neighborhood structure. Yet the truly destitute were rarely interested in something more serious than a bread riot; if anything, it was the lower middle class, people of substance with families and businesses at risk, who were most likely to be active in their communities and in the streets.18 Still, most governments had the authority and power to control strictly economic unrest, albeit sometimes only by resorting to violence.

Imagine, however, that this economic and social agitation represented the flow of current passing through a transistor of urban conflict. When a major signal of political and ideological confrontation was superimposed onto this flow of economic and social unrest, the effect was to greatly amplify that signal as a threat to the state. By itself, even this amplified output might still fail to overthrow the regime, but it certainly set the stage for the unforeseen events that led to true revolutions. This is not to suggest that one social group co-opted another, or even that these groups understood and supported each other’s issues, but rather that accumulated anxiety and frustration could become commingled, often with unforeseen outcomes. To mix metaphors badly, the bridge between the political and the economic, between the opposition politicians and the street crowd, was often that the lower middle-class had interests in both worlds.19

Regardless of the degree to which this model is congruent with traditional historiography, this discussion suggests two issues that are at the center of this ...