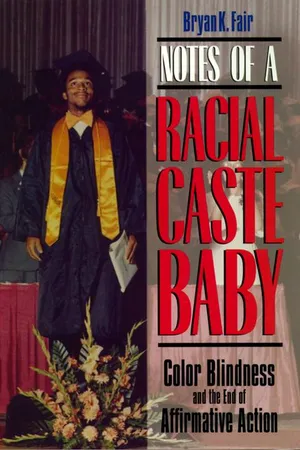

![]() PART ONE

PART ONE

A PERSONAL NARRATIVE![]()

NOT WHITE ENOUGH

I have lived in Ohio, North Carolina, California, and Alabama. In each place, most blacks, whites, and other minorities live separate lives. Most blacks are poor and live in isolated, self-contained slums. They attend segregated schools that are poorly funded, overcrowded, and in need of repair. Most whites live away from them, in other sections of the cities or in the suburbs. Most of them attend better-funded, less crowded, newer schools. Other racial enclaves buffer or border those of whites and blacks. Daily contact between whites and blacks is limited, except in employment settings where whites supervise blacks. Social clubs and churches are often hypersegregated. Residential property values seem to be driven by racial demographics, with the degree of whiteness in the community in proportion to the price. Each community has its own consumer services, whose quality varies with the community’s color.

Similar patterns prevail across the United States. Even the poorest whites and blacks live separately, suggesting that economic status alone does not explain housing segregation. Yet in most of the country, I hear barely a whisper publicly about these differences in the lives of whites and blacks. Behind closed doors, however, racial groups hurl epithets and accusations. How did Americans arrive at this state? Is there something peculiar about blacks that locks most of them in America’s ghettos? Are white folks responsible? Is there anything Americans can do to eliminate racial caste? I want to answer these questions in light of my own experiences.

I was born in Ohio. Even though this state was not organized as a slave state, its early judicial cases indicate that by law, whites had numerous rights that blacks and mulattoes were denied. The Ohio constitution restricted voting privileges to white males, and its statutes limited common schools to white children. When a white person was a party in a case, blacks and mulattoes could not be witnesses, and they also could not serve on juries.1 Presumably, most Americans today would admit that such policies were racist and unfair. Nonetheless, Ohio is not generally thought of as a racist state, at least not in the way that many Americans view, say, Mississippi or Alabama. Indeed, many communities outside the South are seen as free of the racist tradition that defines the South for many non-Southerners. This assumption makes the South—specifically a place like Alabama, where I now live—appear worse than it is, and the rest of the country better.

But is this reputation deserved? Long before I was born, Ohio had relegated most blacks to caste by law and custom. Many early judicial cases in Ohio were brought by parties claiming some proportion of white blood, which, they insisted, entitled them to all the privileges of whiteness. For example, Polly Gray, who appeared to be “a shade of color between mulatto and white,“ had her robbery conviction reversed because the trial court had permitted a black witness to testify against her in violation of state law. The appellate court found that a person “of a race nearer white than mulatto . . . should partake in the privileges of white.” In another case, the court had to determine whether the children of an all-white mother and a three-quarters white father were white under the law. The court held that because the term white described blood and not complexion, the children were white.2

Other cases in the Ohio courts focused on whether those having a mixture of any blood other than that of “entirely white” persons could vote. The courts ruled that all persons nearer to white than black were entitled to enjoy every political and social privilege of the white citizen. Monroe v. Collins is a good example. In this case, the Ohio Supreme Court examined the constitutionality of a state law assigning to elected judges the duty to question any person with a distinct and visible admixture of African blood who was trying to vote under state law, about his or her age, place of birth, parents’ marital status and whether they had African blood, whether in this person’s community he or she was classified and recognized as white or colored, and whether his or her children attended schools for white or colored children. The court found the statute to be unconstitutional, not because the vote was denied to blacks, but because persons nearer to white than black were denied their constitutional right to vote. Many similar cases required judges to decide the rights of fugitive slaves who had fled to Ohio, the rights of their alleged masters seeking their return, or the criminal liability of those who aided the fugitive slaves’ escape.3 The judges accepted what they believed was their legal duty: to determine whether Ohioans were white enough to enjoy various rights or privileges.

