![]()

Chapter 1

Success or Failure?

Minnie Goldstein (Mashe)

b. 1882, Warsaw, Poland To U.S.: 1894; settled in Providence, R.I.

Minnie Goldstein’s struggle to achieve basic literacy was a difficult one. In her native Warsaw, Goldstein (fig. 4) spent most of her time on the street, and in New York she went to work as soon as she arrived at the age of twelve. She never received any formal education. Only as an adult did she learn to read and write, first Yiddish and then English. Although she asks the scholars at YIVO to judge whether she has been a success or a failure, Goldstein clearly believes she has been a success. Starting with virtually nothing, she has acquired several houses, learned how to read and write two languages, become active in communal affairs, and “fooled the doctors” by virtually curing her son of the debilitating effects of polio.

My parents and I were born in Poland. I am a sixty-year-old woman. I have always liked to dress neatly and cleanly. I love to take long walks in the fresh air. In the summer I love to bathe and swim in the ocean. People tell me that I do not look older than forty-eight. My mother brought me to America when I was twelve years old. I was married in America.

As far as I recall, my parents and their parents were all natives of Warsaw. I was born to respectable parents. My grandmother and grandfather had a large business in Warsaw. They had a wholesale shoe and rubber business on Nalewki Street, which was the biggest business district in Warsaw at that time. I found out that my grandmother came from a family of poor workers, and that her parents had died very young leaving her as a young orphan with a little sister. At the age of twelve, she went to work in a shoe business as an errand girl, and there she stayed until she worked her way up to become a saleslady. Then she opened her own shoe store. She got married, but always remained a businesswoman. Though she did not have any education, she knew how to pray well and was very pious.

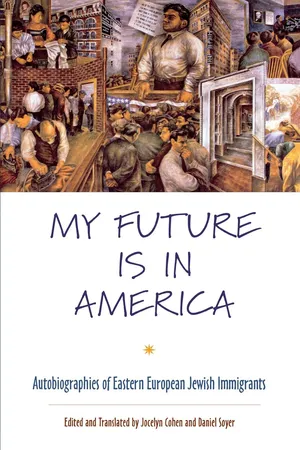

Fig. 4. Minnie Goldstein. Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

My grandfather came from a very respectable family, but his parents had become very poor. My grandmother’s business went very well. Together they had twelve children, but their children did not live long. Of all those children, only my mother survived. The rebbe* advised my grandmother to have my mother raised in a poor household with many children, until she got older. And when my mother became older, her mother brought her home and told her that she (my grandmother) was her real mother. Their house was always empty. Only the servant was at home, while the mother and father were at the store until late. My mother felt terribly lost.

Well, the time came, and my mother married a yeshiva* student. She had a dowry, and it was agreed that the groom’s parents would provide the couple with board. But before long she gave birth to two children in two years and her husband became sick and died. My mother was still very young, all of nineteen years, when her first husband died. When my mother married my father he was a young man of twenty, also a yeshiva student. Since my mother wanted to take care of her children, she lent out the money that she had from her first marriage as a first mortgage on a house. Her father-in-law said that he wanted to keep his son’s children, since she was marrying again. Her father-in-law also had a second mortgage on the same house, and was the children’s guardian. When property fell steeply in value, some sort of deal was made, and the house was sold at auction. In short, the children’s grandfather received the money that belonged to the children and then sent the children to my mother.

My parents were always physically weak people. My father saw that it could not go on like that for too long—taking board from my grandmother and warming the bench studying. So he started to rent out houses and my grandmother took in one of my mother’s children. My mother also bore my father two children—my brother and me.

Time passed. My father’s business did not go well. My grandmother continued to help but it helped like a hole in the head. My parents were not making a living. Then my grandfather died, leaving my grandmother alone with her first grandchild, a young boy. For as long as I can remember, there was always worry in my parents’ house when I was a child—that there was no rent money … that times were bad—until my grandmother convinced my father to open a kind of a little shoe business. Nor did this bring in any fortune. Then my grandmother said to my father, “Bring the goods from your business and we’ll work together.” But her business was not going so well either.

Well, they became partners, and things went a little better, but this did not last long. My half-brother felt that he would have been much better off if my father had not been a partner, and he convinced my grandmother that the business was going under. Arguments started. My grandmother yelled, my mother cried, and my father kept quiet. I once heard my mother say that she was certain that merchandise was missing from a couple of crates in the store. But my father said, “Oh, don’t talk nonsense.” More time passed and the arguments and crying continued. Once, around two o’clock at night, I heard my mother say to my father, “Hershl, please, let’s get dressed and go to the store. I’m telling you, my heart tells me that my son and my mother are removing merchandise.” Well, they went over and actually found them carrying merchandise from the store. Well, my father immediately left the partnership with my grandmother and tried it on his own. But again it did not work out. My grandmother still had to help us with a couple of dollars a week.

