![]()

1

The Inevitable Fatality of the Couple

O happy dagger.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Romeo and Juliet

their heart grew cold

they let their wings down

SAPPHO, fragment 42, Anne Carson’s translation

Killing Me Softly

As I suggested in this book’s introduction, couple love is an ideological apprenticeship in loneliness — a loneliness so upsetting that it’s often displaced onto singles. But if you don’t believe me, pick up a book. Watch a movie. Listen to a song. Or spend any amount of time wondering about the person you love that you can’t live without. And then think about all the lonely hearts out there that seem to have it worse. In this chapter, I’d like to indulge in some lonely words about what it means to be in love, or, more precisely, in a love that is predicated on the supremacy of the couple — a form of love that insists that the whole world should be created, sustained, or connected by a relationship with just one other person. This kind of intensity makes a relationship an impossible thing to sustain, perhaps explaining why so many relationships are destined for failure. At hand is an appeal to ancient forms, with eternal and immortal words that fill our heads with perhaps the most deadly of myths.

Let’s first briefly go to the movies. A classicist educated at Harvard, Erich Segal, wrote a story called Love Story, which became a New York Times best seller and the number one box office attraction of 1971. Barbara Walters, on television, helped launch its best-seller success by claiming that she couldn’t put the book down even though she had been crying all night reading it. And thus the author was a frequent guest of talk shows — not the most likely early career of a then Yale classics professor.1 In the early seventies, my parents’ generation wept throughout the melodramatic film adaptation (directed by Arthur Hiller) of the story of two people, a preppy Harvard “hockey jock” (played by Ryan O’Neal) and a will-die-too-soon Radcliffe music student (played by Ali MacGraw). Its imprint on popular culture, both as a narrative and as a movie with a very recognizable theme song, persists to the present. Never far from an exaggeration, Al Gore, over a decade ago, proclaimed that he and his wife, Tipper, were the models upon which the story was based. His claim was only partially true: Tipper was known to the author but was not a source of inspiration for the Jenny character. Al Gore and Tommy Lee Jones (who had a small role in the film) were amalgamated into the character of Oliver Barrett IV, according to a 1997 New York Times interview with Segal, who had met them both while he was on a 1968 sabbatical at Harvard.2

When I watched this film after having seen the book throughout my childhood, unopened but cherished on my mother’s bookshelf, I felt some odd forms of awful affection for the buildings of Harvard. Much of the movie feels like one big montage honoring that ancient American institution, which seems to radiate so much charm and value that the buildings themselves can stand in for the monumentality of falling in love, even if we’re not quite sure why the film’s characters like each other. But it’s too easy to mock and disagree with the film. It has a contagious and enduring logic that deserves our attention. It teaches you about the couple’s inevitable fatality; it prompts you to want this kind of devastation.

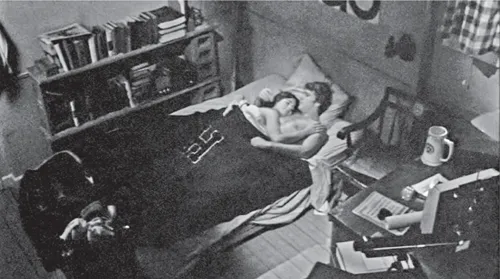

To do as much, Love Story showcases what you need to do in order to enroll in this lonely school of coupledom, and nowhere more clearly than in Jenny’s hospital deathbed scene. Oliver, who has just returned from borrowing money from his father to pay for Jenny’s ineffective medical treatment, is left alone with Jenny to share the couple’s last words. Jenny does something few dying people do in these iconic scenes of morbid sentimentality:3 she asks Oliver to hold her, “really hold” her, by lying “next to her,” thereby requiring him to enter her deathbed. It’s her final request. The way this tender scene is shot is crucial: the frozen posture of the embracing couple is illuminated by an eerily beautiful light — the camera hovering at ceiling height, just to the right of the bed, so we can watch, from above, Oliver holding a supine Jenny, their cheeks touching. This shot visually recalls the first bed scene of their romantic love; by being similarly lit and shot from a similar vantage point, it invokes parallels between the sexbed, where they consummate their love, and the deathbed, which punctuates and defines their love. This view is an exemplary view of the couple.

