![]()

1

The Latino Crime Threat

A Century of Race, Marginality, and Public Policy in Los Angeles

Early in the morning of September 22, 2009, I went online to read the Los Angeles Times. I was struck by a headlines of a major, developing story: “Massive Police Raid Targets Brutal L.A. Gang.” The subheading mentioned the Avenues gang, which the mayor and police chief two years previously had targeted in an “aggressive suppression strategy” against the city’s eleven “most violent gangs”; this was the same gang that had earlier been connected to a case of a murdered Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy. I immediately felt tense and worried.

The previous week, Matthew, a twenty-year-old member of Homeboy Industries, and of the Avenues gang, had asked me if I knew of any vocational programs that could lead to stable employment. He said he had recently called a well-known vocational school, but that they were reluctant to answer his questions after they found out he had two felonies on his record. As I scoured the article for details, I feared that Matthew had been picked up in the gang sweep. The Los Times provided gripping photos of twelve hundred law enforcement officials and federal agents, armored with assault rifles and military-style vehicles, taking in these Latino men in the predawn hours. I scanned through photos of men who looked like Matthew—adult Latinos with shaved heads and white T-shirts, sitting on curbs with their hands cuffed behind their backs or stretched out on police cars as they were searched. The images looked like something out of the Iraq War. They were meant to send a clear message: we should fear urban gang members, and it is law enforcement that is protecting us from them.

I rushed to Homeboy Industries to collect details about the raid and find out if Matthew had been taken in. As I saw the chair where he normally sat occupied by someone else, a sinking feeling overtook me. The next day, I spoke with Matthew’s supervisor, Valerie, a Latina with a college degree and very professional demeanor, who told me in a concerned tone that he had been arrested in the sweep. The FBI was working hard to build a case against the Avenues, drawing charges against the gang based on the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act. However, the FBI wiretaps linking Matthew to his gang were four to five years old, and predated his entrance into Homeboy Industries. Matthew was not involved in the death of the murdered deputy, but, according to Valerie, he was threatened with a life sentence and offered a plea bargain of ten years in prison for having carried a gun during drug deals several years ago. I was crushed, thinking of the excessive severity of the sentencing laws that he faced. The next day was the anniversary of President George W. Bush’s nationally televised address on the greatest financial crisis since the Great Depression, and I couldn’t help but think of the corporate executives that escaped prosecution for the events that led to the Great Recession. Matthew was released after Homeboy Industries staff members gave character testimony on his behalf in court, but he nonetheless lost three years waiting behind bars.

In his critical analysis of post-Depression American crime policies, law professor and sociologist John Hagan (2010) has argued that, following the 1970s, America’s prevailing concerns with safety shifted from the international to the domestic realm. This played out through two shifts in crime policy: a realignment of law enforcement’s focus from white-collar crime (i.e., “suite crime”) to drug, property, and violent crimes (i.e., “street crime”), as well as through a shift in responsibility of prosecution from local and state governments to the federal government. In the “Age of Roosevelt” (1933–1973), politicians, policy makers, and academics focused on structural factors linked to crime, introducing solutions based on concepts of social reform (Hagan 2010, 67). However, President Ronald Reagan and other influential politicians subsequently shifted the focus away from social reforms and toward incarceration. They skillfully enflamed popular fear of crime with the myth of the career criminal, supposedly emboldened by society’s weak punishments for violent crime. This shift led to increasingly severe sentencing for street crimes, exacerbating punishment for those perceived to be career criminals in the interest of national security.

As I read the Los Angeles Times article on the Avenues sweep, which mentioned law enforcement officials’ intentions to prosecute gang members under the RICO Act, it certainly seemed to me as if not only the paper’s imagery, but our federal policies and priorities were focused on sending a message that, as a nation, we should fear urban gang members. Remarks from an interview with an arresting gang officer scorned gang members who tried to reform but failed, implying that they were indeed career criminals and had to be imprisoned. Most notably, although the story did not mention nationality or class, those became the salient topics raised by angry readers online. As I scrolled down the page, through the dozens of comments laden with racist messages targeting Latinos, the most prominent theme seemed to be a concern with undocumented immigration (e.g., “Illegal immigration is the root of most gang problems here in CA”).

