![]()

1

Sordid Signs

I guess it all started the day I quit.

In December 2001, I resigned from a position as a tenured professor at a large Arizona university, and settled back in to my old stomping grounds of Fort Worth, Texas. I knew that, at best, this move would leave me a gap of eight months or so until I might or might not locate the next academic position in the fall of 2002. This gap in turn meant that, in the meantime, my only guaranteed income would be whatever few—and I do mean few—royalties might trickle in from my books. But it also meant that I had an eight-month period for unfettered field research—if only I could figure out a way to survive economically while doing it. Given my long-standing personal and scholarly interest in the often illicit worlds of scrounging, recycling, and secondhand living, the answer seemed obvious, if risky: I’d try to survive as a Dumpster diver and trash picker.1 I’d try to adopt a way of life that was at the same time field research and free-form survival.

So early in 2002 I rigged an old fifteen-dollar black-and-white Schwinn bicycle with a secondhand front basket and some extra bungee cords for the back deck, and set out mostly on this bike, other times on foot, to see what I could find. With very few exceptions, all my subsequent scrounging was undertaken in these two-wheel or two-footed modes; as an avid bicyclist, I’m not much for the destructive ecological politics of the automobile in the first place, and besides, my guess was that the value of whatever materials I could scrounge would hardly balance against the unrelenting cost of running a car.2 In fact, as the months of scrounging rolled on, and this old bicycle gradually fell apart, I replaced it not with an automobile but with another bicycle, an old one-speed BMX model I scrounged from behind a Dumpster and repaired with scrounged bicycle parts. This approach to personal transportation seemed appropriate to the worlds of both scrounging and bicycles, by the way. After all, the first modern mountain bike emerged from the doit-yourself scrounging of legendary bicycle designer Gary Fisher, who in 1974 “blacksmithed the now famous klunker from scavenged objects.”3

I’m not much for shopping, either, and so, taking my natural proclivities up a notch, I all but boycotted retail establishments during these months, instead relying as much as possible on what I could scrounge for my daily needs. As I found, and as I’ll explain in subsequent chapters, urban scrounging did in fact provide me all that I needed for daily survival, with the exception of some food items—and these could likely have been scrounged as well, had I cared to make that my focus. In fact, my scrounging yielded so much material wealth that I sent much of it on to friends, homeless shelters, food banks, and charitable organizations. Patrolling the neighborhoods of central Fort Worth, sorting through trash piles, exploring Dumpsters, scanning the streets and the gutters for items lost or discarded, I gathered the city’s degraded bounty, then returned home to sort and catalog the take. These urban neighborhoods in turn provided a wonderfully varied setting for my work and my research; within an easy bike ride of my house are old industrial areas, rail yards, million-dollar mansions, working-class neighborhoods, middle-class suburbs, little commercial clusters, and the large downtown business district. The scrounger’s world, I found, offers many a spatial permutation.

Mention of “my house” suggests an important qualification that shaped this undertaking. During these months I did indeed have a very modest home, and a partner working some thirty-five hours a week at the generous corporate wage of $9.50 an hour—and while neither of these factors would exactly qualify either of us for middle-class approval, both certainly disqualify me from any claim of somehow and suddenly becoming for these eight months a destitute soul dependent entirely on my own scrounging. The point of the endeavor was neither to pretend nor imagine that I was a homeless Dumpster diver, anyway, but rather to explore and embrace the rhythms of urban scrounging as best I could. And besides, as I soon discovered, and as the following chapters document, not every urban scrounger is without a home; many have a little house, maybe even a partner toiling away for a small hourly wage.

Scrounging the city each day, learning to live off what I scavenged, I drifted into a world that I came to call the empire of scrounge—a far-flung, mostly urban underground populated by just such people: illicit Dumpster divers, homeless trash pickers, independent scrap metal haulers, activist recyclers, alternative home builders, and outsider artists. By choice or necessity, I realized, their role within the larger social ecology is to sort among the daily accumulations of trash, to imagine ways in which objects discarded as valueless might gain some new value, and always to stay one stealthy step ahead of those official agencies of collection, sanitation, and disposal that would haul away such possibilities. By definition and by practice, the work of these illicit trash scroungers remains marginal. While the director of the city’s waste disposal department may earn a handsome living from trash, do-it-yourself urban scroungers do not; they operate at the lower economic margins, finding in the city’s trash possibilities of street survival, or other times supplements to minimum wage work. For many who spot a scrounger working a trash pile or emerging from a full Dumpster, the morality of this work is also marginal; to pick through the city’s trash is to engage all manner of unpleasant questions about cleanliness, propriety, danger, and deviant career.

