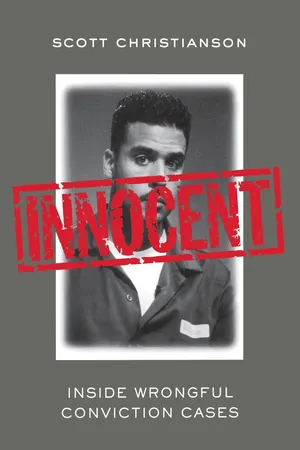

![]()

My guiding principle is this:

Guilt is never to be doubted.

—Franz Kafka, In the Penal Colony (1914)

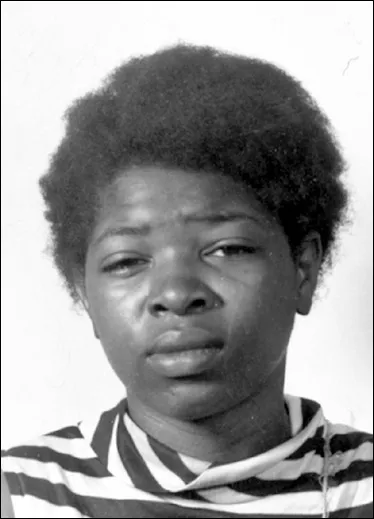

Betty Tyson mugshot. Courtesy of Rochester Democrat and Chronicle.

![]()

Introduction

Some hard-liners deny that anyone ever gets wrongly convicted. Those in prison, they say, must be guilty of something—otherwise they wouldn’t be imprisoned. As they see it, reversals, vacations, or dismissals don’t necessarily prove that the defendant was really innocent—just that he somehow “got off.” Only the guilty get legally executed; a prisoner freed from death row by DNA demonstrates that “the system works”; the fact that the defendant was erroneously convicted and imprisoned, maybe for years, before an appellate court addressed the problem to them simply represents an inconvenience. Indeed, as far as some naysayers are concerned, the only innocent ones are the unborn. And besides, some assert, the chimera of “innocents” can distract from the overriding problem of what to do about the guilty.

Most rational observers, however, probably recognize that, in addition to its other shortcomings, the criminal justice system produces an unknown number of erroneous determinations of innocence and guilt. Honest mistakes happen. So do dishonest ones. The rich enjoy every kind of protection, but some people are wrongly judged and punished. Usually the defendants adversely affected are poor persons of color. Many members of the public also realize that the criminal justice system tends to circle its wagons. Cops stick together, prosecutors mobilize to ward off any legal challenge, and judges tend to uphold the actions of other judges—tendencies that may make it all the more difficult for the wrongly convicted person to prove his or her innocence.

This book looks inside some actual, specific cases involving individuals who were convicted and imprisoned for crimes they didn’t commit—defendants who were innocent although proven guilty—and at the efforts to undo the convictions. A brief graphic rendition is offered for each case. The compilation isn’t exhaustive (it probably only scratches the surface), but it reflects a significant problem. Although all the wrongful convictions described herein happened in New York—a state that, in legal matters, is generally considered relatively advanced and sophisticated and often regarded as one of the best—maybe finding such a state of affairs in one of the better places will also raise serious questions about what goes on in the worst. Certainly such problems are not confined to Illinois and Texas—they exist in every state and each jurisdiction.

Most of the cases featured in the book involved a situation where a jury’s verdict was overturned and judicial proceedings resulted in what many reasonable observers may construe as an “exoneration,” meaning that the defendant was ultimately found blameless. In some of the cases, the State Court of Claims even awarded civil damages pursuant to the Wrongful Conviction and Imprisonment Act of 1984, leaving little doubt that mistakes had resulted in the wrongful imprisonment of an innocent person. In such cases, the defendant’s innocence literally had to be and was legally proven. This constitutes an extremely high standard—higher than any prosecutor ever has to meet.

The New York statute requires claimants to establish in pleadings that the conviction was reversed or vacated and that the accusatory instrument was dismissed; or, if a new trial was ordered, either that they were found not guilty or the accusatory instrument was dismissed without a trial. The statute also stipulates that the claimant must establish that the reversal or vacation of the conviction, as well as the dismissal of the accusatory instrument, was made on one or more specific grounds under the Criminal Procedure Law. The act doesn’t include all possible grounds consistent with innocence on which a case may be dismissed. It also contains the misleading phrase “in furtherance of justice,” which many observers might interpret as being consistent with a proven claim of innocence—yet a claimant whose indictment was dismissed for this reason will not be able to meet the conditions for bringing a claim under the Wrongful Conviction and Imprisonment Act, even if he or she was innocent. Finally, the statute asks claimants to establish in pleadings a substantial likelihood of prevailing at trial; for after a person’s conviction has been reversed and the accusatory instrument has been dismissed, the claimant must also prove his or her innocence to the Court of Claims judge by “clear and convincing evidence.”