Van Camp v. Logan4 best describes Ohio’s early race rules. A divided state supreme court held that Enos Van Camp’s children—who were three-eighths African and five-eighths white and who appeared and were generally regarded as colored—were not entitled to go to the white children’s schools, notwithstanding prior statutes and judicial opinions to the contrary. This case indicates the elusive meaning of whiteness; that is, in the middle of the nineteenth century, the meaning changed.

According to Judge William V. Peck, before 1848, no law in Ohio provided for the education of any but white children. Then in 1848, Ohio law for the first time provided for the education of colored children, directing a tax for that purpose to be levied on the property of colored persons to support separate schools for them. This statute proved ineffective, however, because it did not generate sufficient money to fund a separate school, and Ohio continued to refuse to divert any of the common school funds to educate colored children.

In 1853, the Ohio legislature repealed this earlier statute, replacing it with one that maintained racially separate schools but gave colored youth their full share of the common school funds, in proportion to their numbers. But when the village of Logan did not maintain a school for colored youth, because of insufficient numbers, the court found nothing illegal, declaring that it was a matter for the legislature, not the judiciary.5

The court’s divided opinions contain a revealing exchange among the judges regarding what the Ohio legislature intended when it used the term colored in the 1853 statute. The majority held that the term was used to create two classes, white and colored, thereby changing the problem from the proportion of white blood to the presence of any nonwhite blood. Based on this reasoning, a person was either entirely white or colored. The court used Webster’s dictionary to define colored:“black people, Africans or their descendants, mixed or unmixed.... A person having any perceptible admixture of African blood, is generally called a colored person.” The majority therefore decided that the 1853 statute was intended to place in one school all the white youth and, in the other, all who had any visible “taint” of African blood.6

Judge Milton Sutliff, for himself and the chief justice, wrote in a bitter dissent that “caste legislation is inconsistent with the theory and spirit of a free government, asserting all men are created equal.”7 He concluded that prior constructions of Ohio law precluded the decision reached by the majority. But Sutliff was unwilling to extend the disabilities assigned to colored youth any further than those that had been applied to blacks and mulattoes—an emphasis on caste legislation that presaged the writing of John Marshall Harlan at the end of the nineteenth century.

While I was growing up in Ohio, I never learned anything about its racial history or its traditions of racial privileges for white Ohioans. None of my teachers mentioned that Ohio law had given precedence to whiteness. We never discussed why schools were segregated in the first place or why white parents did not want their children to attend schools with black children.

Logan and similar cases throughout the country were used to construct the meaning of being white, that is, a person without the “taint” of black blood. Whiteness was defined in opposition to blackness; in short, whiteness meant nonblack.

Contemporary writers criticize modern remedial affirmative action as a racial spoils system. But this system was established in places like Ohio in the early 1800s when legislatures and courts were claiming that white blood was somehow better than black, thereby entitling whites to privileges denied to blacks and other Americans of color. This, of course, is the essence of white supremacy: the presumption that white blood or whiteness is, by some unknown measure, better than other blood or racial identities.

Notice the circular logic here: whites receive privileges because of their special blood, and since they receive privileges like education, employment, and voting, they are superior. If whites are superior, then nonwhites—namely, blacks—must be inferior. Racial superiority, then, is a social construct too, a myth created to express certain beliefs and acts.

If there were no such thing as white blood, would there then be no such things as white and black? Was James Baldwin correct when he wrote “color is not a human or a personal reality, it is a political reality“?8Is it possible that racial blood groupings were devised to allocate benefits to select Americans? As Ian Haney López writes, “Put most starkly, law constructs race.” 9

I wish I could state that these concepts—whiteness and white superiority—were nothing but flimsy houses of cards, but even if this were true, it would not change America’s current political reality. As Cheryl Harris argues, the law’s construction of whiteness defines and affirms critical aspects of white identity (that is, who is white), of white privilege (what benefits accrue to that status), and of property (what legal entitlements arise from that status).10

Being known as or appearing white has given select citizens, in Ohio and elsewhere in the United States, political and economic advantages over blacks, mulattoes, and other colored persons, as well as poor whites, especially white women. Successive generations of whites have accumulated and passed down wealth derived in part from racial privilege. In turn, these advantages have placed persons who were not known as or who could not pass as white into a racial caste. For them, white privilege meant deprivation, little wealth to accumulate or pass down. White supremacy denied them equality of opportunity, destroyed their families, and relegated them to enclaves of despair. In American neighborhoods today, the results of racial privilege for whites and racial caste for blacks and other racial minorities are evident. The United States today is at least two nations.11

