![]() The Emergence of Air Pollution as a Problem

The Emergence of Air Pollution as a Problem![]()

1

Perceptions and Effects of Late Victorian Air Pollution

Peter Brimblecombe

A general problem of environmental history is to understand the relationship between the effects of environmental pollution and its social perception. Some have argued that environmentalism arises as a response to environmental stress (e.g., Pfister’s 1950s syndrome), while others have felt that pollution is probably a necessary disposition but not a sufficient reason for changing perceptions of the environment. The subtitle to this book reminds us that we cannot ignore that the perception of pollution takes place within the broadest social context.

This chapter examines the air pollution in late Victorian cities and explores both its effects and its social and administrative perceptions. These perceptions affected the way in which the earliest coherent legislation began to develop and may ultimately have affected the strength of the response to air pollution in English cities. A historical look at the emergence of air pollution as a “problem” draws attention to the complexity of our environmental perceptions.

Air Pollution during Industrialization

Air pollution has been recognized from the earliest of times, with perceptible odor an issue in the cities of ancient Egypt and smoke of concern to Roman administrators and lawyers. However, this recognition tended to lead to ad hoc responses rather than a strategic and coherent approach to the regulation of early air pollution problems. Indeed, Mieck (1990) has argued that the numerous pollution decrees from the Middle Ages are essentially a response to single sources of what he terms pollution artisanale, as distinct from the later and broader pollution industrielle that characterized an industrializing world.

The need for strategic approaches to urban air pollution grew in late-eighteenth-century Britain in cities such as Manchester, where the steam engine had been adopted with great enthusiasm. The first steam-powered cotton mill in Manchester was constructed by Richard Arkwright in 1782 and occupied a building five stories high and two hundred feet long. By 1800 there were many more, along with furnaces and refineries, which created air pollution problems and aroused administrative concern.

From medieval times, smoke and other nuisance offenses in English cities were usually addressed through the Court Leet. By the 1790s the Manchester Court Leet ceased to exercise effective controls over the growing sanitary problems of the city. Even contemporary writers saw this as an outmoded form of government, and it was especially weakened by the growth of industry beyond the jurisdiction of parish boundaries. This limited options for enforcement and difficulties over defining what reasonably constituted a nuisance. The problem Mieck terms pollution artisanale had been replaced by pollution industrielle.

Manchester was an example of a city that benefited from improvement acts (e.g., 32 Geo III of 1792), which allowed it to set up a new body, the Police Commissioners. The commission rapidly grew in importance from late 1799, as it began to respond to urban sanitary issues. It soon added smoke from steam engines as an issue of concern. Using the powers of the 1792 act, a Nuisance Committee with standardized procedures began addressing the issue of smoky chimneys. Central legislation regarding nuisances from steam engines developed in an act of 1821 (1+2 Geo IV c.41), which led to the Manchester Police Commissioners immediately giving notice to all owners of steam engines that they meet the provisions of the new act. Despite their enthusiasm to abate smoke, the commission’s resolve proved weak.

One important action of the Manchester Police Commissioners was the development of the office of Inspector of Nuisance. In 1799 the commission appointed a constable to inspect the streets and report on nuisances and offenses contrary to the act of Parliament. By the 1820s these duties fell to Nuisance Inspectors, who reported to the Nuisance Committee. This post became increasingly a part of improving the environment of English towns and cities of the nineteenth century.

Public Health Act of 1875

The notion of sanitary reform formed an important element in the changes of civic administration in the nineteenth century. This is often seen as deriving from the work of individuals such as Chadwick in England but was in fact much broader. Smoke abatement cannot be separated from sanitary reform in the nineteenth century, because so much of the legislation about smoke abatement occurs within UK sanitary legislation. In Britain, legislation on this matter abounds in Public Health Acts (e.g., 1848, 1875), Sanitary Acts (e.g., 1866) and other acts, such as the Towns Improvements Clauses Act (1847). A further connection between sanitary reform and smoke is seen in the development of Nuisance Inspectors, who investigated urban smoke, among other things. They were often seen as an aid to the Medical Officer of Health. Early Medical Officers came from the medical profession, but there was at first no formal training for Inspectors of Nuisance. However, by 1876 the Sanitary Institute set about certifying inspectors and developing professional competence. Such qualifications were not compulsory, but by the late 1880s many urban districts had highly qualified inspectors and professionalism rapidly became desirable in applicants for posts.

