![]()

1

Enforcing Romantic Love through Immigration Law

After September 11th, the existential question of “Why do they [foreigners] hate us?” was hotly debated in the American media without any real conclusion ever being reached. This [article] seeks to answer the opposite question: “Why do they love us?”

—David Seminara, former consular officer

Huddled together at a party that gathered a growing community of Colombian women married to U.S. men, various women admitted to each other in Spanish that they did not love their U.S. husbands when they decided to marry and migrate to the United States.1 I discovered during my interviews with some of these women two years later that three of the women ended up falling in love with their husbands over time. One woman fell in love even after agreeing to pay a man $6,000 to marry her until she received her permanent residency. A couple of the other women’s relationships ended in divorce just a few years later (after they were granted permanent residency). One returned home soon after arriving because her husband realized he was not ready to share his life with someone. And another continues to be married despite not being in love. Women must guard their hushed exchanges about love (and its absence) closely, lest they be perceived as calculating and manipulative, prostitutes, lesbians, or even criminals of the state, if it were discovered that they took a chance on marriage, hoping that love or at least a mutually satisfying relationship would develop.

Even though transborder relationships and marriages might better resemble the kind of love that evolves from building trust and intimacy over time, spouses are required to profess romantic love in route, as they pass through the scrutinizing gaze of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Disclosing their lack of love is dangerous. Women could face steep fines (up to $250,000) and jail for five years, or ICE may choose to deport them if it found out they used marriage to gain state benefits. According to self-help books, love continues to be “at large” in a U.S. culture characterized by heightened modernity and alienation,2 a sentiment that in part shapes U.S. men’s expectations for heightened love, care, and sexual passion in Latin American women.3 At the same time, a white woman who attended the same party described this group of Colombian women as incapable of love because their harsh lives demand economic savvy, as opposed to the luxury of choice that being in love assumes.4

Part of the challenge of interviewing women about their private lives and desires at the tours and after migrating to the United States undoubtedly reflects their surveillance by family codes of respectability, but it also reveals their close monitoring by ICE when crossing the border. It is riskier for women to speak out than for men, complicating the ethnographic and feminist project of “giving voice” to Latin American women seeking a foreign marriage partner.5 For this reason, I tell this piece of the story through and beyond the accounts shared with me by women who migrate with their husbands to the United States. In Patricia Zavella’s articles on the construction of Chicana/Latina sexuality, she analyzes women’s cultural poetics, the ways women discuss their sexuality through discourses of juego y fuego (play and fire), to link local speech patterns with broader forms of gendered power relations as well as women’s resistance to control through sexual comportment.6 Even when it appears as though some Latinas may not directly contest power, it is through the poetics of silence that anthropologists bridge what is said with what cannot be expressed. Zavella argues, “Women’s cultural poetics, the social meaning of sexuality, entails struggling with the contradictions of repressive discourses and social practices that are often violent toward women and their desires.”7 In a similar vein, women’s silence—or even their attesting to being in love with their husbands—alerts us to the forms of surveillance and repression by immigration laws that determine eligibility for and the right to citizenship. By invoking “poetics,” I hope to shift the weight of women’s speech from willing deception and to crack open the possibility of other meanings to permeate. In addition, women’s reticence during interviews to voicing alternative understandings of marriage point to the cultural and social norms in both the United States and Latin America that yoke marriage and sexuality to love and reproduction, in opposition to the consumption of love in the marketplace. The irony of solidifying this moral separation by social dictates is that in popular culture, Western-style “romantic love” defies this separation between intimacy and marketplace exchange, as romance is fully intertwined with leisure and consumption.8 Yet here, even the bureaucratic functioning of the state is invested in the poetics of nation-building founded on the patriotic bonds of love.

The separation of innocent migrant marriages based on love versus fraudulent couplings entered into for self-gain took on an especially high tenor post-9/11, as immigration debates swerved back to the question stated earlier—not simply “Why do immigrants hate (attack) us?” but “Why do they love (marry) us?” The space between hate and love collapses through fears that terrorists and other unwanted migrants drag as newlyweds to enter the country. Other figures have similarly raised ire in the public when “imposters” attempt to take over an institution that is distinctly, or should I say exceptionally, American. While today these figures are gays, migrants, smugglers, and terrorists, historically the profile has changed depending on what body politic threatened to take hostage of love-based marriages and normative kin relations within the nation. In particular, some immigration advocates interpret the sharp rise in visa petitions for a foreign spouse as a potential national security threat and lobby for more rigorous investigation of these marriages. For example, David Seminara, a former consular officer, draws from ICE statistics to lobby for more stringent scrutiny of the alarming number of cases of immigrant marriage fraud. His article, written for the Center for Immigration Studies,9 equates an increase in foreign marriage with higher rates of fraud:

