![]()

1

Mike Nichols

1931

FOR NEARLY HALF a century, Mike Nichols has been one of America’s most creative and influential artists. He is among the tiny group of people to have won all four of our most competitive awards for film, television, theater, and sound recordings—an Oscar, an Emmy, a Tony, and a Grammy.

Mike first gained notice in the early 1960s as half of the legendary comedy duo Nichols and May, skewering this country’s middle-class social mores. He went on to become an ever more complex and nuanced artist, a leading film and theater writer and director who has spent four decades exploring and exploding the most deeply held American values. His first film, The Graduate, defined the zeitgeist of the sixties. But my guess is that few of that film’s millions of fans could possibly imagine that its director’s brilliant take on generational change as a metaphor for larger changes abroad in our society was the insight of a man who grew up in an era of total chaos, barely surviving one of history’s worst atrocities, the Jewish Holocaust in Nazi Germany.

I approached Mike as soon as I conceived of this project. I wanted to include him because, over dinners on Martha’s Vineyard, I had come to learn a bit about his remarkable childhood. I also wanted us to try to investigate the ancestry of a person who was of both German and Russian Jewish ancestry, the latter of which presents formidable challenges to genealogists. I was pleased at how far back we could trace his family on both of these lines. But just as I enjoyed finding that the imagination, careful preparation, and deep intelligence that have characterized his career are actually part of a family tradition stretching back at least four generations, I was dismayed to learn of terrible atrocities committed against several of his ancestors. Members of Mike Nichols’s family have suffered a remarkable amount of political persecution from the Left and from the Right, ranging from the czars in Russia in the nineteenth century through the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 and the German Revolution a year later, to Stalin’s purges in the 1930s and Hitler’s insane persecution of the Jews. We found relatives on both sides of Mike’s family who faced terrible injustice, suffering, and even execution—yet somehow passed on to their descendants the talent, optimism, and inner strength needed to persevere.

Mike’s direct ancestors also seem to have had an uncanny knack for migrating one step ahead of great historical events. His father’s family left Russia in 1917, on the eve of the Bolshevik Revolution, eventually settling in Germany. His parents then found themselves forced to flee the Nazis shortly before it became impossible for Jews to leave the country. He has many ancestors who were not so lucky—and who died in these historical cataclysms.

Much of Mike’s work, and many of his most memorable characters, have the feeling of the outsider observing people and events from afar, from almost a peripheral vantage point. As we sat down to begin our interview, I asked him if he thought his style was unique among his contemporaries in that way. His answer—modest but clearly thought out—was telling: “I don’t think I’m so unique,” he replied. “But I’m a Russian German Jew—and I think I do have a refugee sensibility. I think the reason I say ‘refugee’ rather than just ‘traveler’ is that if you are a refugee, there’s urgency. You need to be hearing and noting how people are doing things—the local customs. And doing that means studying nuances of behavior. I’m very aware that all the time I was growing up, I had that awareness of behavior, of how they do it here. And I was always honing my sense of observation, searching for invisible signs of good things, bad things, anger, pleasure, affection, dislike, the thing you always got an ear cocked for—will it be okay? Those things get sharpened, you know, because it went pretty uniformly badly as I was storing them up.” In other words, the subtle manner by which he evokes characters’ personalities through the nuances of their behavior and attention to minute detail can possibly be traced to the survival skills he developed as a refugee, even—or especially—as a child.

Mike was born Michael Igor Peschkowsky on November 6, 1931, in Berlin, the oldest child of Brigitte Landauer and Dr. Paul Peschkowsky, a physician. He spent his first seven years as a very sensitive and clever child in an upper-middle-class Jewish family, largely unaware of the dangers his family faced after the Nazis came to power in 1933. By 1938, however, their perilousness was becoming clear. Across the country, Jews were being arrested and sent to concentration camps, synagogues were being burned, and Jewish businesses were being seized. Mike remembers his parents spending what he describes as an endless amount of time waiting at consulates, trying to get papers to leave the country. Most of the people who were on those lines with them ended up perishing in the Holocaust.

