![]()

1

Moving Faith

Right after high school, Pedro and Lucinda were married outside Mexico City on a hot August day in 2000. The wedding was simple, but it remained a memorable celebration for the couple’s family and friends. After the church ceremony, Pedro’s and Lucinda’s families joined together for a family portrait to commemorate this special day. But two people were noticeably missing from the photograph — Lucinda’s father and brother.1

Lucinda’s father had died several years earlier of a heart attack. Since the family’s provider was no longer living, Lucinda’s brother, Juan, had moved to the United States, where he could make much more money to support his mother and four younger sisters. Before Juan had left for the United States, he had worked at a local painting company. Juan and his coworker Pedro had spent many days and nights painting houses and large warehouses, and Juan had grown to trust and respect Pedro very much. So he had had no hesitation in introducing him to Lucinda. Juan had hoped the pair would date and Pedro could become, at least temporarily, el hombre de la casa (the man of the house). As Juan had planned, Pedro and Lucinda fell in love and began to plan their wedding. And to Juan’s contentment, Pedro stuck around the house to help the family run necessary errands and be there for Lucinda’s mamá.

While living in Lucinda’s house, Pedro — a self-proclaimed agnostic — became acquainted with the Catholic Church. He didn’t really enjoy going to church, but he went to mass to appease Lucinda’s mother. But when their engagement was announced, Lucinda insisted on a church wedding. There was a small problem — Pedro needed to be baptized before he could be married in the church. So at the age of nineteen, Pedro joined a catechism class of twelve- to thirteen-year-olds to learn the doctrines and teachings of the Catholic Church. A few months after his baptism, Lucinda and Pedro were married.

While dating, Pedro and Lucinda discussed their dreams for their children. Lucinda heard about job opportunities from her brother and other family members in New Jersey. It sounded like a wonderful place where jobs were plentiful and life was much easier than in Mexico. Pedro and Lucinda knew that staying in Mexico City was not very promising for their future children. They also knew they could make a lot more money in the United States.

So Pedro and Lucinda, even before they were married, made the decision to go north, cross the border, and start new lives in New Jersey. As they made preparations, Lucinda grew anxious. She knew it would not be an easy journey. For support, she convinced her sister Maria to go along. With the financial help of Lucinda’s brother in New Jersey, the family scrimped and saved the six thousand dollars they needed to hire a coyote (border guide) to help them cross the border. They left in October before the winter settled in.

Hiring a coyote is no guarantee of a safe passage. All three knew the risk of crossing an increasingly militarized border. What if they were to run out of food or water? What if they were robbed? Or, worse yet, what if someone tried to kidnap or shoot them? Despite the risks, the promise of a better life — and more importantly a better life for their future family — was worth it. After many hours on several buses, they arrived in Tijuana, just south of the U.S.– Mexico border. They met their coyote, who took them by car into the mountains of northern Mexico. After spending the night in a makeshift campground, they started their hike into the United States.

The journey through mountains and forests was not for the ill bodied or weak minded. The hike involved high elevations and threats from animals and other travelers, all under the cover of darkness. There was little time for sleep, food, or water. Getting across the border was actually not that hard. It was not being caught by border patrol officers and returned back to Mexico that was more challenging. Topping it all off, Maria was getting sick. She was only fifteen and just not strong enough for the journey.

The first attempt to cross the border was unsuccessful. They were apprehended in a field, charged with illegally crossing the border, and driven back to Mexico. On day two, the same scene played out. After being caught twice by border agents, they considered giving up or at least trying again later. But this would mean staying in Tijuana until they could raise enough cash to hire the coyote again. Even though Maria was exhausted, they decided to make one more try, this time going a different way.

Although they did not consider themselves very religious, if there was ever a time to pray, it was now. All three were nearing their physical and mental limits. Trust in their God was almost all they could hold onto. In those moments when they had to be motionless to avoid detection by border police, Lucinda would grab Pedro’s hand and pray silently. It provided some peace before the next few steps ahead.

On the third attempt, Pedro and the coyote took turns carrying Maria on their backs. Their food and water rations were gone. It was just them, the brutal wilderness, and U.S. immigration officers. But before dawn, they managed to reach the parked van about two miles into the United States. Pedro got in, started the engine, and did not stop driving until he reached Lucinda’s uncle’s house in Los Angeles. After taking a few days to recover from the journey, they took a flight from Los Angeles to New Jersey to meet up with Lucinda’s brother and begin their new lives.

What Is the Religion of International Movers?

Pedro, Lucinda, and Maria’s journey is a true story of three people traveling the world’s largest immigration corridor. Twelve million people born in Mexico now live in the United States, many of them having made a similar journey.2 Add several million more migrants from other Central American countries who have moved to the United States, and the population of immigrants who have moved from countries south of the U.S. border numbers over twenty million people now living in the United States.

