![]()

1

A French Way of Warfare

Thus the day passed away: the French stood immovable, Kellermann having taken also a more advantageous position. Our people were withdrawn out of the fire, and it was exactly as if nothing had taken place. The greatest consternation was diffused among the army. That very morning, they had thought of nothing short of spitting the whole of the French and devouring them; nay I myself had been tempted to take part in this dangerous expedition from the unbounded confidence I felt in such an army and in the Duke of Brunswick; but now everyone went about alone, nobody looked at his neighbor, or if it did happen, it was to curse or to swear. Just as night was coming on, we had accidentally formed ourselves into a circle, in the middle of which the usual fire even could not be kindled: most of them were silent, some spoke, and in fact the power of reflection and judgment was awanting to all. At last I was called upon to say what I thought of it; for I had been in the habit of enlivening and amusing the troop with short sayings. This time I said: “From this place and from this day forth commences a new era in the world’s history, and you can all say that you were present at its birth.”

—Goethe1

It was only right that Goethe, one of the most brilliant minds of the eighteenth century, declared the French Revolution a watershed moment in European history on the battlefield that saved the new republic from international intervention. The French Revolution unleashed new ideas that fundamentally altered French culture, while at the same time realizing Enlightenment military reforms deemed anathema by the armies of the ancien régime. The result was a way of warfare that matched the unique capabilities of the citizen-soldier with a new system of tactics. This new system disregarded the limitations of eighteenth-century warfare and proved superior to the system of Frederick the Great. This intellectual framework, called the French combat method, informed military affairs far beyond the borders of France, becoming a transnational cultural influence. The French combat method transformed American warfare through the use of French regulations and the acceptance of French culture in American society. Therefore, an understanding of the American way of warfare is incomplete without an understanding of the fundamental elements of the French combat method.

The Conceptual Framework of Eighteenth-Century Warfare

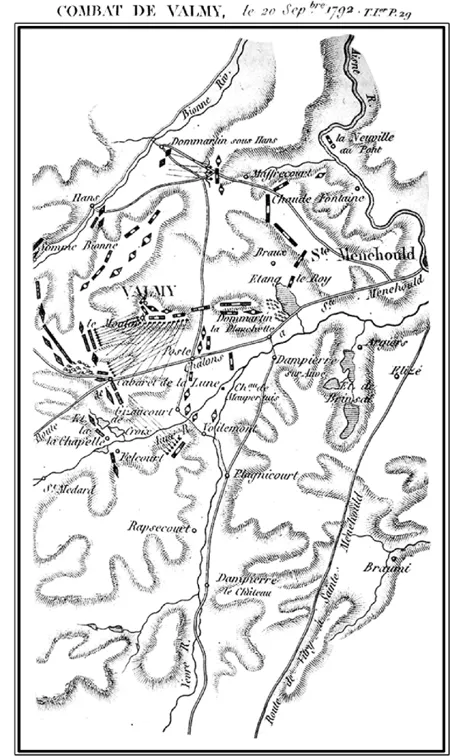

The Battle of Valmy: 20 September 1792

Goethe joined the 42,000-man Prussian army commanded by Charles William Ferdinand Duke of Brunswick in late July 1792. While Kaiser Frederick William of Prussia wanted to ride straight to Paris and restore the Bourbon monarchy in a single campaign, Brunswick envisioned a more methodical approach. He wanted to seize the French frontier fortresses, establish depots, defeat French relieving armies, and prepare for a more decisive campaign the following year. This was consistent with his reputation, as much of the ruling elite considered Brunswick the preeminent soldier of Europe, largely for his bloodless, methodical, and victorious 1787 Holland campaign.2 Brunswick quickly seized the fortress of Longwy on 23 August 1792 and established his base of operations for the invasion of France. Through a series of skirmishes, he pushed aside several French armies and advanced toward the fortress of Verdun.3 It was not until the fall Verdun, on 2 September, the last frontier fortification on the road to Paris, that Charles François Dumouriez took command of all of the French armies on the frontier.4 When the Prussian army left Verdun for Paris, Dumouriez concentrated his forces across Brunswick’s line of communications back to Prussia. This caused Brunswick to turn around and attack back to Verdun. While marching east, the Prussian army encountered the French at the village of Valmy.

