![]()

[1]

Introduction

THE MOST STRIKING characteristic of whites’ consciousness of whiteness is that most of the time we don’t have any. I call this the transparency phenomenon: the tendency of whites not to think about whiteness. Instead, white people externalize race. For most whites, most of the time, to think or speak about race is to think or speak about people of color, or perhaps, at times, to reflect on oneself (or other whites) in relation to people of color. But we tend not to think of ourselves or our racial cohort as racially distinctive. Whites’ “consciousness” of whiteness is predominantly unconsciousness of whiteness. We perceive and interact with other whites as individuals who have no significant racial characteristics. In the same vein, the white person is unlikely to see or describe himself in racial terms, perhaps in part because his white peers do not regard him as racially distinctive. Whiteness is a transparent quality when whites interact with whites in the absence of people of color. Whiteness attains opacity, becomes apparent to the white mind, only in relation to, and in contrast with, the “color” of nonwhites.

This is not to say that white people are oblivious to the race of other whites.1 Race is undeniably a powerful determinant of social status and so is always noticed, in a way that eye color, for example, may not be. However, whites’ social dominance allows us to relegate our own racial specificity to the realm of the subconscious. Whiteness is the racial norm. In this culture the black person, not the white, is the one who is different.2 The black, not the white, is racially distinctive. Once an individual is identified as white, his distinctively racial characteristics need no longer be conceptualized in racial terms; he becomes effectively raceless in the eyes of other whites. Whiteness is always a salient personal characteristic, but once identified, it fades almost instantaneously from white consciousness into transparency.

The best “evidence” for the pervasiveness of the transparency phenomenon will be the white reader’s own experience: Critically assessing our habitual ways of thinking about ourselves and about other white people should bring transparency into full view.3 The questions that follow may provide some direction for the reader’s reflections. In what situations do you describe yourself as white? Would you be likely to include “white” on a list of three adjectives that describe you?4 Do you think about your race as a factor in the way other whites treat you? For example, think about the last time some white clerk or salesperson treated you deferentially, or the last time the first taxi to come along stopped for you. Did you think, “That wouldn’t have happened if I weren’t white”? Are you conscious of yourself as white when you find yourself in a room occupied only by white people? What if there are people of color present? What if the room is mostly nonwhite?

Do you attribute your successes or failures in life to your whiteness? Do you reflect on the ways your educational and occupational opportunities have been enhanced by your whiteness? What about the life courses of others? In your experience, at the time of Justice Souter’s nomination, how much attention did his race receive in conversations among whites about his abilities and prospects for confirmation? Did you or your white acquaintances speculate on the ways his whiteness might have contributed to his success, how his race may have affected his character and personality, or how his whiteness might predispose him to a racially skewed perspective on legal issues?

If your lover or spouse is white, how frequently do you reflect on that fact? Do you think of your white friends as your white friends, other than in contrast with your friends who are not white? Do you try to understand the ways your shared whiteness affects the interactions between yourself and your white partner, friends, and acquaintances? For example, perhaps you have become aware of the absence of people of color on some occasion. Did you move beyond that moment of recognition to consider how the group’s uniform whiteness affected its interactions, agenda, process, or decisions? Do you inquire about the ways white persons you know have dealt with the fact, and privilege, of their whiteness?

Imagine that I am describing to you a third individual who is not known to you. I say, for example, “She’s good looking, but rather quiet,” or “He’s tall, dark, and handsome.” If I do not specify the race of the person so described, is it not culturally appropriate, and expected, for you to assume she or he is white?5

* * *

Transparency casts doubt on the concept of race-neutral decisionmaking. The criteria upon which white decisionmakers rely when making a decision may be as vulnerable to the transparency phenomenon as is the race of white people itself. At a minimum, transparency counsels that we not accept seemingly neutral criteria of decision at face value. Most whites live and work in settings that are wholly or predominantly white. Thus whites rely on primarily white referents in formulating the norms and expectations that become the criteria used by white decisionmakers. Given whites’ tendency to be unaware of whiteness, it’s likely that white decisionmakers mistakenly identify as race-neutral personal characteristics, traits, and behaviors that are in fact closely associated with whiteness. The ways in which transparency might infect white decisionmaking are many and varied. Consider the following story.

A predominantly white Nominating Committee is considering the candidacy of Delores, a black woman, for a seat on the majority white Board of Directors of a national public interest organization. Delores is the sole proprietor of a small business that supplies technical computer services to other businesses. She founded the company eleven years ago; it now grosses over a million dollars annually and employs seven people in addition to the owner. Delores’ resume indicates that she dropped out of high school at sixteen. She later obtained a G.E.D. but did not attend college. She was able to open her business in part because of a state program designed to encourage the formation of minority business enterprises.

Delores’ resume also reveals many years of participation at the local and state levels in a variety of civic and public interest organizations, including two that focus on issues that are of central concern for the national organization that is now considering her. In fact, she came to the Committee’s attention because she is considered a leader on those issues in her state.

