![]()

1

Down in Big Blue’s Toxic Plume in Upstate New York

I say, thank God IBM is here to take care of this mess.

—Former Mayor of Endicott

Don’t mitigate me and tell me everything is ok.

—Endicott resident

In September 2008, I was doing fieldwork in Endicott, New York, the site of both IBM’s first manufacturing plant and a contentious U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Superfund1 site consisting of a 300-acre toxic plume of trichloroethylene (or TCE), which is a cancer-causing chlorine-based cleaning solvent heavily used by IBM to manufacture chipboards and other microelectronics. I was sitting down with Tonya, a resident of what is locally referred to as “the plume,” when I first sensed the need to take the concept of mitigation more seriously. Tonya was sitting on the edge of her couch and seemed excited to talk, explaining from the start of the interview that her two boys had moved out two years ago, and that it was nice to have a visitor. Before I asked my first question, she interrupted with, “You mentioned that you wanted to talk about the IBM spill, well just listen.” She pointed across the living room to the western wall of the house. “That’s it,” she says. “I can hear it going all the time. You forget about it, but you also always know it is there.” Tonya was referring to a ventilation system that runs along her chimney stack on the outside wall of the house. It is also known as a vapor mitigation system. Why this humming mitigation system is on Tonya’s house and what it might mean to live in a “mitigated” home in a contaminated neighborhood in a deindustrialized town is a question that, as this book illuminates, opens up a can of worms, for it calls for a perspective on socio-environmental experience that discerns the tangle of social, political, economic, and scientific forces shaping situations and events of technological disaster.

Endicott is in what is known as the “Southern Tier” region of upstate New York and is about three hours northwest of the New York City metropolis. Incorporated in 1906, Endicott is a village in the town of Union and is located in western Broome County along the Susquehanna River. According to the U.S. Census Bureau 2010 Census, Endicott had a population of 13,392, with the majority of residents (86.6%) identifying themselves as white.2 Industry enthusiasm has long been an active pulse of the community, and most especially, at one time at least, Endicott was a proud supporter of International Business Machines Corporation (IBM), which opened its first plant there in 1924. As the “birthplace of IBM,” residents know the local IBM plant played a significant role in the development of the Computer Age. In a Reagan-Bush rally speech on September 12, 1984, Ronald Reagan stood at a podium at Endicott’s high school football field holding a jersey imprinted with his nickname, “The Gipper,” reminding the people of Endicott about their “valley of opportunity,” their valley of prosperity amid an emergent era of American economic policy marked by, among other things, rampant deindustrialization (Bluestone and Harrison 1982). In Reagan’s words:

This valley became home to some of the proudest communities in our nation, towns that had seen firsthand all that free men and women can accomplish … [O]ne group of men and women had a great vision, a vision to bring this valley prosperity it had never before dreamed possible, a vision to launch a revolution that would change the world. … Their leader was Thomas Watson, Sr. He had grown up in a small town called Painted Post, down the road from here, where he learned how to stick with a job until it’s finished. … In 1953 … the company that Watson had renamed IBM began making the first mass-produced commercial computer in history—the IBM 650—less than half a mile from this spot. … When IBM began, the best market researcher predicted that fewer than 1,000 computers would be sold in the entire 20th century. Well, IBM’s first model sold almost twice that number in just 5 years, and now there are IBM plants in Endicott and around the world. And the computer revolution that so many of you helped to start promises to change life on Earth more profoundly than the Industrial Revolution of a century ago. … Already, computers have made possible dazzling medical breakthroughs that will enable us all to live longer, healthier, and fuller lives. Computers are helping to make our basic industries, like steel and autos, more efficient and better able to compete in the world market. And computers manufactured at IBM … guide our space shuttles on their historic missions. You are the people who are making America a rocket of hope, shooting to the stars. … Today, firms in this valley make not only computers but flight simulators, aircraft parts, and a host of other sophisticated products. (Reagan 1984)

