![]()

1

A Crisis of Authority

For the first time since the resignation of Richard M. Nixon more than thirty years ago, Americans have had reason to doubt the future of democracy and the rule of law in our own country.

—Joe Conason, It Can Happen Here, 20071

EACH OF US remembers when the 9/11 crisis began: on the crisp autumn morning in 2001 when two airliners were hijacked and smashed into the twin towers of New York’s World Trade Center, causing mass death and panic in the world’s financial hub. A third airliner crashed into the Pentagon, the headquarters of the most powerful military force on earth. A fourth airliner, aimed at the White House or Congress, fell instead in a field in western Pennsylvania. This was our first digital-age security crisis: a terrible trauma, apprehended instantly and universally. It was a security crisis because it raised a series of questions that related directly to the protection of the U.S. homeland. Were more attacks on the way? Could the nation deter future assaults? If not, were we prepared to respond to the aftermath?

Americans looked to their national government for answers to these questions. This was evident in opinion polls, which showed a remarkable turnabout in the public’s usual perceptions about their federal government. Two weeks after the 9/11 attacks, President George W. Bush received the highest approval rating ever recorded in the seventy-year history of the Gallup poll. According to a Washington Post survey completed in October 2001, 64 percent of Americans professed to trust “government in Washington to do what is right”—a level not seen in comparable surveys since the mid-1960s.2 It seemed that the terrorist threat had impelled Americans to reconsider their distaste for central government.3

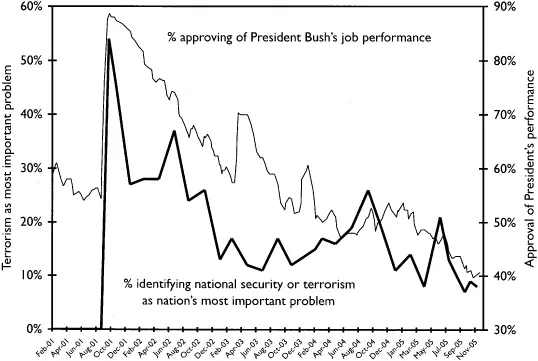

This effect did not last long. At some point in the five years that followed, the 9/11 crisis ceased to be a security crisis. It became something uglier: a crisis of authority. The public’s preoccupation with terror attacks dissipated. By fall 2005, Americans regarded rising gas prices as a more serious social problem. On the fourth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, concern about terrorism did not spike, as it had in preceding years.4 The public’s faith in the president, and in the federal government more generally, waned. Public discourse, at home and overseas, was seized instead with fears about the concentration and abuse of power within the executive branch of the U.S. government.

FIG. 1.1. Concern about terrorism and support for the president. (Gallup poll)

Abroad, sympathy for victims of the 9/11 attacks was displaced by anger at the willingness of the United States to wield its diplomatic and military might with scant regard for its traditional allies or international law. The United States had ceased to be a superpower, as it had been for the preceding fifty years; it was now an hyperpuissance, or hyperpower, according to a French foreign minister,5 or—if one preferred Germanic etymology—the Überpower.6 It had become, for some, the world’s leading rogue state,7 a rampaging elephant,8 a nation that had declared a war on law,9 a selfish and dangerous giant,10 an unchallengeable behemoth,11 a colossus with attention-deficit disorder,12 and a simple-minded goliath.13

The point was not simply that the United States was the predominant global power. The complaint was also, and perhaps principally, that there appeared to be no discipline on the exercise of that power. The nation had slipped the restraints imposed by the political and military realities of the Cold War. There was growing agreement, as Francis Fukuyama observed, that “the irresponsible exercise of American power is one of the chief problems in contemporary politics.”14

Comparable anxieties were aired at home, where the Bush administration was alleged to have launched a “rolling coup” against the U.S. Constitution.15 “The biggest story of the Bush presidency,” said Dan Froomkin of the Washington Post, is its “dramatic expansion of executive power.”16 The distinguished historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. lamented the resurgence of an “imperial” presidency.17 The bipartisan Constitution Project warned against the growth of “permanent and unchecked presidential power.”18 The president had run amok,19 said others, executing policies that infringed radically on civil liberties,20 and put the United States on the path to autocracy,21 dictatorship,22 totalitarianism,23 and the Big Brother state.24 The Bush administration was said to have browbeat Congress and the courts—and also the federal bureaucracy, until it was populated by “robotrons [who] just do what they’re told.”25

The president and his allies, said Princeton University professor Paul Krugman, were “engaged in an authoritarian project, an effort to remove all the checks and balances that have heretofore constrained the executive branch [and] create a political environment in which nobody dares to criticize the administration or reveal inconvenient facts about its actions.”26 As the fifth anniversary of the attacks neared, the editors of the New York Times affirmed that we had crossed from one sort of crisis to another:

It is only now, nearly five years after September 11, that the full picture of the Bush administration’s response to the terror attacks is becoming clear. Much of it, we can see now, had far less to do with fighting Osama bin Laden than with expanding presidential power. Over and over again, the same pattern emerges: Given a choice between following the rules or carving out some unprecedented executive power, the White House always shrugged off the legal constraints.27

The Bush administration, through its rhetoric and conduct, encouraged these complaints. The president and vice president believed that three decades of legislative reforms had badly weakened the executive branch, and they often said so. They wanted to restore “a strong, robust executive authority” and exert American influence more forcefully overseas.28 The administration often imagined the American presidency as Gulliver, the giant restrained by the threads of a thousand Lilliputians. Its advisers articulated constitutional doctrines that justified a broader view of presidential power.29 And in the four years that followed 9/11, the Bush presidency pursued policies that tested some of the limits to its authority.