Mike Nichols as a baby in Berlin, with his parents, Brigitte Landauer and Paul Peschkowsky. (Used by permission of the Nichols family)

The Peschkowskys succeeded, as luck would have it, because of Nazi Germany’s infamous nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union, the cynical, short-lived agreement between two of the twentieth century’s most brutal regimes. “The only reason we were able to leave was the Stalin-Hitler pact,” Mike said with an ironic smile. “During that time, Jews with Russian papers could leave Germany. Nobody else could. And a patient of my father’s—at least this is the legend in the family—a patient of my father came to his office and said, ‘They’re taking doctors alphabetically, and your initial comes up next month. Get out.’ So he did.”

We could find no evidence documenting this family legend, though many stories of its kind are true. But we did find shipping records that showed that Michael’s father arrived in New York on August 14, 1938. He quickly passed his medical boards, set up a practice, and sent for his family. Mike’s mother, however, was ill and could not travel. Fearing the worst, she sent her two boys off alone on April 28, 1939—and then, just as miraculously as her husband’s escape, managed to join them the following year.

I showed Mike the manifest of the SS Bremen, the ship that left Germany for America carrying seven-year-old Michael Igor Peschkowsky and his three-year-old brother, Robert. “It’s very startling,” Mike said, looking at this document for the first time and recalling vivid memories of that trip he made more than sixty years ago. “I remember everything about getting on the boat,” he said. “We were at the gangplank and about to go down when a Hitler speech began. And, of course, you didn’t listen to it on the radio; you listened on loudspeakers on every block, and while Hitler spoke, nothing moved. So they held us back from the gangplank. And I remember mother wanted to give us supplies, and they were all saying, ‘Sorry, madam, there’s nothing we can do. Nothing happens till the speech is over.’ I remember that.”

“And then when we were on the boat, we had little purses on cords under our shirts, and they had fifteen [German] marks in them for emergencies. And I knew two sentences in English: ‘I don’t speak English’ and ‘Please don’t kiss me.’ Because we were alone. And I think if you’re a kid without adults, people tend to kiss you, because what do you do with a kid, right? So I remember that. And I remember my brother and I got very excited because we’d never had food before that made noise. But Rice Krispies! We were thrilled with Rice Krispies and excited about Coke which—shhhhh—you could hear, and it tasted great. We went nuts for that stuff.”

This story fascinates me because it is charmingly revealing about the different ways in which people see—in this case, a child’s perspective on even the most traumatic historical events. Mike and his brother were children traveling alone during one of the most dangerous moments in history, fleeing people who wanted to kill them. And what do they most vividly remember? Rice Krispies and Coca-Cola.

“We were basically unaware of what was really happening,” he continued. “I do have a specific memory, though, of coming down the gangplank and seeing my father waiting. We’re hugging and talking, and across from the dock there’s a delicatessen, and it had a neon sign with Hebrew letters. And I said, ‘Is that allowed?’ And he said, ‘It is, here.’ So that was the first thing that happened to me in New York, so I must have known something.”

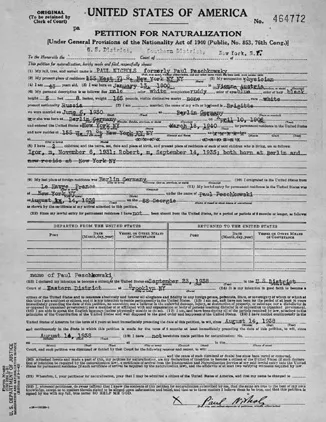

We found a surprising number of documents illuminating Mike’s family’s journey to America. They tell a story that was common in its time but that most Americans today can’t quite imagine. Dr. Paul Peschkowsky arrived in the port of New York on August 14, 1938, and signed a declaration of intent to become an American citizen, something he’d have to wait five years to achieve. His declaration says that he was a physician, that he had sailed from France, and that his race was “Hebrew” and his nationality Russian. Shortly after arriving, he changed his last name to Nichols, signing his petition for naturalization “Paul Nichols, formerly Paul Peschkowsky.”

When Mike and his brother arrived in New York, they took their father’s new name. In yet another telling sign of just how young and innocent he was, or perhaps how deeply traumatic this was, Mike has absolutely no memory of his family’s changing his surname, a hallmark, after all, of one’s identity: “I don’t remember Peschkowsky,” he told me with a shrug. “I only start remembering Mike Nichols. Nichols was everything. We were Nichols.” But that name change was not without its consequences.