Eventually, the high-tech industry’s culture of obsolescence (Slade 2006) caught up with the IBM Endicott plant, resulting in “sophisticated” downsizing and deindustrialization, a topic closely linked to neoliberal political and economic restructuring starting in the late 1970s (Harvey 2007, 2005; Zukin 1991). In 2002, 18 years after Reagan’s speech, IBM’s Endicott plant, which at its peak employed 12,000 workers, was for sale, and residents began to receive invitations in the mail to attend “Public Information Sessions” organized by IBM and state agencies to learn about IBM’s efforts to clean up a groundwater contamination plume (or pollution zone) it was leaving behind. Many of these early information sessions were held at the Union Presbyterian Church in west Endicott, just four blocks from where I lived at the time. I found myself amid this IBM contamination debate as both a resident and a budding anthropologist completing my undergraduate degree at Binghamton University, just six miles to the east. I was as much confused and concerned as a resident as I was interested and curious about the intersections of high-tech production, pollution, and environmental public health politics.

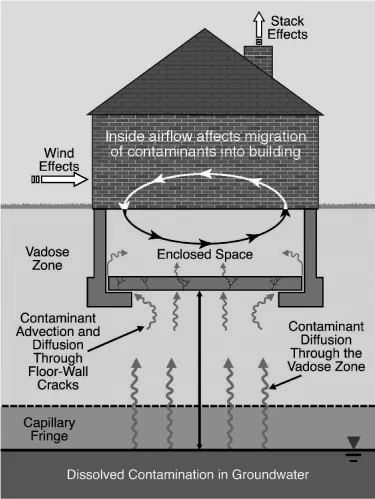

All Endicott residents were invited to these “information sessions.” They were intended to showcase the collaborative effort of IBM and government agencies (e.g., the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, the New York State Department of Health, the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, and later, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) involved in the oversight of the groundwater remediation effort and the emerging problem of toxics vapor intrusion (the process by which volatile organic compounds migrate from groundwater into overlying buildings).

The first time I attended one of these information sessions, I witnessed two women arguing with a representative of the state health department. Keeping to myself, I moved on to the next information table that had a detailed map of the plume area. After spending some time meeting different agency representatives, I grabbed some cookies and juice, secured the numerous “fact sheets” under my arm, and headed home. As I walked out of the building, I ran into the two women who had been arguing with the health official. I introduced myself and explained that I was a resident and student in anthropology at Binghamton University and was interested in learning more about residents’ perspectives on and experiences with the IBM spill. We exchanged numbers, and that interaction planted the anthropological seed in me. It was the starting point of my ethnographic journey, my entry into what forms the focus of this book, which is ultimately how Endicott residents understand and talk about the multiple consequences of the IBM spill; how residents blend contamination and deindustrialization concerns when discussing contemporary Endicott; how residents living in “mitigated” homes above the IBM toxic plume understand and talk about the health risks of toxic exposures and the efficacy of risk mitigation; and what prompted residents to take action and what politics and values did or didn’t inform citizen action.

Guided by these questions, this book explores peoples’ understandings of, negotiations with, and reactions to high-tech industrial pollution in Endicott, New York, the “birthplace” of IBM. It grapples with the various “dynamics of disaster” (Dowty and Allen 2011) provoked by chipboard manufacturing. This text explores how the IBM contamination conflict in Endicott has been shaped by scientific, political, social, and economic factors locally and beyond. In many ways, the struggle of residents living in the IBM-Endicott plume is a response to transformations in the political economy and ecology of the late twentieth century and the early twenty-first century. As a “Rust Belt” community coping with the pains of industrial pollution, deindustrialization, and other rampant neoliberal consequences of an economy based on the ceaseless concentration of finance capital and protection of shareholder interests,3 Endicott has become a high-tech “bust town” (Bluestone and Harrison 1982) struggling with various concerns and uncertainties symbolic of our late industrial times (Fortun 2012). These include layoffs, environmental health risk, property devaluation, a dissipated tax base, stigma, corroding factories, toxic solvents, a general decline in the quality of social and economic life, and the expansion of the “discursive power” of corporate social and ecological responsibility (Rajak 2011). At the same time, among environmental scientists familiar with vapor intrusion, the IBM-Endicott contamination site has become an example-setting site for the large-scale mitigation of TCE vapor intrusion (VI). VI is an emerging environmental public health policy concern at state and federal levels as the connections between groundwater contamination and indoor air impact develop.