Accompanied on occasion by virulently racist outbursts, several Times readers proposed racially oppressive tactics to address the problem of crime, including the following:

• Deportation (e.g., “Boot them out of the country”)

• Militarization of the streets (e.g., “Reroute the 10,000 troops that are scheduled to go to Afghanistan”)

• Militarization of the border (e.g., “[C]lose the border”)

• Tougher sentences (e.g., “Only life sentences and the death penalty will cure the gang cancer destroying our country”)

Shockingly, a few even advocated for sterilization of immigrants (e.g., “If you castrate them, then they won’t be able to have kids that will grow up to be just like their parents”).

Not every commentator shared those xenophobic tendencies. However, anthropologist Leo Chavez, in his analysis of media coverage of Latino immigration, suggested that mainstream news reports often provide sufficient commentary and imagery to facilitate sustained anti-immigration rhetoric. Racist, anti-Latino discourse creates a “Latino threat narrative” that centers on the themes of “invasion,” “reconquest,” and “separatism” (Chavez 2008, 29). It is this volume’s contention that anti-Latino discourse concerned with gangs, crime, and national security is a crime-focused variation of the Latino threat narrative, what is termed the Latino crime threat in the introduction. The Los Angeles Times’ coverage of the Avenue sweeps fostered development of the Latino crime threat by providing images of the militarized raid, as well as an online comment board on which readers could interpret those images. Restrictive crime policy and the Latino crime threat have developed in tandem; local law enforcement agencies have adopted oppressive policing tactics that draw from—as well as build on—misinformed stereotypes of urban street gangs as violent and organized (Klein 1995).

Sociologists and critical criminologists place post-1970s economic decline in advanced industrial nations at the core of their analysis of racism, marginality, and crime control (Bauman 2004; Wacquant 2009[1999]; Young 2011). The contemporary hegemonic project of the “security state” manages “the risks posed by social disintegration” by exercising social control through crime control, and by criminalizing social policy (Hallsworth and Lea 2011, 142–144). However, although they have noted the rise of mass incarceration and state surveillance targeting immigrants and persons of color, critical sociologists have failed to conceptualize race as an unstable category, socially constructed through political struggle. How did the late-twentieth-century tide of rising incarceration sweep across racial lines? How did Latinos remain marginalized, vulnerable to the state’s surveillance, while earlier cohorts of Southern and Eastern European immigrants seemingly assimilated into the mythical “melting pot”?” Although European immigrants escaped the issues of immigrant poverty, marginality, and crime, these issues have now become much more acute among blacks and Latinos.

The early-twentieth-century Chicago School of sociology sought to combat the racist eugenics movement, which asserted that Southern and Eastern European immigrants’ involvement in poverty and crime was a function of biology (e.g., Park, Burgess, and McKenzie 1925; Thrasher 1927; Whyte 1943). Building on the use of language from the hard sciences, the Chicago School instead emphasized that social ecology—structural factors such as urban development or social marginality—was the basis for immigrants’ higher association with crime. This line of reasoning had a profound influence in the 1930s on the development of U.S. public policy and the way in which crime was addressed. Under Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration, social policy took shape through a reformist-inspired agenda that sought to address crime by addressing its root causes: poverty and marginalization. For example, Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) attempted to ameliorate social problems by addressing the issue of substandard housing conditions. However, in the struggle for progressive social policy, Chicago School–inspired reformers articulated claims that rested on racist and sexist depictions that further marginalized Los Angeles’s Latino population.

In the post-Civil Rights Movement era, notions of black/Latino gendered pathologies, such as the “welfare queen” or the streetwise career criminal, have set the stage for the state’s retreat from social programs and simultaneous increasing surveillance over marginalized populations. Law professor Dorothy Roberts (2012) captured this in her work on black mothers’ relationship with social services, which in the years following the Civil Rights Movement has evolved from material assistance uplifting poor families to enforced surveillance and the threatened removal of black children from their families. Whereas prior to the Civil Rights Movement, racism in many places took the form of an overt “Jim Crow” regime, latter-day racism is characterized by much more subtle, “coded” form. Guided by neoliberal “blame the victim” ideologies and “race-neutral” policies that reinforce racial inequality, “colorblind racism” has emerged as the new racist hegemony of the post–Civil Rights Movement era (Bonilla-Silva 2003). Crime control, as a facet of the late modern state, has enabled racism to persist against blacks and Latinos (i.e., Gilmore 2007; Wacquant 2009[1999]; Western 2007).

