![]()

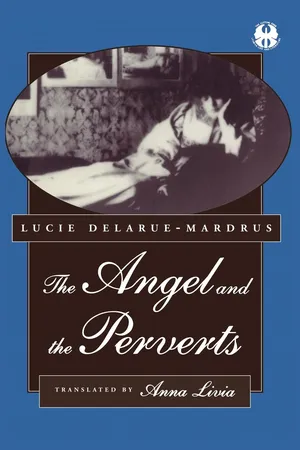

The Angel and the Perverts

![]()

[ I ]

He often dreamed that his mother, or rather the blind beast which works within us independently of our minds, had been expecting twins while she was carrying him, for, ever since the age when human beings enter into the agony of the soul, he had felt instinctively at his side a mysterious second self.

The fine lady with the reticent eyes, who carried the distinction and stiffness of her race in her very marrow, insisted from the cradle onward that she alone would look after the sickly creature she had brought into the world. She never left the child in the hands of an underling, even for a minute. A rare quality for an Anglo-Saxon woman, especially one of high class. Later she continued to wash, dress, play with him, and put him to bed without any help from a nanny. It was from her he learned his first prayers, and to read, write, and count in English and French.

In France at least this would suppose the most intense tenderness between mother and son. But the dry kiss with which the tot was greeted each morning and sent away each evening was enough to maintain a terrible distance between them. The formality of playtime was chilling:

“Play!” Madame de Valdeclare would order.

And if occasionally, on rainy days, she would condescend to play a few games of snakes and ladders, no familiarity accompanied this pastime.

It seems very probable that the father, a hard, taciturn man, imposed such a child-rearing system on his wife, terrorizing her into the bargain. It was clear that he fled the sight of his only offspring, in whom he inspired a monstrous terror. A hostile stranger would not have looked at the poor child with greater malevolence.

Occasionally the boy would be taken for a drive in the car Hervin de Valdeclare used to visit his farms, or to journey as far as Paris where he had business with various lawyers. As they passed through endless plains of beetroot, which none of them bothered to look at, the child would cling to his mother and keep his head stubbornly lowered to avoid glimpsing the face of the gentleman with the long moustache whose son he was.

The first abbé to come to the château, an arrogant old ecclesiastic brought back from Paris after a short business trip, did nothing to alleviate the régime to which one of the gentlest little boys on earth had been subjected.

So be it. All parents are distant and suspicious, all priests toothless and surly, all children treated like guilty prisoners.

Both delicate and hardy, the little boy alternated between his bed and the schoolroom, would catch up a month’s illness in three days. At times they would have to restrain the feverish eagerness with which he learned his lessons and did his homework, while at others he had to be punished for his laziness.

Kept implacably away from other children, he did not even go to catechism lessons when the time came, but received that pious instruction from the abbé. He was forbidden to speak to the servants. He could not play without supervision. The abbé’s reign did nothing to end this jealous surveillance. The slender Englishwoman sat silently through every lesson, accompanied them on every walk. And at night the little lad slept in a small room next to hers.

Deprived of any intimacy with the repressed individuals who peopled his world, brought up on hard work, coldness, and enigma, he turned his gaze toward the void, full of the questions and absurdity of childhood. His great eyes, in which three distinct colors could be seen laid out like a rose window, were shadowed by the prominent ridges of his eyebrows, which stood out upon a forehead rich in intellect.

With his thin fingers and a face consumed by pallor, his whole slender being bore that air of pathos which marks the beauty of the invalid.

“Mother,”1 he would say. Mamma would have been too gentle for this child whom no one loved. No one called him “tu.” He had no dog. No cat. His only friend was the unborn double who obsessed and defied him all at once, demonic familiar of this troubled, troubling being.

Since he was never alone, it was only when preparing his lessons for the abbé, or when he was in bed that he could call up the phantom’s presence.

We forget so many of the dreams of our early years and no one is there to record them in time. The visionary creations of childhood, and of some childhoods more than others, would prove to be masterpieces of poetry or fantasy for one who could write them down in a language close enough to their conception.

The little Valdeclare lowered his eyes hypocritically over the page and, speechless, chattered with his mute other, his invisible brother. The games of his imagination whirled around inside his head, veritable creations in which the genius of those tender years overflowed. The delights, quarrels, and poetic enthusiasms of his imagination caused such a range of expressions to pass over his absorbed countenance that his mother would ask in alarm, “What is the matter, Marion?”2

She pronounced it “Marion,” an English name which can be used for either sex. The little boy would jump, woken with a start as though from sleep. No plausible explanation came to mind. He had been bent over an arithmetic problem! He would look fearfully at the woman sewing on the other side of the table who was secretly watching him. Quickly he would improvise: “I was thinking about Monsieur l’abbé. He nearly fell over yesterday when he was throwing me the ball. Didn’t you see?”

But he hated that ball, officially sanctioned recreation with no room for the fantastic or the intangible. He had been given it the previous Christmas instead of the doll he had asked for. Nor was he allowed to cut out figures in gold and colored paper. He got no pleasure from a wooden puzzle or a little mechanical car. The only toy he enjoyed was an old kaleidoscope which had been in the family for years. He was amazed to the point of terror that they let him vanish into that little fairyland. “If I look into it too often, they’ll take it away from me.” He did not realize what a martyrdom his childhood was. He would have liked to hide away so he could play with the marvelous toy, feeling as though he were doing something forbidden. But there was nowhere to hide.

