![]()

1

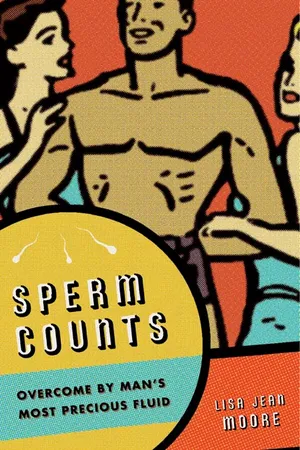

In the Beginning, There Was Sperm

It has been called sperm, semen, ejaculate, seed, man fluid, baby gravy, jizz, cum, pearl necklace, gentlemen’s relish, wad, pimp juice, number 3, load, spew, donut glaze, spunk, gizzum, cream, hot man mustard, squirt, goo, spunk, splooge, love juice, man cream, and la leche.1 I refer to the tacky, opaque liquid that comes out of the penis. Such a variety of words suggests at the very least the variety of uses and effects of sperm. As sociologists, of which I consider myself one, would be quick to point out, the very act of defining “sperm” and “semen” depends on your point of view, or your standpoint. That is, how sperm comes to be known is based on who defines it (a scientist or a prostitute), under what social circumstances it is found (at a crime scene or in a doctor’s office), and for what purposes it will be used (in vitro fertilization or DNA analysis). As with its variety of names, sperm’s meaning, like the substance itself, is fluid.

Yet however numerous the meanings, all sperm originates in the male body. As such, our prevailing ideas about men and masculinity are used to measure and evaluate the relative social value of sperm. This is particularly relevant at this historical moment, when the rise of sperm banks has given greater access to sperm than ever before. I would argue that this increased access, alongside a much more public presence of sperm in everyday life—think of “the stain” on Monica Lewinsky’s dress or the numerous references to checking for DNA through sperm samples as reported in the news media—is being experienced by some as a threat to the power that men have traditionally wielded just by the very nature of being men. While there have been crises of masculinity throughout history, the fact that sperm can now be manipulated outside of men’s bodies, can even be bought and sold like other commodities, can be tested and used as evidence in crime cases, and can be used for conceiving a baby with essentially no strings attached to the actual originator of that sperm (that is, the man), the crisis is exacerbated as never before.

POLYSPERMOUS: SEMEN IS EVERYWHERE

The bombardment of images, news stories, and scientific rhetoric about semen can sometimes seem overwhelming. Semen can be represented as engendered, malleable, agentic, emotive, instructive, sacred, profane, entertaining, controversial, empowering, dirty, clean, normal, abnormal, potent, impotent, powerful, incriminating, anthropomorphic, uniform, polymorphic, and deterministic. Even though semen is diversely, even contradictorily, represented in the preceding list of terms, the meanings of semen are deployed, on the whole, to reinforce a sense of virile masculinity. These macho representations of semen enforce ideas about the differences between men and women, in terms of both their gender and their sexuality.

This hypervisibility of stories about semen reminds us that, of course, these cells are integral to human life, but they are something more, too. They are “little soldiers,” the “liquor of love,” and “mighty troopers.” A New York Times Magazine cover story in March 2006 entitled, “Wanted: A Few Good Sperm,” detailed the trials and tribulations of a number of single Manhattan women who had decided to conceive through sperm donors. These “single mothers by choice” are “tired of waiting for the right guy to come along” and instead are “just looking for the right sperm.”2

A quick survey of various media from the summer of 2005 illustrates other seminal overload. Summer books were full of sperm. Brooke Shields’s postpartum depression memoir, Down Came the Rain, fueled by a feud with Tom Cruise, climbed the bestseller lists. In the book, Shields, struggling with infertility, laments the fate of her husband’s body fluid in her vagina: the “little spermies couldn’t swim upstream” because “the poor guys have been jumping into a pool with no water.”3 (Ironically, Shields and Cruise’s partner, Katie Holmes, would both give birth on the same day in the same hospital a year later in the summer of 2006, proving that the “spermies” did eventually swim to their target.)