Love Story: Deathbed. Screen capture from Love Story (dir. Arthur Hiller, 1970).

After Jenny dies, Oliver leaves the bed, the hospital, and the awaiting family members. The ending shots are the same shots that began the film. The opening: there is a pan over Central Park, tilting down and tightening focus onto a lonely Oliver, sitting, turned away from the camera, looking off to the right, refusing to focus on the skating rink where he was recently skating for Jenny’s final moments of amusement (she’s too sick to join him but has always loved watching him on the ice). Oliver has taken the place where Jenny was sitting (although we won’t realize this substitution until the film’s conclusion), so his lonely seat, as he stares out over an empty winter scene (with no Jenny in sight), is a reminder of what he has just lost. Then we hear Oliver in a voice-over, interrogating the point of the love story that’s about to be told: “What can you say about a twenty-five-year-old girl who died? That she was beautiful and brilliant. That she loved Mozart, Bach [we hear a slight, bemused chuckle in Oliver’s voice], the Beatles, and Me.” Sadly, these are the most salient details of this too-short life, and the movie barely deepens a sense of her qualities or her passions. That’s not the point of this love story. It’s not a story of a particular girl. Hiller wanted this story to be a “universal story.” So rather than drench us in deep detail or complex character development, the film relies on camera movement, the Harvard setting, and the musical score to not tell the story of a particular life. The story, instead, is about the loss, which might go by the name “couple.” We are made witnesses to a fatal relational dynamic between two people (dead Jenny and lonely Oliver, the “me” who can be as beguiling as Mozart, Bach, and the Beatles).

Love Story: Sexbed. Screen capture from Love Story (dir. Arthur Hiller, 1970).

According to the sociologist Georg Simmel, “A dyad … depends on each of its two elements alone — in its death, though not in its life: for its life, it needs both, but for its death, only one. This fact is bound to influence the inner attitude of the individual toward the dyad, even though not always consciously nor in the same way. It makes the dyad into a group that feels both endangered and irreplaceable, and thus into the real locus not only of authentic sociological tragedy, but also of sentimentalism and elegiac problems.”4 Simmel does not mean, here, that we always die alone (even though we probably do). He’s making a comment on the anxious form of attachment that marks couples quite differently than other groups (say groups of three or more people). The durability of the couple obviously requires the life of both of its members — the life of the couple is a shared activity by both parts of the dyad. But the death of one of the members brings about not only the death of the member but also the death of the couple — the group of the couple ceases to exist if one of its members dies (unlike any other group composed of three or more people). So deep feelings of morbid and moribund desperation encircle this group formation, and this quality generates a panic that also makes the group (the couple) feel unique — only if this one particular person lives can my relationship, my group, endure.

So the couple becomes a “locus” of “sentimentalism and elegiac problems.” And Love Story is a hyperbolic illustration of such a locus: the love plot begins and ends with death, and we’re forced to be haunted by a sense that despite all the beauty of Oliver and Jenny, in montage, making snow angels in Harvard’s stadium, the angel of death is closely hovering. A quiet, desperate, and upsetting feeling pervades the dyad because it knows that it’s always considering death and dying: one wrong move, one accident, one untimely diagnosis, and the relationship (as well as one of the members of that relationship) will end. And, to be honest, both parts of the couple will eventually cease. So the other’s death will certainly point the way to your own. Dyads, indeed, are always dying.