More than 25 percent of all green cards issued in 2007 were to the spouses of American citizens. In 2006 and 2007 there were nearly twice as many green cards issued to the spouses of American citizens than were issued for all employment-based immigration categories combined. The number of foreign nationals obtaining green cards based on marriage to an American has more than doubled since 1985, and has quintupled since 1970.10

Rather than scrutinize migrants for “fraudulent” love, I argue that there is a more complex story to understanding why marriages have quickly surpassed the numbers of employment visas, why love must accompany these marriages, and why foreign marriages have, since the 1980s, raised fears of fraud and the need for more stringent immigration surveillance. Immigration policies, since the inception of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) in 1891, have screened migrants as excludable based on an array of threats to the normative white family. And since the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act (amended in 1965), family reunification served as the route to legal migration.11 With the decline in alternative channels for “legal” migration, marriage becomes a desirable avenue for migrants who seek legitimate entry into the United States, the right to labor, mobility, and for some, the possibility of eventual legalization.

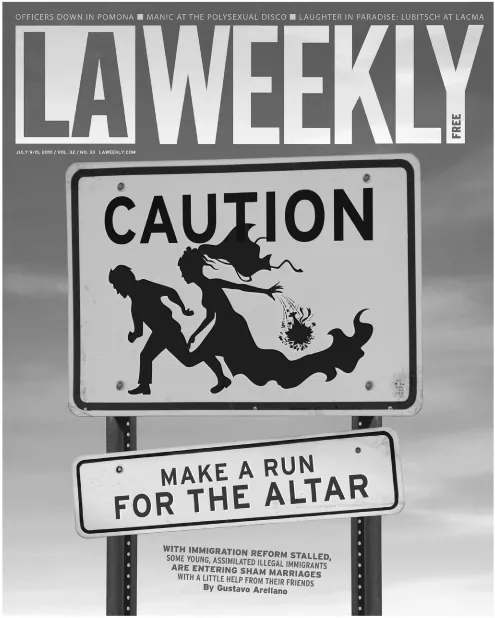

Fig. 1.1. L.A. Weekly, cover page, “Make a Run for the Altar” (July 8, 2010).

A recent article in the L.A. Weekly called “Make a Run for the Altar” describes how some citizen Latinas/os living in the United States exercise their right to marry an undocumented migrant to protest the lack of other options for legalization for migrants who live and work in the United States. Figure 1.1 plays off of signs posted close to border-crossing areas in San Diego that caution drivers to watch out for people running across the highway. Here one is to be on the lookout for migrants involved in sham marriages who are running not across the border but to the altar to gain citizenship. In response to public fears that mass numbers of migrants are infiltrating the border through “sham marriages,” Gustavo Arrellano’s article debunks the criminality of migrant marriages through uncovering the deep political sentiments and affinities between Latino/a citizens and those without documents that motivate some to take great risks in marrying an undocumented friend or fellow Latino/a migrant.12 The article finds that the penalties for marriage fraud do not stop some who see marriage as their only route to remain in the United States legally.13

Raging debates over what constitutes an “authentic” foreign marriage are curious given a lengthy 2010 study by the Pew Research Center that reports the finding that one in four Americans say marriage is obsolete.14 As traditional marriages continue to decline from the 1980s until today as the structure for intimacy, raising children, and family formation, the ideology of heterosexual marriage has surged rather than waned in political and immigration debates in the United States. Some questions that emerge from this contradiction between practices of intimacy and the intent of the law are: What norms are embedded within immigration policies that have, since the inception of the INS in 1891, focused on reproduction and the family? How do these historical debates inform why foreign cybermarriages, and foreign women’s migration from developing to first-world nations more broadly, are so closely monitored and debated? What foundational fears and beliefs do foreign marriage migrants threaten?

My desire to contest official depictions of foreign marriages as a potential threat by generating countervoices of Latin American women who are “truly in love” would only reproduce neoliberal state policies. Consular and ICE inspections of “authentic” foreign marriage justifies the state’s authority and power to ramp up border scrutiny in the name of protecting the rights and citizenship of the exceptional few. Instead, in this chapter, I argue that the U.S. state plays a critical role—via immigration law, politics, and procedures—in shaping how foreign marriage migrants express intimacy and move across borders as potential citizens rather than second-class subjects. I am not interested in proving whether love is true or not in these arrangements. Instead, I contend that romantic love is a compulsory sentiment for migrants to prove their potential for modern citizenship. Women’s practices of citizenship and self-making as subjects in love, and thus as innocent and pliable, are far from natural but instead are necessary to projecting their sexual labor as moral and their bodies as productive rather than a risk to the nation. Immigration policies perpetuate deeply engrained values of neoliberalism through laws that scrutinize “risky” foreign marriage migrants or those thought to fraudulently enter marriage for the economic perks.

