![]()

1

Introductory Images

MOST AMERICANS DISLIKE lawyers, but we generally either hold our tongues or express our disdain quietly. In particular, we tend to speak only good of the dead, even of dead lawyers.

This was not to be the fate of William Moses Kunstler. When Kunstler died on September 4, 1995, controversy followed him to the grave. His many obituaries spoke of hatred as much as praise. One journal entitled its obituary “The Pariah’s Farewell,” and a second reminded its readers that Vanity Fair had branded Kunstler “the most hated lawyer in America.” Another obituary recalled that the New York Times had labeled Kunstler both the “most hated and most loved lawyer in America.” These same conclusions arrived from overseas. For the London Times, Kunstler was “the most celebrated and detested lawyer in America,” and the Economist observed that Kunstler’s “critics came in all colours of the political rainbow . . . and he missed no chance to infuriate them with glib throw-away lines honed for maximum offense.”

Controversy followed Kunstler even after the obituaries. Kunstler was not conventionally religious, and there was no funeral service. However, friends held two memorial celebrations, one in Chicago and another in New York. The Cathedral of St. John the Divine hosted the New York celebration on November 19, 1995. Over three thousand clients, colleagues, friends, family, and well-wishers attended. Members of the Jewish Defense Organization also showed up to protest behind police barricades. Their leader shouted, “William Kunstler is where he belongs!” The group argued that Kunstler had betrayed his Jewish roots by representing Arabs, such as Sheikh Omar AbdelRahman and others charged with bombing the World Trade Center, and El Sayyid Nosair, the Arabic youth charged with murdering Rabbi Meir Kahane.

Kunstler’s delight in representing society’s outcasts and pariahs, in seeking out criminal defendants most loathed by mainstream, conventional America, generated this controversy. If he agreed with their politics, Kunstler embraced these individuals, usually representing them free of charge and sometimes achieving acquittals in hopeless cases. For his often penniless clients, Kunstler represented a lifeline of hope for the possibility of a life other than execution or lifetime incarceration. His harshest critics saw him simply as a publicity seeker, forever hogging the limelight. To his more thoughtful detractors, such as Alan Dershowitz, a civil rights lawyer and Harvard law professor, “Bill was a radical revolutionary lawyer. He stretched the line for where lawyer ends and revolutionary begins. . . . his support of free speech was because it was a tactic of the left . . . his views were cause oriented.” Immediately following Kunstler’s death, Dershowitz said, “I have great compassion for God now, because I think Bill is going to start filing lawsuits as soon as he gets to heaven.” For his friends on the Left, Kunstler “identified with those struggling against racism and capitalism.” He was a “friend of the people . . . and a consummate people’s lawyer, who both knew the legal system and treated it with the contempt it richly deserves.”

After his death, both friends and foes agreed on one thing: Kunstler had been a happy man who enjoyed every minute of his life exuberantly and fully. He loved his work and “plunged” (a word used repeatedly by colleagues, secretaries, and friends) into each of his cases with enthusiasm. He fought doggedly once he had entered a case. If he lost at trial, he looked forward to the appeal. If he lost the appeal, then he looked forward to habeas petitions or other post-appellate remedies.

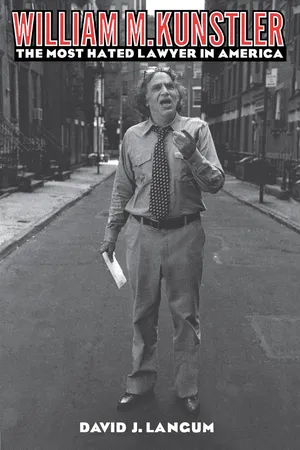

With his long, unruly hair, glasses pushed back onto his forehead, rumpled suit, and deep, resonant voice extravagantly condemning authority and system, yet exuding personal charm, Kunstler seemed like an actor playing a part. Even in private, he acted as though he were on stage, flamboyantly instructing or entertaining, sometimes dissembling. In public, through thousands of interviews and “bites” for radio and television, Kunstler’s own persona largely formed our collective image of the role of radical lawyer, what one looked and sounded like. Indeed, toward the end of his life Kunstler embarked on a minor acting career. In some of his roles he simply played himself, as he did in an October 1994 episode of the NBC police show Law & Order.

