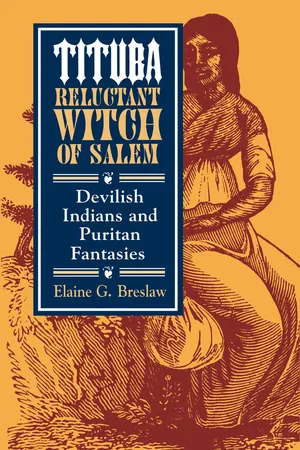

Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem

Devilish Indians and Puritan Fantasies

- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem

Devilish Indians and Puritan Fantasies

About this book

A landmark contribution to women's history that sheds new light on the Salem witch trials and one of its most crucial participants, Tituba of The Crucible

In this important book, Elaine Breslaw claims to have rediscovered Tituba, the elusive, mysterious, and often mythologized Indian woman accused of witchcraft in Salem in 1692 and immortalized in Arthur Miller's The Crucible.

Reconstructing the life of the slave woman at the center of the notorious Salem witch trials, the book follows Tituba from her likely origins in South America to Barbados, forcefully dispelling the commonly-held belief that Tituba was African. The uniquely multicultural nature of life on a seventeenth-century Barbadan sugar plantation—defined by a mixture of English, American Indian, and African ways and folklore—indelibly shaped the young Tituba's world and the mental images she brought with her to Massachusetts.

Breslaw divides Tituba's story into two parts. The first focuses on Tituba's roots in Barbados, the second on her life in the New World. The author emphasizes the inextricably linked worlds of the Caribbean and the North American colonies, illustrating how the Puritan worldview was influenced by its perception of possessed Indians. Breslaw argues that Tituba's confession to practicing witchcraft clearly reveals her savvy and determined efforts to protect herself by actively manipulating Puritan fears. This confession, perceived as evidence of a diabolical conspiracy, was the central agent in the cataclysmic series of events that saw 19 people executed and over 150 imprisoned, including a young girl of 5.

A landmark contribution to women's history and early American history, Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem sheds new light on one of the most painful episodes in American history, through the eyes of its most crucial participant.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Notes

NOTES TO THE INTRODUCTION

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART1 Barbados

- CHAPTERONE Tituba’sRoots:AnArawakfromGuiana

- CHAPTERTWO MyOwnCountry:TitubainBarbados

- CHAPTERTHREE StrangeNewWorld:AnAmericanIndianonaBarbadosPlantation

- PARTIIMassachusetts

- CHAPTERFOUR AnIncompleteTransformation:ATawnyPuritan

- CHAPTERFIVE TheDevilinMassachusetts:Accusations

- CHAPTERSIX TheReluctantWitch:FuelingPuritanFantasies

- CHAPTERSEVEN CreativeAdaptations:ComplaintsandConfessions

- CHAPTEREIGHT DevilishIndiansandWomanlyConversations:Tituba’sCredibility

- EPILOGUE AlteredLives

- APPENDIXA TimetableofAccusationsandConfessions,February-November1692

- APPENDIXB ChronologicalListofConfessions,1692

- APPENDIXC TranscriptsofTituba’sConfessions

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app