Since the act took effect, fewer than twenty persons have received awards. This includes only a tiny fraction of all wrongful convictions. Unlike other jurisdictions, New York doesn’t set an upper limit on the amount it will pay. So far, the biggest individual award has been $1.9 million and the smallest have been $40,000. From January 1, 1985 to June 25, 2001, 165 claims were filed, 131 claims dismissed, 22 claims pending, and 12 awards made. New York is considered the most generous state in compensating wrongful convictions. In thirty-six other states, wrongfully convicted persons are legally barred from recovering damages in a court of law.

Besides including some recently settled matters that have passed muster with the Court of Claims, this book also recalls a few notable wrongful conviction cases from earlier eras as a reminder that the problem isn’t new and that a single case (such as Whitmore) can sometimes change a whole system.

When this project was started, I selected twelve convicted persons who were still in prison. Not all the convictions in the book were eventually undone, however. At this writing, six have had their convictions reversed and seven of the twelve defendants (Fernando Bermudez, Charles Hamilton, Patsy Kelly Jarrett, Emel McDowell, Rubin Ortega, Frank Sterling, and Martin Tankleff) are still in prison, fighting to be cleared, after serving long terms. Some of them seem almost to have been forgotten by the outside world. But they are excited by the prospect of suddenly winning in court, like others they’ve read about in the newspapers. Since this book was started, five of the featured subjects who were incarcerated (Lamont Branch, Anthony Faison, Ruben Montalvo, Jose Morales, and Kenneth Pavel) eventually won their freedom, and they were moved to the “exonerated” column. A sixth, Rubin Ortega, was awaiting action by the district attorney. Maybe more movement of this sort will continue to occur over time—but maybe it won’t. After all, it’s a lot easier to find someone guilty than it is later to prove him innocent; thus it’s likely that some of these convicted-but-not-exonerated persons will never be cleared, never be freed—despite all the evidence in their favor. At any rate, one shouldn’t conclude that “the system works.” If it did, there wouldn’t be any need for this book.

For several decades, a smattering of newspaper stories, books, television pieces, and Hollywood films have focused on the plight of wrongfully convicted persons. Such cries have helped a few prisoners win their freedom. These stories are the rare exception, however, not the rule. More often than not, media outlets represent the world in terms of black and white and good and evil, just as the adversarial system of criminal law clings to Manichaean notions of guilt or innocence, even though the real world is often gray, filled with contradictions, and plagued by doubts. In some instances, sensational, erroneous, or biased news coverage helped lead to the conviction in the first place.

Generally speaking, the news media provide precious little independent or enterprising coverage of criminal cases. If the media follow these cases at all, they tend to dutifully rely on information provided by the police and the courts. Court or legal reporting largely consists of selective trial coverage. Most journalists aren’t equipped or inclined to do the tremendous work required to cover a case properly or to scrutinize a criminal conviction, much less to wage the kind of campaign it takes to undo an unjust result. Only a tiny handful of major city newspapers are capable of performing such a role. Even if they inclined to try, alternative newspapers and magazines generally lack the necessary credibility and stature to be effective. Local and even national television news operations rarely initiate such reports. As a result, most areas of the state are left without any likely advocate able to take a second look at a conviction. Yet without investigative reporting by a well-respected news organization, many cases of injustice probably would never result in an amendment—there never would be a reversed conviction or a decision to drop the charges or a finding of liability.

The book’s emphasis on journalistic as well as legal aspects reflects the role that publicity plays in the making of a successful wrongful conviction claim, because, quite simply, without strong media support along with their legal assistance, some defendants never would stand a chance. Fortunately for a few convicted persons, there have been exceptions to the rule—investigative reporters or columnists who pursued the truth and helped correct an injustice. Based on my own first-hand experience as a reporter, I know how difficult it is to prove someone’s innocence—even by journalistic standards.

Unfortunately, not much is known about the current nature and extent of wrongful conviction. The state does not maintain a master list of its mistakes. Since Edwin M. Borchard’s pathbreaking book Convicting the Innocent: Sixty-five Actual Errors of Criminal Justice (1932), a few scholars and writers have sought to document wrongful conviction cases in the United States. Following up on an earlier article published in the Stanford Law Review (1987), Radelet and Bedau, writing with Putnam (1996) documented four hundred cases of wrongful conviction, including twenty-three wrongful executions in New York. A study by Huff, Rattner, and Sagarin (1996)—largely based on a survey of criminal justice officials—extrapolated that ten thousand persons per year are wrongfully convicted of serious crimes in the United States. Estimates have ranged as high as 3 to 10 percent of all felony convictions—a staggering number. Yet there is no official database. For a time it seemed that every daily newspaper brought with it mention of another case. But since September 11, 2001, the frequency has drastically decreased. Other problems now seem paramount in the public mind, and “innocence” to some officials has become archaic and quaint—a luxury we can no longer afford.