However, the migration of people across the southern U.S. border represents only about 10 percent of the world’s 215 million international migrants. Although movement north into the United States is high, moving across an international border is a rare event — only about 3 percent of the world’s population has done it. But if all the world’s migrants were to live in a single country, it would be the world’s fourth largest — smaller than Indonesia, but larger than Brazil.

Of these 215 million, about four in ten live in North America or Western Europe.3 The United States leads the world with more than 42 million immigrants, or about one in five of all the world’s migrants. Other top countries include Germany (10.8 million), Canada (7.2 million), France (6.7 million), the United Kingdom (6.5 million), and Spain (6.4 million). In these countries, immigrants constitute 10 percent or more of the total populations. Consequently, these countries in North America and Western Europe have been studied more than other immigrant destinations.

But where do these millions of migrants come from? Most migrants move from nearby countries where they can travel rather inexpensively across land or narrow sea borders. Not everyone crosses borders under darkness like Pedro and Lucinda, but many have. And illegal crossings aren’t commonplace only in deserts of the southwestern United States. They are also an issue for European beach communities in Italy and Spain as well as small villages in Bulgaria and Greece. The promise of a better life in the United States or Europe is too great for migrants not to try the terrorizing and potentially deadly journey.

Other migrants move in a more formalized manner, at least from the government’s perspective. For example, the United States annually accepts more than a million permanent residents.4 About a quarter-million immigrants enter Canada each year, often after working through a point-based immigration system where language, family connections, and skills determine acceptance into the country.5 Migrants come into Western Europe from other countries in the European Union like Poland and Romania. These migrants have the legal right to find jobs in other European countries, and many have found better jobs in the UK, Italy, or Spain. But a large number of Europe’s immigrants have also come from North Africa and Turkey. These immigrants join other family members already living in Europe. Additionally, countries in Europe and North America annually accept thousands of refugees from all around the world.

In sum, most migrants to the United States and Western Europe have moved from neighboring countries or regions of the world. For example, more than half, or nearly twenty-five million, of the immigrants living in the United States have moved from the Americas, most from Mexico and other countries in Central America and the Caribbean. Most of the nearly forty million migrants who have moved into Western Europe came either from other European countries in Central or Eastern Europe or from neighboring countries in North Africa (for example, Morocco and Algeria) or nearby Turkey. Canada is an exception to this general rule as most of its immigrants have not come from nearby countries, but from Europe and Asia.

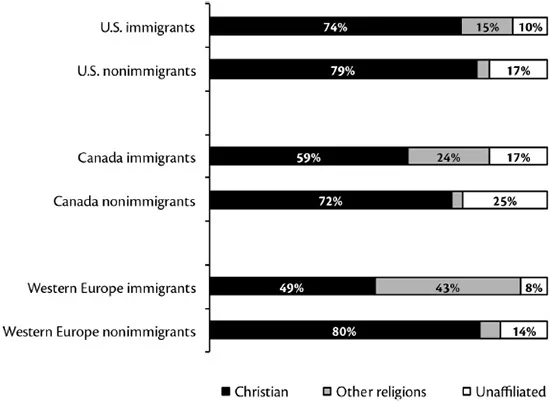

But migrants bring more than their nationality with them; they also bring their religion. Christianity comes to the United States with Latin American immigrants. Because of such high migration from south of the border, a majority of immigrants in the United States are Christian. In fact, about three in four U.S. immigrants have some Christian background, whether it is Catholic, Protestant, or some other Christian heritage. By contrast, the makeup of immigrants in Europe is not as Christian. Although immigrants from other European countries are mostly Christian, an almost equal number of non-Christian immigrants, mostly Muslim, also live in Europe. In fact, there are about as many Muslim immigrants in Western Europe as there are Christian immigrants. Canada is in the middle of this Christian/non-Christian balance of immigrants. Canada has a religiously mixed immigrant population, with a slight majority of immigrants in Canada having a Christian affiliation but sizeable shares also belonging to some other religion or claiming no religious affiliation.

Figure 1.1. Religious distribution of immigrants and nonimmigrants in 2010. (Pew Research Center’s Global Religion and Migration Database 2012; Pew Research Center’s Global Religious Landscape 2012)

Percentages don’t tell the whole story, however. On the world stage, the sheer volume of migration to the United States makes it the largest recipient of not only Christian but also Buddhist and religiously unaffiliated migrants. The United States likewise holds the second spot for the most Jewish immigrants (after Israel) and Hindu immigrants (after India). On the other side of the Atlantic, many European countries are also top destinations for the world’s Christian migrants. But unlike the United States, European countries like Germany and France are prominent destinations for the world’s Muslim migrants.