Nevertheless, a broad-brushed complaint of authoritarianism does not fit the facts. In the five years that followed 9/11, the Bush administration also treated the American electorate gingerly, avoiding significant disruptions to daily life or overt infringements of citizens’ rights and delivering a series of popular tax cuts. It operated one of the smallest nondefense bureaucracies in modern U.S. history.30 It handled the business sector just as delicately, refusing to impose mandates that might disturb the rhythms of a market economy. The administration was attentive to the prerogatives of state governments, even on subjects that touched directly on homeland security.

“We’ve been very active and very aggressive defending the nation and using the tools at our disposal,” Vice President Cheney told reporters in 2005.31 As a general proposition this was manifestly untrue. There were many instances when the critical feature of administration policy was, in fact, the refusal to act aggressively and use the tools at its disposal. The Bush administration also encountered practical and political limits to its authority. Congress, although often deferential, could still be roused to take action against executive-branch initiatives. It undertook inquiries when the administration did not want them, insisted on reorganizations that the administration said were unnecessary, and modified or prohibited programs that the administration claimed were essential to national security.

There were other constraints. At critical moments, civil servants and political advisers did not act like robotrons. Instead, they spoke out against rash policies. Attempts to reorganize and coordinate within the federal bureaucracy were stymied by familiar problems of bureaucratic rivalry. The administration was embarrassed repeatedly by disclosures about covert operations and infighting over policy. Hurricane Katrina revealed the continued inability of federal agencies to collaborate with one another, as well as with their state and local counterparts. Still more evidence of the limits on executive power followed. The Supreme Court compelled the administration to reverse its policies on the treatment of suspected terrorists captured during the War on Terrorism. On the fifth anniversary of 9/11, allied forces were mired in Iraq and Afghanistan. Rash talk about the Axis of Evil had been replaced with diplomatic initiatives to curb nuclear proliferation in Iran and North Korea.

Important constraints on the exercise of authority—institutional, political, cultural, and economic—continued to operate in the five years that followed the 9/11 attacks. Furthermore, there is a pattern to these constraints. In 2001, the United States was a highly advanced liberal state, which happened also to be a military superpower. In its internal design, the U.S. system of government reflects a profound ambivalence about the exercise of executive power, even in a moment of emergency. Complaints about the rise of authoritarianism reflected this ambivalence. Indeed, these complaints can be better understood as symptoms of this underlying ambivalence about executive power, rather than as unalloyed statements of fact.

The critical question after 9/11 was how the American polity would manage this ambivalence in a moment of crisis. The answer is troubling. The American system of government, in the form in which it existed in the early years of the new millennium, found it extraordinarily difficult to pursue domestic measures essential to homeland security, and it was easily distracted by military actions that had the effect of exacerbating security threats.

Entrenched Liberalism

The American state is designed on classical liberal principles.32 Its aim is to thwart the concentration of governmental power and maximize individual freedom. As we all know, the writers of the Constitution pursued this goal by splitting public authority among three branches of government (executive, legislative, and judicial) and three levels of government (federal, state, and local).33 The nation is constructed as a compound republic, as James Madison said: power has been divided so that no part of government can dominate another.34 (The political scientist Walter Dean Burnham later said that the Constitution was designed to “defeat any attempt to generate domestic sovereignty.”)35 Not only is authority fragmented within government; governmental authority as a whole is checked in two ways: by the constitutional entrenchment of basic rights for citizens and the refusal to give government an extensive role in the management of the economy.

The degree to which the United States is distinguished by these initial constitutional choices could easily be underestimated at the start of the twenty-first century. After the Cold War it became commonplace to emphasize the extent to which systems of government were converging around the world. In many countries, state planning collapsed and gave way to market reforms, and new constitutions were adopted that promised protection for the fundamental rights of citizens. The twentieth century, Francis Fukuyama has argued, ended with the “unabashed victory of economic and political liberalism.”36

Still, the United States remains a special case, even among established liberal democracies. It is, as Irving Kristol has said, “the capitalist nation par excellence.”37 The United States maintains one of the smallest public sectors in the developed world, with roughly one-third of gross domestic product (GDP) committed to government spending. (In Europe, the proportion is usually closer to half of GDP.) Moreover, the United States regulates its economy more lightly than do most other countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

The United States is usually grouped with other developed English-speaking nations—such as the United Kingdom and Australia—that share a market orientation.38 A strong commitment to the market society, many Europeans say, is the hallmark of the Anglo-Saxon approach to governance.39 However, the United States is an unusual case even among the Anglo-Saxon countries because of constitutional features that contribute to the fragmentation of power. Other English-speaking nations are parliamentary democracies, in which there is no formal constitutional separation between the executive and legislative branches. In parliamentary systems, the executive has more sway over legislators, and over the bureaucracy as well. Several other English-speaking countries are also unitary rather than federal states. Only Canada has an enumeration of rights within its constitution, as the United States does, but Canada’s charter of fundamental rights is newer by almost two centu...