During the last decade or so, however, the new marvel of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) tests positively established, with a high level of scientific certainty, that some convicted persons didn’t commit the crime in question. In 1996 the National Institute of Justice of the U.S. Department of Justice issued a report documenting twenty-eight wrongful convictions for murder or sexual assault in fourteen state courts and the District of Columbia wherein postconviction DNA comparison had proven to a scientific certainty that the convicted persons were not guilty.

This powerful scientific tool has suddenly stripped away the armor of infallibility from capital punishment adjudication. As one hundred condemned persons have been freed from death row based on DNA tests and other determinations of wrongful conviction, public support for the death penalty has eroded and prompted at least two governors to establish a moratorium on executions. Yet DNA testing hasn’t killed capital punishment, and the parade of errors exposed by DNA hasn’t even produced major criminal justice reforms. It may even provide a false sense of security.

This book includes only a few recent episodes where DNA was used or is being sought to help prove a wrongful conviction in New York. As with the vast majority of criminal cases everywhere, DNA seldom enters the picture—whether to convict someone, to rule out a potential suspect, or to free the wrongfully convicted. Unfortunately, DNA can’t be counted on to solve most crimes or to overturn the vast majority of wrongful convictions. It isn’t a magic bullet or a panacea. And even DNA testing is subject to human error. But it can help to rule out some innocents.

Earlier scholarly studies (by Borchard, Bedau and Radelet, and others) prominently cited several New York death penalty cases among their lists of persons wrongfully executed or almost executed. Rosenbaum (1990–91) cataloged fifty-nine wrongful homicide convictions in New York State from 1965 to 1988. Most of the cases presented in this book were not capital affairs, though a number were murder cases that could have been prosecuted under the state’s later death penalty statute or the federal death penalty provisions, both of which were enacted in the 1990s.

It is important to recognize that death penalty cases are not the only instances in which miscarriages of justice have occurred. Several other cases described here involved crimes less serious than murder, and a few convictions came about as a result of a guilty plea rather than a trial verdict.

In fact, wrongful convictions carry serious consequences wherever the deprivation of liberty is at stake. The problem often gets addressed only where very long sentences are involved, because it usually takes several years to gain a reversal, and by then, most criminals are already released. Few legal players pause to consider whether the vast bulk of offenders, who serve two years or so in prison, may include their share of wrongful convictions—even if some of them pleaded guilty. But that is very likely the case.

Under New York’s Criminal Procedure Law, a convicted defendant in a noncapital case may challenge his conviction by raising matters outside the trial record, such as newly discovered evidence or ineffective assistance of counsel. This requires the defendant to go back before the same court where the conviction occurred. Judges do not relish such an event. To appeal the judgment in state court, the defendant must take the matter before the Appellate Division (the intermediate state court of appeal). Only after presenting the claims in state court can the defendant then file a habeas corpus challenge in U.S. District Court. But habeas corpus offers slim hope. And clemency offers virtually no hope at all—governors and presidents do not pardon prisoners based on innocence.

Rather than talk about wrongful conviction in global terms, the book tries briefly to examine a number of specific cases in capsule form—a difficult task given the complexities of the events and issues involved. Concise accounts can never do justice to the sufferings endured by so many or convey the hard work put in by all the good police, prosecutors, defense lawyers, investigators, advocates, and judges who struggled to right such wrongs. But they can reveal some common patterns and general characteristics. Collectively, they may provide insight into some of the causes and consequences of wrongful conviction. It is hoped that some of the humanity of those involved will come through.

Most of the material in the book was gleaned from legal case files—briefs, smoking-gun memoranda, investigative reports, police videotapes, judicial opinions, and the like—that were shared by defense attorneys, defendants, and court officials. The New York Police Department was unwilling to provide arrest mug shot photographs, so other images had to be compiled. Data were also obtained from interviews conducted in 2001 and early 2002 with more than two hundred persons. Additional information was gathered from books and articles that appeared in newspapers, magazines, and journals. All this has been filtered through my own professional experience in the criminal justice system, which goes back more than thirty years. I am not a lawyer, but my Ph.D. in criminal justice and work in the trenches has entailed gaining familiarity with the criminal justice process.

The stories are grouped according to the some of the variables that are generally recognized as major contributing factors to wrongful convictions—factors such as presumed guilt, mistaken identification, ineffective counsel, eyewitness perjury, false confessions, police misconduct, prosecutorial misconduct, fabrication of evidence, and forensics. However, these categories are both artificial and neither all-inclusive nor exclusive. Other reasons contribute to miscarriages of justice. By all accounts, most wrongful convictions involve more than one underlying cause, and some invol...