Slate deputy editor David Plotz’s book The Genius Factory: The Curious History of the Nobel Prize Sperm Bank received rave reviews from many prestigious newspapers.4 In this account of the Repository for Germinal Choice, which existed from 1980 to 1999, Plotz traces the creation of a sperm bank that used only Nobel Laureates as donors. Their mission was to save the gene pool by preventing genetic degradation and curbing the production of “retrograde humans.” Interestingly, though, the female recipients of the prized sperm did not necessarily need to be Nobel Laureates or deemed equivalently elite. In any case, after nearly two decades, competition from other sperm banks and its own decreasing popularity compelled the Repository for Germinal Choice to close up shop. Even genius sperm sometimes can’t swim.

Sperm stories also regularly pop up in newspaper headlines. Stealing a glance at the New York Post on the subway on July 25, 2005, I was drawn to a headline: “Pop Shock: EXCLUSIVE—Dad must pay for ‘secret sperm tot.’” I inched closer to the paper through the throngs of people and read, “A Brooklyn man says his estranged wife forged his signature on a form to get his frozen sperm—and then used it to conceive his daughter. He was ordered to pay child support—and now he’s filed a $9 million suit naming his wife and the fertility clinic as plaintiffs.”5 Later that week, I read an article by Katha Pollitt in The Nation in which she underscored the ironies of pharmaceutical funding, research, and distribution of contraceptive and sexual drugs; she exclaims, “Viagra is pro life, the Pill is pro death—sperm rules!”6 An August 1 report on CNN recounts the all-too-familiar story of a man, Thomas Doswell, released from prison after 19 years for a rape he didn’t commit: “When the tests came back last month showing that semen taken from the victim was not from Doswell, prosecutors filed motions to vacate his sentence and release him.”7 The relieved Doswell is shown embracing his family. No mention is made as to who the sperm actually came from.

Newspapers regularly report in their science sections on research studies of animal sperm competition that might explain the actions of human sperm. According to a July 2005 BBC world service report, to test the effects of microgravity on sperm, China plans to send 40 grams of pig sperm to outer space. Upon return to Earth, the astro-sperm would be used to inseminate female pigs. A New York Times article, “Sex, Springs, Prostates and Combat: New Studies, Better Lives,” cites an experiment on heterosexual men between 18 and 35 who are asked to ejaculate after being exposed to images of competitive sexual situations.8 The volume of their ejaculate is then measured to see if competition triggers greater seminal production. The implication is that if men produce more ejaculate (and therefore more sperm) when they feel competitive in sexual situations, this feeling will increase the likelihood of successful insemination. The dubious extension of this hypothesis is that sexual competition is rewarded in the process of natural selection.

Not to miss a sensational opportunity, the WB, the now-defunct teen television network, aired a new sitcom midseason 2005/2006 entitled Misconceptions. The promotional blurb states:

Jane Leeves (Frasier) is Amanda Watson—smart, sophisticated, and a little out of touch with her 13-year-old daughter, Hopper. Amanda was ready to buy Hopper an iPod for her birthday and was shocked to find out that all she really wanted was to meet her biological father. Why wouldn’t she? He sounds amazing. Hopper and Horace, Amanda’s best friend (French Stewart, 3rd Rock from the Sun), have heard for years how this mystery guy is Ivy League-educated, well bred, handsome, incredibly athletic, and a successful doctor. The only problem is, Amanda doesn’t actually know him. She only knows him as #431 from The Ivy League Sperm Bank and the profile that she had been given.9

Always looking for new story lines, clearly the television network sees the inherent dramatic possibilities of sperm banks. Although it was promptly cancelled, NBC also produced, Inconceivable, a show that followed the travails of a fertility clinic where an animated sperm cell popped up to introduce the on-screen chapter titles.

