![]()

1 Back in the Day

Linda Jackson had never wanted to be involved in politics. As “a preacher’s kid,” she was in church seven days a week doing community work. When she left home she swore, “I was never going to participate in anything else. That’s the end of it.” But she got “thrown back into” community work as white flight and economic decline hit Elmhurst hard in the 1970s and ‘80s, and she watched her neighborhood struggle with crime and blight that erased the precarious distinctions between middle-class and poor in East Oakland. Over twenty years later, when I first visited her home, Linda Jackson was frustrated by the city’s failed promises, fed up with ongoing problems of drug dealing and violence, and angry at “this generation of kids that’s out here shooting up people.”

Linda Jackson spoke with the rhythmic cadences and broad vowels of Arkansas. “I’m just a simple little country girl,” she’d say in community meetings, before her voice took on a steely tone, her impatience with city officials shining through an otherwise polite southern demeanor. An African American woman in her mid-sixties, she had attended a state college in Arkansas soon after it was integrated, retired from administrative work at a local hospital, and now ran a small family construction company with her husband out of their home.

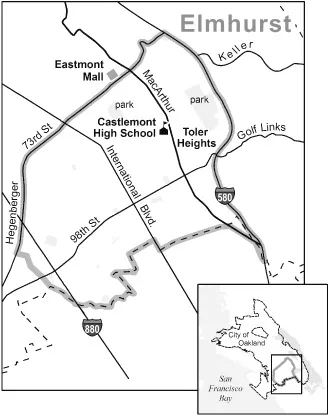

Mrs. and Mr. Jackson raised two children, and they now watched anxiously as their two grandchildren negotiated the transition through their teenage years in East Oakland. Their ample 1940s bungalow nestled into a low hill in Toler Heights, a predominantly black middle-class community where many neighbors worked in professional or government jobs, but others lived below the poverty line. Only one block away lay the run-down 1970s apartment buildings, liquor stores, and mostly empty store fronts that cluster along MacArthur Boulevard in the sprawling and much poorer flatlands of Elmhurst.

Mrs. Jackson first joined her homeowners’ association in the 1970s after a series of robberies in her neighborhood. They created a neighborhood patrol and built a close relationship with the police department. One meeting and committee seemed to lead to another, until soon she was spending evenings and most vacations working with the association, the Neighborhood Crime Prevention Council, and neighborhood redevelopment efforts. As her grand-kids began to go to the neighborhood public schools, she was drawn towards working with the schools as well.

Figure 3. Map of Elmhurst: In the Flatlands. (Mark Kumler and Diana Sinton, University of Redlands)

By the time we sat down in her home to talk, Mrs. Jackson had long been a leader in neighborhood politics. She regularly spoke in front of the city council, gave interviews to newspapers, and organized with a strong network of neighbors to crack down on cruising, drug dealing, and violence throughout East Oakland. “All of us that are participating own our homes. We have chosen to stay here. We could have left but we decided not to. We decided we’re no longer going to be ignored.” She described East Oakland as the city’s “forgotten stepchild.” “People will come out and give us a lot of lip service, canned speeches. You know how many plans they’ve had out here?” She was fed up with watching those plans pile up, unfunded and never implemented.

“What people seem to forget is that we all have a stake in this. I heard the most ridiculous crazy man on the radio. He said he wasn’t interested in education because he had no kids. This man better be interested.” She knew the effects of public disinvestment. “These kids that you’re leaving behind without education will be your worst nightmare in the future. The have-nots are going to be coming up robbing you.” She looked back at the massive budget cuts to cities “during Reagan’s time” and saw the results all around her neighborhood. “All of us have paid a price for it.”

Mrs. Jackson had grown up in a strict southern household and worried that parents today weren’t instilling the proper discipline in children. Her parents had raised five “strong-willed” children back in Arkansas and taught them that “you had to earn what you get.” Growing up poor, she remembered picking cotton to pay for her own school clothes. “Not a one of us went to jail. All of us have been self-sufficient. We left home seventeen, eighteen. None of us ever returned home to depend on our parents to take care of us.”

“My mom used to tell me, ‘I wasn’t brought here to be your friend. I was brought here to train you the way you need to be trained.’ They kept me so afraid to do certain things until I got old enough to know better.” She laughed. “I just figured if I did certain things, my parents would kill me.” Nowadays, “these kids don’t think anything would happen to them. In fact, the parents will be the first one running out there to jump on you if you say anything to them.”

Mrs. Jackson’s own kids had passed through adolescence safely. Raising kids amidst the deepening poverty, anger, and desperation of East Oakland was not easy, and drugs and violence were too close to ignore. “Everyday I thank my lucky stars that my son is not one of those kids out there on the corner, shooting and selling dope, that my daughter did not fall into that bag, getting pregnant, getting on welfare and never getting off. To me that was a certain amount of success.” Her nephew, “a perfectly intelligent young man, got off into drugs,” and after years in and out of treatment, was “back on the streets again.” Her voice echoed the whole family’s disappointment as she talked about waiting to hear about his imminent death. “I would have thought if anyone could get off of drugs it would be him.”

