![]()

1

The Class Character of Boys Don’t Cry

What might be the value of reading Boys Don’t Cry (1999) as a social class narrative? More precisely, how might we interpret the film as a story of transgender becoming and punishment in a representational field whose class idioms are conspicuously coherent? I pose this question to explore popular discourses of transgender experience, the meanings of class belonging and difference in the commercial media, and the mediations of transgender embodiment and working-class life. The pattern I want to illustrate, which turns up again and again at the nexus of queerness and class, is the displacement of the trauma of one category onto the trauma of the other. In popular culture and its reception, queer and class suffering is an easy switch.

Such themes are amplified in Boys Don’t Cry by the film’s roots in the social reality of Brandon Teena’s life in the months before his death, naturalizing or at least stabilizing the film’s account of cultural locale and persona.1 Here, though, I want to emphasize the “based on” rather than the true story, to signify the continuities between text and life from which Boys Don’t Cry emerges as probably the best-known version of Brandon Teena’s death.

Brandon Teena—the person—has been described and redescribed by various interlocutors as alternately a young transman, a genetic girl, a tomboy, a teenage woman, a butch lesbian who passed as male in the absence of an affirming lesbian community, and as a universal subject who courageously sought to become his “true self.” These are not just variations, however, but claims, and each carries different political weight. For me, Brandon was a young, female-bodied person who identified and passed as a man, and whose physical style and attraction to heterosexual girls and women were expressions and confirmations of his gender identity.2 Whether and how Brandon might have further materialized his masculinity through hormone treatments or surgery had he the resources—and had he lived—is not clear.

In familiar parlance, Brandon was transgendered, though to my knowledge that is not a term he used to describe himself. In threatening contexts, for example in the sheriff’s recordings of investigative interviews following his rape,3 Brandon described himself in more clinical terms as having a “sexual identity crisis.” It is uncertain, however, exactly what that meant to him or whether he might have used other phrases on other occasions.

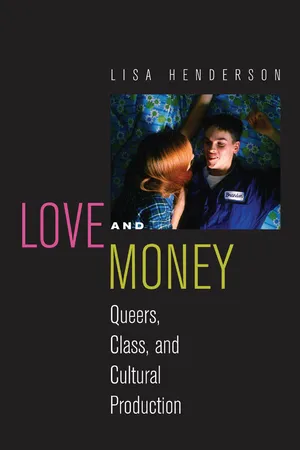

Lana and Brandon at pool table (still), The Brandon Teena Story © 1998 Bless Bless Productions.

In Boys Don’t Cry, the terms of Brandon’s gender identification are mixed. Brandon regards himself as a boy, though sometimes even his self-descriptions shift for strategic reasons. Others see him as a boy, too—until they stop doing so, at which point he is at the mercy of their chaotic and hostile attributions. He finally becomes a transitional body made violently accountable to gender binarism, permitting no alternative embodiment or subjectivity, demanding instead that both one’s body and claims about one’s self conform to (born) male masculinity or (born) female femininity and to heterosexuality as their normative counterpart. Brandon as a character is not quite exposed and killed for being a dyke (though he is sometimes identified as one), but as a freak, a gender liar whose nerve in reporting his rape provokes the homicidal rage and fear of his attackers, men whose masculine excess and precarious homosocial bond Brandon had earlier sought to be included in.

Boys Don’t Cry had unnerved me since its release. Like many viewers, I knew to expect Brandon’s murder and the abjection, intimidation, and violence that preceded it. But while most of the violence comes from those fictional others in the social world of the film, gender malevolence also comes from the film’s plot, particularly the romantic recuperation of Brandon as Teena in a late (and short-lived) rendering of his and Lana’s love affair as a lesbian relationship. This is particularly visible in the surprising, even perverse, love scene that follows Brandon’s rape. “Were you a girly girl, like me?” Lana asks Brandon, as he props himself up on one elbow and she gently removes his shirt and the Ace bandage strapping down his breasts. “I don’t know what to do,” Lana continues. It is her first declaration of sexual inexperience (despite earlier love scenes), and thus becomes a self-conscious reference to the specifically lesbian sex Lana has never had but is about to, with Brandon as a girl. The scene affirms what Brandon’s rapists had imposed (while reclaiming him later as their “little buddy”)—that Brandon is female. While other moments of sex-gender uncertainty or even duplicity are contained by the plot (when, for example, in order to explain biographical inconsistencies and his illegally assumed identities, an incarcerated Brandon tells Lana he is a hermaphrodite), it is disturbing to watch Brandon be recovered by the script into a love that refuses the masculine gender he has struggled to become and for which, indeed, he is finally killed.

As Judith Halberstam suggested, however, the conventional romantic style of the scene may work for those audiences who would prefer to receive Boys Don’t Cry in its universalizing, promotional terms—as a tragic love story between two people (Lana, and especially Brandon) who sought personal truth (Halberstam 2001), a gesture familiar and even necessary among commercial protagonists, whose transgender version had also appeared in Neil Jordan’s The Crying Game (1992) and would be richly reborn on television in Frank Pierson’s Soldier’s Girl in 2003, and whose gay male version would hit the 2005 A-list with Brokeback Mountain.