This marginality is spatial as well; the spaces and situations that make up the urban scrounger’s scattered empire quite literally form the margins, define the borderlands, between the city’s social and cultural worlds. In a shared apartment house Dumpster, the leftovers of private lives coalesce into a dirty public collectivity—and if a scrounger later retrieves some of these leftovers, they may in turn become the foundation for someone else’s little home or apartment, or for another’s temporary shelter under bridge or overpass. In the back alley trash bins of commerce, the item that was yesterday a valuable and marketable commodity today transmogrifies into devalued trash, and often a free-for-the-taking treasure; in the commercial alley, the bright front stage of the shop or shopping mall gives way to a backstage of cigarette breaks, trash piles, and uncertain access. At residential curbside trash piles, the homeowner’s property line borders and invites the life of the street, the homeowner’s discards turning from private trash to public disposal problem, or for others a public resource.4 And at all of these social and spatial margins, legal boundaries are likewise negotiated, with Dumpsters and trash piles offering daily situations for deciding between private property and public access, for distinguishing scavenging from theft, if only provisionally.

Day after day in the empire of scrounge, I discovered, yours becomes mine and mine yours—but haltingly, imperfectly, ambiguously, as part of the city’s complex everyday rhythms. In this cast-off material empire the immediacy of individual consumption becomes an ongoing urban aftermath, a collective dynamic interwoven with the city’s daily life. A half-century ago, Donald Cressey wrote of the illicit ambiguities inherent in the process of acquiring “other people’s money.”5 In the empire of scrounge, I realized, the issue isn’t so much other people’s money; it’s other people’s stuff, and what to do with it when they throw it away.

Jeff Ferrell in his scrap-filled shed, Fort Worth, Texas, October 2004.

Standing in the Shadows

Along with learning what to do with other people’s discarded possessions, and how to survive from them, I looked to make some particular discoveries. As a start, I wanted to record with some precision the content of the empire’s trash piles and Dumpsters, or at least those of them that I happened upon. As one person aboard an old bicycle, I made no effort to “survey” the trash of my Fort Worth neighborhoods, much less the city as a whole. Instead, I attempted to create a close ethnography of objects lost and found by carefully recording and describing the items that I scrounged and hauled home. This detailed accounting of my take as a scrounger became the basis for a second focus as well: exploring the personal and political economy of scrounging as a means of survival. In everyday debates over homelessness or unemployment, in larger debates over an economy that increasingly produces impoverishment for most of its participants, many an assumption is made about the resources available to the homeless person, to the destitute trash picker or itinerate Dumpster diver. But what exactly is out there to be dived into or picked up? What is its value, and to whom? And just how do you cash it in?

The social situations that define the empire interested me as well. Riding an old bicycle, dressed in scrounged clothes often made filthy by the nature of my work, I sought to put myself as best I could into the situations encountered by the everyday urban scrounger, and there to observe and record the interactions that emerged. As the months and the miles rolled by, these situations and interactions began to accumulate; countless encounters with homeowners, apartment residents, police officers, homeless folks, and other scroungers of all sorts begin to suggest something of the values, perceptions, and identities circulating in the empire of scrounge. As the following chapters document, the situations and interactions that emerge inside the empire certainly reflect larger fault lines of social inequality, embody everyday dramas of life and death, offer even moments of poignant irony and good humor—but often do so in ways one outside these situations wouldn’t predict.

The steady accumulation of objects and interactions also began to address what was perhaps the broadest agenda I brought to the research. It’s long been my sense that, more than any other engine, corporate hyperconsumption drives contemporary U.S. society, along the way constructing a seductive if sad sort of storebought commonality among many of its members. As disturbing, the profligate waste produced by this endless hyperconsumptive panic seems less an unfortunate by-product than a component essential to its continuation. Worse yet, this wasteful dynamic appears to be picking up pace, both within the United States and across the borders of world culture and economy. The Worldwatch Institute has calculated that, by 2004, the world’s “consumer class” had grown to 1.7 billion people—more than a quarter of the world’s population—with almost half of this consumer class now emerging in the “developing” world. Seeing in these numbers “a world being transformed by a consumption revolution,” the institute documented a parallel intensification of general wastefulness and specific material waste, and with it increasing environmental degradation in terms of natural resource extraction, waste disposal, and shrinking natural habitats.6 While “Americans remain the world’s waste champions,” their spreading habits of hyperconsumptive waste now seem to herald material accumulation and environmental destruction on a scale as yet unimagined.7