Suddenly, my mother noticed that my father was walking around with a small book in his hand. He was walking back and forth, reciting from the book in English and translating into Yiddish: “Good morning, gentlemen. Gut morgn, here.” He walked back and forth, learning the words. So my mother asked him, “Tell me, what do you need to know that for?” My father kept quiet, but he never failed to learn a couple of words each day, until my mother insisted that he tell her what he intended to do and why he needed to know English words. Then he told her that he was getting ready to go to America.

“What are you talking about? You’re going to America? You’re a weak-ling and you don’t have a trade. And you don’t have any money. Who goes to America anyway? Those who run away from home because of some sort of crime, or those who are banished there by the government. What does someone like you have to do with America? They need only heavy laborers there and you can’t do anything.”

“Well, that’s exactly what I want. I want to go to a country where heavy labor is no disgrace. I want to go to a country where everyone is equal, where the rich also work, and work is no disgrace. I want to go to America, where a Jew does not have to take off his hat and wait outside to see a Pole. In other words, I want to go to a country where I can work hard and make a living for my wife and children and be equal to everyone.”

Well, no matter how much my mother tried to convince him that, since there was no one from their family in America, he would have no one to turn to for money, it did no good. He went on with his English dictionary. And one morning at about four o’clock, there was a loud knock on the door. I heard my father say to my mother, “Brayndl, dear, the coachman is here. I have to go.” Well, I do not remember whether my mother accompanied him to the train, but I think that he left by himself. In the morning, my mother told me that if anyone asked me where my father was, I should say that I did not know. My mother said that she would tell strangers that my father had gone abroad on business, because she was very ashamed that her husband had gone to America.

My mother’s name was Brayndl. My Father’s name was Hershl. My mother was something of a nervous and excitable woman. She would often yell, and sometimes also curse. But my father often said that she was a stunning woman. My father had a very refined outlook. He was someone who was happy with whatever came his way. He used to tell me, “My child, if you look upward, you’ll never be happy. But if you look downward, you’ll see it can be worse and you’ll always be happy with your life.” He did not like people who were proud of their money or of how smart they were. He was a quiet, honest, sincere person.

Well, my grandmother had by now kept my mother’s first two children —a son and a daughter—for a long time. And now that my father had left, she also took in the third grandchild—my real brother—and gave my mother five rubles a week on which to live. My mother rented a room from others for herself and for me. My grandmother and mother often fought. My grandmother screamed, “What do you want from me? I’m keeping three of your children, and I’m giving you five rubles a week! I am an old woman! With your two weddings and with me giving you money every week, you’ve already cost me ten thousand rubles!” My mother cried and yelled, “Who asked you to give me a yeshiva student for a husband?” My mother and I lived far away from my grandmother.

Now the bitter years of my childhood began. I remained alone in the room with my mother. No one even spoke of sending me to learn to read or write. My mother was always nervous and angry. She was very tired of staying home. She kept talking about how my father had gone away, about how she had trouble with my grandmother, about how her eldest son had betrayed her. This was why my father had no choice but to go to America. I was then around ten years old, but I understood my mother’s and my situation as though I were a girl of twenty. Well, my mother could not stay in the room; she kept wandering around, leaving me two or three groshns* each day to buy a roll with some stewed plums, which was called povidle in Warsaw. I ate rolls for breakfast and dinner, and again for supper also, because my mother came home when I was already sleeping. And if I felt like a snack, I would buy a piece of candy for one groshn, but then I would have to eat a plain roll. I was always hungry. Now who was it who said that hunger is stronger than iron? I fell upon a plan. I started to walk through the streets and whenever I saw a piece of pear or apple that someone had thrown away without finishing, I would pick it up and eat it.

When I was a child I looked a lot older than I was. I loved to play with children who were much older, and this got me in a lot of trouble. I recall my childhood boyfriends and girlfriends saying to me, “Come, let’s go to a far away street. You’ll go up to a coachman and tell him that you were sent to call a coach, and we’ll all get in and take a long ride. And when we tell him that we’re going to call the man who needed the coach, we’ll run away.” Well, they really did run away, but I got caught and the coachman brought me to my mother and I got a good beating.

Another time, several children said to me, “Mane, come with us to the marketplace (the marketplace near the Żelazna Brama—the Iron Gate). We’ll pluck the cherries off the sticks there, so we’ll have cherries to eat and a couple of groshns as well.” Well, this looked to me like a good business, because we got a job there. I heard the market woman tell my girlfriends, “I’ll give each of you two groshns, but don’t nibble on any cherries!” Well, I sat down and got to work, and I noticed that my friends were putting cherries in their mouths whenever the woman went away for a moment. Well, I was so hungry that I thought to myself, “I’ll just take one cherry so my mouth stops watering so much.” Well, the woman caught me putting the cherry in my mouth, and she grabbed me by the shoulders and looked me straight in the eye, and said to me, “Come here, you little thief. I saw it in your eyes right away—that you are a thief. You’re not getting a groshn. Now go!” That woman still appears before my eyes. Right then and there I made up my mind never again to take anything that did not belong to me.

