![]()

1

Post-Racial News

Covering the “Joshua Generation”

The earliest reference to “post-racial” I could find in the news appeared in a 1976 Newsweek article about then-presidential candidate Jimmy Carter. The reporter described the Georgia Democrat as one of a small handful of white politicians who were willing to “gamble his future on a new post-racial Southern politics” in the years prior to the major legal victories of the civil rights movement.1 In this context, post-racial politics meant a politics that would emerge when the institutional apparatus of white supremacy was dismantled. The article compared Carter to the character of Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird: clear in expressing his disdain for racism, but also clear-eyed about the limits of his ability to help black people in his community. After this profile of Carter, the term vanished from the news. Perhaps it didn’t catch on then because violent white resistance to segregation was still fresh in the minds of journalists. In 1976, school busing and affirmative action fights were raging in the courts and in neighborhoods throughout the country. It was hard to imagine the South or any other portion of the nation being “post-” anything having to do with race. Indeed, the term didn’t capture journalists’ interest until the nation was on the cusp of electing the first president of African descent. Why and how the term went from a one-time use in a story about a southern white Democratic candidate in 1976 to becoming a regular feature of election year news discourse in 2008 sheds light on the factors that continue to stymie the media’s “national conversations” on race—conversations that usually leave participants and observers frustrated and wanting something more.

As I discussed in the introduction, the emergence of “post-racial” as a buzzword in the media was a result of multiple factors. This chapter focuses on the ways in which news discourses of race in American politics and society adopted the term “post-racial” to describe shifts in demographics and culture which seemed to require a different set of terms than “diversity” or “multicultural” or “colorblind.” When news producers seized upon “post-racial” en masse in the 2000s, it was as if they’d discovered the word they’d been searching for to temper—or end—the contentious debates of the culture wars, when talk about race, pursued in distrustful fits and starts, seemed doomed to fail. This chapter presents a content analysis of post-racial news discourses. First, I tracked the usage of the term from 1990 to 2010 to discern which uses of “post-racial” dominated discussions of race and racially inflected events. While finding that the term was used only minimally in the 1990s, compared to the 2000s, the analysis shows that similar themes accumulated around the term throughout both decades.

The second part of the chapter examines significant surges in use that occurred in the early 2000s, most often in stories about particular individuals and issues linked to African American identities and politics. Specifically, close readings of the articles show that the usage of “post-racial” accumulated around the continued debate over affirmative action, the significance of the civil rights movement in contemporary life, the style and appeal of black politicians as well as multiracial celebrities of African descent, and the fascination with rapidly shifting racial/ethnic demographic data. The term also accompanied discussions of whether pop culture consumption and racial intermarriage are clear markers of an imminent post-racial era, as commentators debated whether “Generation Millennial” would achieve “Dr. King’s Dream” of a society where skin color is of no consequence. The final sections of the chapter draw from a mix of close reading and quantitative analysis of the exponential increase in appearances of “post-racial,” finding that Barack Obama’s candidacy and early presidency drove most of the post-racial talk, usually drawing from the same repertoire of issues and frames as in the earlier periods.

The Rise of “Post-Racial”: The Numbers

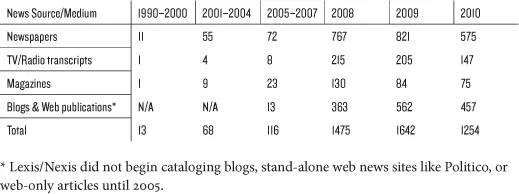

The term “post-racial” is multifaceted and reflects hopes and fears, political calculations and demographic changes. Given the lack of progress in mediated public discourses of race in the 1990s, the appearance and popularity of “post-racial” in the mid- to late 2000s suggests that journalists and their sources found the term an intriguing and useful tool for reframing racial discussions in the twenty-first century. Why did this occur, and why so quickly? First, I conducted a basic content analysis to find out whether use of the term really had increased significantly over the past two decades.2 I was intrigued—and a bit surprised—at how sharp the increase in usage actually was after the 1990s. As Table 1.1 demonstrates, “post-racial” was barely mentioned on television, radio, or in print in the 1990s. By 2008, each of these media—as well as online news—contained hundreds of uses of the term.

