![]()

1

Introduction

During the first few years of his life, my son, Sam, missed every developmental milestone. He walked awkwardly, had little speech, and was socially withdrawn. Shortly before his third birthday, his pediatrician diagnosed him as disabled. As a white middle-class mother who is also a legal expert in the field of special education, I have been able to devote enormous amounts of time and money to advocate for Sam since that time. Several years ago, I sued my local school district to attain the services Sam needs in order to have access to oral instruction. At age fifteen, he is flourishing. Sam is running cross-country, writing a science fiction novel, and enjoying social functions with his friends. There is little question that Sam would be foundering if he had been born into a less privileged household.

That is wrong.

In 1968, Professor Lloyd Dunn, one of the leading researchers and activists in the field of special education, argued that the practice of segregating “slow” students into special education classes was a “sham of dreams” because it simply resulted in poor and minority students receiving inferior educations.1 In 1974, Dunn testified in opposition to the proposed special education laws because he predicted that “these bills, if enacted, would do more harm than good for the very children they are committed to serve better.”2 Even though Congress was aware of Dunn’s important work when it devised the special education laws, it took few, if any steps, to deal with this possibility.

Thirty years later, one can find books with titles such as Racial Inequality in Special Education3 and Why Are So Many Minority Students in Special Education?4 that pursue the theme: What is so special about special education for poor and minority children? As predicted by Dunn, the authors of these books argue that poor and minority children often receive “inadequate services, low-quality curriculum and instruction and unnecessary isolation from their nondisabled peers.”5 African American children are likely to be overrepresented in certain disability categories and underrepresented in others. The special education classification system is often “the result of social forces that intertwine to construct an identity of ‘disability’ for children whom the regular-education system finds too difficult to serve.”6 Special education services for poor and minority children often arrive too late to provide significant assistance, are not tailored to remedy the actual deficits these children face, and may result in segregated services in highly inadequate educational environments.

The story for children in middle-class families is less problematic but still troubling. These children are more likely to live in school districts that offer adequate programs for children with special needs. Nonetheless, if their school districts are not offering an appropriate education for children with disabilities, the resources needed to use the special education laws to challenge inappropriate educational practices are out of reach for most of their parents. It often takes expensive and time-consuming advocacy with the assistance of professionals for children to receive an appropriate education.

This book will try to help the reader understand why the special education system is not so “special” for many children. The reasons are complex and no longer due to de jure exclusion from public schools that was common until the 1970s. Instead, rules like the expectation that a parent act as an advocate for a child disproportionately harm poor children whose parents do not have the time or skill level to act as effective advocates. The highly subjective disability classification system has led to minority children being disproportionately classified as emotionally disturbed or mentally retarded7 and exiled into weak educational settings, and white children being disproportionately classified as autistic or developmentally delayed and sometimes placed in strong educational programs. The special education system is also woefully underfunded, especially in school districts that serve poor children. Although Congress has tinkered with the rules over the years, sometimes even in response to concerns about racial equality, these changes have been largely ineffective. And some changes, like the strengthening of school districts’ powers to discipline children with disabilities, have disproportionately harmed poor and minority children, particularly African American youth. This book seeks to uncover the history and impact of these and other seemingly neutral rules on the educational experiences of poor and minority children.

The following two stories drawn from my experience and that of another family in Ohio illustrate the difficulties for any child to receive appropriate special education assistance and how those difficulties are compounded for children in poor families.

Sam was born on January 9, 1997, in a suburban community.8 Soon after he was diagnosed as disabled, the school district enrolled him in an excellent special education program for preschoolers where he made enormous progress.

Even with some extra help, Sam continued to face difficulties during grade school. In particular, he was having a lot of difficulty following classroom instruction. After I co-taught a special education class with an audiologist, Dr. Gail Whitelaw, and shared with her my struggles with Sam, she suggested I bring him to her clinic to be tested. That testing was covered under my health care plan. Whitelaw concluded that Sam had central auditory processing disorder (CAPD).9 She explained that the consequences in the classroom for a child with CAPD are comparable to those of a deaf child because the child misses so much oral instruction. She recommended that the school district acquire a personal listening device (PLD) for Sam to use in the classroom, along with other accommodations. A PLD brings the sound directly to the child’s ear through an FM receiver and costs about $1,000.