To be fair, first-time feature director Kimberly Peirce and her colleagues had a complicated artistic task on their hands in bringing history and license to Brandon’s volatile biography. But perhaps especially in fiction films based on true stories, license is the blessing and the curse that provokes ideological questions (and culturally telling answers) about events excluded and the terms and conditions of those left in. The most pointed exclusion in Boys Don’t Cry is Phillip DeVine, the young African American man who had been dating Lisa Lambert (renamed Candace in the film), who was killed alongside Lisa and Brandon by John Lotter and Tom Nissen in Humboldt, Nebraska in 1993 (an exclusion Peirce referred to in a National Public Radio interview as a subplot she just had no room for). But also troubling for me, alongside the unsettling “lesbian” scene, is the extravagant coherence of the film’s class-cultural overlay. In Boys Don’t Cry, working-class life does not cause transphobic murder, but it does overdetermine it in ways that we need to understand more deeply.

My reading of Boys Don’t Cry through the lens of class representation is not born of a search for so-called positive images, but I wince at the repetition of popular images of working-class pathology. Whatever may have been the circumstances of citizens in Falls City, Nebraska, in Boys Don’t Cry everyone is trapped by limited options in a limited place, by duplicity, by histories of violence and a lack of autonomy, by single motherhood, by numbing and underpaid work (“You don’t have to be sober to weigh spinach,” Lana tells Brandon), by drinking too much and thinking too little, by rosy, unrealistic images of the future, by a destructive impulsiveness and, in John and Tom’s case, a murderous rage born of its own history of psychic torture and incarceration. “Cutting,” Tom explains (displaying the self-inflicted knife wounds on his calf), “snaps me back, lets me get a grip.”

None of these conditions is intrinsically the stuff of working-class life, and each might be understood as a stereotype of some other social form, including youthful immaturity and self-destruction or a regional culture that imposes conformities and distrusts outsiders. But dramatized together, such conditions become the very scaffolding of working-class sensibility in Boys Don’t Cry, a gothic, elemental portrait of a community whose citizens are rarely able to act on their own behalf and that finally ends in deadly events.4

My response to this image is not recuperation, a wish for a nobler portrait of thoughtful and hard-working people, among whom a few bad apples wreak havoc and commit murder. The conditions that define life in Boys Don’t Cry exist and have provoked recognition for many viewers and critics. Those viewers might be more offended still by a “condescending glamorizing” of working-class subversiveness amid the deprivations and cruelties of poverty, or by working-class images burdened by an expectation of stoicism or grace.5 But the gothic shorthand, like its flipside narrative of class transcendence, diminishes the human complexity of how and why people act as they do—good and bad—in conditions of privation, exclusion, and rage. In Boys Don’t Cry, when Brandon shows a photograph of Lana to his cousin Lonnie and asks, “Isn’t she pretty?” Lonnie responds, “Yeah, if you like trash.” It is a moment when the film makes explicit what it has suggested from the first few frames—a bleak landscape populated by “white trash” (whose racialization may partly explain why there was no room for DeVine as subplot). As the story unfolds, events known from the historical record become outcomes predicted by class pathology for an audience of cultural consumers too primed for such a judgment and too attracted by its gritty and exotic brand of realism.

But that is not the whole story. Within this universe of feeling and reaction, structured by lack and tinted blue by country lyrics and a protective and threatening nighttime light, characters fuse gender and class through their longings for love, acceptance, and a better life. For Candace and Lana, Brandon’s charm and attentiveness outweigh his ineptitude in such hypermasculine rituals as bar fights and bumper skiing. He is a different kind of man—radiant, beautiful, clear-skinned, and clean, the promise of masculinity and mobility beside Tom and John, who stand instead as scarred and mottled failures. They are condemned to prison and poverty, while Brandon and Lana aspire to adventure and romantic escape, however unlikely their plan of karaoke for pay. Brandon’s gender-passing, moreover, is anchored in a self-promoting tall tale of class status, with a father in oil and a sister in Hollywood—an erasure of his hustling and criminal evasions made plausible by his angular, unhardened, boyishly feminine good looks. Even as Lana’s mother (Jeanette Arnette) calls him over to inspect his face more closely (while Brandon and the audience hold their breath), the judgment is splendor, not duplicity, though that judgment will not save him when his passing is discovered and his shame and vulnerability are redoubled by gender and class exposure.

Lana’s mother inspects Brandon’s face, Boys Don’t Cry © 1999 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation.