During Delores’ interview with the Nominating Committee, several white members question her closely about the operation of her business. They seek detailed financial information that she becomes increasingly reluctant to provide. Finally, the questioning turns to her educational background.“Why,” one white committee member inquires, “didn’t you go to college later, when you were financially able to do so?”“Will you be comfortable on a Board where everyone else has at least a college degree?” another asks. Delores, perhaps somewhat defensively, responds that she is perfectly able to hold her own with college graduates; she deals with them every day in her line of work. In any event, she says, she does not see that her past educational history is as relevant to the position for which she is being considered as is her present ability to analyze the issues confronting the national organization. Why don’t they ask her hypothetical policy questions of the sort the Board regularly addresses if they want to see what she can do?

The interview concludes on a tense note. After some deliberation, the Committee forwards Delores’ name to the full Board, but with strong reservations. “We found her to be quite hostile,” the Committee reports. “She has a solid history of working on our issue, but she might be a disruptive presence at Board meetings.”

At least three elements of the decisionmaking process in this story may have been influenced by the transparency phenomenon. We can examine the first of these only if we assume that the white committee members would question every Board candidate who operates a small business in exactly the same manner they queried Delores. (If they have subjected her to more intense inquiry, perhaps reflecting unconscious skepticism concerning a black woman’s ability to establish and manage a successful, highly technical small business, the situation ought to be analyzed as an example of stereotyping rather than transparency).6 Assuming no such racial (or, for that matter, gender) stereotyping was at work, so that the questioning was in fact uniform for black and white candidates, it still does not follow that those candidates would interpret the inquiries in the same way. It’s predictable that a black interviewee might take exception to such a line of questioning because of the common white image of blacks as not very intelligent; given that the candidate has no prior knowledge of her white interviewers, she might reasonably wonder whether the questions arise from that image, even if they in fact do not. A white candidate, on the other hand, would come to the interview without any history of being viewed in that way, and so should be expected to respond to the line of questioning with greater equanimity. Transparency—here, the unconscious assumption that all interviewees will, or should, respond to a given line of questioning the way a white candidate (or the interviewers themselves) would respond—may account for the white questioners’ inability to anticipate the more subtle implications their queries might have for the nonwhite interviewee.

Second, the white committee members may be imposing white educational norms as well. Anyone smart enough to attend college surely would do so, they might assume. However, whites attend college at a higher rate than blacks. The committee members’ assumption takes into account neither the realities of the inner city schools this woman attended, nor the personal and cultural influences that caused her to decide to drop out of high school, nor the ways the cost-benefit analysis of a college education might appear different to a black person than to a white person. Delores’ business success suggests that she made a rational and effective decision to develop her business rather than divide her energies between the business and school. Transparency may blind the white committee members to the whiteness of the educational norms they and their organization appear to take for granted.

The most troubling and perhaps least obviously race-specific aspect of the story is the ultimate assessment of Delores as “hostile.” This seemingly neutral adjective is in fact race-specific in this context insofar as it rests on norms and expectations that are themselves race-specific. To characterize this candidate’s responses as hostile is to judge them inappropriate. Such a judgment presupposes an unstated norm of appropriate behavior in that setting, one that reflects white experience, priorities, and life strategies. The committee members’ expectations did not take into account some of the realities of black life in the United States that form part of the context in which the black candidate operates. The transparency of white experience and the norms that flow from it permitted the Nominating Committee to transmute the appropriate responses of a black candidate into a seemingly neutral assessment of “hostility.”

* * *

Transparently white decisionmaking is one form of institutional racism, defined as any institutional practice that systematically creates or perpetuates racial advantage or disadvantage. This conception of racism differs from ones that revolve around notions of individual prejudice and hostility, and in fact carries no requirement that the individuals who created the institution in question or who participate in it harbor any conscious dislike of, or animus toward, nonwhites. It is the thesis of this book that even seemingly “benign” participation in racially unjust institutions fully implicates individuals in the maintenance of white supremacy. Those who wish to claim a nonracist white identity must find active ways of dismantling existing systems of racial privilege.

One available strategy is to challenge insistently every example of transparency in white decisionmaking. We can work to reveal the unacknowledged whiteness of facially neutral criteria of decision, and we can adopt strategies that counteract the influence of unrecognized white norms. These approaches permit white decisionmakers to incorporate pluraiist 7 means of achieving our otherwise nonracist aims, and thus to contribute to the racial redistribution of social power.

Law might assist in this endeavor, but at present race discrimination law is unresponsive to the transparency phenomenon. Existing laws embody too narrow a concept of race discrimination to include nonobvious forms of institutional racism.8 Consequently, race discrimination law does not currently provide any legal remedies for discrimination that takes the form of transparently white decisionmaking. In effect, today’s race discrimination law is itself a form of institutional racism: By failing to address transparency, it contributes to the maintenance of a racially unjust status quo.