This critique of a proliferating consumer culture—a critique at once political, economic, and environmental—has of course been made eloquently by others, not to mention put into vivid practice by many in the antiglobalization movement.8 Yet here in these months of scrounging, it seemed to me, was a chance to frame the critique differently, not in terms of comparative political economy, but intimately, sensually, filthily, from the bottom up, from inside the guts of engorged Dumpsters and from atop the towering trash piles of the world’s champion consumer society. Here, it seemed, was an opportunity to develop a critical, grounded understanding of contemporary consumption and its relation to collective wastefulness—since damn near every urban alley, every urban Dumpster, offered evidence of one as well as the other. And it was just this material evidence, I hoped, that would focus and define my general sense that contemporary consumer society was, with each new trash heap it spawned, broadcasting the seeds of its own environmental and cultural destruction. Talking broadly of an economically and environmentally unsustainable social order; demonstrating through comparative data that Western societies have perpetually wasted what others could only want, and that these others are now themselves coming to want and waste more; confronting this destructive world dynamic with carnivals of resistance outside the grand hotels of World Trade Organization (WTO) delegates and World Bank members—all constitute critically important efforts at undoing the damage. Looking for this same damage in the Dumpsters of retail stores and the trash cans of the affluent, carefully accumulating evidence of it item by discarded item, I hoped to do my part as well.9

In this I also hoped to do my job as a criminologist. By studying the dynamics of crime and law—that is, the dynamic by which certain activities come to be outlawed and legally suppressed on the basis of their supposed social harm, while other activities come to be protected, even encouraged, by the law—criminologists put themselves, inevitably, in the middle of larger debates over morality, decency, justice, and the social good. In this light, a certain irony emerges: despite their academic designation, criminologists cannot do their job well if they confine themselves to the study of “crime,” since the crimes of one historical moment are often not the crimes of the next. Instead, they must study ongoing processes of criminalization and legalization, exploring in their research the slippery boundaries between law and morality, crime and victimization, legal regulation and political repression—and presenting in their analysis of these processes their own critical judgments about social benefit and social harm. My own intellectual agenda and preexisting if provisional judgment—that consumption and waste present one of contemporary society’s most destructive dynamics—pushed me to investigate this dynamic as a matter of social and criminological concern, and to explore within it the shifting, ambiguous legalities of waste and waste pickers. In turn, my investigation raised a troubling question to which I’ll return more than once in the following chapters: Is the criminologist’s job to resolve legal and cultural ambiguities, simply to acknowledge them—or sometimes even to celebrate them?

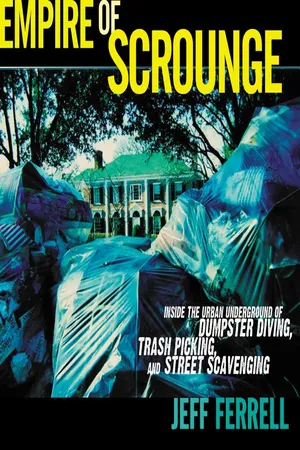

The trash heap of a River Crest McMansion, Fort Worth, Texas, April 2004.

Within the empire of scrounge, I discovered, the boundaries of law and crime have indeed shifted more than once, and are shifting again today; even the word that others and I use as shorthand for this world embodies long-standing historical uncertainty, and ongoing ambiguities of marginality and illegality. The verb “to scrounge” evolved over the past century or so as a variant on the dialectal formation “to scrunge,” meaning “to steal,” or more vaguely “to search stealthily, rummage, pilfer.”10 Interestingly, the term—and the practice—have taken on special currency during the moral and legal disruptions of wartime, when soldiers and others have been forced to negotiate the ambiguities of an anomic world. In this context, the Oxford English Dictionary offers a variety of legally blurry definitions for scrounging—“To sponge on or live at the expense of others. To seek to obtain by irregular means, as by stealth or begging; to hunt about or rummage… . To appropriate… . To ‘pinch’ or ‘cadge’”—and includes some equally ambiguous examples of popular usage. “Scrounging for wire is legitimized by the War Office,” reads one missive from World War I, dated 1918—yet a year later another notes “complaints about ‘scrounging,’ which are nothing but outbreaks of loss of moral judgment.”

By the next world war—during which U.S. citizens were encouraged to scrounge scrap metal and other discards as part of governmentorganized reclamation campaigns—the situation was nonetheless no more certain. According to one 1939 report, “the Southern Railway gave a staggering figure for the specially dimmed bulbs which had been stolen (I beg pardon, scrounged) from their carriages in the first weeks of the war”; at war’s end, another report pointedly noted “that ‘pilfering’ by a native is indistinguishable from ‘scrounging’ by an American soldier, and that ‘chiseling’ and resale of Pos...