Mike soon learned that Nichols was not a common name among American Jews, instead being prevalent among Protestants. “I became aware that it was not a name that told people easily that you were Jewish, like Goldschmidt or any thousands of names,” he told me. “And this was not something I wanted.” Where did the name Nichols come from? Mike told me that he believes his father chose it because in the Russian style of naming it was a variant of his patronymic, which he had inherited from his own father (whose birth name was Pavel Nikolaevich Peschkowsky). “My father thought Nichols was perfectly reasonable,” Mike said, laughing. “He didn’t know that it was a goy name. He just took his father’s patronymic, unfortunately making me Michael Nichols—which was not my favorite.”

Setting aside his own feelings on the matter, Mike told me that his father was genuinely thrilled to become an American. “He adored America,” Mike said, smiling warmly. “And he always did very well. He was an extremely good doctor, and he had very fancy patients. He had [Vladimir] Horowitz. He had Sol Yurick. He was the doctor to Russian stars. And he was very good at the dinner table. He told great stories. He was full of life. I still remember his happiness at buying a Packard Clipper. I remember that car with emotion, because he loved it so much and it was so beautiful—black, with a leather interior.”

Naturalization petition signed by Mike’s father, Paul Nichols. This document indicates that Paul changed the family surname from Peschkowsky to Nichols soon after arriving in America. (Public domain)

But Paul Nichols did not get to enjoy his new freedom or his new country for very long. Having successfully fled Nazi Germany, he died of cancer at age forty-four. Mike remains angered by his loss, which he believes could have been prevented. “The first job my father got as a doctor in New York,” Mike said, “was working for a union on 42nd Street, running the x-ray machine for the union members. And unbelievably, nobody knew about shielding from x-rays. And he got leukemia. It was an occupational death, no doubt. It’s hard to imagine that they didn’t know, what with Madame Curie dying of radiation and so forth. He was a baby. And I—selfishly—still needed him.”

When his father died, Mike’s life was turned upside down. The loss of a parent proved far more profoundly disruptive than moving to a new continent or adopting a new culture had. And even though his father loved America, Mike was not so sure how he felt, even as he adapted to his new surroundings. “I lost my accent in two weeks,” he said. “I remember being on the school bus and saying, ‘What means emergency?’ And two weeks later there was no problem anymore. That’s what kids can do. But I was not happy.”

Despite the fact that he spent the first seven years of his life growing up Jewish in Nazi Germany, Mike told me that he never experienced overt anti-Semitism until he came to America. “In Berlin,” he said, “I went to a special school for Jews, but I didn’t know that was unusual. And once some guys with a swastika on their armbands took my bike in the street. But that was about it. And I don’t even remember it as a big deal. I just thought, ‘Well, easy come, easy go.’” His parents, he said, sheltered him from what was going on around him. But as he grew up in New York in the forties, the prevalence of casual anti-Semitism shattered his innocence about other people’s attitudes toward his religious and cultural heritage.

“I remember I went to PS 87 for a year or less,” he said, “and for the first time somebody said something about me being a Jewish kid. It was one of the teachers, and it wasn’t in a particularly friendly tone. So I came home a little concerned about it, and my mother was great. She put an arm around me as we were sitting on the sofa, and she told me about Jews and what it meant to be a Jew and what the problems were. And none of this had ever been spoken of before, or she wouldn’t have had to have this little talk.”

It says quite a lot about the sheltering effects of nurturing families, and the particularity of prejudices, that Mike’s experiences as a child in Nazi Germany so little prepared him for anti-Semitism in America. “I didn’t think of it as terrible,” he says. “I just wondered what she meant. I just had no frame of reference. Because Jews in Germany, before all this, were Germans. They didn’t speak Yiddish. They didn’t celebrate Jewish holidays. My grandfather, who was in the end a Zionist, spoke not a word of Yiddish, much less Hebrew. All this came to the surface later. I think it was always underneath, as it has been for Jews always everywhere. But I learned little by little.”