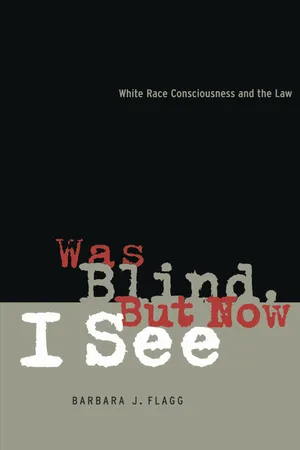

This book explores the contribution a transformed race discrimination law might make to rectifying the effects of the transparency phenomenon. I proceed on the premise that recognizing, analyzing, and devising responses to transparently white decisionmaking in everyday settings and in law is a synergistic enterprise. Our understanding of the ways transparency plays itself out in life can inform our critique of antidiscrimination law, and, conversely, the project of assessing the theoretical foundation, symbolic import, and practical effects of antidiscrimination law can serve as a context in which to reexamine who we, as white people, are and want to be. Accordingly, this book critically analyzes two central examples of race discrimination law with the ultimate objective of exploring the implications of transparency-conscious doctrinal reform, reciprocally, for law and for white race consciousness itself.

The antidiscrimination provisions under examination here are the Equal Protection Clause of the United States Constitution, which requires government to extend “the equal protection of the laws” without regard to race, and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which proscribes race discrimination in employment. The specific focus of the analysis will be the Equal Protection and Title VII rules governing the use of seemingly neutral criteria of decision that, even when applied evenhandedly, have racially skewed effects; these rules are singled out because transparency is a phenomenon that manifests itself in facially neutral forms. In Equal Protection jurisprudence there is a requirement of discriminatory intent: a judicially created rule that government bears a burden of justification with regard to a practice carrying racially disparate effects only when it can be shown that the practice was adopted with discriminatory intent. As is perhaps obvious, the requirement of discriminatory intent operates as an absolute barrier to recognition of unconscious discrimination, and so fails to provide any foothold for attacking the transparency phenomenon. One might wonder, then, whether jettisoning the intent requirement would produce more satisfactory results. Title VII provides an example of that approach, as it places a requirement of justification upon an employer solely upon proof of disparate effects. However, careful examination reveals that Title VII too falls short with respect to transparently white decisionmaking.

Chapter 2 provides a foundation for the analysis of existing Equal Protection and Title VII rules, and for the formulation of more satisfactory legal doctrines, by sketching the general contours of the universe of racism’s various manifestations and locating transparently white decisionmaking on that conceptual map. It then surveys possible antiracist strategies, again with particular emphasis on antiracist responses to transparently white decisionmaking. This chapter explains how transparently white decisionmaking might be countered by adopting a thoroughgoing skepticism regarding the neutrality of seemingly race-neutral decision criteria. Such skepticism amounts to a presumption against the race neutrality of apparently neutral criteria of decision, and thus provides an opening for the formulation of criteria more capable of effecting distributive racial justice. The skeptical stance provides a benchmark for the critique of antidiscrimination law.

Chapter 3 scrutinizes the constitutional requirement of discriminatory intent and concludes that it does not provide any point of contact for grappling with the transparency phenomenon in decisionmaking. It then proposes an alternative approach to disparate effects cases that would incorporate the thoroughgoing skepticism just described: Race discrimination law ought to incorporate a presumption that ostensibly race-neutral criteria of decision are in fact race-specific, and thus ought to provide a legal remedy for transparently white decisionmaking, in the absence of a persuasive justification for the challenged practice.

Clearly, the concepts of transparently white decisionmaking, institutional racism, and deliberate skepticism that inform this analysis are not universally shared in American culture. Constitutional interpretation always is a complicated subject, and it is especially so with respect to contested social values. Many legal commentators hold that it is improper for judges to superimpose their own vision of desirable social policy on the constitutional text; accordingly, in their view, constitutional interpretation is performed best when it is an exercise in judicial restraint. This contention is the subject of chapter 4.

Chapter 5 explores the legal regime of Title VII, in which seemingly neutral criteria of decision that produce racially disparate effects are subject to justification even without proof of discriminatory intent, and concludes that even under this approach there are substantial barriers to recognition of, and legal redress for, transparently white decisionmaking. This chapter sets forth two alternative proposals, either of which promises to be more effective in combatting transparency than the current rules. These proposals in turn give rise to another set of concerns: Even if it is desirable for individuals to acknowledge transparency by adopting a skeptical stance regarding their own decisionmaking (and for government voluntarily to do the same), it may be inappropriate for government to require individual employers to do so. These concerns will be addressed in the course of chapter 6 ’s discussion of the foundation and scope of Title VII.

The book concludes with a discussion, in chapter 7, of several jurisprudential and larger implications of the transparency-conscious proposals set forth in chapters ...