![]()

1

Genetics

In his book Without Conscience (1999), Dr. Robert Hare describes a set of female twins who differ like “night and day,” “heaven and hell.” One twin grows up to be a lawyer with ambitious career prospects, while the other develops drug addiction, has numerous encounters with the law, and demonstrates many of the traits of psychopathy. Despite years of intensive self-scrutiny, the twins’ supportive and attentive mother cannot identify a mistake, event, or way in which the girls might have been treated differently that could have resulted in the troublesome behavior of one of the twins. Despite sharing the same womb and being raised in the same nurturing family environment, the twins are drastically different. Yet one notable factor is that the sisters are not identical twins—they are fraternal.

Children have the physical, cognitive, and emotional means of being physically aggressive toward others by 12 months of age, and individual differences in the frequency and severity of this aggression can be observed shortly thereafter (Tremblay 2008). To what extent are these individual differences due to genes versus the environment of the child? The idea that antisocial or criminal behavior is heritable is one that has been very controversial over the years, but it has gained substantial scientific evidence to support it (Raine 2008, Moffitt 2005). Recently, studies have also begun to specifically examine the genetics of psychopathic personality traits. This chapter outlines evidence from two overarching fields of genetic research: behavioral genetics and molecular genetics. Behavioral genetics studies aim to disentangle how much a disorder is the result of genes versus environmental factors; this approach includes twin and adoption studies. The next step is to identify specific genes that may confer risk for the disorder, which is the task of molecular genetics. The main findings from these studies are that psychopathic traits appear to be moderately to highly heritable and share some common genetic factors with antisocial behavior more generally, but they also are attributable to unique genetic factors. Studies examining specific genes that may confer risk for psychopathic traits are just beginning, but have provided some clues as to the biological pathways that may underlie psychopathy.

As discussed in the introduction, genes represent the first source of biological variation between individuals; they facilitate the development of the structure and organization of the brain, and continue to have an influence throughout the life span through their effects on neurotransmitter and hormone systems, which facilitate brain functioning. The functioning of a particular gene may depend on the presence of other genes, as well as environmental factors, which have the capability of altering the way that genes are expressed (e.g., they may be able to turn genes “on” or “off”). Therefore, the association between a single gene and a behavior or trait is typically very small. This is also due to the fact that the pathway from the activity of a single gene to behavior is complex, and countless additional factors are introduced at each step, introducing additional variance. Thus, large sample sizes are often required in studies attempting to link a single gene to a particular disorder. Identifying the genes that are associated with psychopathy has the potential to further our understanding of the causal chain of events that lead to its development.

Behavioral Genetics

In studying the genetics of psychopathy, the first step is to establish whether psychopathic traits are heritable and the extent of the potential heritability. Behavioral genetics studies have begun to answer these questions and others. Before outlining evidence from these studies, the methodologies used in the field of behavioral genetics are first briefly outlined.

Behavioral Genetics Methodology

Behavioral genetics studies usually involve twin or adoption studies. Since there are currently no adoption studies of psychopathy, we focus on the twin methodology. Twin studies typically compare samples of monozygotic (MZ) or “identical” twins, who share 100 percent of their genes, to dizygotic (DZ) “fraternal” twins, who share approximately 50 percent of their genes. It should be noted that when we say 50 percent, we are actually referring to only the genes that can vary across individuals; all humans share about 99 percent of their genes, but the remaining 1 percent varies, and it is this portion that is of interest in genetics studies. Furthermore, DZ twins share 50 percent of their variable genes on average, but this can vary considerably, with some DZ twins being more similar and others less similar.

In behavioral genetics studies, the similarity of MZ twins on a given trait is compared to the similarity of DZ twins on that trait. If MZ twins are more similar than DZ twins, then it can be inferred that the trait being measured is at least partly due to genetic factors. Across large samples, statistical modeling techniques can determine the proportion of the variance in a particular trait or phenotype (in this case, psychopathy or a subcomponent of it) that is accounted for by genetic versus environmental factors.

Genetic factors either can be additive or nonadditive. Additive means that genes summate to contribute to a phenotype. For example, hypothetically, alleles at five different locations may contribute to the determination of an individual’s height (the phenotype). An additive effect means that the individual’s height is the sum of the effect of each of these alleles on height. Additive effects are passed on in families. The more alleles you have that are similar to your parent or sibling (e.g., alleles coding for height), the more similar you are on a given trait (e.g., height). If a genetic effect is additive, then the correlation between DZ twins will usually be about half of the correlation of MZ twins (because they share half the number of genes).