The Prussians marched toward a part of Dumouriez’s army under the command of François-Christophe Kellermann that consisted of a mix of volunteer battalions, old royal infantry battalions, and several batteries of artillery. Kellermann deployed his 36,000 men at Valmy on a series of small hills that formed a semicircle west of the town to cut the road to Verdun, while Dumouriez maintained an additional 25,000 men in reserve to the east.5 When Prussian scouts found the French at Valmy, Brunswick decided to attack, expecting them to disintegrate like those French armies on the frontier. While the Prussian infantry formed into its order of battle, the Prussian artillery fired on the French position, beginning the famous cannonade of Valmy. For hours the Prussian and French artillery fired thousands of rounds at each other, which caused few casualties and failed to break the French lines.6 Seeking to panic the French, the Prussians began their attack up the slopes of Mount Yron, but for the first time since the beginning of the campaign, the French did not run. Without the advantage of a panicked enemy, Brunswick stopped the attack after only 200 meters. Several minutes later, Prussian cannon balls struck several French powder caissons, causing a loud explosion and the panic of two French regiments. Brunswick ordered the resumption of the attack, but before his orders could be relayed to the infantry, the French line rapidly reformed, and the French artillery resumed its cannonade.7 The Prussians remained on the field for another two hours before calling off the attack and retiring in good order.8 With the road to Verdun under French control, the Prussian army began to disperse shortly after leaving Valmy. Discipline in the retreating army broke down rapidly, and Brunswick abandoned Verdun and Longwy because he did not have enough troops or supplies to garrison them.9

Figure 1.1. The Battle of Valmy (Reprinted from Charles Théodore Beauvais de Préau, ed., Victoires, conquêtes, désastres, revers et guerres civiles des français, de 1792 à 1815, vol. 1 [Paris: C. L. F. Panckoucke, 1818–21], facing p. 28)

After an inauspicious beginning, French armies controlled the frontier and saved the Republic by the end of 1792. The battle of Valmy presents a perfect opportunity to understand the eighteenth-century European intellectual framework of the battlefield. There was no attempt to maneuver the French out of their position or to press the attack, two of the central themes of eighteenth-century warfare. Kellermann’s army had a number of volunteer formations of questionable value, and if any of these formations panicked before a deliberate Prussian attack, the French line might have collapsed. The French and Prussian armies at Valmy were almost numerically equal. The Prussians had a good chance of routing the majority of Kellermann’s army and then outnumbering Dumouriez’s reserve. Knowing the result of the campaign, the possibility of destroying at least a part of Dumouriez’s army was better than losing all of the Prussian territorial gains and Brunswick’s army. If there were so many logical reasons for Brunswick to continue his attack at Valmy, why did he decide to retreat, leaving the French army intact and the revolution secure? Why did Brunswick consider his generalship of the campaign, if not successful, then at least prudent?10 From his point of view, Brunswick made wise decisions to husband the strength of his army to fight another day on a battlefield that offered more advantages. The answer lies with Brunswick’s intellectual framework of the battlefield and, by extension, the eighteenth-century way of warfare.

The Paradigm of Ancien Régime Linear Warfare

The political and military environment of eighteenth-century Europe produced a unique way of warfare. The capabilities and constraints on armies and battles, both military and political, led to an intellectual framework of the battlefield for the age of “linear warfare.” While it is not within the purview of this work to make a detailed analysis of this framework, a brief description of its major ideas will help understand Brunswick’s decisions at Valmy. With the rise of ever powerful centralized states on the model of Louis XIV, European warfare became the purview of professional standing armies.11 These armies had specialized units of heavy line and light infantry whose maneuvers on the battlefield maximized the impact of their muskets and bayonets on the enemy.12 The increased dependence on gunpowder created logistical requirements that led nations to maintain large depots of military stores along their frontiers. These fortified depots made lines of communication vitally important to an army on campaign, as armies could not sustain themselves for long in enemy territory without logistical support.13 The creation of the depot system was a result of the experiences of the Thirty Years’ War and designed to avoid the political instability caused by extensive foraging. This meant that cutting an enemy army’s lines of communication was almost certain to force its retreat. Combined with the expense and investment represented by standing armies, this created a maneuver-centric way of warfare.

These themes dominated the intellectual framework of the day through a combination of memoirs, theoretical pamphlets, and major works on the art of war. Authors encouraged commanders to fight battles only when they gained an advantage over the enemy through position, terrain, or maneuver.14 Some maneuvers were so powerful as to make the enemy retreat without firing a single shot. Marshal Maurice de Saxe identified this as the hallmark of a superior general when he wrote, “I do not favor pitched battles, especially at the beginning of a war, and I am convinced that a skillful general could make war all his life without being forced into one.”15 Victory through maneuver also had the added benefit of reducing the cost of battles by saving lives. This concern for the lives of soldiers, many of whom came from the lowest levels of society, was a desire to reduce the costs of war, as the expense of armies due to their equipment and years of training drained royal coffers.16 However, effective maneuver produced an advantage in the event of a battle, and there was no shortage of battle during the age of “limited” war.

