![]()

1

These Kids Today

Hold on to your underwear for this one.

—Michelle Burford on Oprah, 2003

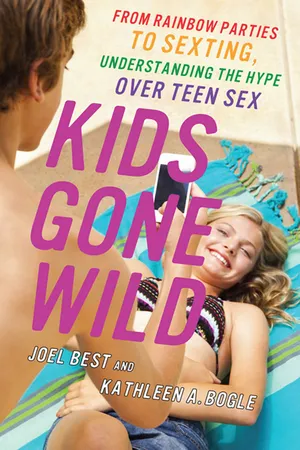

Most of us—parents in particular—try to protect children from sexual dangers. The last two decades of the twentieth century featured intense, heavily publicized campaigns against pedophiles, child pornographers, and other bad guys who sexually menaced innocent, vulnerable young people.1 But as the new millennium began, the focus seemed to shift. People talked less about stranger danger and more about the sexual threats young people posed to themselves. From rainbow parties to sex bracelets to sexting, kids seemed to be going wild. What, the media repeatedly asked, were average parents supposed to do to keep their children safe from licentious debauchery? Of course, this was hardly a new theme; late twentieth-century commentators worried about reducing teen pregnancy and encouraging safe sex, just as previous generations had tried to supervise courtship and going steady. But there was a new fascination with the dangers posed by ever younger people—even elementary school students—engaging in apparently new, often so shocking that they could not be named, sexual practices.

These concerns focused on threats to children’s innocence. Each focused on a different age group, from children in elementary school to teens in high school.

Sex Bracelets

Children in primary school were reported to be wearing sex bracelets. Also known as shag bands,2 gel bracelets, and jelly bracelets,3 these were a child’s fashion accessory. They were inexpensive, thin, o-ring bracelets, made from a supple plastic gel, sold in a variety of colors, and most often worn by grade school and junior high school children, usually girls. The bracelets first became popular in the 1980s, when they were featured in Madonna and Cindi Lauper videos. Then, beginning in 2003, they gained new notoriety with warnings linking them to sexual behavior, with different colored bands said to represent different sexual acts, ranging from the relatively innocent (hugging, kissing) to some that seemed shocking (fisting, analingus). There were three major stories about the bracelets’ meanings: (1) bracelets’ colors signified which sexual acts the wearer had already performed; (2) bracelets’ colors signified which sexual acts the wearer was willing to perform; or, most commonly, (3) if someone snapped a bracelet and managed to break it, the wearer had to perform the sexual act associated with that bracelet’s color.4

Some commentators insisted that shag bands encouraged sexual misbehavior among the young; one referred to the sex-bracelet story as “one of the most dramatic media narratives about teen sex in recent years.”5 However, news coverage usually associated sex bracelets with younger preteens: in 2004, a Queens, New York, fifth grader attracted national attention when it was revealed she was buying bracelets for $1 and selling them to classmates for $1.25; five years later, Britain’s Sun accompanied its story headlined “Bracelet Which Means Your Child Is Having SEX” with a picture of a mother and her eight-year-old daughter. Still, even the most fevered imaginations were likely to doubt that fisting had become a widespread practice on school playgrounds, and some commentators argued that shag bands were best understood as a contemporary legend, one of those supposedly true tales that spreads through the population.

However exaggerated, even ridiculous, the claims about sex bracelets might seem, the tale’s spread was impressively wide. The story first gained wide currency in the United States in 2003, but by 2010, it could be found throughout the world—in England, Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany, and elsewhere in Europe and also in Brazil, Australia, South Korea, and other countries. Many people who heard and repeated the sex-bracelet story took it quite seriously and insisted that shag bands were a real, deeply troubling social problem.

Rainbow Parties

A similar concern, most often associated with junior high school students, involved rainbow parties. At these gatherings, each girl supposedly wore a different color of lipstick and then performed oral sex on each of the boys in succession, leaving rainbows of multicolored lipstick traces. The story was mentioned in a 2002 book, Epidemic: How Teen Sex Is Killing Our Kids, but did not come to widespread attention until an episode of The Oprah Winfrey Show, first broadcast in October 2003. Oprah asked her guest, journalist Michelle Burford, “Are rainbow parties pretty common?” and was told, “Among the 50 girls I talked to … this was pervasive.”6 In 2005, Rainbow Party, a novel aimed at young adults, inspired a good deal of critical commentary about the appropriateness of oral sex as a theme for adolescent fiction and about whether libraries should carry the book.7