Importantly, usage of “post-racial” increased in frequency not just in sound bites from interviewees. Rather, as Table 1.2 illustrates, journalists and editors themselves increased their use of the term in headlines and lead paragraphs of stories in a way that suggests that by 2008, writers and editorial staff were fairly confident that audiences would recognize or be intrigued by the term “post-racial.” The numbers in Table 1.2 tell a clear, if incomplete, story: “Post-racial” became a highly salient term for journalists and commentators across a host of news media outlets by the end of the 2000s. But the larger question remains: How was it being used throughout the period, and why the sharp jump in 2008?

The 1990s: Post-Racial People and Politics—In the Not-So-Near Future

“Post-racial” wasn’t a major buzzword in the 1990s news media; only thirteen pieces used the word, and none in a headline. My close readings of these news items found that all of them employed the term to describe a time in the distant future when racial discrimination will truly be a thing of the past. As journalists looked far ahead to the post-racial dawn, they consistently invoked two interrelated factors that would encourage the development of a post-racial America. First, they proposed that the demographic changes brought about by multiracial people, cultural mixing, and immigration provided a preview of a post-racial society. Second, they posited that at some point, a post-racial politics would displace race-based alliances or strategies.

Table 1.1. News Items with “Post-Racial” in Text or Transcript

Table 1.2. “Post-Racial” in Headline and/or Lead-In of News Items

Post-Racial People: Tiger Woods and Multiracial Families

As golfer Tiger Woods began his meteoric rise in the sports world, many writers argued that his success was proof that golf had overcome its racist, classist country-club history to become colorblind—or post-racial. Others surmised that his success was proof that the United States as a whole had overcome race.3 But Cox News Service columnist Tom Teepen chastised pundits for proclaiming that Woods’s expression of multiracial identity and historic win at the Masters’ tournament signaled that the 1990s were already post-racial. Teepen cited continued racial antagonisms and individuals with less-than-sterling racial records to counter the hype:

Color isn’t the liability it once was, but jeopardies still attach, despite the remarkable number if lifelong racial-justice laggards who are now insisting we’re post-racial. Decry if you will chip-on-the-shoulder multiculturalism, but ethnic jockeying for place is hardly surprising in a nation founded in racial inequality, only a generation past legal segregation, and now trying to fend off Hispanic and Asian immigrants. We’re a ways yet from just enjoying our diversity.4

Other articles pointed to the greater visibility of multiracial individuals and families as a source of post-racial hope. In these pieces, though, multiracial people were portrayed as annoyed and/or oppressed by institutional requirements to articulate to the state their racial identity. The practice of recording and keeping track of racial identity, then, was portrayed as an impediment to a post-racial society, and reinforced colorblind discourse. One columnist remarked on the increase of multiracial and white college applicants who declined to indicate their racial identity. He reported that one college official believed that “the surge in Declined-to-state-ians may be because the race category on the new, post-racial preferences university application form is harder to find and fill out.” Then he joked, “Wait a minute. Is she saying Declined-to-state-ians are lazy and stupid?”5 The attempt at humor gestures toward racial stereotypes of black and Latina/o students that can get into college only via affirmative action—that is, race-conscious policy—not on “colorblind” merit alone. Thus, “racial” thinking was implied to be an outgrowth of keeping official records of racial identity, a practice considered suspect by the writer. These pieces framed the validation of group racial identities or political organizing around the shared identities as anathema to a post-racial future. This theme also surfaced in reports on the possible emergence of a post-racial politics.

Post-Racial Politics

As writers toyed with the idea of a post-racial politics, they did not provide many examples of political practices or policies that would encourage further progress toward a post-racist America. Rather, “post-racial” politics meant black candidates would be able to count on white voters to support them at the ballot box. For example, in a discussion of a 1999 Supreme Court ruling that struck down a race-conscious congressional districting policy, an interviewee on National Public Radio cited data that showed white Democrats were still likely to cross party lines to avoid voting for black candidates. The guest, political scientist Ron Walters, concluded, “We’re not living in some post-racial age in the ballot box yet.”6 He and other guests noted that the (misnamed) “Bradley Effect”—that actual white voting rates for black candidates are lower than pre-election polls suggest—was still a considerable hurdle. But fickle white voters weren’t the only impediment to post-racial politics in 1990s news: The motives and strategies of black politicians were also roadblocks.