Received by others as a young man, Brandon’s “pussy” masculinity embodies hope for romance and social mobility, and his careful observation of others’ gender style becomes reflexively thoughtful, in contrast to John’s brutal reactivity and Tom’s copycat impotence. Exposed as a sex-gender trickster, those same qualities make Brandon fair game for the violent reenactment of normative gender difference and hierarchy.6

My interest in the articulations of class and gender in Boys Don’t Cry and my anxiety about the film’s supersaturated typifications of working-class fate speak to the reentry into cultural studies of class belonging and representation. As Sally Munt (2000) charted so clearly, cultural studies began with a leftist commitment to working-class inclusion and liberation, a commitment later challenged for its inattention to other axes of social difference and power. In the 1990s, class cultures in Left terms were pushed to the rear-ground even as class difference continued to operate and to make itself felt. As a cultural studies of class renews itself, it does so conscious not only of the historical reproduction of class position and the persistence of exploitation and struggle, but also of the complex trajectories of class location and identity that occur within the lives of persons and populations. “We tend now,” wrote Cora Kaplan in 2000, “to think of class consciousness past and present more polymorphously and perversely: its desires, its object choices, and its antagonisms are neither so straightforward nor so singular as they once seemed” (13). Here Kaplan expresses a queered form of class analysis to which my comments on Boys Don’t Cry respond, an analysis that not only connects class to (trans)gender and sexuality but also articulates the complexity and recursiveness of the category and its variants. Class cultures are produced not least by popular representations, and complexly so, in contexts where class life is sometimes central, other times not, structured and structuring in critical but incomplete ways.

Pressed to identify the primary representational and political terms of Boys Don’t Cry, I would call the film a transgender story. Pressing further to the layered conditions of social life takes me to the film’s class character. That kind of pressing on, reading queerness for class and class for queerness, exposes the availability and malleability of shaming and excess in pathologizing queer and class others. Shame and excess are essential to suturing and even interchanging the categories of queerness and class, a substitution often accomplished by means of violent exposure. The rumble of popular surprise and anxiety about Jaye’s revealed penis in The Crying Game (1992), for example, can still be felt in Boys Don’t Cry. As working-class club performer and transgender woman, Jaye suffers many of the same impositions as Brandon, but she survives, disoriented, brutalized, and stripped of feminine glory and power. Here, too, shame and excess are rapid infusers of cultural hierarchy, at work in commercial image and everyday expression and equally at work in the move out of shame into respectability and status. That’s the trade: a superabundance of queer and class shame for the mean distribution of status and regard, some spared and others sacrificed over and over again.

![]()

2

Queer Visibility and Social Class

In his beautiful essay “Intellectual Desire,” Allan Bérubé (1997) disentangles a lifetime of border living and territorial and symbolic migration. Growing up poor of French Canadian descent in the United States and surviving the shame and hostility rained down on his speech community, his family’s Catholic religiosity, and their position and culture in the working class, Bérubé came out as homosexual and intellectual in conditions that predicted neither but courted both. A consciously bookish kid, he read, and envisioned “a different world, full of poetry, literature, great music, philosophy, and art” (52) through the Encyclopedia Britannica volumes purchased from the door-to-door salesman in his family’s trailer park and the classical records his parents played on a hi-fi his father had constructed from a DIY kit.

Amid his father’s job relocations, brief periods of middle-class surroundings, returns to the family farm, and permanent economic struggle following the unsuccessful strike of his father’s labor union, Bérubé’s family endured the historic uncertainties of striving, achievement, and loss—liminal states that mark so many personal and community narratives (even happy ones) of class and other forms of mobility in the United States. Lovingly, and nostalgically, Bérubé traces the reciprocities of class, sexuality, language, ethnicity, and region, writing first to an audience of queer conferencegoers in Montreal, a city he had never before visited in a province from which his family had hailed a generation before his parents. I attended that conference (“La Ville En Rose,” November 1992) and, like so many others in the audience, was riveted by Bérubé’s warm invitation to imagine queerness through the sociocultural kaleidoscope of class migration. In his talk, he made no appeal to a uniform definition of social class or even a stable if multiform one; instead he spoke of a writerly model of narration and identification that exposed class experience at the historical conjuncture of many things: money, labor, desire, opportunity, alliance, displacement, education, and the stabilities and instabilities of privilege.

Neither Bérubé’s story nor his title, “Intellectual Desire,” is a likely candidate for production at NBC or Showtime—outlets that typically require more glamour and less anxiety, more triumph and less uncertainty, and more humor and less loss to cultivate a favorable narrative environment for the sale of cars and cruises and to sustain the right audience of middle-class gay and straight consumers and subscribers. Bérubé’s story is also openly attentive to questions of class desire and instability, a discourse many critics claim to be missing from U.S. popular culture and especially from the commercial media, bound as those media are by the transparency of middle-class norms like American dreaming and upward mobility.

Why, then, do I lead with Bérubé in a chapter on the class markers of queer worth in contemporary commercial media? Because his essay reminds us that the forms of distinction, pleasure, and injury that make up the cultures of class run unevenly through a range ...