![]()

1

“Eloquent Reminders of Sailing and Shipbuilding”

How the Seaport and World Trade Center (Re) made Fulton Street

In 1966, as Penn Station’s debris was hauled to a landfill, historic preservation seemed to be going against the grain of Gotham’s advance. As the city expanded, it rebuilt itself every generation. Perhaps that “creative destruction” could be attributed to capitalism, as Karl Marx and Joseph Schumpeter claimed. Harper’s Magazine lamented in 1856, “New York [Manhattan] is notoriously the largest and least loved of any of our great cities. … Why should it be loved as a city? It is never the same city for a dozen years altogether. A man born in New York forty years ago finds nothing, absolutely nothing, of the New York he knew.” But that growth had been the city’s success. By 1800, New York’s population and shipping tonnage were America’s largest; its port grew with the Fulton Fish Market (1817) and the reclamation of what was to become Water, Front, and South Streets. Its launch of the packet trade to England (1819), the completion of the Erie Canal (1825), and the expansion of the city’s financial, industrial, and commercial sectors boomed it further. The port’s share of US trade leaped from 5.7 percent in 1790 to 57 percent in 1870. However, South Street’s East River traffic declined after 1865 because larger ships of steam and steel, mostly foreign owned, required the Hudson River’s deeper waters and newer terminals. Overall, New York surpassed London as the world’s greatest port by 1914. That success brought so much congestion to the narrow and ancient streets that Lower Manhattan became “an intolerable place to do business.”1

The construction of shoreline elevated highways, including the East River Drive (later, FDR Drive) was supposed to solve the problem. Begun in 1934 by Robert Moses using Works Progress Administration crews, the roadway was later extended by using ship ballast from England’s bombed-out buildings. The last section of FDR Drive, which was completed in 1954, descended to street level at Old Slip, allowing the fish market to operate with fewer obstructions. The nearby piers still handled bulk shipments, while the Port of New York “handled nearly as much cargo as all the other Atlantic and Gulf Coast ports combined.” That activity supported almost 25 percent of New York’s economy in 1967. But as skyscrapers walled off Manhattan, as travelers used international airports, and as container ships docked at out-of-sight terminals, New Yorkers forgot that their city was one of the world’s great ports.2

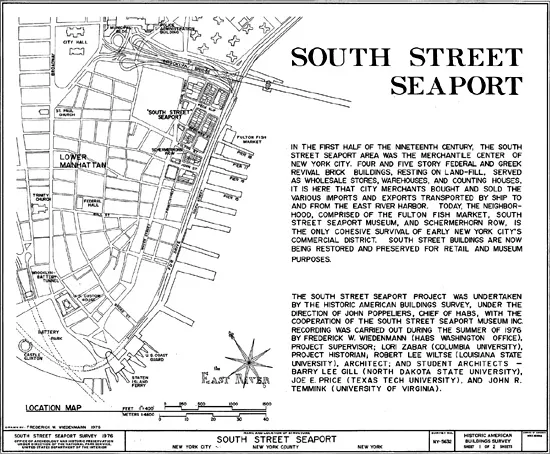

Fig. 1.1. Lower Manhattan map, 1976. (HABS NY-5632; drawing, Frederick W. Wiedenmann; American Memory Project, Library of Congress)

The growth of Gotham itself threatened the port’s viability. As early as 1929, the tristate Regional Plan Association proposed moving maritime operations to New Jersey. A dearth of investment, too little space in Manhattan, and a clash between intransigent shipping executives and corrupt longshoremen posed severe problems, ones that were magnified by Hollywood. On the Waterfront (1954), which won eight Oscars, portrayed the port as dangerous and sinister. Yet that same year, National Geographic celebrated the world’s busiest harbor with its one thousand vessels departing each month. More significant for the city’s four hundred finger piers was the waning of break-bulk cargos and waxing of containerization, a trend that was pushed by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. After the City of New York refused to relinquish control over its finger piers, the Port Authority built the world’s first container port at Elizabeth, New Jersey. While 18 percent of the port’s general cargo was containerized in 1968, it leaped to 70 percent by 1977, with three-quarters of the containers offloaded in New Jersey. Transatlantic travel also changed. Beginning in 1958, most travelers chose air over sea, and the wharves slowly became ruinous.3