The work of the Sanitary Inspector was directed by the Medical Officer of Health, who often focused on disease and thus viable entities in the air. Medical officers often worried about smells, effluvia, and general aspects of domestic sanitation. In general, they were less concerned about the inorganic constituents of smoke; indeed, these, especially sulfur dioxide, were frequently perceived to be disinfectants.

There was a further problem for the inspectors. The activity and agitation over smoke in English cities in the earliest decades of the nineteenth century appear not to have lessened its spread. This is true even of a city such as Manchester, which had tried to reform the way in which it approached this nuisance. There were economic forces that constrained councils to bend to the will of industrialists, but administrative and technical difficulties were also important.

It was not until the Public Health Act of 1872/1875 that there was a more uniform approach to the smoke problem throughout England. The transitions of the 1870s were thus very important. Sanitary officials and, importantly, the Medical Officer of Health became compulsory positions. The appointment of these officials was not regarded as a trivial matter, and the city of York was chastised for attempting to appoint the Chief Constable (rumored to have vested interests in local industry) as the Inspector of Nuisance.

A growing group of talented and enthusiastic professionals began to emerge in towns and cities throughout the country. They addressed a wide range of public health issues, from adulteration of food, to the state of the sewers, to working conditions in factories, to air pollution matters. The profession began to include women, to some extent prompted by the need for access to domestic premises and factories dominated by women. The earliest appointment of women provoked considerable discourse between the civic administrators, the Local Government Board, and professional organizations. The involvement of women in the profession had the potential to bring new perceptions of smoke to bear. Most particularly, women were seen as guardians of morality in Victorian society, which often led to an equation between sooty deposits in the city and “moral dirt.” Domestic activities such as cleaning and washing had to confront the realities of smoky air on a daily basis.

The activities of Sanitary Officers and Nuisance Inspectors failed to stop a profound deterioration in the environment of many cities through the late nineteenth century. However, it would be wrong see no value in their work. They can be seen pursuing the most difficult of cases against large and powerful industries. The daily logs of these inspectors and the reports in Council Minutes indicate in many cases considerable effort in difficult circumstances and a developing sense of professionalism.

Air Pollution in the Late Nineteenth Century

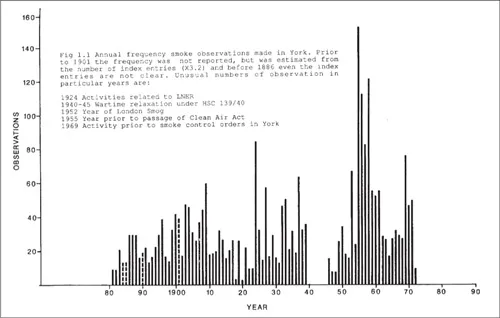

It is difficult to get an objective picture of air pollution in late-nineteenth-century cities. There are many vivid descriptions from writers, but the lack of measurements is an important issue. In particular, it creates a problem among both contemporary administrators and historians in assessing the impact of regulation. It was not that nineteenth-century inspectors didn’t wish to analyze progress; rather, they had little understanding of how this would be done. Urban air pollution monitoring networks did not really begin until the development of deposit gauges, inspired by work of The Lancet in 1910. In the documents left by early inspectors, they seem keen to assess progress by counting the number of times smoke was observed each year (see Figure 1.1). Such observations tend to relate to activities initiated by the administrators, but the administrators did not seem to confront the fact that this did not reflect the amount of pollution.