In the chapter, then, I begin with an analysis of immigration and naturalization laws that have historically protected rights and citizenship obligations through marriage. This history is crucial to understanding how the scrutiny of foreign marriages, and the cybermarriage industry in particular, emerges in immigration debates beginning during the turn of the twentieth century and continuing into the 1980s and into the present. The 1980s signify a key moment for interrogating the tense ties between political debates on protecting family values and the rise of a backlash against those who threaten the nation via fraudulent marriages. Scholars have made important contributions in examining the role of the law in policing “foreign” bodies that are deemed (sexually) excessive and thus a threat to the normative state—such as in the case of lesbians, gays, polygamists, sex workers, and terrorists who attempt to migrate across borders.15 There has been little discussion, however, about the way women’s seemingly normative migration through marriage poses a similar perceived threat to the nation and thus is subject to constant scrutiny and surveillance.16

ICE’s use of love as a barometer for determining migrant citizenship sets up a strict binary between intimacy, agency, and democracy, on the one hand, and relationships based on trade, exploitation, and anachronistic governance, on the other. Marriages agreed on outside the love bond smack of a forced contract that shadows the dark past of slavery thought to threaten the boundaries of the nation. Thus, by interrogating the foundational values of love and intimacy through the law’s scrutinizing gaze, the supposed naturalness of heterosexual love and marriage comes into question. Instead, these sentiments prove foundational to national ideologies, shaping the state’s odd role as an arbiter of love arrangements and rights.

The Making of (Sexual) Subjects via Immigration Laws

Marriage as a political institution has long defined women’s rights and obligations, especially since the nineteenth century, when, as argued by Linda Kerber, marriage law relied on a system of coverture that “transferred a woman’s civic identity to her husband at marriage, giving him the use and direction of her property throughout the marriage.”17 Marriage was an institution that entrenched gender roles into law, delineating rights and obligations, with the husband serving as the economic provider and family head, communicating his wife’s voting, jury, and contractual rights to the state.18 Coverture, a French term defining the system in which women’s rights were covered by their husbands, originated from a longer legacy of coverture defining unequal relations between parents and children as well as masters and slaves.19 The exchange of citizenship rights and obligations within marriage is often obscured, especially today through the ideology of equality embedded in romantic love. As we will see later in the chapter, changes to immigration policies after a 1985 Senate debate on fraudulent marriage resurrected a temporary system of coverture, as migrant women were forced to rely on their U.S. spouses for financial and legal support the first two years or so until their husbands petitioned for their permanent residency.

Furthermore, as argued by Peggy Pascoe, because marriage stretches seamlessly from romance to respectability to responsibility, it has extraordinary power to naturalize some social relationships and to stigmatize others as unnatural.20 The power of marriage to stigmatize, but also to distribute rights, has ignited some gay and lesbian activists to demand the right to marriage. Yet while some activists argue for inclusion based on mutual love and highlight the unequal distribution of political perks, rights, and benefits conferred through marriage, foreign marriage migrants must prove the marriage is based on love solely rather than economic benefits.21

The preoccupation with marriage in immigration law from the 1980s to the present builds on previous exclusion acts in which the state’s concern with national inclusion/exclusion and citizenship rights reproduced racialized norms concerning marriage and sexuality. More contemporary laws base exclusion on the potential for a migrant’s threat to national security. This is especially the case as media accounts have associated women’s migration and mobility with unruly and hypersexualized behavior.22 Immigration laws have long excluded women whose sexuality (determined through one’s race and class) outside marriage was associated with immorality, prostitution, or criminal deviance. As Eithne Luibhéid argues, family preference in U.S. immigration law has historically served a host of purposes including to maintain the heterosexual family unit and to construct women as dependent wives following pioneering migrant husbands; to protect whiteness; to prevent intermixing; to exclude women, especially prostitutes, who violated or threatened to dismantle the family structure; to bar married women whose childbearing was feared to result in the birth of “too many” poor children; and to generate explicit racial, ethnic, and class exclusions that helped to consolidate the “immigrant family” as necessarily ...