Remnants of Manhattan’s nautical history were still evident downtown. The Cunard Building (1921) included superb oceanic murals, and the Beaux-Arts Custom House (1907) featured twelve statues representing history’s great seafaring powers. A proposal to convert the Custom House into a marine museum aired in 1957. The Seamen’s Church Institute, which itinerant Jack Tars called “the doghouse,” hosted a museum of ship models and paintings, but its curator admitted to a chagrined Karl Kortum that he “personally detest[ed] all sailing ships other than yachts” and thought that a floating ship museum such as Kortum’s Balclutha “couldn’t be made a go” in Gotham. He warned that “very few of the visiting public are ‘ship minded.’” The institute eventually lost interest and sold much of its collection in 1968. Perhaps the most dazzling space was India House (1853), a private club founded in 1914 by Wall Street mogul James A. Farrell Sr., president of US Steel Corporation. He developed what James Morris called a “shrine of nautophilia, as polished and spanking as a ship itself.”4

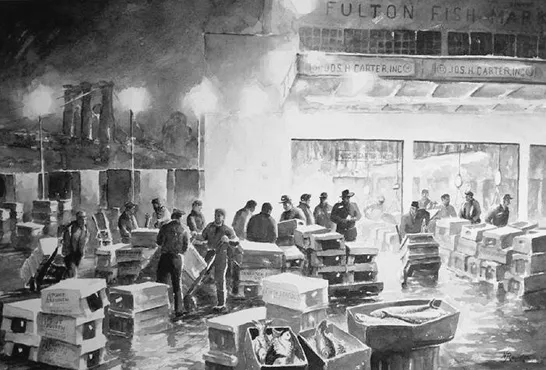

Fig. 1.2. Carter Fish Company, 4 a.m., Fulton Fish Market, 1993; watercolor painting by Naima Rauam.

The most authentic maritime operation was the world’s largest open-air fish market half a mile away. In addition to first-floor shops in Schermerhorn Row and on nearby streets, the Fulton Fish Market (FFM) district centered around South Street’s Tin Building (1907) and New Market Building (1939). The FFM attracted uptown curiosity seekers who, afflicted with the bourgeois blues, had come, since the 1880s, to observe the “incautious, unguarded, unfettered life of the working classes.” Their “brawling, foul-mouthed, hard-working, fish-slinging, fun-loving” ways, said Peter Stanford, “kept it alive.” Born on South Street, New York Governor Alfred E. Smith worked there as a basketboy. Later, the governor and presidential candidate paid tribute and boasted of his FFM degree. Gradually its iconic Gloucester fishing schooners were being displaced by newer methods of transportation, distribution, and sale. By 1958, only 6–7 percent of the catch arrived by sea. As Stanford recalled, four or five ships still tied up there in the early 1960s, but they were not “the graceful, elliptical-sterned schooners” of his childhood. What remained of the FFM was its archaic culture, including vendors whose discarded scraps the poor retrieved for fish soup.5

“Cities Need Old Buildings So Badly”:

The Clash between Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs

Meanwhile, three giants by the names of Moses, Jacobs, and Rockefeller were shaking Manhattan to its bedrock. Over the previous decades, Robert Moses left a massive footprint in public works, but there was, noted Ada Louise Huxtable, “the ‘good’ Moses versus the ‘bad’ Moses.” The latter ravaged the old port. To funnel traffic into Wall Street, he built the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel (1950), which undercut the city’s pedestrian ferries. Clearing out Sailortown, which ran inland from the East River’s shipyards, he also built the Alfred E. Smith Houses (1953), a dozen high-rises wedged between Chinatown and the FFM. They became what the museum called a “massive belt of waterfront public housing.” He also hawked construction of a river-to-river Lower Manhattan Expressway, which the city prematurely placed on its map in 1960. Then came Jane Jacobs. With a blend of humanism, urbanism, and libertarianism, she, more than anyone else, made Americans think differently about cities. The duel between Jacobs and Moses defined Gotham’s development. Since Moses’s proposed ten-lane, elevated expressway would destroy neighborhoods from Chinatown to SoHo, including Jacobs’s West Village, she thundered, it would “LosAngelize New York!” Her masterpiece, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), became, said the Atlantic, “the most influential American book ever written about cities.” She even suggested retaining “plain, ordinary, low-value old buildings.” Yet urbanists such as Lewis Mumford scoffed at her notion that “cities need old buildings” for their vigorous growth.6