When Oliver and Jenny marry (as all good couples should), they use some verses from Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Walt Whitman as their wedding vows. While they stand up together, in their modern, nondenominational ceremony, the camera does something it hasn’t done yet in the film: it circles the couple completely, just as Jenny finishes quoting, “A place to stand and love in for a day, / With darkness and the death-hour rounding it.” As the camera rounds it, the couple stands, and it’s positioned as a necessary, circular creature, encircled by death. Certainly many ancient myths, poems, ideas, novels, and films serve as the couple form’s moribund foundation. But since a classicist made up this story, one might think about one of the most famous love stories in antiquity’s canon: Aristophanes’ speech in Plato’s Symposium, in which we are treated to a rounding off of the couple, and a dire account of division, death, halving, and thus not having, which makes couple love a desperate thing to embrace. This speech has its hands all over love, and innumerable examples of a couple’s wholeness, roundness, and eternity owe their emotional clichés to Plato’s caricature of Aristophanes (a contemporary iteration of the myth formally orders the sentimentality of John Cameron Mitchell’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch [2001]). Here’s what Aristophanes contributes to the symposium, a religious story about what it means to fall in love: “First you must learn what Human Nature was in the beginning and what has happened to it since, because long ago, our nature was not what it is now, but very different. There were three kinds of human beings, that’s my first point, not two as there are now, male and female. In addition to these, there was a third, a combination of those two.”5 Much can be and has been said about the queerness of this etiology of sex difference, but rather than fixate on sex difference (or sex sameness), I’m more intrigued by the menacing effect of becoming two (rather than three).6 See, we have in this myth strange human creatures that were made up of four legs and arms, two faces, and one head, and “each human being was completely round” (25). These round things were raucous and crazy, and as a group they were a threat to the gods that needed to be punished: “In strength and power … they were terrible, and they had great ambitions” (26). To curtail their power, their aspirations for immortality, Zeus had to cut the singular, round beings into two and issue an enduring threat: “But if I find they still run riot and do not keep the peace … I will cut them in two again, and they’ll have to make their way on one leg, hopping” (26). Hence, one becoming two is an act of division that is the basis of human control. These three kinds of creatures, which together could pose a threat to the gods, are cut apart and mesmerized by a logic of divisions, a logic of two, a logic that really does divide and conquer.

It wasn’t enough for Zeus to cut them down to halfsize. He’s a bit of a sadist, and he forces them to fixate on that cutting, their coupling: “As he cut each one, he [Zeus] commanded Apollo to turn its face and half its neck towards the wound, so that each person would see that he’d been cut and keep better control” (26). Control means making the one and the many into halves, with wounds, wanting desperately to have:

Now since their natural form had been cut in two, each one longed for its other half, and they would throw their arms about each other, weaving themselves together, wanting to grow together. In that condition, they would not do anything apart from each other. Whenever one of the halves died and one was left, the one that was left still sought another and wove itself together with that. Sometimes the half he met came from a woman, as we’d call her now, sometimes it came from a man; either way, they kept dying. (26-27)

Coupling is a form of constant dying in this scenario, and even Zeus eventually “takes pity” and adjusts their bodies so that they can at least get somewhat closer (usually through the act of sex). But this searching for your lost half never ceases. Human nature is kept in line by this pitiful condition. No matter how you slice it, you’re alone, desperate to find your other (better) half, or, if you’ve found your other half, desperate to stay and grow and die together.

Plato has Aristophanes dress this wound obsession up with a now-so-familiar-it’s-so-cliché sentiment. He imagines Hephaestus offering “all the good fortune that you could desire” (29): “I’d like to weld you together and join you into something that is naturally whole, so the two of you are made into one. Then the two of you would share one life, as long as you live, because you would be one being, and by the same token, when you died, you would be one and not two in Hades, having died a single death” (28). Why this option is “good fortune” eludes me, but it permeates the ancient story of romantic coupledom that is both an original curse of being too strong as one, and life’s great destiny as something awfully divided: to die, reamalgamated, together as one, in Hades. To become well rounded, in fact, to become round again, requires that you first be halved, then prompted to find that ripped-off half, and, once finding it, be forced to enter into a deathbed in order to become whole. An impossible thing, wholeness, especially since Hephaestus doesn’t usually show up to help any of the desperate couples I’ve met on this earth. No one really gets to share a life marked for death so unified.

