![]()

CHAPTER 1

A New Age Dawning

Often forgotten in the post-Hiroshima world is that the most common first reaction to the dropping of atomic weapons on Japan, at least among Americans and their allies, was not universal horror but unalloyed joy and relief. By the summer of 1945 preparations were under way for a November invasion of the Japanese home islands, an operation that had the potential to become a military nightmare. The use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki would make that invasion unnecessary. Paul Fussell, an infantryman during the war, remembered that

when the atom bombs were dropped and news began to circulate that “Operation Olympic” would not, after all, be necessary, when we learned to our astonishment that we would not be obliged in a few months to rush up the beaches near Tokyo assault-firing while being machine-gunned, mortared, and shelled, for all the practiced phlegm of our tough facades we broke down and cried with relief and joy. We were going to live.1

Freeman Dyson, who worked for the Royal Air Force Bomber Command during World War II, was scheduled to be sent to Okinawa in the summer of 1945, where three hundred British bombers (called Tiger Force) would take up the bombing of Japan. As Dyson noted, “I found this continuing slaughter of defenseless Japanese even more sickening than the slaughter of well-defended Germans.” Dyson was at home when he heard of the Hiroshima explosion: “I was sitting at home, eating a quiet breakfast with my mother, when the morning paper arrived with the news of Hiroshima. I understood at once what it meant. ‘Thank God for that,’ I said. I knew that Tiger Force would not fly, and I would never have to kill anybody again.”2

As nuclear weapons have increased in strength and number since 1945, the enormity of Truman’s decision to use these weapons has grown to the point that it is now widely considered to be the most controversial act of the twentieth century. If nothing else, it has spawned a bitter debate among historians, some of whom believe that Japanese surrender was imminent, and that therefore use of atomic weapons was totally unjustified, while others maintain that the Japanese were prepared to continue fighting indefinitely.3 Truman himself expressed no regrets about the use of atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and in a 1961 speech he responded to his critics in his inimitable fashion by observing, “I haven’t heard any of them crying about those boys in those upside-down battleships at Pearl Harbor.”4

Regardless of one’s opinion on whether or not the use of atom bombs was necessary to end the war, the fact that they were used has assumed a prominent place in modern history. Indeed, the importance of this event is now universally acknowledged (a group of sixty-seven of the nation’s leading historians and journalists in 1999 called this the most important news story of the twentieth century), but in the immediate aftermath the transformational implications of what had been wrought at Hiroshima were absorbed by Americans only slowly.5 As late as 1960 Arthur Koestler argued that humanity had found it difficult to come to terms with the Nuclear Age because “from now onward mankind will have to live with the idea of its death as a species.” Koestler compared the reluctance to accept the post-Hiroshima world to the slow, difficult acceptance of the Copernican system over the Ptolemaic.6 Vincent Wilson, Jr., also found little evidence that this much heralded new era had taken root, and even argued that “it would seem more to the point to label these past years the T.V. Age—considering the apparent impact of television on the population as a whole.”7

Even military strategists at first refused to believe that the bomb had changed anything. That a single airplane had visited such destruction on Hiroshima was impressive, but the quantity of destruction was still on a recognizable scale, such as had been seen in earlier Allied bombings. Referring to atomic weapons in the fall of 1945, James V. Forrestal, secretary of the navy, cautioned that it was “dangerous to depend on documents or gadgets, as these instruments do not win wars.”8 A few months later the Pentagon issued its first assessment of the impact of atomic weapons, and concluded that the bomb’s destructiveness, limited availability, and great expense “profoundly affect the employment of this new weapon and consequently its influence on the future conduct of war.”9

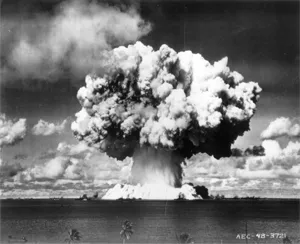

FIG. 6. The caption attached to this photograph was “Baker day—Bikini—The cauliflower aftercloud, after dumping two million tons of water, which had been sucked up by the underwater explosion, rises in breath taking wrath, July 25, 1946.” RG 304-NT-AEC-48-3721 (folder 1A), Still Pictures Branch (NNSP), National Archives at College Park, MD.

The views of the atomic pessimists seemed to be vindicated by the results of the “Able” atomic test at Bikini Atoll on July 1, 1946. The bomb was some two miles off target and sank only a few of the assembled ships. The Bikini “Baker” test of July 25, 1946, was a different story, however, and proved to be sufficiently destructive to restore the bomb’s tarnished image (see figs. 6 and 7). By June 1947 the Joint Chiefs had concluded that “atomic bombs not only can nullify any nation’s military effort, but can demolish its social and economic structures and prevent their reestablishment for long periods of time.”10