The turn-of-the-century Latino crime threat—what Los Angeles Times readers viscerally responded to in the story about the Avenues sweep—evolved across a century of white racial domination and tumultuous racial conflict. The Latino crime threat was fashioned through the early-twentieth-century struggle for social reform, and was refashioned through white resistance against civil rights gains. The post-1970s rearticulation of white racial hegemony set the backdrop for modern crime control efforts, and has catapulted American racism into the twenty-first century through the post-9/11 War on Terror. It thus shortchanges our understanding of Latino urban marginality, gangs, and faith-based social programs to simply say that such processes have been shaped by restrictive crime policy. A more accurate analysis of the mass incarceration of Latinos and its undergirding logic, the Latino crime threat, accounts for the racialized and gendered nature of modernizing, state-sponsored policies and reforms.

The Myth of the Melting Pot: Race and Reform in Early-Twentieth-Century Los Angeles

Immigration and Backlash

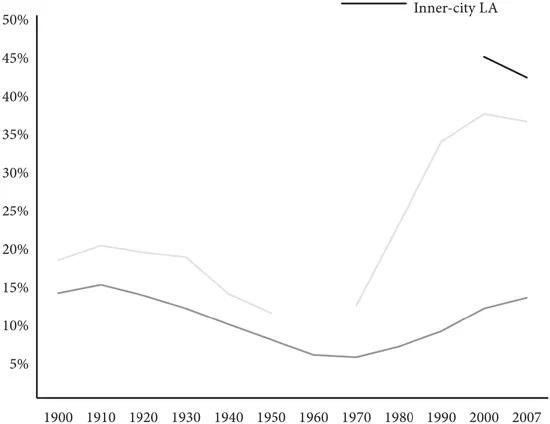

The period between 1900 and 1920 saw the greatest growth in immigration in U.S. history. Waves of Southern and Eastern European immigrants washed ashore at Ellis Island and other entry points, and fanned out across America, gravitating toward large cities such as New York and Chicago. American immigration was at its highest peak in 1910, when 14.8 percent of the U.S. population was foreign born (see figure 1.1). Los Angeles remained relatively unaffected, as statistics show that the city’s rate of foreign-born residents (19.9 percent) was only slightly higher than the national average in 1910 and during most of the century’s first immigration wave.

Since its early history, Los Angeles has been a city of both utopia and dystopia (Davis 1990). In the early twentieth century, Los Angeles’s Westside had a largely middle-class, native-born, white Protestant population. Many Angelenos were internal migrants who originally hailed from the Midwest and held socially conservative, antiunion values (Milkman 2006). City ordinances in 1909 made western Los Angeles the first exclusively residential urban area in the United States (Spalding 1992). Conversely, Los Angeles’s Eastside, especially Boyle Heights, was populated by a veritable diversity of ethnic groups: Jews, Russians, Mexicans, Japanese, Slavonians, and Chinese. Industrial development and dilapidated housing made the Eastside a destination for a large number of immigrants (Spalding 1992).

Major influxes of Russians, Jews, and Mexicans arrived in Boyle Heights at different times, but overlapping in a way that reinforced multiculturalism rather than ethnic succession. A large group of Russian Molokans, a Christian sect that had broken from the Russian Orthodox Church, migrated to Los Angeles between 1905 and 1910, and settled in Boyle Heights (Spalding 1992). “Russian Town,” located along “the Flats” on 1st Street, was the largest Molokan enclave in the United States. The Russian Flats covered a large portion of Boyle Heights: bounded on the east by Lorena Street, on the west by the Los Angeles River, on the south by Olympic Boulevard, and on the north by Mission Road (Vigil 2007).

