![]()

1

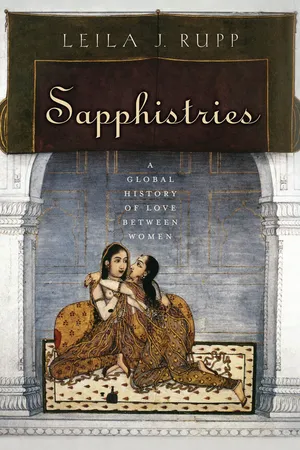

Introduction

Sap•phis•tries \’saf-

\

n: Histories and stories of female same-sex desire, love, and sexuality, after Sappho, sixth century BCE poet of Lesbos.

THE LESBIAN POET Sappho, whatever her erotic history, bequeathed both her name and her place of residence to the phenomenon of desire, love, and sex between women. Her iconic image as a lover of women has transcended the boundaries of history and geography, bestowing on women who desire women the labels Sapphic and lesbian. Because the term Sapphic has a longer and more widespread history than lesbian, I have named this book Sapphistries, an invented word, although not an entirely original one, to embrace all the diverse manifestations of women and “social males” with women’s bodies who desired, loved, made love to, formed relationships with, and married other women.1 Sapphism is a name that stuck through the centuries, and not only in the European tradition. An eleventh-century poet in Muslim Spain earned the moniker “the Arab Sappho.”2 A Japanese loan word, saffuo, coined in the 1900s, refers to female same-sex sexuality.3 A Chinese critic in 1925 translated one of Sappho’s fragments into Chinese, pointing out that women’s same-sex love is called “sapphism.”4 A conference in Melbourne, Australia, in 1995, organized by lesbians from minority ethnic and racial backgrounds, took the title “Sappho Was a Wog Grrrl.”5 How impossible it is to disassociate Sappho from her legacy is suggested by the fact that, in 2008, a Greek court dismissed the request of three residents of Lesbos for a ban on the use of the word lesbian for anyone other than inhabitants of the Aegean isle.6

The only term that has a broader historical reach, if not the same poetics, is

tribadism, from the Greek and Latin words meaning “to rub,” in its numerous linguistic variations. The Arabic terms

sahq, sihâq, and

musâhaqa are all derived from the verbal root

s-h-q, meaning “to pound,

bruise, efface, or render something soft,” sometimes translated as “rubbing.”

7 In Hebrew, the term for women who have sex with other women is

, meaning “to rub.”

8 Female same-sex behavior in Chinese is called

mojingzi, “rubbing mirrors” or “mirror-grinding.”

9 The word in Swahili for a lesbian is

msagaji, which means “a grinder.”

10 In Urdu and related languages, the terms for female same-sex sexual activity—

Chapat, Chapti, and

chapatbazi—are all related to flatness or flattening.

11 Tortilleras is the term used to refer to lesbians in Cuba and elsewhere in Latin America.

12 A French dictionary from 1690 defined a

tribade as “a shameless woman enamored of one of her own sex” and finished off the definition with the simple statement “Sappho was a tribade.”

13 An English pamphlet from 1734 blamed Sappho for introducing “a new Sort of Sin, call’d the

Flats.”

14 So I suppose my title might have more global reach if it were called “Tribadie” or “Rubbing through Time,” but both lack, in my opinion, the elegance of “Sapphistries.” In the interest of elegance, too, my subtitle (and sometimes text) intends “love” to cover desire and sex as well, and “women” to include those with female bodies who might not have identified as women.

It is, I must admit, an audacious undertaking to tackle desire, love, and sexuality across such vast expanses of time and space. On the one hand, the enormous variety of ways that women have come together in societies ranging from ancient China, India, and the Mediterranean world to contemporary Thailand, Mexico, and South Africa can only support the social constructionist perspective on sexuality that insists on the impact of societal structures and concepts in shaping the ways that people experience desire, have sex, form relationships, and think about themselves. On the other hand, the very act of putting between two covers such a wide range of ways that women have loved one another raises the danger that we think of them all in one large category.

Some scholars, for political reasons, insist on that category being called lesbian, even if that was not a term or concept embraced by a particular society.15 Adrienne Rich in 1981 famously introduced the concepts of lesbian existence and the lesbian continuum to embrace a wide range of woman-bonding behaviors characterized primarily by resistance to male domination.16 Since then, debates have raged on about what qualifies a woman as a lesbian throughout history and across cultures.17 Taking off from Rich and following her emphasis on autonomy from male control, medieval historian Judith Bennett argues for the term lesbian-like, which she uses to describe a range of medieval European women. She tells, for example, of two different convents that housed women who fit her concept. One was founded by a widow in Ferrara who put together her dowry with contributions from other women to buy property and establish a community that she managed to keep out from under male Church authority for almost twenty years. She and her companions lived together, devoting themselves to religion and good works, and when she died, she named another woman her heir, with the obligation to maintain the community in the same form. With the language of piety, she created a life independent of the control of men, whether husbands or Church authorities. The other convent was in Monpellier and housed former prostitutes who were old, repentant, or moving away from prostitution to marriage. They were not cloistered and had only minor religious duties. In neither case is there any evidence of same-sex desire or sexual behavior, but that is precisely Bennett’s point: that, in the first case, the desire for independence from men is “lesbian-like” and that, in the second, the long historical connection between prostitution and same-sex love is suggestive.18

I understand the appeal both of boldly claiming visibility where it barely exists by embracing the term lesbian and of keeping the association while recognizing the differences between contemporary lesbians and what Bennett would call “lesbian-like” women of the past. But I have chosen a different path. Too broad use of the term lesbian, I think, downplays the differences among women, especially when the concept and identity of lesbian is available and women choose not to embrace it, as occurs in many parts of the world today where a transnationally available lesbian identity is known but women who desire women have different ways to think about themselves. So I choose to use a term that does not apply to women themselves but to their histories and stories. And, unlike Bennett, I am not willing to consider women who sought independence from men and women who sought the privileges of men, if they did not also give some hint of desire or love for women, as part of sapphistries.