David Rockefeller hoped to prove Jacobs wrong. While his family was becoming “the leading promoters of urban renewal in America,” and even maneuvered Moses out of office in 1968, his Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association (D-LMA, 1958) issued plans to remake the area south of the Brooklyn Bridge. At the time, Lower Manhattan had a working population of four hundred thousand but only four thousand residents. With such words as “erosion, decay and exodus,” the D-LMA called it a wasteland. It proposed leveling the land between Old Slip and the bridge; eliminating cramped and crooked lanes; widening Fulton, Water, and South Streets; building a loop to connect to the proposed expressway; moving the FFM to the Bronx; and constructing residential high-rises for Wall Street employees. Welcoming the project, a Times editorial predicted “a great future” for downtown. Yet Times columnist Meyer Berger reminded readers that “almost all of the properties … were handsome dwellings a little over 100 years ago.” All told, those 564 acres downtown included 2,776 buildings, of which 52 percent were at least a century old, while 17 percent had been built between 1858 and 1883. With the possible exception of Federal Hall, Fraunces Tavern, and City Hall, old Lower Manhattan was doomed.7

Fig. 1.3. Proposed World Trade Center on the East River (center), with World Trade Mart (far right) and hotel (left), D-LMA, January 1960. (Courtesy of Rockefeller Archive Center)

In 1960, City Hall and the D-LMA amplified a proposal for a tract from Old Slip to Fulton Street (and South Street inward to Pearl and Water Streets) to include not only a seventy-story hotel, an exhibition hall, and a new stock exchange but a five-million-square-foot World Trade Center for a workforce of up to forty thousand. Paired with a proposed World Trade Mart on the FFM site, the WTC would be 20 percent larger than Chicago’s Merchandise Mart, the world’s biggest building. The D-LMA approached the Port Authority, which, as a quasi-independent agency, could bypass local regulations. The city pushed through zoning changes in 1961 to pave the way for high-rise construction. Skyscrapers would be set “back in plazas, inside property lines, and at a greater average height and bulk,” thus altering streetscapes that had defined cities for over a millennium.8

Though historian Samuel Zipp has suggested that urban renewal “was undone by the experiences and critiques of those living in the places it left in its wake,” the question was, who even lived there? Much of it was, alleged the Times, “a ghost town” with few residents. You “could count the population on your hand,” said planner Richard Weinstein. Yet some of the invisible inhabitants were squatters or poor folk; others were bohemians and artists chased out of Greenwich Village by high rents. Artists Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Mark di Suvero, for example, lived there but laid low because of building-code violations or their unconventional lifestyle. Johns mined the garbage of its “narrow and filthy streets” for his mixed media. The “decrepit structures” were “good for nothing at all,” said the Times, as their $20-per-foot tax valuations paled compared to those at “$700 a foot in skyscraper country.” If the plan was approved, the area would become “a city of vistas, of promenades, and greenery along the waterfront.”9

Opposition soon arose. Businessman Edmund (Ted) A. Stanley Jr. was president of Bowne & Company Stationers (1775), a family-owned firm that employed 150 in a soon-to-be-demolished, Front Street building. When he started working downtown in 1949, his “father set his watch at noon by the ball dropping on the Titanic Memorial atop the Seamen’s Church Institute.” Photographing buildings before they fell to the wreckers, he led a businessmen’s group opposing the D-LMA. Many in the arts and business communities criticized the D-LMA plan to demolish Wall Street’s impressive New York Stock Exchange (1903). Jacobs called the entire plan “an exercise in cures irrelevant to the disease.” If Rockefeller wanted to correct downtown’s imbalance between peak and off-hours populations, she suggested that the only reasonable solution would be to draw outsiders to the area. In late 1961, the governor of New Jersey forced a change of venue. Because the Port Authority required his assent, the proposed WTC was moved one mile west to a site whose Hudson Tubes served New Jersey. The three hundred businesses along the West Side’s Radio Row were no match, moreover, for the Rockefeller juggernaut.10