The tale was linked to broader warnings about epidemic oral sex among teens that spread in the aftermath of the Monica Lewinsky scandal. Tom Wolfe, for instance, claimed in 2000 that junior high schools had a “new discipline problem”: “Thirteen- and fourteen-year-old girls were getting down on their knees and fellating boys in corridors and stairwells during the two-minute break between classes.”8 Worries about train parties—“boys lined up on one side of the room, girls working their way down the row”—preceded the rainbow-party story, and commentators marveled that oral sex, once “considered to be an act even more intimate than that of intercourse,” was now “largely seen as a safer, easier, less messy, and more impersonal precursor to or substitute for vaginal intercourse.”9

In many ways, concerns about rainbow parties paralleled those about sex bracelets. In both cases, children or early adolescents were depicted as having more sexual knowledge than their counterparts in earlier generations had. Both sets of claims warned that young people’s—and, in particular, girls’—sexual behaviors were governed by new customs (an obligation to engage in sexual acts when a bracelet was broken or to perform oral sex on all the boys at a rainbow party) that seemed to divorce sex from love and to foster promiscuity. Both concerns spread widely, even across international boundaries. And both led to debates, with skeptics dismissing the stories as false, highly unlikely, or at least exaggerated, as being merely contemporary legends.

Sexting

As the century’s first decade wound to a close, there were news reports that high school students were sexting (using their cell phones to exchange sexual text messages and images). By June 2008, the Associated Press picked up the story with the headline “Teens Are Sending Nude Photos via Cell Phone.”10 In the digital age, what might be intended as a private communication (a partially nude self-portrait sent by a teen to her boyfriend) could become publicly available. In contrast to the sex-bracelet and rainbow-party stories, there was plenty of evidence that sexting really occurred. And sexting attracted extensive media attention, with reports from all across the country of teens (and even preteens) who had been caught sending sexual messages and the trouble they faced as a result. Parents were forced to respond, school administrators had to draft new policies, and law enforcement officials and legislators found themselves struggling with thorny questions: Was sexting a crime? Were these images child pornography? Did these adolescents need to be registered as sex offenders?

Although no one considered claims about sexting to be untrue, there were varied reactions to the story as it unfolded. Many people considered sexting to be very troubling behavior, another sign of kids going wild, and called for something to be done to stop teens from doing it, while others thought the matter was being blown out of proportion and found the proposals to curtail it excessive. Although there was debate over what to do about sexting, most agreed that it was a problem that needed attention. And it was not only adults in the U.S. who were worried about sexting; the issue made headlines in many other English-speaking countries as well.

While worries that children and youths were in danger from sexually exploitative adults had not vanished, the focus for public concern seemed to have shifted to worries that young people, especially girls, were sexually out of control. Even college-age young adults were not immune from scrutiny. There were warnings that hooking up was rampant on campus, posing threats of date rape, STDs, and other moral hazards. Although sex bracelets, rainbow parties, and sexting were not the only kids’ activities that concerned adults, these issues received extraordinary attention in the media, even in legislative chambers, and they also became the subject of everyday conversations among ordinary people. There were debates: some people dismissed sex bracelets and rainbow parties as little more than rumors, figments of overactive adult imaginations, just as others argued that critics had exaggerated the dangers of sexting; but there were those who insisted that the threats were all too real and who called for action. This book explores how people handled claims that children and adolescents were engaged in troubling new sexual practices. While we will occasionally refer to hooking up and other issues, our focus will be on the three high-visibility concerns about younger kids: sex bracelets, rainbow parties, and sexting.

Concerns in Context

Concerns about sex bracelets, rainbow parties, and sexting followed a familiar pattern. In each case, claims that these were new forms of sexual behavior inspired a wave of commentary: journalists, cable-TV pundits, bloggers, and ordinary citizens repeated the claims (“Do you realize what kids today are doing?”) and debated their significance (with responses ranging from “That’s ridiculous!” to “Aw, we used to do the same thing when I was young” to “No! This is a disturbing new trend”). The way in which people reacted to these stories was likely influenced by a whole host of things: their own childhood experiences, their political leanings, and their exposure to related stories about kids and sex, just to name a few. In other words, concerns do not emerge in a vacuum. By understanding the cultural context in which these stories materialized, we can better explain the positions people took in response.