Nonadditive effects mean that genes are configured in a unique way to form the personality trait, rather than simply being the cumulative effect of several genes. This means that if just one gene is different, the personality trait may not exist. Nonadditive effects come in three types—dominance, epistasis, and emergensis. Dominance means that if one of two alleles is dominant, the phenotype will reflect the dominant allele, rather than a summation of the two alleles. For example, alleles for brown eyes tend to be dominant, whereas alleles for blue eyes are recessive. If an individual has one allele for brown eyes and one allele for blue eyes, the result is that the individual will have brown eyes, rather than a mix between brown and blue. In the case of dominance, DZ twin correlations are expected to be about 25 percent of the MZ correlations. Epistatic and emergenic effects simply mean that multiple genes must interact or be configured in a specific way in order for the phenotype to be present. Because these configurations are so specific, these types of effects do not run in families and can be thought of as random; thus, the correlation between DZ twins is typically close to zero, whereas the effect will be present in MZ twins who share the exact same genes.

Environmental effects can also be divided into two types—shared and nonshared. Shared environmental effects are those that are common to both twins such as socioeconomic status and parental discipline. Non-shared environmental effects are those that are unique to each twin; the most common example of a nonshared environment is a peer group.

Aside from addressing the extent of heritability of psychopathic traits, behavioral genetics studies can help to answer a number of additional questions about psychopathy. For example, are psychopathic traits more heritable than criminal behavior in general? Also, how much genetic variation is shared across the different features of psychopathy (i.e., do the interpersonal, affective, and antisocial traits stem from common genetic factors?), suggesting that this is in fact a unified disorder? Or are these independently derived maladaptive personality traits that combine in some individuals to form what we think of as psychopathy? Answers to these questions may provide useful information regarding the conceptualization of psychopathy.

Evidence from Behavioral Genetics Studies

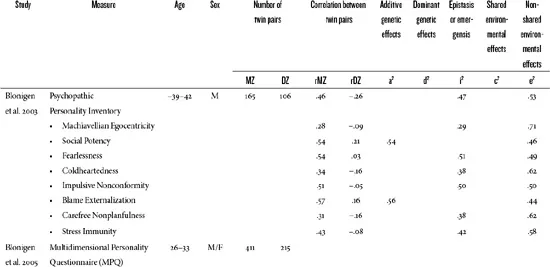

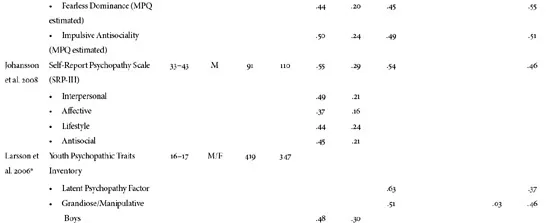

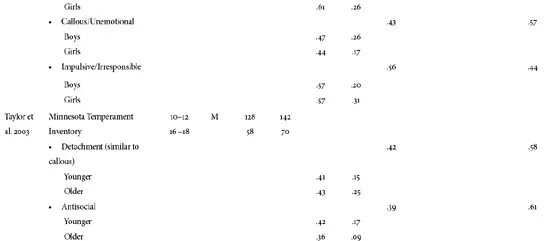

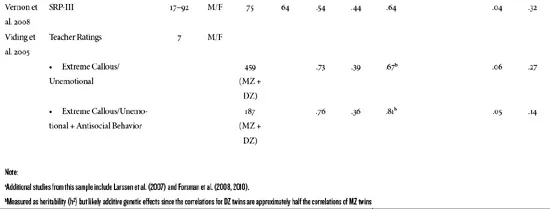

Although several studies have claimed to study the genetics of psychopathy, most of these studies have focused on the antisocial deviance features of psychopathy and not the core personality traits (Blonigen et al. 2003). However, in the past several years, several studies have assessed the genetics of psychopathic traits specifically (see Table 1.1). These studies include participants from as young as age 7 to as old as age 92. These studies have used a variety of measures for assessing psychopathy (or callous-unemotional traits in youth), but all have relied on either self-report or teacher-report ratings. Despite the variance in methodology, four key findings have emerged from these studies.

1. Psychopathic traits are moderately to highly heritable.

The general consensus from these studies suggests that genetic factors account for approximately 40 to 60 percent of the variance in psychopathic traits, an estimate that is consistent with the results of behavioral genetics studies that have examined the heritability of other personality dimensions (Bouchard and Loehlin 2001). This means that, on average, genetic and environmental factors contribute approximately equally to the disorder. It will be important to keep this estimate in mind in the following chapters as we discuss differences in brain functioning and hormone levels—it is important to remember that these biological differences result from both genetic and environmental factors. It is also important to keep in mind that this figure represents an average across a large number of people, and that in some individuals, genes may have a stronger influence on the development of psychopathic traits than the environment, and in other individuals, the opposite may be true.

The majority of behavioral genetics studies of psychopathy report that genetic effects are additive. This means that the genes summate to contribute to the disorder; the more risk genes an individual has, the more likely he or she will be to develop psychopathic traits (for an exception, see Blonigen et al. 2003). We can tell that the genetic effects are additive because studies show that the correlation for DZ twins, who share about half of their genes, is approximately half of the correlation for MZ twins. Genetic factors have also been found to contribute to the stability of psychopathic traits over time. Several studies have established that psychopathic personality is stable (Loney et al. 2007, Lynam et al. 2007). A study by Forsman et al. (2008) found that genetic factors contribute to this stability. In contrast, changes in psychopathic traits over time were found to result primarily from environmental factors, meaning that any changes in the level of psychopathic traits over time appear to be due to environmental influences.