The school district agreed that Sam was disabled but refused to provide him with a PLD. After a year of being stonewalled, I filed a due process complaint against the school district under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Under the IDEA, parents who file due process complaints are encouraged to seek a resolution through mediation. If mediation is unsuccessful, parents can then bring their case before a hearing officer, who is an administrative law judge hired by the state to conduct such hearings.

I retained two expert witnesses and a lawyer to assist me with mediation. After mediation was unsuccessful, these individuals also helped me conduct a three-day hearing. On the Friday before school was to start, and two years after Whitelaw recommended Sam have a PLD, the hearing officer sent her decision to the parties and their lawyers. She ruled in Sam’s favor, concluding that the evidence conclusively demonstrated that he needed a PLD to access oral communication. She gave the school district thirty days to acquire a device and implement a revised Individualized Education Program (IEP). The school district ultimately complied, and Sam’s performance in school began to improve dramatically.

Although Sam’s story is a success under the IDEA, it is hard to understate the difficulty and stress of filing a due process complaint, even for someone with my level of expertise. As it happened, I filed for the due process hearing at a time of enormous strain in my life. I had broken my femur several weeks before the hearing and was extremely uncomfortable during the lengthy hearing. The lawyer I hired to assist me was diagnosed with stage-four cancer shortly after the hearing ended and could not help me implement the order. My mother, who lived in another city, was dying of cancer that summer, and I was trying to spend as much time with her as possible. And my daughter was getting ready to go to college. But even if those personal circumstances had not been in place, hiring experts, preparing the lawyer for the hearing, and sitting through a week of hearings were very difficult. The wait for the decision seemed interminable. The process was also quite expensive. Although I was reimbursed for most of my attorney fees, I had to pay for the two experts. Advocating for my son was one of the most stressful experiences of my life.

* * *

At about the same time as I was pursuing my case through the state administrative system, another mother, Marilyn, was pursuing a case involving her son Kevin in a different school district.10 (Both names are pseudonyms.) She was unmarried, pregnant, and unable to afford an attorney. The school district had identified her son as being emotionally disturbed and having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Kevin had been taking medication to help moderate his behavior and reduce his symptoms but had stopped taking it for a period of time when his mother could not afford any medical treatment for him. He also had a behavioral intervention plan to help him maintain appropriate behavior in the classroom. When the school district threatened to suspend Kevin for violating school policies, his mother filed a due process complaint in order to get the school to recognize that his misbehavior was a result of his disability. She wanted a more effective IEP that would address his educational needs and keep him in school.

Marilyn initially requested an expedited hearing to avoid having her son suspended from school. The hearing, however, had to be put on a regular schedule because illness and childcare responsibilities precluded her from maintaining the pace of an expedited hearing. Marilyn’s brother attended the due process hearing with her, trying to offer assistance even though he was not an attorney.

The hearing officer ruled for the school district, finding that it was offering Kevin an adequate IEP and handling his behavioral problems appropriately. In ruling for the school district, the hearing officer noted that the mother “seemed exceptionally frustrated and intimidated by the due process hearing procedures.” The parent had no idea how to write a brief and began leaving long voicemail messages on the hearing officer’s telephone with the arguments she wanted to make. Then, after the deadline had passed for submitting a brief, she left further messages with statements such as “Just going to let you make decision. . . . Too stressful on me and my children and my unborn baby.” The hearing officer—who never received any kind of brief from the parent—ruled, as noted, in favor of the school district. Kevin’s reasons for causing trouble in school and what kind of IEP might provide him with an effective education were barely explored.

The difference in treatment that Sam and Kevin received is typical of the stories that this book will explore. Both Sam and Kevin had trouble paying attention in school. Sam saw a private audiologist who diagnosed him with CAPD and helped him get a PLD. Even though the school district fought me over the PLD issue, they did give Sam lots of support to improve his performance and were patient when his behavior was sometimes socially awkward. Kevin, by contrast, was labeled as having ADHD and being emotionally disturbed. He did not get the academic support he needed and was suspended when he violated school rules. I was able to hire a lawyer and two expert witnesses. Kevin’s mother could neither participate in an expedited hearing schedule nor file a brief. No system was in place to provide Kevin or his mother with a free advocate. While Sam soon flourished in school, Kevin was suspended.