Nevertheless, the picture of Kunstler as hardworking, enthusiastic, radical gadfly is far from complete. Many of his cases were not merely matters involving political opponents of American society and government, nor were they simply important cases. Instead, and especially in the 1960s and 1970s, many of Kunstler’s cases defined and encapsulated the turmoil through which America was passing. Then too, William Kunstler as a man was more nuanced and complicated than the term “radical lawyer” suggests. To listen merely to his oratorical pronouncements would suggest that Kunstler had a Manichaean view of the world, that the people, the movement, and racial minorities were clearly identifiable as “good” on one hand, and the racists, capitalists, and authoritarians as “bad” on the other. But that is far too simplistic a view of a man who wrote twelve books of prose and poetry, most having little to do with politics, and was himself profoundly torn between the values and lifestyle he inherited from the middle-class professional family into which he was born and the youthful radicals he often represented.

Kunstler was hated because of the clients he represented and the relish with which he sought out pariahs and outcasts. He knew he was “disliked, even despised, by those who hate my clients,” whom he characterized as “outcasts, individuals who are hated for their skin color or religion or political beliefs, people who fight the government. These are exactly the kind of clients I want . . . the damned, those whom society wants to destroy.”

Kunstler did not begin his legal career with this attitude. After he had practiced conventional civil law for a dozen or so years, in 1961 the American Civil Liberties Union asked Kunstler to act as an observer in Mississippi, to protect the rights of several hundred Freedom Riders. His experience in the South began his transformation. After he witnessed the beatings inflicted on blacks by white southerners and the encouragement of this oppression of blacks by the southern legal system, he joined the civil rights struggle. “No longer satisfied practicing conventional law and talking liberal politics,” as he later wrote, Kunstler began traveling hectically throughout the South, playing a major role in enlisting the federal judicial system to support the civil rights movement. In the early to mid-1960s he served as a private attorney to Martin Luther King, and also to such Black Power advocates as H. Rap Brown, who startled white observers by his declaration that violence “is as American as cherry pie,” and Stokely Carmichael, who advised black audiences in 1966 and 1967 that “the only way these honkies and honky lovers can understand is when they’re met by resistance. . . . If their armed aggression continues, we will resist by any means necessary.”

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Kunstler’s attention shifted to the struggle against the Vietnam War. He represented Fathers Daniel and Philip Berrigan, the Roman Catholic priests who sprayed napalm on draft files in Catonsville, Maryland, and set them afire to protest the American use of napalm against the Vietnamese people. He represented the surviving Kent State students, charged with riot by the state of Ohio, which at the same time refused to prosecute the National Guardsmen who shot and killed their fellow students. Kunstler’s single most important case arose out of the antiwar movement when he represented the Chicago Seven before the cantankerous federal judge Julius Hoffman. The Nixon administration prosecuted these defendants for rioting at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, precipitating a trial that many Americans, of varying political persuasions, believed was politically motivated. The obdurate obstinacy of Judge Hoffman, the theatrical temperaments of the defendants Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, and the spectacle of Bobby Seale, the only black defendant, bound and gagged in open court because of his insistence on being represented by Charles Garry, his personal attorney, led to a breakdown of all decorum in the courtroom. The five-month trial became a judicial circus, with constant, acerbic bickering between Kunstler, who was the defendants’ lead counsel, and the judge. This 1969 trial thrust Kunstler into national attention.

The average American today only vaguely recalls these names, Rap Brown, Stokely Carmichael, the Berrigan brothers, and of the Chicago Seven: David Dellinger, Tom Hayden, Abbie Hoffman, and Jerry Rubin. However, the late 1960s and early 1970s experienced the heat of the sitins and race riots, Vietnam demonstrations, patriotic exhortations, and returning body bags, the fear in some quarters, and hope in others, of actual insurrection. These individuals were then household words. Among Main Street Americans, a man who would eagerly and enthusiastically represent such persons himself became a pariah. And in the minds of many, Kunstler stayed just that throughout the rest of his life.