For Ohioans of color, the law has not been color blind; indeed, color determines status and rights; it means everything. Some of those colored folks who could not pass as white Ohioans were my dark brown ancestors who migrated to Ohio from Virginia and West Virginia at the beginning of the twentieth century, barely a generation from American slavery. My maternal great-grandmother, Julia Clay Woods, moved from Talcutt, Virginia, to Columbus with her five children: Faye, Gertrude, Sadie, Bessie, and Alexander, my grandfather. Victoria Smith Casey and Pank Casey, my other maternal great-grandparents, moved their twelve children from coal-mining company towns in Bluefield and Wyco, West Virginia, to Columbus. Their daughter Elizabeth Casey married Alexander Woods. My maternal grandparents had four sons and one daughter: Alexander, Jerry, Ralph, Earl, and my mother, Dolores.

![]()

DEE

My mother, known as Dee, was born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1929, the oldest of five children, in the midst of the Great Depression. The crash of the stock market was only a prelude to a general collapse of the American economy. As many as fifteen million Americans were unemployed, and the national income dropped by more than 50 percent. Farm prices fell nearly 60 percent, and business failures and mortgage foreclosures led to the failure of more than five thousand banks. Congress and President Franklin D. Roosevelt responded with sweeping federal legislation to rescue the economy and to protect industries and workers from financial ruin and starvation. After the Depression came World War II, also requiring the guidance of a strong national government.

Neither President Roosevelt’s New Deal nor the war effort was color blind. Consequently, blacks living through those crises had to contend not only with economic insecurity but also numerous forms of racial discrimination and violence. For instance, relief payments for blacks were often several dollars less than those for whites, and blacks did not receive the same employment opportunities as whites did under the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Black servicemen, regardless of their education or experience, were forced to live in segregated facilities and serve in segregated units. In fact, many felt freer when they were overseas than when they were at home. And the federal government’s economic bailout from the Depression did nothing to eliminate racial caste in the United States.

Dee’s father, Alex, was a chauffeur and janitor. For a brief time he worked in the WPA. Her mother, Elizabeth, cooked in restaurants. During World War II, she worked with other women at the War Depot, but their jobs were returned to men when the war ended. Even though neither of my grandparents was lazy or held unacceptable values, their economic opportunities were restricted by educational and employment policies favoring whites.

In 1950, my mother married Sylvester Eugene Fair. Like Dee, he was tall and striking, with a rich, dark brown complexion. He worked in the railroad yards in Columbus. They had two children, Butch and Theresa, but then divorced in 1952. Dee never remarried. By 1965, she had eight more children: Sheila, Bettye, Jayme, Duncan, Kimberly, me, Mark, and Brett. All of us took my mother’s married name, Fair.

I do not remember many of Dee’s jobs. She worked in grocery stores and bakeries, but mostly in restaurants and bars. She complained all the time about her jobs, how hard the work was and how little she earned. Sometimes when she disagreed with an employer, she simply quit and started looking for another job. She changed jobs frequently, sometimes working both during the day and at night. When she was working at restaurants and bars, she did not get home until after midnight, and so my older siblings were in charge. With so little supervision, I came and went as I chose, staying away from home as much as possible.

Sometimes I went to work with my mother and helped her wash glasses, clean bathrooms, or scrub floors. The bars were all the same: dark, smoke filled, and dilapitated, with a juke box, a cigarette machine, a small pool table, and an old, overused kitchen. Men and a few women came and went throughout the day. When I finished my work, I played pool or listened to the juke box and watched Dee’s interactions with the customers.

Dee often had to work alone, serving drinks, cooking, and cleaning. She usually prepared a daily special, such as fried chicken, pork chops, or meatloaf, accompanied by vegetables and white bread. Occasionally, she cooked pig’s feet or chitterlings. The customers loved Dee’s cooking. Nobody had her ability to make food look and taste exquisite, at least not anyone working on Mount Vernon Avenue or Long Street. I had seen her work miracles with food at home. She made meals from almost nothing and could make bologna or beans and wieners seem special.