This book also presents the first study to examine vapor intrusion risk and mitigation from an ethnographic perspective, and to experiment with a mixture of anthropology, political ecology, and science and technology studies (STS) theory to critically diagnose the social, environmental, and health consequences of high-tech production in the American Rust Belt, a region generally associated with the deindustrialization and decay of the auto and steel industries. I take Latour’s insight seriously: “[t]o ‘study’ never means offering a disinterested gaze and then being led to action according to the principles discovered by the results of the research. Rather, each discipline is at once extending the range of entities at work in the world and actively participating in transforming some of them into faithful and stable intermediaries” (Latour 2005:257).4 The present study confronts the increasing synthesis of political ecology, science and technology studies, environmental justice, and social theories of risk, to augment and transform the anthropology of technological disaster.

A number of anthropologists have engaged the intersection of capitalist production, pollution, and risk (see Balshem 1993; Button 2010; Douglas 1992; Douglas and Wildavsky 1982; Fortun 2001; Fox 1991; Petryna 2002; Tilt 2004, 2006). Different theoretical frameworks have turned these researchers on to different research questions and foci, yet the contentious relationship between industrial toxics and the overwhelming visible and imperceptible consequences and uncertainties of contamination continue to draw the attention of social scientists. Risk and uncertainty invoked by toxic contamination is a sphere of research that has challenged social scientists to rethink and blend theories to better understand the social, political, and economic processes stimulating contamination debates and conditioning residents’ struggles to understand often complex environmental exposures (Scammell et al. 2009). In many ways, this book continues this struggle to understand and uses ethnographic description to contextualize corporate pollution and community response in IBM’s birthplace. Where this book offers something new is the attention it gives to the topic of “mitigation” and local responses to and negotiations with corporate and state efforts “to fix,” to soften the blow or consequences of high-tech industrial pollution. The book critically assesses the efficacy of and social response to toxics mitigation by anchoring the debate in ethnographic description. I don’t claim to be telling the “whole” story, nor do I find that even to be the purpose of anthropology or political ecology. Instead the book adds a new circuit, another angle to the telling of Endicott’s story of microelectronic calamity. Furthermore, it exposes the paradox of IBM as an “environmental” leader in the business world.5 For example, as part of its “corporate responsibility” plan, IBM set as a goal of its “environmental affairs” policy the following: “Be an environmentally responsible neighbor in the communities where we operate, and act promptly and responsibly to correct incidents or conditions that endanger health, safety or the environment. Report them to authorities promptly and inform affected parties as appropriate.”6 This book is a report of another kind. Among other things, it addresses how “responsibility” is received, experienced, made sense of by “affected parties,” and contested by this affected public. It reports instead on how people’s attachments to home, neighborhood, and community have been transformed by irresponsible IBM contamination and deindustrialization, as well as how feelings about dwelling, space, and place are affected by the ecology of senses and understandings provoked by exposure to risks and uncertainties of technological disaster, one of the many persistent themes of late industrialism.

Figure 1.2 Vapor Intrusion Model. Courtesy ITRC.

While many of my interests in and thoughts on the IBM contamination conflict have changed since I first confronted the issue as a resident in 2002, much has stayed the same. First, power relations and epistemic turf wars persist, as is common in “contaminated communities” (Edelstein 2004) where corporate, state, and federal “experts” are set in opposition to a local or “lay” public (Gottlieb 2005; Ottinger 2013; Tarr 1996). In other words, my interests in the contested nature of knowledge and claims to knowing the many dimensions of the contamination and its social, economic, and health consequences endure because this struggle has a particular staying power that will likely inform the future of the debates, regardless of shifting decision-making processes. Even where scientists and citizens have sat down at the table together, there is a persistent “uneasy alchemy” (Allen 2003; Ottinger 2013) that surfaces at public meetings, in news reports, and in the ethnographic narratives explored in this book.