Few of those patriotic Americans who hated Kunstler because he represented anti–Vietnam War protesters knew that he was a decorated hero of World War II. In 1941, when he graduated from Yale University after majoring in French, Kunstler underwent extensive dental work. The purpose of the painful procedure was to enable him to enlist in the navy, although ultimately the navy rejected his application twice. He successfully enlisted in the army, volunteered for cryptographic school, served in the Signal Corps under fire in the Pacific, and left the service with the rank of major and a Bronze Star. Few of his detractors would have known that while in the Pacific, Kunstler saved a man’s life (or so the GI remembered it) and once, after a buddy died, searched Japan to find a rabbi to bury him.

If his experiences in the civil rights era began Kunstler’s transformation, the trial of the Chicago Seven in 1969 completed it. In that trial he learned of the FBI’s cynical practice of talking privately with judges to frighten them into requesting additional protection. A courtroom bristling with armed guards would implant the notion in the jury’s mind that here were truly dangerous defendants and thereby create bias before a trial began. In his civil rights work in the South, the federal courts had been friends and allies in the struggle against segregation. Kunstler had believed that there was “essential justice” in the federal courts and that eventually wrongs would be righted. But the Chicago Seven trial was a “dramatic eye-opener that put a tragic twist” on those beliefs. He claimed it was a personal Rubicon.

In Chicago, in the same type of federal court I had relied on for years, I was suddenly confronted by a tyrannical judge, malicious prosecutors, and lying witnesses. It was the shock of my life. . . . It taught me the hardest lesson of my life: The judicial system in this country is often unjust and will punish those whom it hates or fears.

However, because of the government’s use of perjured testimony, its writing of threatening letters to frighten jurors, and its eavesdropping on attorney-client conferences, Kunstler learned valuable lessons. He learned to use the media and publicity for his clients’ purposes, and to use his body, voice, and humor in trial. He learned to follow the political line of his clients, rather than his own, to risk contempt charges in order to fight back against what he perceived was oppression, to become “a battler rather than a barrister,” and to “see the legal system as an enemy.”

As the years progressed, Kunstler’s clients became even more closely associated with violence, but violence in the cause of matters Kunstler and his clients deemed political. Kunstler represented the Attica prisoners during their uprising in 1971 and in the prosecutions that followed. He represented Dennis Banks, Russell Means, and the American Indian Movement (1973–74) and Native Americans Darelle Dean Butler, Robert Robideau, and Leonard Peltier, charged with murdering an FBI agent (1975). Kunstler represented Larry Davis, accused and acquitted of the wounding and attempted murder of six New York policemen (1986); El Sayyid Nosair, accused and acquitted of the murder of the fanatical Rabbi Meir Kahane (1990); and Yusef Salaam, one of the principal defendants in the shocking Central Park jogger rape case (1990).

Kunstler was lead counsel in or participated in many other high-profile cases that earned him considerable enmity. In the 1960s he successfully appealed the conviction of Jack Ruby, the killer of John F. Kennedy’s assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald; in the 1980s he persuaded marine sergeant Clayton Lonetree that he was being prosecuted, for espionage in allowing the KGB to penetrate the security of the American embassy in Moscow, because he was an American Indian, and served as Lonetree’s trial lawyer at his court-martial; in the 1990s he represented Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman, the blind Muslim cleric accused of being the inspiration behind the New York World Trade Center bombing conspiracy; and, until fired by his deranged client, he represented Colin Ferguson, the mass murderer on the Long Island Railroad, and proposed the infamous “black rage” defense.