The question of whether sex matters in determining who is part of “lesbian” or “lesbian-like” history has been much debated. This issue came to the fore particularly in the context of romantic friendships, the passionate and socially acceptable ties between women in the nineteenth century that first came to attention in Carroll Smith-Rosenberg’s classic article “The Female World of Love and Ritual.”19 Then Lillian Faderman, in her pioneering book Surpassing the Love of Men, connected romantic friendship to contemporary lesbian feminism while arguing that most romantic friends “probably did not have sexual relationships.”20 Whether or not romantic friends—or other women who expressed passionate love for each other—engaged in sexual acts is a question that increasingly aroused fierce debate in the context of the feminist “sex wars,” a struggle born in the 1980s over emphasizing the pleasure as opposed to the danger of sexuality. The most recent studies of romantic friendship, by Martha Vicinus and Sharon Marcus, leave no doubt about the erotic and sexual aspects of at least some of these relationships.21 In the ongoing debate about how much sex matters, I come down firmly on the side of the centrality of sexual desire, erotic love, and/or sexual behavior in thinking about which women in the past and present are part of this story.

But of course the difficult question is, what counts as desire, love, and sex? Are expressions that sound to our modern ears like desire actually that? Can we tell erotic love from nonerotic friendship? Is genital activity necessary to a sexual act? Is genital activity always a sexual act? These latter questions are especially difficult. Having read about the caressing of breasts between two African American women in the mid-nineteenth century and European and U.S. romantic friends kissing and hugging and lying with heads in laps, my students in one class, having been asked what counts as sex, thought they knew where to draw the line: what they called “tongue action” in kissing and “below the waist action” in caressing counts as sex; anything else does not. But such a definition, though clearly making sense to twenty-first-century U.S. college students, cannot stand up to the girls and women in Lesotho who French kiss, rub one another’s labias to stretch and beautify them, and even engage in cunnilingus but who insist that it is not sexual because there is no penis. Nor can it stand up to !Kung San girls, who likewise engage in sexual play but are not sure what it means, asking, “Can two vaginas screw?”22 So what looks very much like sexual activity to us may not be understood that way, and what may not seem to cross whatever line we imagine divides foreplay from sex may in fact very much count as sex to the women involved. And all the same uncertainty applies to what counts as desire and what counts as erotic love.

Then there is the problem of evidence. Given the long history at play here and the extremely limited literacy of women, testimony from the mouths or pens of women is very rare until modern times. So most of the evidence we have through the centuries comes from men: their prohibitions, their reports, their literature, their art, their imaginings, their pornography, their court cases. Here and there the views of women themselves can be gleaned, and I have tried mightily to make use of the creative research of scholars who have listened and heard the voices of women, even if we need to acknowledge that the context and filtering of such voices mean that they are in reality representations rather than some fundamental truth about experience. We also have to assume that the representations, both textual and visual, created by men tell us something about the possibilities of love and sex between women in different societies.

But I recognize that any decision about where to draw the lines—who is in and who is out in a history of love between women—is tricky. Perhaps most problematic is my inclusion of female-bodied individuals who did not or do not consider themselves women, even if they did not or do not consider themselves men. Judith Halberstam develops the concept of “perverse presentism” to suggest that “what we do not know for sure today about the relationship between masculinity and lesbianism, we cannot know for sure about historical relations between same-sex desire and female masculinities.”23 Because we often do not know what such individuals themselves thought about their gender and sexuality, and because the act of female bodies having sex together was often what the authorities saw as most important, I include them here, being careful not to assume either that they were transgendered in a contemporary sense or that they were like female-gendered women who desired or had sex with other female-gendered women.

Although most of my sources are conventional historical ones, I am also taking liberties by using some literary texts not as historical sources but as ways to help us imagine answers to questions that cannot be addressed with existing evidence. These are texts that reflect their own time and place while portraying another. So, for example, I use Erica Jong’s Sappho’s Leap: A Novel, which reflects contemporary thinking about the fluidity of sexual identities, to engage with the historical Sappho’s sexuality; a short story by Sara Maitland, “The Burning Times,” to think about the possibilities of witchcraft accusations and love between women; and, in the riskiest historical move of all, Jackie Kay’s Trumpet, a novel about a contemporary British biracial transgendered musician, to imagine what the wives of women who secretly crossed the gender line through past centuries might have thought. I am aware of the conceptual risks posed by such a strategy, but I believe that the advantages outweigh the danger of contributing to a vision of transhistorical sameness.24 And I am inspired by Monique Wittig, who wrote in Les Guérillères, “Make an effort to remember. Or failing that, invent.”25 These literary texts, as imaginative interpretations, remind us that historical scholarship, too, although based on evidence, is also an act of interpretation.

Sapphistries not only brings together extremely scattered and disconnected research on a wide range of phenomena but also, I hope, contributes to ongoing discussions about the nature of sexuality across time and place. Certainly the range of ways that women have come together makes clear that how women act on their desires, what kinds of acts they engage in and with whom, what kinds of meanings they attribute to those desires and acts, how they think about the relationship between love and sexuality, whether they think of sexuality as having meaning for identities, whether they form communities with people with like desires—all of these are shaped by the societies in which they live.

At the same time, however, we must confront the persistence of certain patterns in the history of female same-sex sexuality, particularly the role of female masculinity and the eroticization of friendship. That is, we find very different societies shaping erotic relationships between women in quite similar ways. Here it is useful to remember that anthropolo...