![]()

1

Goblin Market

London, 1843

Visitors to London in 1843 in search of urban adventure would have done well to alight at the new Fenchurch Street terminus of the London and Blackwall Railway. They would be far from alone, joining a jostling human herd that was disgorged into the streets and alleys close to the Thames. After orientating themselves amid the clamor of the crowds and steeling themselves against the puckering reek of the streets, they would begin pushing through lanes choked with pedestrians and horse-drawn omnibuses, cabs, and carts, stepping around debris and dung scattered underfoot, and moving swiftly past shopkeepers and the quick-fingered who hoped to relieve the unwary of their wallets. The fortunate visitors found a crossing sweeper who, hoping for a small coin as a reward, would clear a path for them through the muck and mud. Otherwise, they required a strong stomach and stout boots as they moved northward toward Spitalfields. The streets became serpentine, cast into shadows by decrepit houses stooped like pious men in prayer and shrouded by a sky ashen with smuts and smoke. The crowds massed anew as they neared their destination. The visitors would soon enter a tattered and multicolored maze of garments, lined at ground level with a parade of shoes and boots and sold at sagging stalls that teetered into Petticoat Lane, Sandys Row, Tripe Yard, Frying Pan Alley, Naked Boy Court, and Moses Square. At first sight the dangling dresses and jackets gave one newcomer “the impression that about an acre of the loveliest of Houndsditch had simultaneously committed suicide.”1 If not diverted by persistent hawkers and swarming street urchins, visitors would do well to follow the shuffling procession of footsore ragmen laden with sacks through the crowds to the alley that led to Phil’s Buildings, to climb the stairs, to pay their halfpenny admission fee to the retired pugilist who acted as gatekeeper, and to enter the vast open-air market beyond. The interior was scarcely less crowded than the street outside. Here was the Clothes Exchange, established in that year of 1843 and already a site of pilgrimage for slum explorers, journalists, and tatterdemalion customers alike in the Dickensian heart of the East End of London.

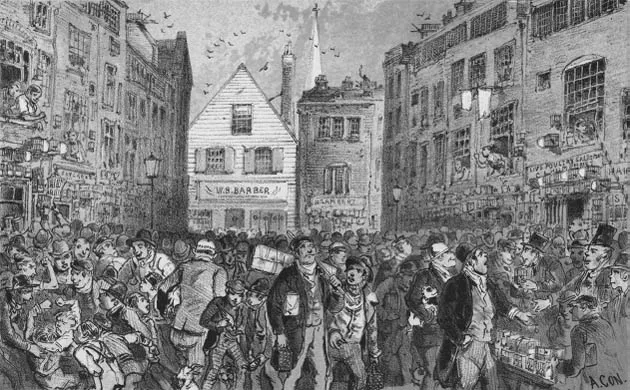

A raucous Sunday morning in the East End. Thousands of customers descended on the area to shop and haggle, making nearby streets all but impassable and producing a fertile field for pickpockets and other petty criminals. (Collection of the author)

Seven thousand square feet in size, the market served as a shabby emporium for rag collectors hoping to sell the clothing they had gathered in London, dealers and retailers buying garments to salvage and resell in Petticoat Lane and the provinces, and bargain hunters shopping to outfit themselves. A pungent fug hung over the Clothes Exchange, bursting forth anew whenever a ragman opened a ripe sack to reveal his daily harvest of castoff clothing. On Sunday, the busiest day at the market, five hundred sellers rented stalls in carefully demarcated spaces to display their wares. A cacophonous throng of customers, estimated at over ten thousand people, descended on the area to shop and haggle, making nearby streets all but impassable and producing a fertile field for pickpockets and other petty criminals. When the light was poor—not an uncommon problem since London’s skies were befouled by factories and coal fires—the mart was lit by oil flares. Our visitors might calm their jangled nerves with a fortifying glass of hot wine bought from a stand at the center of the mart or by something stronger from the Montefiore Arms tavern, which anchored one of its corners. Startled by (and relishing) the exotic scene, few casual visitors were attuned to the sophistication of the mart through which they wandered. The Clothes Exchange pulsed at the center of a circulatory system that sent tattered commodities coursing between the metropolis and distant limbs. And the seemingly chaotic mart was a central node in a Jewish economy that, at its height, stretched from Rag Fair, an impromptu bazaar in Melbourne during the Australian gold rush, to the slave plantations of the American South and the galloping frontier of the American West.2 The Clothes Exchange and the broader ethnic marketplace to which it belonged were far from static and timeless vestiges of a distant past. Instead, they were dynamic, adapting to shifts in the London landscape, pressure from ethnic rivals, developments in the clothing trade, and changes in the Jewish community.

Yet the bargains secured in the Clothes Exchange were centuries in the making, late additions to a long history of Jewish participation in the collection and sale of castoff clothing and the equally long history of Houndsditch as a center of London’s clothing market. The street had been home to old-clothes traders since at least the sixteenth century.3 Although there were several other clothing and shoe markets dotted across London, Houndsditch and Rag Fair—a boisterous open-air market in Rosemary Lane (renamed Royal Mint Street in 1850), closer to the Thames and near Tower Hill—became the epicenter of a Jewish economy during the later decades of the eighteenth century.4 Until the 1840s Rag Fair was the livelier of the two markets, a place where ragmen, dealers, and customers congregated to barter and haggle. In Aldgate, however, the clothing trade initially radiated outward from the dense alleyways and lanes around Cutler Street. Several observers later puzzled over the “very peculiar situation” of the market, noting that the street led only to the warehouses of the East India Company.5 But the site had several advantages for clothing dealers. The alleyway was not a public street, a fact that hindered those who were intent on suppressing trade within its confines.6 Although the East India Company was not pleased by the impromptu daily market that stoppered the street on most afternoons, it had trouble policing the area.7 The site was also interstitched with the trade in textiles. India House, which sat at the far end of Cutler Street, served as a salesroom and auction venue for the East India Company. Although larger merchant houses dominated the purchase of the fine fabrics imported by the company from India, in the eighteenth century Jewish traders came to specialize in the purchase of textiles damaged in transit. At the auctions, prosperous Jewish traders from Amsterdam jostled with their Jewish counterparts of the “lower sort,” some of whom had crossed the English Channel by mail boat to attend the sales.8 Sellers of the crudely sewn shirts and pants dismissively known as “slops” bought cheap cloth to transform into prefabricated apparel for sailors. Jewish buyers were sufficiently important that the East India Company tried not to hold its public auctions on Jewish holidays. Dutch merchants carried cloth back to Amsterdam, which served as a distribution center for goods imported from the British Empire. From this humble seed grew an ethnic economy in the East End.