I remember how easy it was for Dee to make conversation with her customers. A few of them were friends that came to our home, but most lived and worked nearby and frequented the bar or restaurant. She didn’t treat any of them as strangers. They talked about local news or politics, as well as the latest stories from the Call & Post, the black newspaper. She asked about their work or families and listened to their stories. Some were in between jobs or recently divorced. Others were sick from high blood pressure or sickle cell anemia. Dee was their confidante. She could console them or make them laugh. She never talked about our family or herself. As far as they knew, Dee and her family were fine. I remember being surprised by her kindness and sensitivity because at home she seemed like a different person.

At home, the demands on Dee as the breadwinner for our large family caused enormous stress. At times she worked several jobs at once, but none of them paid more than the minimum wage plus tips. She never had enough money to pay our bills. The warm, friendly disposition that I observed when Dee worked rarely appeared at home. Instead, conversations were short and pointed: “No, I don’t have any money!” or “Tell the landlord I’m not home!” Scraping together barely enough to survive took its toll. Her ten kids were an overwhelming burden. I don’t know whether she was ashamed of our poverty, but she often seemed very unhappy at home. I noted her vastly different personalities and hoped to emulate the one from work.

Unlike some of my siblings, I do not know who my father is. For years when people asked about him or his occupation, I just made something up or said he was dead. I was ashamed to admit that I didn’t know because I didn’t want to be different from my friends who did know their parents. It also was embarrassing to tell lies or to explain how my mother tried to make ends meet. I couldn’t tell anyone how little we had, why I had to work so much, or why I stayed away from home. I hated my father for not caring about me and not helping my mother support me.

When I was a teenager, I had several awkward conversations with Dee about my father’s identity, but they usually ended with one of us screaming. So I decided not to ask her about him anymore, but my resolution only increased my anger toward him and Dee. Why couldn’t she tell me who he was? Was she protecting him? Would he hurt her? And why didn’t he reveal himself? Why didn’t they understand my need to know? Even though I never again broached the subject, I had to free myself of feelings of shame, and it was not until high school that I was mature enough to acknowledge that I did not know my father. I decided, therefore, that I would not lie about my relationship with my father, that I had no reason to be ashamed, that I was not responsible for the choices he made. Now when people ask about my parents, I say that my mother has been a single parent all my life.

Not having a father taught me many things. First, I didn’t want to repeat his actions. I would not have a child until I was ready, and under no circumstances would I abandon my child. Another lesson was that children need nurturing and guidance to prepare to make life’s choices. When I reached puberty and became curious about girls, I didn’t know what to do or not to do. I didn’t know what a condom was until I was sixteen, well after my initial sexual experiences at age eight. The closest I ever came to getting guidance at home was when I once overheard Dee tell one of my older brothers to keep his penis in his pants. But those words mattered little when I was pressing myself against a girl. I needed information about pregnancy, contraception, and sexually transmitted diseases, and I needed it from responsible, informed people. My not-so-much-older siblings were of little help, as we all were on our own and had to learn from experience. It’s a miracle that I didn’t get some child pregnant.

I cannot remember a time when any of the fathers of my siblings helped Dee support or rear us. Their absence made our lives much more precarious, coming on top of the general poverty and racial caste in Columbus. For us there was only Dee. She never left us. She kept us together and provided for us as best she could. The eleven of us journeyed through the ghetto, collectively and individually, a loose but strong confederation, the older kids supervising the younger ones when Dee was working.

![]()

BLACK COLUMBUS

The dangers of racial caste in America are real and growing worse. By the time I was born, in 1960, all of Ohio’s earlier official racist policies had been repealed, but racial caste remained nevertheless: inadequate food, clothing, and shelter; substandard schools, illiteracy, and high dropout rates; few occupational opportunities, two-digit unemployment figures, and poverty wages; households headed disproportionately by single working mothers and inadequate child supervision; insufficient sex education and consequent teen parenting; poor health care, exposure to harmful chemicals and toxins, and disproportionately higher mortality rates; crime, drug-related violence, and communities under siege by police who often seem unable to distinguish between lawful citizens and criminals; and racial animus in the criminal...