Maternal vigilance and the iron hand of her husband had kept her own kids on the right path. “When my son was growing up, he was always devilish.” She laughed. “I made sure I knew where they were.” She often drove her son to school or picked her grandson up, so that they wouldn’t be tempted by the streets. “If I had to get in the car and follow them, I did. I would come down and get them off that corner. . . . It took them awhile to know how I knew so much.” Mrs. Jackson “talked her children to death” explaining the long-term consequences of the choices they made. But she also made sure they knew that child abuse laws didn’t mean she couldn’t discipline them. One day, she invited a police officer to come tell her children, “If your mama wants to whop you, I’m going to hold you down.” “That took care of that problem,” she explained.

But Mrs. Jackson still worried as she thought about her kids’ futures. They had avoided the most obvious pitfalls. “They both work, and they are pretty well self-sufficient.” But they still struggled. Her son had dropped out of college only a few units shy of graduation to take a job at UPS, and he had recently “hit a brick wall” trying to get promotions in the company. While other guys were given permission to return to college while retaining their job, he wasn’t. He quit in frustration and started working for the family business. He now understood what his mother had always been telling him: “You’ve got to get yours before you get there.” “I don’t think parents teach kids this enough. If you’re black you better make darned certain you are three times better qualified. Expect to be knocked down three to four times when you go out there. . . . We have to prepare ourselves.”

Mrs. Jackson and her husband had helped the kids through rough patches—through divorce, a lost job—and they would do so again. “I would like them to be able to buy their own house by now, to own their home, but they do have their own apartments. I do understand in this day and age it is really hard for kids to do that. At some point in time, I may have to help them with a down payment.” Mrs. Jackson’s daughter struggled to afford the escalating cost of renting an apartment in Oakland despite income from two part-time jobs. A divorced single mother of two whose husband didn’t pay child support, she had recently complained about her mom’s community work: “Mom, you’re running me out of town.” Mrs. Jackson acknowledged, “It’s true”: economic redevelopment might displace “some of the good people.”

Mrs. Jackson measured her children’s success against the extraordinary risks that face black children coming of age in contemporary American cities. In Elmhurst, the children of many black homeowners had made it securely into the expanding black middle class. Some had moved to the suburbs and urged their parents to follow. But many others had struggled to finish college and maintain jobs, and some remained living at home far into adulthood. On almost every block, one could hear about some neighbor’s child who had grown up too soon, about children raising children, or some young relative who fell into drug dealing, drug abuse, or jail.

Mrs. Jackson worried even more as she watched her grandkids, still in an awkward stage between childhood and adulthood. She and her husband were paying for their granddaughter’s apartment for one year while she enrolled in an LPN nursing program, while still maintaining hope that she would achieve her dream of becoming a doctor. But if she didn’t apply herself, they would end their support. “With kids these days, people are too lenient. You have chances. You can make good choices.” Her grandson, then seventeen, loved to make comic books, but had not been applying himself in school. She had warned him recently, “You are making choices that will affect you in your life. We’ll be disappointed. But you will pay the price.” He had finally decided he wanted to graduate, but she knew he wasn’t safe yet. “He’s still at an age where he could get drawn into some of this craziness out here. I’m hoping that he doesn’t.”

Mrs. Jackson insisted that the neighborhood needed a long-term economic development plan. She wanted the city to build a youth center so that young people would have some alternative to “the temptation and trouble” they could get into hanging out on the street. But she worried that the neighborhood would never be able to attract any investment “if you have people shooting things up at night and there’s no control. . . . We need the policemen right now to keep things under control. We realize that the policeman is not the answer to our problems, but they’re the Band-Aid until we can get some things accomplished.”

She didn’t worry much about racial profiling because “the people perpetrating these crimes are our young black men in our neighborhood.” But she acknowledged that black men in her homeowners’ association were often “very leery of giving the police too much power.” Even her husband had recently objected to her support for random police sweeps down MacArthur Boulevard. “Well, I haven’t done anything,” he insisted. But she explained, “Well, this is the situation: either we continue the way we are, or we allow the policemen to make things safer for us.” She told him to avoid driving on MacArthur and if he was stopped, to do exactly what the officer said. “It’s amazing, he came to realize—those were the choices.”

Disciplining Youth and Families in the Flatlands

Back in the days, our parents used to take care of us Look at ‘em now, they even fuckin’ scared of us Callin’ the city for help because they can’t maintain Damn, shit done changed.

—Notorious B.I.G.

In February 2001, one of the Elmhurst Neighborhood Crime Prevention Councils (NCPC) met in a classroom at a local middle school. Bill Clay, the dapper African American NCPC president, invited two uniformed community policing officers, a tall, broad-shouldered white officer and a heavyset Asian officer, to sit up at the front of the room with him, “on the hot seat.” The officers explained that they had been doing a lot of violence suppression in response to the recent rise in homicides, “flooding” particular areas with as many as twenty-five officers and “stopping everyone we can.” They were targeting parolees and conducting undercover buy-bust operations at drug hot spots. Mr. Clay then told the officers to take out their pens and asked for community concerns: “Who’s got the first problem?”