Well, I wandered around like a lost soul. My father wrote letters with very bad news. And when a couple of weeks went by without my mother having received any letters from him, she could not sleep at night. Since she was very pious and had read somewhere that children had the power of prophecy, she kept waking me up and asking me to tell her if a letter from my father was coming for her. As young as I was, I still understood her position and I sympathized with her more than I did with myself. I was always very good to her. It happened once that I told her that a letter from my father was coming and that she would get it in a couple of days. And that is really what happened: She got a letter from my father! From then on I had no nights either, and I became so sleepy that I could not keep my eyes open. So she took spit and rubbed it on my eyes so that I would wake up and tell her when she was going to get a letter from my father.

My mother came home very sad one night, sat down next to me in the room, and started to weep and wail so hard that I too started to cry and wail. But she did not tell me why she was wailing like that, and I was so scared that I will never forget it. In the morning, my mother could not get out of bed. She spit up half a glass of blood. To this day, I do not know what she was crying about. Had she had a run in with my grandmother? Or had my father written her about his bitter situation? (This was when my father had already been in America for two years.) I heard my mother say that my father was not even making enough to feed himself, so what was he staying there for? He should come home!

My father had sold everything he could to get a couple of dollars to go to America. And when he arrived in Castle Garden,* he had two dollars in his pocket. A representative of the Hakhnoses Orkhim* brought him there. (I think that this organization is now called ORT.*)1 They gave him something to eat and a free place to stay at night, with the right to go out and see people and come back. But it was only for a couple of days. He had with him a long cloth coat with a fur collar and lining which he had received from my grandfather as a wedding present. First he sold that coat for a couple of dollars. Then he found lodgings with a family with children on Hester Street. The apartment consisted of a bedroom and a kitchen. The children slept in the bedroom with the husband and wife, and my father slept in the kitchen with three other boarders.

At first, my father was eager to learn a trade and started to learn to be a shoemaker. But after he had worked for a couple of days, the boss came to him and said, “Mister Hirsh, don’t knock yourself out for nothing. You’re not suited to the work. You’re too slow. Your hands are too clumsy to be a shoemaker.” So he left that trade and tried another trade. But the same thing happened. The boss sent him away again. It went on like this for two years. My mother kept on writing him that he should come home, but he replied, “I promised myself that I would never set eyes on Warsaw again, and I’ll keep my word.” But it went so bitter for him here that he was living on one dry roll a day. And no one knew, because he was not the sort of person to complain and did not know the meaning of the word “borrow.” If there was no money, one simply did not eat—until an idea occurred to him. He took a wooden box, bought some baby shoes, took up position on Hester Street, and sold the shoes at a profit of five or ten cents a pair. Gradually, he started to make a profit, and wrote my mother much better letters.

Before very long the women of Hester Street found out that my father would sell them a pair of shoes for thirty cents, while they had to pay fifty cents in a store for the same pair of shoes. Well, he started to earn some money, so he rented a small store. This was on Hester Street, between Essex and Ludlow. It was in an alley between the houses, which was closed off in the evening. My father put up a tent outside the store, with various children’s shoes. As soon as he had arrived in America, he had taken out his first citizenship papers. Now he started to do business and felt fortunate with his success. He started to write to my mother that she should come with me to join him in America.

Then trouble started up again at home. My mother went around anxiously and kept complaining to me, “What does your father want from me? Do I have the strength to withstand the strain of traveling to America? What good will a person like me be there, when I can’t even wash out a glass? And how can I leave behind my aged mother, who is over seventy years old, and my three children?” (My half-brother and half-sister were already married.) By then, my father had already started to send some money home to my mother. My grandmother also gave my mother money weekly for as long as my mother was in Warsaw, and I had to go pick it up every week. When my grandmother saw me coming, her blood ran cold. She saw me as a nuisance, which I could not understand. “Why is grandmother so angry when she sees me coming?” I felt that if my mother was sending me for the money, she must certainly have it coming.

Well, my father had been in America for four years before my mother decided to leave my brother behind with his grandmother and go with me to America. And then another pack of troubles started for me. My mother knew a woman who traded in silks in Germany. The woman bought merchandise in Warsaw, and she and my mother agreed that since the woman knew how to do these things, she would smuggle us over the border. The woman had already made an agreement with the conductor on the train, and she told my mother what to say when the conductor came up to her. But my mother got so scared when the conductor came up to her that she said everything all wrong. The woman started to tremble as if she had the highest of fevers. When we got off the train, she asked my mother, “How can a woman like you undertake such a long journey?” But we traveled on.

We said goodbye to the woman and arrived in Berlin very early...