A feature on city council candidates in Dallas described the workings of an old-guard black political machine, led by council representatives like Roy Williams, who was described by reporter Dan Schutze as someone who can “intone some of the time-honored maxims of racial politics as though he were playing a cathedral pipe organ.” Then, he contrasted Williams’s style with up-and-coming candidates who hailed from a variety of racial/ethnic backgrounds.7 As the reporter followed the challengers and the incumbents to public appearances, he framed the voters’ choices as follows: between black politicians who fought a good fight against (now insignificant) white discrimination, but now merely rest on their laurels and black voter support, on the one hand, and new politicians who garner support based on their willingness to solve substantial urban issues and not just talk about race, on the other.

People here this evening pay respect to [Roy] Williams. … But it’s history. Everybody has seen African American council members on TV giving white folks hell down there for decades. But how about some new curbs? How about something we can see, something for which there are no excuses? Welcome to the era of post-racial city council politics.8

This description of dysfunctional black urban politics neatly illustrates what became a dominant theme in the 2000s: “Racial politics” are practiced by (mostly black) corrupt leaders who play on white racial guilt and stir up racial anger to keep people of color loyal. Indeed, this racial strategy is so effective, the argument goes, that voters look the other way when elected officials fail to deliver better outcomes. Thus, “racial politics” are a destructive game, pitting insiders versus outsiders in a game that benefits only the politicians. In this and other articles, little is said about instances of interracial cooperation, let alone decades of white racial political practices that deprived black people of voting rights. Thus, “race” is attached to the political practices of people of color, and white racial politics are absent.

Although the reports I’ve described so far refer to Democratic politicians, Republicans also began to craft their own version of “post-racial” politics. Two issues framed conservatives’ approach. First was the need to change the GOP’s image as a mean-spirited, anti-diversity party. This image was heightened during the conventions of 1992 and 1996, where, despite the presence of Condoleezza Rice and Colin Powell, the lasting afterimage was that of speakers such as Pat Buchanan, who called for the end of affirmative action, exclusion of gays, draconian treatment of undocumented immigrants, and so forth. After losing yet another presidential election to Bill Clinton in 1996, Republicans were advised by conservative writer Noamie Emery to reframe their policy proposals and tone down their rhetoric to better appeal to conservative black and Hispanic voters. In a special issue of the New Republic devoted to strategizing how to gain conservative majorities again in the United States and the United Kingdom, she suggested that Colin Powell was the perfect symbol to attract a center-Right group of non-white voters. She also optimistically predicted that the GOP could both narrow the gender gap and grab “20–40 percent of the blacks.” But to do so, she said,

conservatives should learn to reframe their issues. … They should take the lead in the country to a trans- and post-racial future, now that the liberals have formally endorsed the ideas of identity, grievance, and victimhood that have made the West Bank, Bosnia, and Northern Ireland such wonderful places to live. … They should urge that the country drop all racial classifications from the national Census, a sign that the country relates to its people as citizens, not interchangeable members of blocs.9

Here, Emery outlines how the Republicans should use post-racial people (Powell) and policy prescriptions (end collection of racial data) to persuade black and Latino voters to choose GOP candidates. She construes race consciousness as a direct route to civic division.

Unsurprisingly, her instruction to eliminate racial categorization on the Census echoes one of the dominant frames in news coverage of multiracial identity in the 1990s: The state is “forcing” bi- and multiracial people to “choose one race”—that is, forcing people into making a choice that allegedly devalues their individuality and judges them by the color of their skin and not the content of their character.10 In the process, Emery sketches out the second component of the strategy to reframe the party as post-racial: present policy measures aimed to dismantle civil rights legislation as means to promote individual equality. She draws upon the same logic used by anti-affirmative action activist Ward Connerly and his allies: Using racial classifications to identify anyone for any reason is actually racist—and anti-individualistic. Thus, whereas in the past, conservative attacks that counseled colorblindness often depicted people of color as deficient, the newer strategy involves depicting race-aware policies as debilitating and divisive.

Bradley Jones and Roopali Mukherjee have traced the ways neoco...