Certainly the public itself seemed initially impressed. Paul Boyer has called the first reaction to the atomic bomb “a psychic event of almost unprecedented proportions,” but has also characterized the public opinion data on the bomb for this period as “confusing and to some extent contradictory.”11 A survey conducted by the Social Science Research Council (SSRC) in 1946 found that 98 percent of Americans had heard of the atomic bomb, but of course this meant that 2 percent of Americans (some two million) remained ignorant of this revolutionary new weapon.12 The survey was also remarkable in the depth of pessimism it revealed. Two-thirds of the respondents expected another war, but three-fourths claimed not to worry about the bomb because ordinary people were powerless to address such problems.13 As the Soviets developed their own atomic weapons, American fears began to increase that U.S. cities would be subject to attack by nuclear weapons in a conflict with the Soviet Union. By 1953 the Soviet Union had successfully exploded a hydrogen bomb, and as the decade of the 1950s wore on polls registered increasing anxieties that this terrible new weapon would be used against the United States.14

FIG. 7. The Baker mushroom cloud, as it begins to flatten out. RG 304-NT (folder 1A, fig. 2.42), Still Pictures Branch (NNSP), National Archives at College Park, MD.

Still, the expectation of another war within a generation and the conviction that nuclear and thermonuclear weapons would be used against American cities did not result in increased preparations against such a calamity. By 1960, in fact, Americans by overwhelming margins had not only made no preparations for nuclear war, they had not even thought about making such preparations. In part this was because Americans believed that civil defense was properly a government responsibility rather than a private one.15 Government officials, however, often had a very different opinion. In a famous 1961 Columbia Broadcasting System program on civil defense, secretary of defense Robert McNamara proclaimed that “certainly the Federal Government, the State, and local governments all have parts to play, but most importantly, it’s the responsibility of each individual to prepare himself and his family for that (thermonuclear) strike.”16

McNamara’s statement was less callous than it might appear, given the woeful history of civil defense programs during the previous decade. During the two world wars civil defense had generally meant the marshaling of resources for the war effort rather than protection of the civilian population from attack, but by the end of World War II the development of long-range bombers and nuclear weapons had added a new urgency to civil defense in the United States. In 1948 the Office of Civil Defense Planning had characterized civil defense as the “missing link” in America’s defenses, and had called for civil defense training for a cadre of fifteen million Americans.17 This vision was not to be realized, and in succeeding years civil defense would be eschewed by the military as a civilian responsibility, shunned by state and municipal governments as too expensive, and largely ignored and chronically underfunded at the federal level. Civil defense consistently fell victim to what Thomas J. Kerr, in his authoritative work Civil Defense in the U.S., has called “the politics of futility.”18

Strategy during the 1950s

By necessity, civil defense issues were closely linked to nuclear strategy, and an understanding of overall nuclear strategy during this era will shed some light on the fallout shelter debate of the 1950s and 1960s. With the emergence of a bipolar world after World War II, the chief element in American foreign policy became the “containment” of the Soviet Union. George Kennan, head of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff, had emphasized a nonmilitary approach to containment, and President Truman himself was initially resistant to large outlays for defense. Truman also had difficulty, according to David Alan Rosenberg, in seeing the atomic bomb as “anything other than an apocalyptic terror weapon,” and one of Truman’s legacies to subsequent presidents was to establish civilian control of nuclear weapons and to make sure that the ultimate decision to use such weapons would rest with the chief executive.19

The most important strategic document produced during the Truman administration was NSC 68, a secret National Security Council study. Under the direction of Paul Nitze, who took George Kennan’s place as director of the Policy Planning Staff in 1950, NSC 68 portrayed the competition between the United States and the Soviet Union as a bleak struggle for survival. NSC 68 insisted that “the cold war is in fact a real war in which the survival of the free world is at stake,” and endorsed “building up our military strength in order that it may not have to be used.”20 NSC 68 suggested that nuclear weapons alone could not do the job, and advocated a buildup of conventional forces for an “increased flexibility” that would enable Americans to “attain our objectives without war, or, in the event of war, without recourse to the use of atomic weapons for strategic or tactical purposes.”21 While the idea of flexible response suggested by NSC 68 would largely be ignored by the Eisenhower administration, this doctrine would be revived in 1960 under Kennedy.22

During the Eisenhower era, the president and secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, sought to limit both Soviet ambitions and American defense spending. They believed that they could accomplish these goals through the strategy of “massive retaliation,” of responding with nuclear weapons to a wide range of potential international problems. While defense spending in the Eisenhower administration would remain relatively high, especially for “peacetime,” it was considerably less than many were calling for.23 Emphasized by Eisenhower throughout his administration was a buildup of nuclear forces and a reduction of conventional forces (the so-called New Look). This philosophy was reflected in America’s growing nuclear arsenal, which increased from about a thousand weapons in 1953 to nearly eighteen thousand by 1960.24 The crucial psychological aspect of massive retaliation was to convince potential enemies of America’s willingness to avail itself of the nuclear option to defend its interests. This approach was emphasized in NSC 162/2, a secret 1953 document in which strategic planners were urged to “consider nuclear weapons to be as available for use as other munitions.”25 To this end Eisenhower insisted that “the United States cannot afford to preclude itself from using nuclear weapons even in a local situation,” while Dulles observed that “the ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is the necessary art.”26

In the event of war, it would be the Strategic Air Command (SAC) that would be delivering the weapons. Actual target selection seems to have been left largely to the discretion of Curtis LeMay, commander of SAC (fig. 8). LeMa...