In television shows, news stories, and scientific studies, certain sperm stories are repeatedly played out. These stories are emblematic of how we come to know and understand sperm and men. The commonality in each story is that sperm are essential to human life. Similar to the story of Viagra, sperm have journeyed from the realm of the secretive to the realm of the communal. Just as it used to be taboo to speak about impotence, we now seemingly can’t stop talking about the stiffness of penises (“Erections may last four hours,” as one commercial warning notes) or the ejaculate that forcibly explodes from them.

Yet while sperm may reign supreme, arguably we live in a moment where traditionally defined masculinity can be seen as weakening. With the rise of the “metrosexual,” the professional sports steroids scandals, the outing of impotence with the success of Viagra, the mainstreaming of shows like Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, and the arrival of even the gay cowboy with the film Brokeback Mountain, American popular culture continues to challenge a monolithic but oft-celebrated “rugged” heterosexual masculinity. As our ideas about men and masculinity change, our ideas about sperm—specifically, its power and value—also shift. I contend that at this moment sperm have increased visibility as never before.

Although sperm has been defined differently over time, particularly as science and technology advance, sperm as a substance has also become more malleable and flexible (or fluid) than ever before. For example, we can do more things with it—count it, capture it, dispense it—than we could 20 years ago. Sperm are still represented as strong, fast, crafty, resilient, competitive, and long lasting, as men often are, yet the confidence in those ideas seems to be eroding with technological advancements and with changes in societal mores. Sperm now have the power to convict or free men, identify paternity, and fertilize in perpetuity—enabling men beyond the grave to father children. It would seem that sperm has a life of its own. Yet all of these technological advancements have, ironically, given more power to women than to men, as women can now control and be protected from sperm in ways that were previously not available. As New York Times writer Jennifer Egan put it in a recent article, “Buying sperm over the Internet . . . is not much different from buying shoes.”10 With men losing control over the very substance that many would say defines them as men comes a rather unsettling state for men and manhood, with many questions left unanswered.

DIVING IN: FOLLOW THAT SPERM

Interested in these ironies, in this book I explore the power and complexity of semen. Using a “follow that sperm” approach, I first trace the historical journey of sperm from its fabulous Western bioscientific discovery to its war-weary travails in the vaginal crypt. Attaching my analytic lens to sperm itself provides interesting perspectives on how sperm “is spent” and is reabsorbed, as well as how it swims, spurts, careens, and crashes through ducts, penises, vaginas, test tubes, labs, families, cultures, and politics. Examining the science of semen historically and culturally, I show how scientific representations of sperm and semen change over time. Much like the fluid of semen itself can leak onto different fabrics and into different bodies, the meanings of semen are able to seep into our consciousness. How does sperm relate to manhood? What does it mean to be a “real” man? A “real” father?

In a sense, this book’s analysis reveals how “sticky” or messy and complex masculinity is in the 21st century. I see sperm as a metaphor for contemporary masculinity: it is both valorized and reviled, representative of life and death. Yet despite its “fluid” quality, sperm is always already essentialized and relied on to tell the story of masculinity in many social arenas, including family, law, science, and the sex industry. Through these stories, as with any concept, sperm becomes institutionalized and taken for granted and, thus, self-sustaining.

My work expands on previous scholarship by analyzing how sperm is a “liminal substance” that traffics between biological and social worlds. That is, sperm is both a material and a symbolic entity, is a part of both nature and culture, and has scientific and social value. For example, anthropologist Emily Martin, in her groundbreaking article, “The Egg and the Sperm: How Science Constructed a Romance Based on Stereotypical Male-Female Roles,” showed that there is no “objective and true” knowledge about fertilization by revealing the ways in which scientific knowledge is always socially and historically situated. Martin shows that the tropes of biological textbooks reveal the cultural beliefs and practices enacted in these suggestive images: sperm are strong, eggs are passive. In this book, I build on Martin’s concerns about the power of metaphor in science to keep “alive some of the hoariest old stereotypes about weak damsels in distress and their strong male rescuers.”11

Drawing on 15 years of research, Sperm Counts interprets the many meanings of semen in the 21st century. I examine historical documents from biomedical and reproductive scientists, children’s “facts-of-life” books, pornography, the internet, forensic transcripts, and sex worker narratives. I also base the observations in this book on the time I spent doing research in sperm banks and interviewing executive directors, board members, lab technicians, and recipients—the elusive ethnographic work mentioned earlier.12 Understanding how we biomedically, socially, and culturally produce, represent, deploy, and institutionalize semen provides valuable perspectives on the changing social position of men, male differences, and the changing meaning of masculinity.