After the marriage scene in Love Story, the camera never circles, fully, any character or object again in Hiller’s film. The camera movement is still often dramatic but is purposefully used to punctuate the half-ness of any character’s unity. We witness moments when Oliver is shot by a semicircular movement of the camera. Oliver walking down busy, but lonely, New York City streets after he’s discovered that Jenny is dying. Oliver in the locker room, without Jenny, trying to talk to friends (but sad to be separated from Jenny). In fact, it’s always lonely Oliver, who is shot in a semicircular sweep of the camera that emphasizes the roundness of couples that have been divided into two. Watch this scene: Oliver (and not Jenny) has been informed of Jenny’s death prognosis; he is terrified of what he knows will come. The morning after he’s been told (and after he’s been instructed not to mention the disease to Jenny), Oliver wakes up after a night of sex with his dying wife. We have a cut to Oliver, chest uncovered, in bed. It is dark, but Oliver’s face is lit, and near the center of the frame is a clock. We hear its loud clicking while we watch Oliver stare at the ceiling. The camera comes closer and then moves in a semicircular (and not fully circular) way toward him, as if to hug or kiss him. The clock keeps ticking. His eyes widen, and the alarm clock goes off. He blinks and looks toward the clock. Then the shot is cut, abruptly, and we’re meant to experience some disquiet; the camera is ripping the dying couple apart here. There is a sudden shot to the other side of the bed, this time from the back, and the light is suddenly much brighter. Oliver reaches over and turns the alarm off. He looks over to the side where Jenny should be, but she’s not there! Oliver is as alarmed as the alarm clock just was (Is her time already up? Is she already dead?); he lifts his head and torso quickly from the pillow and calls out Jenny’s name urgently, with panic, as the camera continues to focus on his pillow, showing an empty bed. He keeps calling her, and then there is a cut to an already awake Jenny walking into the bedroom, urging him to get out of bed.

The halving of Oliver serves to underline the loneliness of Oliver; it’s a constant in the film. He starts out the film in a pathetic posture on the bleachers after Jenny has died; we then have the tale of well-rounded Harvard love that we know in advance is tragically ripped apart by Jenny’s death; we have Jenny’s deathbed scene, where the couple clutches each other into her death; and then we return Oliver to his single (but now elaborately tragic) status as someone who has loved and lost. The huge appeal of this kind of love story might be pedagogical: even if you end up as lonely as Oliver does at the end, at least he has a love story to tell. At least he’s trying to make something big and everlasting like a marriage work. Sure, it’s hard work, and it even provokes tears and heartache. Perhaps we’re also meant to learn that Oliver’s kind of loneliness is an inevitable punishment for striving to round himself out by loving another. The pathetic quality of Oliver becomes a kind of encouragement: we don’t want to be in that position, that place of loss (even if our choices will lead us there nonetheless). But we have no reason to expect that Oliver will stay lonely and alone in that park forever. After all, he falls in love very easily (at least with Radcliffe women), and he has the appeal of Jenny’s love of him (and the Beatles) to prove it. There’s always hope in the couple he has had and might still make in the future.

“Love,” writes Plato, “is the name for our pursuit of wholeness, for our desire to be complete” (29). It’s supposed to be a source of sustaining optimism. Yet in the next breath, Plato has Aristophanes remind us that this pursuit, this love, is also a reprimand: as I’ve been explaining, the gods were punishing the strong creatures by inflicting terrible acts of division — dividing beings and then making them couples again. Love, indeed, will tear us apart, again (and again).7 But this pursuit of your other, better half is not merely a refusal of or rebuttal to the original punishment. It’s a desire that has been implanted in us by an ideology of the couple that will help us cleave together in a lonely and deadly way. It’s a terrible twist that even Plato’s Aristophanes can’t make entirely sanguine:

Long ago we were united [as amalgamated beings] as I said; but now the god has divided us as a punishment for the wrong...