FIGURE 1.1. Number of Smoke Observations Made in York, 1880–1972

Thus sanitary inspectors did not take measurements of the concentration of air pollutants and relied on visual observations. They did not possess the skills to undertake analyses of the atmosphere, and textbooks of the time show that it was not part of their training. Nevertheless, the paucity of air pollution measurements is somewhat surprising given the importance governments gave to scientific approaches to some pollution issues, such as contamination of rainfall and river water and even compliance with the Alkali Acts of 1863. The Alkali Acts required manufacturers of sulfuric acid to limit their emissions, which were to be measured through chemical analysis. Britain was fortunate in its choice of the first Chief Alkali Inspector, Robert Angus Smith. He was responsible for many early chemical analyses of the air and rain, and his interests always went far beyond the requirements of the act. A few others, notably W. J. Russell, privately undertook analyses in London in the 1880s. The accuracy of measurements of urban air quality of the nineteenth century is difficult to assess, however, and measurements frequently appear to be unreasonably high.

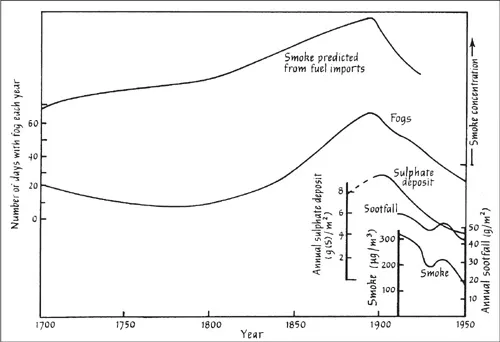

It is also possible to estimate the concentration of air pollutants through modeling. This has been done using only the simplest of models, but it suggests that air pollution concentrations were high at the end of the nineteenth century. This is supported by a strong similarity between fog frequency observed in London and modeled pollution load. This is expected, as the pollutants from coal burning can enhance formation of fogs.

There is evidence that fog frequency declined in London from the early part of the twentieth century, and crude models would agree that the total load of pollutant smoke and sulfur dioxide may also have been on decline. As difficult as the early London monitoring data is to interpret, it doesn’t discount the idea that air pollution load may have been highest about 1900 (see Figure 1.2). It is more difficult to establish such patterns for other cities, where there are less data. In all probability the maximum in air pollution occurred later.

Fin de Siècle Cities

In spite of a developing body of legislation, there was considerable gloom about improvements in the sanitary state of cities by the end of the nineteenth century. Estimates of the pollution from modeling work suggest that it could well have been at its worst in Victorian London. Sanitary inspection had developed as a profession, yet there was a lack of a central power to help force improvements. A fragmented local structure characterized an administration very different from the national sway exerted by the Alkali Inspectorate. This meant the centrally administered Alkali Act may have had more force than the localized approach to regulating general urban air pollution matters.

Despite a sense of ineffectiveness to the control of urban smoke, the individual Sanitary Inspectors’ hard work sometimes led to a perception that they must be having an effect. There was no doubt a certain amount of posturing in local claims that things were getting better or worse. In some areas of Manchester it was said there had been so much local improvement that it was smoke drifting in from industries of neighboring authorities that was becoming a problem. In another case it was claimed that while a “steady improvement in the diminution of factory smoke is undoubtedly being obtained … there is considerable room for improvement.… What is greatly wanted in this matter is a higher public conscience; it is difficult otherwise to obtain improvement, as repeated prosecutions are burdensome and sufficiently heavy penalties appear to be impracticable.” Recognizable achievements in the short term tended to be small or rather specific, so a gloomy prognosis was understandable.

FIGURE 1.2. Predicted Smoke Concentration and Observed Fog Frequency for London, 1700-1950, Compared with Shorter-Term Measurements of Sulphate and Soot Deposit and Smoke Concentration

Improvements appear not to have come swiftly through the adoption of a given piece of legislation. They seem more an outcome of continual pressure on industry, which gradually caused it...