The early twentieth century marked a period in Boyle Heights’ development when reformers managed to directly influence changes in social policies that shaped life in the neighborhood (i.e., Spalding 1992; Lewthwaite 2009). After the Los Angeles Housing Commission was established in 1907, commissioners investigated the 1st Street Flats that were home to the area’s Russian and Mexican populations (Spalding 1992). Compared to the extensive tenement districts in East Coast cities, the population density in Los Angeles was relatively low. Nonetheless, slum housing like that along 1st Street still characterized much of Boyle Heights. A 1910 report by the commission stressed overcrowding and unsanitary conditions, as well as lack of sufficient water supply, toilet facilities, and drainage (Spalding 1992). More poignantly, the report stated that “Jacob Riis, when he went through our congested districts, said that he had seen larger slums, but never any worse” (Los Angeles Municipal Housing Commission 1910, cited in Spalding 1992, 108). In the 1920s, cheaper housing drew still more immigrants, including Mexicans. It was during this period that Mexicans began to build shacks in Boyle Heights’ ravines and hollows (Gustafson, 1940, cited in Moore 1991, 11).

Figure 1.1. Percent Immigrant Population, by Year

Source: Census 1900–2000; American Community Survey 2005–2009.

Contrary to contemporary romantic perceptions of early-twentieth-century America as an inclusive “melting pot” for immigrants of European origin, many Americans responded to the rapid rise of Southern and Eastern European immigration with xenophobia. Eugenicists, who proclaimed that immigrants’ genetic propensity led to involvement in crime, pressed for the Johnson Act, which effectively closed the U.S. to Southern and Eastern European immigration after 1924 (Jacobson 1999) (see figure 1.1). The eugenic stance was countered by the Chicago School sociologists, who contended that social problems in urban immigrant communities were rooted in social disorganization (Park, Burgess, and McKenzie 1925; Thomas and Znaniecki 1918; Thrasher 1927; Young 1929). The Chicago School argued that industrialization and urbanization created unsupervised, “interstitial” areas where boys could play, but that could also lead to petty theft and introduction to the criminal underworld (e.g., Thrasher 1927, 20). Immigrants tended to reside in lower-income neighborhoods, in a “zone of transition” (Park, Burgess, and McKenzie 1925, 148), where interstitial areas were abundant and second-generation immigrant boys were especially vulnerable to delinquency.

Pauline Young (1929) extended the social disorganization perspective to Boyle Heights’ 1st Street Flats, which had pockets of marginalized poverty that yielded unsupervised territory for boys to play in. It was in this context that several Chicano gangs first emerged in Boyle Heights (Vigil 2007). Three persist as major Los Angeles gangs today: Cuatro Flats, Primera Flats, and White Fence (Vigil 2007, 40). However, oral histories archived with the Boyle Heights Historical Society (2011) have suggested that gang violence was not salient at the time. In addition, research on Chicano prisoners has suggested that, although White Fence was the first Eastside gang to start carrying guns—in the 1940s—there were no gang wars at the time (Vigil 2007). Nonetheless, anthropologist Diego Vigil has traced the roots of Los Angeles gangs to this era, suggesting that “gangs became so deeply rooted because of enduring social isolation and neglect of marginalized populations” (2007, 43).

The Paradox of Social Reform

During the 1930s, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal ushered in an era of social reform across the nation. The Wagner-Steagall Act of 1937 established the United States Housing Authority (USHA), which spurred local governments to establish their own housing authorities in order to receive funding for slum clearance and public housing. The push for social reform through housing development advanced the Chicago School perspective on immigration, poverty, social disorganization, and crime. In Los Angeles, the racialized contests over public housing were disproportionately waged on the Eastside—Boyle Heights in particular.

William Burk’s 1937 “Juvenile Delinquency and Poor Housing in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area” was among a number of surveys and reports funded by the WPA during the era (Spalding 1992, 113). Burk found that the Flats had an “extraordinary” juvenile delinquency rate of 62.8 per 1,000 juveniles and a 60 percent repeat offense rate (Spalding 1992, 113). In 1938, the City of Los Angeles created the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles (HACLA), and together with the WPA, applied for funding under the Wagner-Steagall Act (Lefthwaite 2009). HACLA hired a photographer to document the case for public housing (Spalding 1992).

As American studies scholar Stephanie Lefthwaite noted in her analysis of race and social reform among Mexicans in early-twentieth-century Los Angeles, the push for social reform deepened racial divisions and exacerbated ethnic marginalization:

A generation of reformers experimented with a variety of policies in health, housing, education, and labor: Progressive-era settlement work and housing reform; Americanization; segregation and repatriation. … Beneath these varied agendas, however, lay the patterning of racial, ethnic, and cultural differences. Reformers challenged yet supported the inequalities that circumscribed Mexican lives by pro...