Mrs. Gilbert, Mr. Lawlor, Mr. and Mrs. Riles, Mrs. Taylor, and her granddaughter sat around tables with fifteen other people facing the front of the room where pictures for Black History Month surrounded the blackboard. Older African American homeowners formed a clear majority of members in the NCPC, but they were joined by a couple of white senior citizens, younger African American homeowners, one older Latino homeowner, an Arab business owner, and the school vice-principal and a code compliance officer, both African American. This NCPC was typical of most in Elmhurst. A small number of people came monthly, but more would turn out for meetings with the police chief or city manager. This NCPC could reach as many as two hundred residents through its homeowners’ associations, block captains, informal phone trees, and relationships among neighbors.

Residents began to describe problems with drug dealing at specific addresses, sometimes using drug dealers’ nicknames and offering details about where drugs were hidden and when drugs were sold. Mrs. Gilbert complained that she had to move her granddaughter’s bedroom to the other side of the house so she wouldn’t hear drug dealers’ conversations from next door. “All the dealers in East Oakland are at that address.” Mrs. Taylor disagreed; she still had a lot of dealers on her block. James Richards, a black man in his midforties, was discussing persistent drug dealing at a local liquor store when Deputy Chief Bryant walked into the room. “They’re like cockroaches, the mess, the noise level is outrageous,” he said. Turning to the deputy chief, he added, “I’m talking about across from your mother’s home.”

A broad-shouldered African American man with gentle eyes, Deputy Chief Bryant responded that he knew the problem well. He had grown up in this neighborhood before moving to the Oakland hills. He still attended church, visited his mother, and mentored young people in the neighborhood. Bryant described his vision for how to address Oakland’s persistent problems with crime and violence. “We can’t resolve the problem by locking people up, and we have locked up a lot of folks in Oakland. OPD [Oakland Police Department] is good at that. In California we have tripled the prison population and darn near bankrupted this state by trying to lock people up.” He asked for volunteers to go door to door to promote a pledge of nonviolence, to hand out literature on anger management resources, and to recruit new members for community policing. The deputy chief hoped this new program would recreate the Elmhurst neighborhood of his childhood.

People will begin to talk to each other once again. . . . In 1968 when I was at Elmhurst Middle School, if I did something wrong, my father knew when I got home. We knew each other. We have gotten away from that. Tell me what my kid’s doing. This is about reaching out and building community from the ground up. The strength of the community comes from you folks. What we need is you.

Mrs. Riles, a black woman in her late seventies, spoke up. “The problem is that parents are afraid to chastise their children and teach them properly” because the kids might call the police on them. Deputy Chief Bryant insisted that the police only arrested parents in cases of serious abuse. “That’s just an excuse that I can’t handle. We have to get back to having children because we want to have them, and we want to raise them to be respectable parts of the community. Those values have to come from. . . .” He paused to wait for a response from the room. Mrs. Riles responded “home,” while another older African American man said “the village.” The deputy chief nodded, adding, “I am the most liberal deputy chief and definitely the only Democrat, but when it comes to raising children, Democrats have not done well. ‘Let the government deal with it. Let child welfare deal with it.’ We have to deal with it right here.” He called for neighbors to become mentors and for the neighborhood to become “its own policing system.”

This NCPC meeting highlighted a pervasive nostalgia in urban black communities. In almost every interview, I heard stories of a more orderly past when adults disciplined children, youth showed respect, and a more cohesive black community took responsibility for raising children as a village. African American activists in Elmhurst’s NCPCs did not represent a single generation, as they ranged in age from late thirties to eighties, yet in community meetings and conversations, they constructed a body of shared memories. Repeated stories captured their sense that something was wrong with young people today. “Young people today have no respect” or “no discipline.” “Youth have too much power.” “These children are taking over.”

Children served as vital sites of memory and nostalgic longing in Elmhurst. Anthropologist William Bissell argues that nostalgia is not “poor history” but a social practice shaped by specific spaces and politics in the present.1 We look to the past at moments when faith in the future or in progress is eclipsed. Nostalgia in Elmhurst highlighted deep ambivalence about whether the post–civil rights era represented true progress in the black community—especially when activists looked at the hurdles young people faced coming of age in the neighborhood.

Debates about children and childrearing encapsulated fundamental debates over the role of the state and the causes of black community struggles. Were the Democrats’ welfare programs responsible for undermining the foundations of black communities? Or had state intrusions into the family via child abuse laws undermined parental authority? Could the police solve the neighborhood crime problem? Or did the community have to take responsibility for discipline? Was childrearing the responsibility of parents in the home, as Mrs. Riles suggested, or of a broader “village”? These debates highlighted the complexity of black politics in the East Oakland flatlands and the ways activists combined different political ideologies. Nevertheless, nostalgia for disciplined youth shaped the politics of childhood in this neighborhood. Defining crime as a youth problem focuse...