Concern over Sexual Play

Sexual play has historically been a subject of concern; after all, it is a common, although far from universal, activity during childhood and adolescence. It can be structured, as in the kissing games cataloged by folklorists. Thus, one 1959 analysis noted that preadolescents played “chasing kiss games,” often on the playground: “In ‘Freeze Tag’ … you are permitted to kiss, and to chase, but only according to the rules.” At junior high school gatherings, groups played “mixing kiss games” (e.g., “Post Office” or “Spin the Bottle”), in which “pairing occurs in the games but is characteristically of a momentary sort.”11 Older adolescents played “couple kiss games” that offer occasions for kissing (e.g., “Perdiddle” allowed a male who spotted a car with a missing headlight to kiss his date). Particularly at younger ages, kissing games seem to be largely about pursuit and poise, about exploring the boundaries of gender and daring to engage in a bit of intimacy.

One way to think about sex bracelets is in relation to the tradition of chasing kiss games: break the appropriate bracelet, and the wearer is obliged to hug or kiss. Claims that boys who break sex bracelets will be rewarded with sexual favors also resemble earlier, parallel tales about various sorts of “sex coupons” (e.g., intact labels peeled from beverage bottles, pull tabs from cans, etc.) that could be redeemed for sexual intimacy.12 Similarly, stories about train parties and rainbow parties may seem less far-fetched because they suggest an escalation from earlier generations’ parties featuring mixing kiss games. And this escalation to wilder sexual behavior fits into what many Americans seem to believe about how today’s kids—especially girls—behave.

Of course, many adolescents engage in less structured sexual play—usually in couples, usually not including coitus—described in vague terms that shift over time. During the late nineteenth century, couples engaged in spooning or canoodling.13 In the 1920s, the terms petting, necking, and parking (the term originally referred to couples stopping on the dance floor—parking—to kiss) became popular.14 Making out seems to have emerged in the 1950s, hooking up even later.15

It is not as though there is anything new in worrying about youthful sexuality, although the concerns of earlier generations can seem quaint and amusing. For instance, during the 1920s, critics warned about petting parties. A front-page New York Times story (“Mothers Complain That Modern Girls ‘Vamp’ Their Sons at Petting Parties”) quoted Janet Richards (a frequent commentator on social issues):

The boys have gone to their mothers, said Miss Richards, and said: “Mother, it is so hard for me to be decent and live up to the standards you have set me, and to always keep in mind the loveliness and purity of girls. How can I do it with this cheek dancing, and if I pull away they call me a prude. And when I take a girl home in the way that you have told me is the proper fashion she is not satisfied and thinks I am slow.”16

Similarly, the 1950s witnessed warnings about the new practice of going steady: “A popular advice book for teenage girls argued that going steady inevitably led to heavy necking and thus to guilt for the rest of their lives. Better to date lots of strangers, the author insisted, than end up necking with a steady boyfriend.”17

Concerns about petting or going steady reflected worries about how social changes were affecting young people. As young people’s access to first automobiles and then disposable income spread during the first six decades of the twentieth century, flirtation and courtship were less likely to occur under the supervision of adults. New forms of popular culture seemed to promote sexual awakening: movies allowed audiences to envision how romances might be carried out; new clothing styles—particularly the flappers’ short skirts—revealed more flesh; and new music and dance styles seemed to promote sexuality. The troubled reactions to first jazz and then rock emphasized the primitive, sensual, uninhibited qualities of the new music.18 In part, these reactions reflected concerns about racial contamination, worries that white youths might be corrupted by black music. But this new music also seemed sexy; commentators seemed fixated on its intense rhythms and moaning sounds.

Throughout the twentieth century, there was a growing sense that young people were living in a new world that operated according to new rules, that sexual play was more open, more common, and more extreme than in their parents’ generations. Many people believed this was a slippery slope: movies put ideas into the heads of the young; fast music encouraged abandoning restraints; and, however innocent or playful petting might seem, it surely could lead to the loss of virginity, illegitimacy, and disgrace.

There is, then, a long line of commentators worrying about the sexual play of the young. Of course, what is considered shocking escalates with each generation: worries about close dancing become concerns about grinding, and anxieties about petting parties turn into stories about rainbow parties. Each generation’s critics have managed to warn about a revolution in sexual manners, even as they often failed to acknowledge the longer history of concern about youthful sexual play. The point is that concerns about sex bracelets, rainbow parties, and sexting tap into longstanding worries about the extent and nature of young people’s sexual activities today: believing that teen sex has become increasingly commonplace makes claims about organized oral-sex parties seem plausible.

Worrying about Kids

All three topics involved young people and sex, and the ways people responded to sex bracelets, rainbow parties, and sexting reflect a broader cultural context. Attitudes toward childhood and adolescent sexuality and sexual behavior fall into two broad camps. On the one hand, there are those who adopt what we might call a pragmatic stance. They argue that sexual curiosity and sexual expression are a f...