His favorite ritual of the day was going to bed. It was true his mother could see him from her bedside, her eyes burning in the shadow of the nightlight. But, turning toward the wall, he experienced a moment of inexpressible release. He was two once again, and he smiled at his brother. Unfortunately he would doze off too fast. But before slipping into that end of everything which we call sleep, he had time to confide his secrets. One baby word remained in his private vocabulary. He would list the day’s sorrows:

“Bobo,3 the story of the unlearned lesson . . . Bobo, the story of playing ball when I didn’t want to . . . Bobo, the story of Father on the stairs . . .”

And, on certain evenings, this cry of utter despair, “Bobo, the story of everything!”

As he grew up, he stopped dreaming so much and threw himself into his studies. At fourteen he wrote Latin poetry as though it were child’s play, knew several plays by Racine and Corneille by heart, was beginning integral calculus, polishing up his knowledge of botany, had started astronomy, spoke fluent English, and was reading the German poets. They had had to find a new abbé. One after another his successors gave up on this all-consuming pupil.

“He’ll become a Benedictine!” they would say in alarm.

The first time this word was spoken, Marion witnessed a miracle: a smile on Madame de Valdeclare’s tight lips.

A little later she asked him what his intentions were. If he wanted to go to the seminary, they would not stand in his way.

At table his father went so far as to address him directly.

“The best thing you could do would be to become a priest!”

He made no reply. He so seldom spoke! Then a veritable siege began around that adolescent boy. The abbé, the village priest for whom he’d been serving mass for the last six years, his mother, even his father all clamored:

“Seminary! Seminary!”

But the daily surveillance grew worse, not better.

He endured it as he had when he was little, but now he felt himself to be superior to that old Protestant woman, the shrunken figure whose hair was already grey, who went on sewing soundlessly amid his books, gentle tyrant with an English accent. Whenever he lifted his eyes to her face, she would turn hers away. Sometimes he would throw back his seraphic head and watch her without speaking. A moment’s silent insolence. Embarrassed, she would cough and in a voice which became more and more hesitant, would ask, “What is the matter, Marion?”4

But he no longer even deigned to reply.

Fifteen years old. His sinister childhood was over. He was about to enter the age of independence. He was impatient for the day when cowardice would yield to manly vigor. What shame it was to feel so timorous!

He tried obsessively to catch glimpses of himself in the mirror, would feel his hairless upper lip furtively. The first hairs of his moustache would be a signal for revolution throughout his being. His heart beat fast at the idea.

“We’ll let them see what men we are!” he boasted nightly to his shadow twin.

For his father he felt a most particular hatred, that maleficent idler forever locked away in his useless office.

“The seminary will be our escape route from this house. Then he’ll see! And the abbé? . . . And Mother?5 What will they all say?”

He laughed into his pillow, the solitary laugh to which he had been condemned, a sickly mirth that he stifled as though it were indecent. And suddenly the laugh would stop, a sigh too big for him would fill his throat.

“Bobo, the story of the moustache which will not grow!”

Then, suddenly, death.

The first day that she took to her bed, Mother6 called for her son.

This had happened before. He would then have to work at her bedside for as long as she was laid up. The abbé, who could not enter the room, would wait until she was better before resuming his lessons.

But the abbé did not wait. He packed his bags and fled one morning as soon as it was announced that she had influenza. He had heard this was infectious, which it was indeed.

Seeing two diamonds in the dying woman’s eyes, Marion bent over the bed. Mother7 took hold of his hands and grasped them in hers, moved by an extraordinary force. He heard her utter, “My poor poor child!”8

Remorse at last! Tenderness in extremis!

For the first time in his life he cried out, “Mamma!”

But she was no longer alive to hear it. Lost in death and incomprehension he turned toward his father standing motionless at the foot of the bed and caught his look of hatred. The man’s lips moved, “You have made her suffer enough, the poor woman.”

“Me?” he exclaimed with a sob.

Two figures in black in the over-large dining room: father and son having a tête-à-tête.

“I cannot look after you. Your mother needed to be here for that.”

“Yes,” said Marion, in tones like a boy’s voice breaking.

“It’s impossible for me to stay here alone. I have to go away, travel abroad. But all the same, I can’t very well send you to the Jesuits!”

“Why, Father?. . . Why, Father?”

Intense hope had just called out to him. Other schoolboys! Oh to get away from the château, from the beet fields! To live!

“Because.”

The grim mouth snapped shut. Silence.

One day he would understand the despair with which his mother had doubtless loved him, an anxious dog guarding her little one against wild beasts—and such beasts!

As he was leaving college—leaving hell—(bearing every possible diploma and without having seen his father again, even during vacation, since the latter had abruptly decided on the Jesuits) he learned that he was an orphan, heir to the northern château which had been bombed during the war, and to what little remained of his family’s wealth.

He had always been alone in the world. He set off bitterly upon the road to life, accompanied by his double, his strange, ill-starred double—the taint of his birth.

![]()

[ II ]

“It’s no use bothering her. She cares for nothing and no one.”

The voice of Laurette Wells remained cool and self-possessed as she pronounced these words, a most ironic expression of anger. She rewrapped her legs in the ermine blanket, pulling it out from under Janine who was curled up at the foot of the bed. Her steely eyes sent out sparks in the moonlight of her bedroom, which looked brighter than ever that evening.

The play of the mirrors, the Venetian chandelier, the great quantities of rare crystal, decked the silhouettes of the furniture and the white animal skins with icicles of reflected light.

A trace of perfume floated in the bluish meanders of the air, drifting up from the third member of the group who was smoking continually. The bare windows, looking out on the garden at five o’clock in the afternoon, were black with winter.

The contralto voice of the woman sitting motionless, smoking a little way off from the others, gave Laurette and Janine a start. It ...