Thinking that a maritime museum could draw outsiders, the D-LMA’s executive director, L. Porter Moore, approached Moses in the late 1950s about converting the ferry terminal building at the foot of South Street to a museum. Moore wanted to move the galleries of the Marine Room at the old-fashioned Museum of the City of New York, at Fifth Avenue and 103rd Street, and create an exhibit using its paintings, models, and evocative diorama of the mid-nineteenth-century “street of ships” along South Street. Moses warned that private monies would be required because the city’s budget was strained. More ambitiously, Jacobs proposed a “great marine museum” like Kortum’s in San Francisco, with “the best collection [of ships] to be seen and boarded everywhere.”11

Of all critics, Ada Louise Huxtable best articulated the changing scope of preservation. She had worked as a freelancer critiquing preservation, architecture, art, and technology, but Penn Station’s demise was a turning point for her, the movement, and for the New York Times, which hired her as its first full-time architecture critic. “It’s time we stopped talking about our affluent society,” she wrote in an editorial denouncing Penn Station’s destruction. “It is a poor society indeed that … has no money for anything except expressways to rush people out of our dull and deteriorating cities.” Though Mumford had written brilliant essays for the New Yorker, Huxtable turned “consistently bold and forthright” criticism into a public art that crossed disciplines and quickly gained fame. She angered many people but noted that there were “no constraints, ever, on anything” she wrote, “inside or outside of the Times.”12

With Huxtable’s interests in preserving vernacular buildings, conserving streetscapes, and emphasizing their authenticity and humanity, she shifted the movement. As with New York’s Municipal Art Society (1893) and the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society (1895), preservationists had mostly supported the connoisseur and patriotic traditions by restoring architectural masterpieces or the homes of patriotic leaders. New Englanders had preserved everyday structures, but they privileged certain traditions and, except in rare cases such as Boston’s Beacon Hill, did not save their streetscapes. Challenging the National Trust for Historic Preservation (1949) and Colonial Williamsburg (1926), Huxtable also embraced the then-derided architectural eclecticism and technology of the nineteenth century. Mainstream architects and planners resisted her thinking, as they were “often openly hostile to historic buildings and districts.” As a result, John Young, a student in Columbia University’s graduate preservation program in 1968, realized that his quest for authentic streetscapes was “a marginal even subversive activity.”13

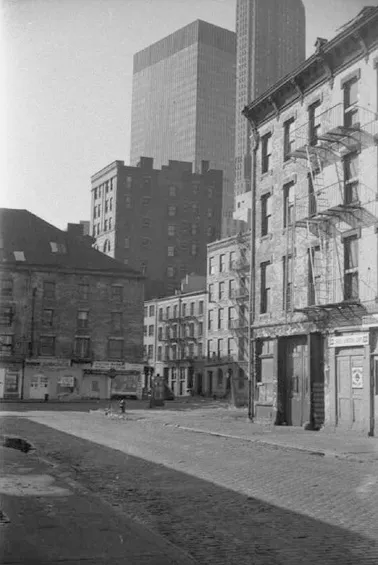

Fig. 1.4. Front Street, looking southwest at Blocks 96W (right), 74W (center), and 74E (left), with Chase Manhattan Bank towering over the ten-story Green Coffee Exchange, 1968. (Photo, John Young and Urban Deadline)

Remarkably, Huxtable cut her preservationist teeth in Lower Manhattan, where planners, bureaucrats, and developers were obliterating the landscape from the Brooklyn Bridge to the Battery. After reading the D-LMA’s plans in 1960, she mocked the planners’ “occupational insanity” and their “uncontrollable urge for … the crashing roar of bulldozers clearing away the past.” That led to her 1961 feature story, “To Keep the Best of New York,” in the Times’s Sunday magazine. Walking the seaport, one of the city’s few areas with an intact early nineteenth-century flavor, she saw “eloquent reminders of sailing and shipbuilding, of schooners and spices, of a fascinating, vital chapter of New York’s early commercial life.” Alluding to John F. Kennedy’s endorsement of preservation, she called for judiciously mixing the old and new.14

After chiding the modernism-addicted American Institute of Architects that “the art of architecture has died,” Huxtable again toured what was called the Brooklyn Bridge urban renewal districts. To the north of Pearl Street, the “‘total clearance’ philosophy” ...