How did we attain a process that is so heavily biased against low-income parents like Marilyn whose children need assistance in comparison with a mother like me who has expertise in the subject and can afford to spend the time and money to assist her son? Why do we have a statute that requires families to make advocacy a full-time job in order to prevail? That is the story I will tell in this book.

* * *

When Congress adopted the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA) in 1975, which was subsequently renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, it sought to improve educational equity by helping children with disabilities. Since the enactment of the EAHCA in 1975, 90 percent fewer children with developmental disabilities are living in institutions.11 In 1975, more than 1 million children with disabilities were excluded from public school; today, virtually no child with a disability is excluded from public school.

Nonetheless, the enactment of the EAHCA may have also increased educational inequity. Congress has never fulfilled its promise to provide 40 percent of the dollars needed to educate children with disabilities; instead, federal underfunding of special education has exacerbated an inequitable allocation of education resources. Certain racial minorities are disproportionately identified as belonging to particular disability categories; those categories are often also the most stigmatizing. And, irrespective of their disability classification, racial minorities, who are disproportionately poor, are likely to receive inappropriate or inadequate special education and related services when they are so identified.

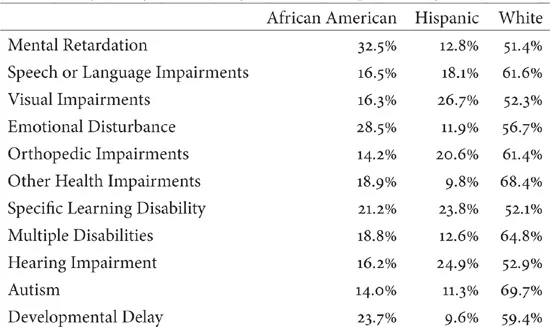

These disparities have always plagued the special education system. Table 1 reflects the current status of racial disparities in disability classification, using data available for 2010.12

As has been true since the early court cases in the 1970s, which chapter 2 will discuss, African Americans are overrepresented in the categories of mental retardation and emotional disturbance and underrepresented in the categories of autism and other health impairments (typically ADHD). In 2010, when African Americans constituted about 14 percent of the school-age population13 and 21 percent of those classified as disabled, they represented 32 percent of the students identified as mentally retarded but only about 14 percent of the students identified as autistic.

Latinos reflect a somewhat different pattern of disproportional representation. In 2010, they constituted around 22 percent of the school-age population14 and were underrepresented in the category of “developmental delay,” which is used to get children extra assistance at ages three to five before they enter kindergarten. Latinos were 9.6 percent of students identified as developmentally delayed but 23.8 percent of students who were later identified as learning disabled. Whites, who represented 55 percent of the school-age population,15 were overrepresented in the categories of autism and other health impairments but underrepresented in the category of mental retardation. They constituted 69.7 percent of students identified as autistic, 68.4 percent of students identified as other health impaired, and 51.4 percent of students identified as mentally retarded. From these numbers, one might surmise that an African American boy who “acts up” in class because he has trouble sitting still might be classified as emotionally disturbed whereas a white boy with similar characteristics would be classified as having ADHD. Similarly, a very withdrawn African American boy might be classified as being emotionally disturbed whereas an equally shy white boy might be classified as being autistic. An African American preschooler who is having trouble keeping up with age-level expectations might be classified as mentally retarded; her white counterpart is more likely to be classified as being developmentally delayed. And a Latino boy who has missed developmental milestones is unlikely to receive early intervention services as developmentally delayed because of Latinos’ underrepresentation in that category.

Table 1

Disability Classification Data from the U.S. Department of Education

This point about overrepresentation by race in certain categories is different from a point about overrepresentation by race in the general category of disability. Even if poverty is linked to higher rates of disability, that higher rate of disability should not be found in some but not all disability categories. Why are mental retardation and emotional disturbance “black” categories and why is autism a “white” category? As Tom Parrish asks, “Can Connecticut, Mississippi, North Carolina, Nebraska, and South Carolina be in compliance with special education and civil rights law when black students are over four times more likely than white students to be designated as mentally retarded?”16

To answer this question, one must also understand the services connected to these disability categories. After all, the point of the special education system is not to classify children merely for the sake of classification. The point is to classify children so that an appropriate discussion can take place about the kinds of services that should be provided for that child. The IDEA is about services, not classifications.

Parrish connects classification to services and argues that the overidentification of African Americans as mentally retarded i...