The United States, Western Europe, and Canada are all majority Christian environments or contexts, yet they have a sizeable number of people with no religious affiliation. But broad differences in the religious breakdown of migrants in these contexts provide for a different concept of immigrants in each place. In the United States, immigrants are probably described more by their national origins than by their religion. Since the great majority is Christian or claims no religion at all — two of the most common expressions of faith within the United States — the general religious breakdown of immigrants in the United States is not that different from the percentages in the country as a whole. Partly because there is not much religious difference, Americans tend to categorize immigrants by their racial or ethnic heritage. This is especially true given America’s experience with slavery and the civil rights movement — ethnic/racial distinctions have been historically more important in the United States.6

For example, when Pedro and Lucinda eventually made their home in New Jersey, they encountered many difficulties, but religion was not one of them. People in their small New Jersey town didn’t look down on them for being Catholic. The town already had two Catholic churches and they were well-respected institutions in the community. In fact, one of the local parishes had a weekly mass in Spanish and even had a Spanish-speaking priest from Colombia. When Pedro and Lucinda did feel unwelcome, it was because they were Mexican.

In Europe, however, the religious identity and breakdown of immigrants is far more consequential. Ask the several thousand Mohammeds or Fatimas living in Western Europe how they think they are viewed by the public, and they will most likely say they are understood first as Muslims before being recognized by their nationality or ethnic group.7 Most European countries were founded with religious differences in mind, often involving wars between Protestants and Catholics.8 Even though many people in Europe don’t attend church that much compared to those in the United States, some European countries have an official church — an entirely foreign idea to the United States, where church and state are legally separate. Add to this a Muslim immigrant population in Europe that is about equal in size to its Christian immigrant population, and immigrants become labeled more frequently by religious terms than in the United States. In fact, the most common image brought to mind when Europeans hear the word “immigrant” is a Muslim.9

Canada, however, with its greater assortment of immigrant religious groups and national origins of immigrants, fits somewhere between the American and European contexts.10 Relative to the United States and Europe, Canada’s share of immigrants belonging to religious minorities (non-Christian) is not as large as Europe’s but also not as small as the United States’. In this way, Canada’s immigrants may be viewed in more religiously and nationally diverse terms, easily adding to Canada’s image as a multicultural country.11

All in all, the majority of immigrants in the United States are Christian, whereas about equal shares of immigrants living in Western Europe belong to Christian and non-Christian (mainly Muslim) religious groups. This demographic contrast presents different images of immigrants in each context. Whereas religious differences in the United States do not seem to be that important in describing immigrant populations, religion is an important characteristic in describing immigrants in Europe, particularly in setting apart Muslim immigrants from other immigrants.

Which Religious Groups Are More Likely to Move and to Where?

Why is the U.S. immigrant population mostly Christian, Western Europe’s population split between Christian and Muslim immigrants, and Canada a bit of both? Are some religious groups more likely to move to certain places than to others? Or, are these statistics a byproduct of immigrants who would have moved anyway despite their religious background?

Many factors lead people to move across an international border. The migration decision is not a casual one but is filled with complex motives, situations, and conditions, in both the origin and the destination country. Some authors say migration involves a set of push and pull factors, often related to economic concerns.12 This economic model is a simple example of economics 101 — people living in poor economies with limited job opportunities are economically attracted to economies that are more developed and offer well-paying jobs. But immigrants consider many other factors, such as their family situation, likelihood of getting a job in the destination country, language concerns, and ability to manage once they arrive.

The total set of circumstances leading people to migrate is called “cumulative causation.”13 Although differences between national economies can lead people to move from poor to rich countries, there are many more reasons why individuals and groups move across international borders. These causes often add up to produce a migrant flow that is almost self-sustaining, lasting for several years or perhaps generations.

Economists tell us that potential migrants will include many factors on their “reasons to go” or “reasons to stay” lists. Some will include the chances of finding a job and differences in pay for the two countries, both in the short term and the long term. Others will include anticipated cultural, linguistic, and social challenges in adapting to a new place. Most potential migrants will estimate the cost of moving, including the safety risks and the up-front cash they may need to pay to enter the country. But of course, borders are not wide open. National governments may deny the entry of would-be migrants. Or unofficial means of crossing the border may be too dangerous. At the end of the day, if the would-be migrant’s list of pros is greater than the cons and there is a way to enter the country, migration theorists say the would-be migrant will make the move.

But migrants do not act in a vacuum. They also have to consider their families, both immediate and extended. People may move internationall...