The Dutch traders who came to Aldgate in search of cheap fabric were, however, only one element in a more complicated and evolving ethnic economy. By the last quarter of the eighteenth century Jewish rag and clothing collectors were a fixture of street life in London. To the eye of the outsider they seemed to wander at random. But there is evidence that collectors walked a regular beat, trudging familiar streets with a pack or basket; proffering flowers, trinkets, crockery, and jewelry in exchange for worn garments; and converging in the afternoon at Rag Fair with their daily harvest of castoff clothing. The collectors were slaves to fashion, lugging to market items cast off by the middle and upper classes (or bartered for other goods by their servants) as outmoded or threadbare. Few of these itinerant collectors were women, although women were involved in the sale of used clothing and were prominent among clothes dealers.9 In the popular imagination, these clothing collectors became visual representatives of Jewish life in the city, subject to disapproving sneers on the streets and opprobrium in the press.10 One journalist jested that “carrying the bag, and crying ‘oghclo,’ seems to be a sort of noviciate or apprenticeship which all Hebrews are subjected to.”11 The clothing and rag collector shared the lowly status of the pawnbroker and the hawker and did not escape the taint of criminality attached to both. At the height of the trade, perhaps one to two thousand Jewish collectors walked the streets of London.12

Although exhausting, the work required no capital, little skill, and only the most basic proficiency in English. For many newcomers it was a temporary or transitional occupation performed until a more promising alternative appeared or until they graduated to dealing in the clothes collected by others. Hawking clothes was more than just physically taxing: among the Jews admitted to London’s lunatic asylums, “clothes dealer” was the most frequently listed occupation.13 To eke out a living, collectors and dealers relied on the value that clothing retained even after being discarded by its original owners. Tailored garments remained beyond the means of much of the population well into the nineteenth century. With tailored clothing out of reach and ready-made clothing relatively expensive, used clothing carried little stigma among the working classes. There was no shortage of purchasers. Castoff clothing was widely worn even after mass-manufactured garments became affordable to wage workers. Paradoxically, the growing number of those who were able to purchase new ready-made clothing ensured that the secondary market was well supplied with discarded garments.14

The clothing trade was part of a fertile economic ecosystem, its roots intertwined with several allied occupations including peddling, pawnbroking, and auctioneering. As historian Beverley Lemire has demonstrated, garments played an essential role in the household economy of the poor, serving as an alternative currency system and a savings mechanism. Even if some of those who bought clothes in Houndsditch were of somewhat higher social rank—clerks, for example, in search of the inexpensive black coats that became the uniform of their caste—the working poor constituted the single largest category of customers for castoff clothing.15 Garments were redeemable for cash or kind, held their value well, and were easy to pawn. (For the same reasons, they remained a popular target for thieves.)16 The poor often assessed new clothing for its pawnability, seeing it as a strategic reserve against hard times. A newly purchased article of clothing might be pawned immediately to cover other expenses, redeemed on the weekend, and then repawned week after week for smaller and smaller sums until its purchaser could afford to own it outright. Most Jewish pawnbrokers in the East End were involved in the “low trade,” pursuing a high-volume and low-margin strategy. Much of their regular business followed a weekly cycle of pawning. Although the rate of interest was limited by law, these small loans were rendered profitable by the fee incurred for each transaction.17 Since clothing and textiles were by far the largest category of items pledged as security, pawnbrokers frequently dabbled in the clothing trade by auctioning or selling forfeited garments.18 In England many pawnbrokers had salesrooms for forfeited items. They also acted as petty bankers for small-scale retailers, selling cheap jewelry to hawkers and peddlers who could resell the items. Pawnbrokers were obliged by law to sell at public auction unredeemed items valued at more than ten shillings, a requirement that connected them with auctioneering.19

The Street Markets

The street markets in Houndsditch and Rosemary Lane specialized in the retail of cheap goods, including haberdashery, and were popular with hawkers and peddlers.20 The London authorities had waged sporadic campaigns against street merchants since at least the early fourteenth century. In January 1700 “several inhabitants” of Rosemary Lane petitioned the county justice of the peace to outlaw “Ragg Fair.” Using arguments that would recur for the next two centuries, they complained of “all manner of wickedness sport and debauchery” and “very great hindrance and disturbance” caused by those who congregated to buy and sell.21 The county’s response established a well-worn pattern, ordering constables to suppress the “unlawful and riotous mootings dayly” for the “buying and selling of old goods wearing apparel” and other articles.22 The constables may have succeeded in the short term, but the traders soon returned. Complainants were forced to rely on private prosecution.23 Several petitions were sent to the Lord Mayor in the 1730s. For example, the Company of Merchant-Taylors implored him to disperse those who ...