With his father’s death, Mike’s problems grew. “I was not happy with myself,” he said, “and I was not happy at home. My father was gone, my mother was deeply miserable—as anybody would be whose husband died. She didn’t know the language; she had never been alone in her life. And yet from that point, she got it done. She took good care of us. But I never felt pleasure in being with people and being in any situation, really, until I went to the University of Chicago. In line to register, I started to talk to the girl in front of me, a beautiful girl—Susan Sontag. That was the first person I met, and from that point on, because I was at the University of Chicago, I have this shocking experience over and over: ‘Oh my god, they’re like me. I’m like them. Oh, they’re weirdos.’ For the first time in my life.”

Double consciousness is the capacity to perform a function and watch yourself performing that function at the same time. I believe that all brilliant artists have the capacity to watch themselves watching others. This talent describes Mike Nichols’s outsider perspective in a nutshell. Can we trace this capacity with certainty to any one set of experiences? Of course not. Mike Nichols’s genius would have manifested itself in one form or another no matter where he may have been raised. But those poignant experiences of exile, alienation, studied adjustment, and redefinition, I’m convinced, have been leitmotifs throughout his remarkable body of work—if not its driving force.

I wondered if this gift for what we might think of as social introspection could be found elsewhere on his family tree. We unearthed a number of stories suggesting that Mike comes from a long line of outsiders and mavericks. But finding these stories was not easy, especially along Mike’s paternal ancestry, which stretches back to Russia. Locating records of Russian Jews is among the most difficult challenges in genealogical research. A genealogist once told me that finding the ancestors of Russian Jews is at least as difficult as tracing the slave ancestors of African Americans. For centuries, the forebears of men and women like Paul Peschkowsky were barred from citizenship and its rights. They were confined to Jewish settlements that were subsequently destroyed either by Stalin or by the Nazis in World War II. They did not even have surnames, other than patronymics (“son of” names). In other words, they lived lives without a paper trail, lives almost totally unrecorded. Jews appear in Russian documents only beginning in the nineteenth century, when the czar, seeking to tax them and conscript them, required that they adopt last names.

We began our search by consulting Mike’s father’s death certificate, which is filled with information given by his wife, Brigitte. From it, we learned that Paul Peschkowsky was born to Russian émigrés in Vienna, Austria, on January 13, 1900, and that his mother’s name was Anna Distler. His father is listed as “Nicholas Nichols”—but, as we have seen, this was not his real name. Mike’s father was originally named Peschkowsky; in Vienna, we were able to locate his birth record, bearing the name “Nosson Peschkowsky.” This record says that Nosson (the Yiddish form of Nathan) came to Vienna from Tomsk, Siberia, where he was born in 1870. We found other records in which Nosson went by the name of Nikolai, probably because it was the closest Russian equivalent. So the fluidity of naming started early in Mike’s family, and it involved at least two languages. We also found a wealth of records suggesting that Mike’s grandparents traveled frequently between the luxurious European capital of Vienna and the rough hinterlands of Siberia throughout the first decades of the twentieth century.

By this point, Mike and I were both fairly confused. We wanted to know how—and why—his grandparents were traveling so much. Given the state of Russian records, the prospect of unraveling this mystery looked bleak at first. But then we got very lucky: We found the city directory of Irkutsk, one of the largest cities in Siberia. It lists Mike’s grandfather, “Dr. D. N. Peschkowsky,” as a specialist in venereal disease. We also learned that he was a member of the East Siberia Physicians Society and that his wife, Anna Distler, Mike’s grandmother, was a member of the board of the Irkutsk Charitable Society for the Assistance of Poor Jews. They seem to have been very prominent people in Irkutsk. And the source of their status appears to have been the family of Mike’s grandmother, the Distlers.

Mike had heard many stories about this line of his family and was eager to learn more. “I’ll tell you right now all I know about my grandmother Anna,” he said. “And I know it only from the wife of my now deceased Russian cousin. The story is that when my grandmother left Russia in the 1917, she took with her forty pieces of luggage. And in the forty pieces of luggage were fifty gold bars from the family goldmine. But I have no idea if that’s true.”

The Distler family in Russia. Grigory Distler, Mike’s great-grandfather, is in the middle. Mike’s father, Paul Peschkowsky, is the young boy on the far right. (Used by permission of the Nichols family)

He then showed me a remarkable photograph of the handsome Distler clan taken sometime in the late nineteenth century, looking almost like an imitation of a period photograph. “My cousin gave me this,” he said. “It’s like that picture you take o...