Table 1.1. Behavioral Genetics Studies of Psychopathy

2. Nonshared rather than shared environment accounts for the rest of the variance.

This is a key finding that distinguishes behavioral genetics studies of psychopathy from those of antisocial behavior more generally. Studies of antisocial behavior have most often found that the environment that is shared between twins has an effect on antisocial behavior (Rhee and Waldman 2002, Larsson et al. 2007). However, across all the studies reviewed here on psychopathic personality traits, the influence of shared environmental factors was negligible. This means that although environmental factors are important in the development of psychopathic traits, it is not the environment that is shared between the twins, such as socioeconomic status, school, or neighborhood, that is important. It is the environmental factors that are unique to each twin that are involved. Some researchers hypothesize that peer relationships may account for some of the nonshared environmental influences on psychopathy (Larsson, Andershed, and Lichtenste in 2006), as peer relationships are thought to substantially contribute to differentiation between siblings during adolescence (Pike and Plomin 1997).

This finding represents a divergence in etiology between psychopathic traits and general antisocial behavior. It has been suggested that this finding may reflect the distinction between core personality traits (i.e., psychopathic traits) and “characteristic adaptations,” which are behaviors that result from a combination of core personality traits and environmental influences (i.e., antisocial behavior could be viewed as a characteristic adaptation) (Larsson et al. 2007). The finding of the influence of the nonshared environment but not the shared environment is more consistent with other studies of personality dimensions, which find that almost none of the environmental variance in personality is due to sharing a common environment (Bouchard and Loehlin 2001).

3. Different facets of psychopathy have both common and unique genetic factors.

The idea that the different features of psychopathy are unified and stem from common factors has long been hypothesized (Hare 1970), but has been difficult to confirm. Behavioral genetics studies have a unique ability to provide information about whether the different features of psychopathy actually represent a unified disorder. The finding that there are common genetic factors influencing the distinct aspects of psychopathy would suggest that it is indeed a unified construct. Thus far, two studies have found that some of the same genetic factors contribute to the different facets of psychopathy (Taylor et al. 2003, Lars-son, Andershed, and Lichtenste in 2006). Both of these studies found sizable genetic correlations between the different factors of psychopathy, including callous-unemotional features and impulsive-antisocial features. These studies suggest that there is a strong relationship among the genetic factors that are associated with the different aspects of psychopathy. Furthermore, Larsson, Andershed, and Lichtenste in (2006) found that the different facets of psychopathy covary with a latent overall psychopathy factor, which is also substantially influenced by genetic factors.

One exception to these findings is the study by Blonigen at al. (2005), which found no genetic correlation between the Fearless Dominance and Impulsive Antisocial factors of psychopathy, suggesting that the two factors may derive from independent etiological processes. Although this finding stands in contrast to the strong genetic correlation between psychopathy factors observed by Taylor et al. (2003) and Larsson, Andershed, and Lichtenste in (2006), both of the latter studies also found that there are some unique genetic effects that are important for the different psychopathy factors (i.e., there are unique genetic effects that influence the different psychopathy factors over and above the genetic influence from the latent psychopathy factor). This suggests that despite the fact that the factors of psychopathy tend to co-occur, there may be some etiological factors that differentiate them. Additional studies will be necessary to clarify the degree of shared versus unique genetic contributions to the psychopathy factors, but overall research suggests that there are both common and unique genetic factors underlying the different aspects of psychopathy.

A final interesting point to note regarding the heritability of the psychopathy factors is that each of these studies has shown that the degree of heritability of the different factors of psychopathy (e.g., emotional, interpersonal, lifestyle) tends to be approximately the same, meaning that there are not features of psychopathy that are more heritable than others (Blonigen et al. 2005, Larsson, Andershed, and Lichtenstein 2006, Taylor et al. 2003).

4. Psychopathy shares common genetic factors with antisocial/externalizing behavior.

The genetic correlations between psychopathy factors in the studies discussed above refer only to the “personality” features of psychopathy, and do not include assessments of criminal behavior that are measured on the PCL-R (i.e., items included in the “antisocial” subfactors from these studies reflect traits such as deceitfulness or irresponsibility rather than crime). However, Blonigen et al. (2005) assessed whether the psychopathic personality features shared common genetic factors with externalizing behavior and found that there was significant genetic overlap between externalizing behavior and both the Impulsive Antisociality factor and the Fearless Dominance factor of psychopathy (the latter only in males). Furthermore, Larsson et al. (2007) measured psychopathic personality and deviant behavior in adolescent twins and found that a common genetic factor substantially contributed to psychopathic personality traits and to deviant behavior. Finally, Viding et al. (2005) showed that extreme antisocial behavior was m...