Frederick the Great was a great proponent of battles and taught his generals,

If you wish to be loved by your soldiers, husband their blood and do not lead them to slaughter. They can be spared by shortening the battle by means that I shall indicate, by the skill with which you choose your points of attack in the weakest localities, in not breaking your head against impracticable things which are ridiculous to attempt, in not fatiguing the soldier uselessly, and in sparing him in sieges and in battles. When you seem to be most prodigal of the soldier’s blood, you spare it, however, by supporting your attacks well and by pushing them with the greatest of vigor to deprive time of the means of augmenting your losses.17

In this paragraph, Frederick refers to two different components of his intellectual framework of the battlefield. The first refers to the advantage gained through maneuver and the utilization of terrain. The second describes the organization and tactics required for victory on the battlefield. In order to press an attack with vigor, an army had to integrate its reserves into the main line of battle to ensure that all possible firepower affected the enemy’s formations.18 The commanding general dictated the entire order of battle prior to the combat, deployed his whole force into a single formation, and launched his infantry against the enemy.19 When the two formations collided, the better trained and drilled units produced a higher volume of fire by continuing to operate their muskets amid the carnage created by the short-range volley fire of smoothbore muskets.20 The harsh discipline required to create effective infantry on the linear battlefield became a requirement for victory and a limiting factor of eighteenth-century warfare. To maximize effectiveness, armies contained different types of infantry. Thus, the heavy line infantry trained only to fight as line infantry, and light infantry only as light infantry. Once the commander determined his order of battle and issued his orders, victory came down to a single blow by the entire army, even if this blow took hours to land.21 If it failed to drive the enemy from the field or shatter its formation where it stood, then victory remained unattainable.

With this basic understanding of the intellectual framework of the battlefield for eighteenth-century European warfare, we can provide a much more complete analysis of Brunswick’s decisions on the battlefield of Valmy. Brunswick represented the epitome of the eighteenth-century commander and conducted his campaign in accordance with the fundamental elements of his intellectual framework. By concentrating the French armies across the Prussian lines of communication, Dumouriez constrained Brunswick’s options for maneuver. Any additional maneuver required Brunswick to march farther away from his depots. Severing his lines of communication represented a tremendous risk to both the Prussian army and its ability to remain an effective fighting force. This left an attack as Brunswick’s only reasonable option. However, attacking Kellermann’s position gave the French the advantage of terrain. As Brunswick’s paradigm supported attacks only from a position of advantage, a French panic represented his only hope of creating an opportunity for a victorious infantry attack. When the enemy remained in its formations after an advance of 200 meters, he had no choice but to withdraw from the battle and begin what became a disastrous retreat to the frontier. Brunswick had no choice because his intellectual framework prohibited a frontal attack against a disciplined enemy on defensible terrain, regardless of the chances for victory. Such a victory could cause irreparable damage to the Prussian army and, even if it were successful, would make that army incapable of further offensive operations. German military historian Hans Delbrück exonerated Brunswick for his decision at Valmy, stating that the decision was consistent with those made by Frederick the Great.22

Ironically, Kellermann also fought according to the eighteenth-century intellectual framework of the battlefield. He chose the position at Valmy both to cut Brunswick’s lines of communication and because the hills surrounding the village provided an advantage over attacks from three sides. It was the royal regiments that held his line together under the cannonade and reformed so rapidly after the caissons exploded. It was also the royal artillery batteries that responded to the Prussian guns during the cannonade. In fact, the only new element in Kellermann’s generalship that day was his resort to revolutionary patriotism when inspiring his troops to hold the line before the Prussian advance. However, this patriotism was only one of many forces already at work within the French armies that in short order fundamentally changed French warfare.

The New French Way of Warfare

From 1791 through 1794, the armies of the French Republic developed a new way of warfare that combined the ideas of the prerevolutionary period with the new capabilities brought on by the French Revolution. The Prussian General Gerhard von Scharnhorst, who spent years fighting the armies of the French Revolution, believed that the French army, “compelled by the situation in which they found themselves and aided by their national genius, had developed a practical system of tactics that permitted them to fight over open or broken ground, in open or close order, but this without their being aware of their system.”23 Scharnhorst witnessed new French tactics that were more flexible, responsive, and agile during the wars of the Revolution. This system of tactics w...