Ultimately, sperm is not involved only in the physical reproduction of males and females but in how we come to understand ourselves as men and women. The ways in which we choose to manage and assign meaning to sperm indicates the recalcitrance of our stereotypes about gender. This gendered social order is both reinforced and destabilized by the meanings assigned to semen and the manipulation of sperm’s potential.

THE MASCULINE HEGEMONY

Sociologist R. W. Connell has coined the phrase “hegemonic masculinity” to explain the inherent variations of masculinity.13 He argues that hegemonic masculinity involves not only the domination and exploitation of men over women but also the domination and exploitation of certain kinds of men over other men. This is accomplished, in part, by instituting an “ideal type” of masculinity—that is, strong, aggressive, physically dominating, wealthy: tough men like Arnold Schwarzenegger, Ted Turner, and Michael Jordan. Today our understanding of masculinity is based on physical power, brute force, rationality, and controlled emotion. This is a hollow image, based on cultural icons that do not reflect the reality of most men’s lives. Nonetheless, this ascendancy of a “man’s man” is supported by social structures in which the concept of masculinity is embedded: religion, politics, and popular culture. For example, heterosexual, white, upper-middle-class, reproductive, serially monogamous men are situated “above” women and other types of men—homosexual, men of color, working-class, nonprocreative or sterile, nonmonogamous, and “perverted” men. Think George Clooney over George Costanza.

The power of the sciences to naturalize social relations is considerable because of their privileged position to offer “official” knowledge about our understanding of gender and sexuality.14 Guided by feminist theory and masculinity studies, I examine how gender emerges from various representations of the “natural” fluids of men that, in turn, produce a “natural gender order.” Gender is represented in scientific literature by relying on tropes and metaphors from fables, traditional stories, and familiar imagery.15 I view sperm and semen representations as symbols of different types of masculinities. As a symbol of conception, sperm can be seen as a fierce competitor winning the conception race, a benevolent father laying down his life for creation, or an absent-minded professor bumbling his way as he is shuttled through passageways. As a symbol of infertility, sperm can be seen as an impotent wimp unable to sustain himself in the acidity of the vagina, while semen banks represent sperm as a good catch embodying all the desirable traits of humanity. A forensic representation casts sperm as a masculine threat overcome with animalistic passion that triumphs over rationality and decency. The representation of sperm in a paternity lawsuit might suggest a liar who strays from his faithful wife into the arms of another. A pornographic representation portrays sperm as a hunk of burning love for the insatiable appetite of oversexed women.

While these notions of masculinity as represented by sperm exist in real-lived human experiences, these representations are also ideal types of masculinity begging for a performance. Thus the meaning of masculinity is not concrete, consistent, and fixed; rather, since our own actions, or performances, of masculinity and femininity are ongoing, these representations are fluid and change depending on the circumstances. Although they are sometimes unintentional, the images or representations are meant to instruct or incite actual men and women. That is, there is traffic between the ideal type of masculinity and the performance of being masculine that is often assumed.

The ranking of men through masculinity creates an inherent and ongoing competition for the singular top position. Male-dominated institutions, like the medical industrial complex, biological or scientific enterprises, and the criminal justice system, often pit men against one another in their pursuit of this dominance. Men there are engaged in practices of representing other men as flawed, unworthy, or immoral. In forensic science, for example, men (and women) investigate seminal stains to prove the flawed character of other men. The sperm cells themselves can often be imbued with masculine attributions and foibles.

LEGITIMATE MASCULINITY

While researching sperm, I have been intrigued by the changing role of men in our ...