I hold another position that has not waned over time. While grassroots action in Endicott has been “successful” with regard to effectively prodding IBM and government environmental and public health agencies to listen to their concerns and take action, I feel, like many other residents and activists, that no matter what is done to fix the damaged environment and economy of the community, Endicott will never be the place it was when IBM thrived in this region of New York. It is a community of irreversibility in this sense, a chronically de-territorialized and deindustrialized place. There is a clear difference, I was repeatedly told, between Endicott with IBM and Endicott without IBM. Many residents feel they have experienced IBM abandonment, or what might also be called high-tech capital flight (Cowie 1999), as the tax base of Endicott vanished as soon as IBM began to heavily downsize in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s. In this way, I will have succeeded in telling Endicott’s story of toxic struggle only if the reader comes away understanding and still pondering: (1) how and why local idioms of struggle and frustration interconnect deindustrialization, contamination, and risk mitigation experiences; and (2) how and why IBM’s social and environmental responsibility track record is open to social critique.

Ethnographic Fieldwork Overview

This book is based on ethnographic fieldwork that took place during 2002–2003 and 2008–2009. During the 2002–2003 fieldwork, I was a resident of Endicott while completing my undergraduate degree in anthropology at Binghamton University. My honors thesis project (Little 2003) was based on semi-structured ethnographic interviews (N=13) with residents I met at the round of Public Information Sessions that began in 2002, soon after IBM sold its Endicott facility. After securing a grant from the National Science Foundation’s Decision, Risk, and Management Sciences Program, I returned to Endicott in the summer of 2008 to conduct a more in-depth, ethnographic study to better understand the experience of affected residents. What was different this time around was that IBM, under the pressure of the NYSDEC, had installed nearly 500 vapor mitigation systems (VMSs) on homes and businesses in the 300-plus acre plume. This new landscape, what I describe in detail later as the mitigation landscape, added a different twist to the research I had previously done.

In the earlier fieldwork, I was most interested in residents’ understandings of the health-contamination relationship as it related to local drinking water quality and risk. But, with the mass installation of these mitigation systems, I decided it was appropriate to explore local environmental health risk perception vis-à-vis the mitigation effort, to explore community understandings of vapor intrusion and the degree to which residents living in the “mitigated” plume area trust IBM and the responding government agencies. What follows is a description of the field methods used to investigate these research interests during the 2008–2009 fieldwork.

I returned to Endicott in June 2008, and my goal was to use a combination of qualitative and quantitative ethnographic methods to help tell the story of local struggle and negotiation in the mitigation phases of the IBM spill (Little 2010). I conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with local residents (n=53), including residents living within the defined plume area that encompasses more than 300 acres in the central downtown area of Endicott, and those living outside the plume boundary. These interviews explored how the IBM contamination issue and the mitigation effort are subjectively understood by Endicott residents, local activists, public officials, and regulators and scientists involved in vapor intrusion research in Endicott and nationwide. All interviews were tape recorded with permission and an informed consent document was signed before all interviews. I also did many follow-up interviews by phone and corresponded with activists via email communication. Stratified snowball sampling was used to recruit research participants for this phase of the project (Bernard 2006). My sample was “stratified” or targeted in the sense that I defined “plume” residents as those that lived in the plume, and would get contacts from plume residents about other plume residents. For the activists I interviewed, I targeted residents and community advocates who had direct connections with advocacy groups (e.g., Western Broome Environmental Stakeholders Coalition and the New York State Vapor Intrusion Alliance, and Alliance@IBM) working on the IBM-Endicott issues and who could connect me with others engaged in the network of activists working on these issues.

Another goal of my ethnographic research was to develop a quantitative survey questionnaire that could provide another pathway of characterizing (or visualizing) the experience and perspective of “mitigated” residents living in the plume with vapor mitigation systems. I developed the plume survey instrument in collaboration with memb...