These are among the more publicly notorious of Kunstler’s cases. The clients themselves would alienate many Americans. Moreover, Kunstler also had the infuriating (to many) habit of ascribing a racial motivation to prosecutions of blacks and other racial minorities. He believed that “our society is always racist,” and that young black men do “not stand a chance of obtaining a fair trial because of the racism inherent in the criminal justice system.” He tried to take on those cases that were “the most difficult, where there is the least chance of an acquittal.” In Kunstler’s view, as the years moved along, Native Americans and then Arabs joined blacks among the most despised groups.

Kunstler’s critique of American racism was combined with a fundamental attack on the legal system. By 1974 he regarded “law in the United States as a charade and a buttress to a system. I happen to think it’s unfair and unfairly applied, that it’s just a terroristic device, in many ways, to keep control of the system.” In the 1960s and early 1970s Kunstler could count on many sympathetic ears, but in more conservative 1982 he drew hisses from Harvard law students when he told them that “law is a control mechanism of the state.” As the New Left movement collapsed in the 1970s, Kunstler never wavered or bent with the wind: he held on to his convictions in the face of mass opposition. In 1994 he addressed a meeting of the New York State Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, and repeated that law “is nothing other than a method of control created by a socioeconomic system determined, at all costs, to perpetuate itself by all and any means necessary, for as long as possible.” The United States Supreme Court was “an enemy, a predominately white court representing the power structure.”

Although Kunstler said all these things, he did not always act on these beliefs. He never became a revolutionary himself. He went to court day after day and argued and cross-examined, he wrote appellate briefs, he acted in every way as though he believed that judges could be convinced, and that, at some level, the system might work. To his dying days he continued to work enthusiastically on legal arguments. Ronald Kuby, his colleague since 1982, believes that Kunstler had “an abiding faith that people were fundamentally good,” even federal judges. He may have believed that the legal system was the enemy, but there were many other enemies too, and to some degree the legal system could function fairly. At the level of rhetoric, however, Kunstler was always unrepentant of his 1960s and 1970s radicalism, even unto his old age.

Kunstler knew that he was despised by many people. The cases he took sometimes caused friction among his colleagues at the Center for Constitutional Rights. Some generated criticism among the Jewish community, especially vehement at times because Kunstler was Jewish by birth. Some even caused contention within his family. He ignored the criticism and put it aside. Nor did threats of judicial contempt or censure from the various bar associations deter him. Neither judicial anger nor public anger bothered him, and he believed that “lawyers must take chances with their liberty, and with their licenses, to advance their client’s political views.” He acknowledged, “I pay a steep price for what I do, some might think a ridiculously steep price, but it’s my life, and I’m willing to pay it. Sometimes I lose friends; sometimes I bring down the wrath of my family on my head. But I always do what I believe is correct.”

A central paradox of Kunstler’s life was that he was a man who desperately wanted people to love and admire him. At the same time, he did things and made statements that he knew fully well would cause much of the public to despise him. Kunstler was a man who craved love and harvested hatred.

Few of Kunstler’s many detractors would have known of his sense of humor. When a man called him and asked, “Are you the William Kunstler? All the other Kunstlers I’ve been calling have been hanging up on me,” he answered in his bass voice, “I’m the one who won’t hang up on you!” His humor even played on the intense public hatred. He delighted in responding to verbal assaults. If someone recognized him on the street and angrily shouted, “That’s William Kunstler,” Kunstler would turn around and say, “Where? Where? I hate that son of a bitch! Where is he?” His personal charm had a disarming effect on his critics. One quieted critic recalled that he spotted Kunstler across a quiet street in the West Forties: “I yelled, ‘William Kunstler, you’re a jerk!’ Quickly turning his head, he stared and yelled in reply, ‘So are you!’ Then, without missing a beat, he waved. I waved back, astonished at what I was doing. Whatever personal feelings people may have about his practice of the law, everyone must agree that he had style.” Ronald Kuby recalls that “Bill lived his life with a tremendous amount of joy, as pure a joy as I’ve ever seen in anybody. He viewed most things with a tremendous amount of amusement, as serious as he was, including himself. He saw the humor in his own conduct as well as that of others.”

Kunstler’s critics would not have known of his gusto for life. Kunstler loved opera, classical music, and Cole Porter. In his younger years he went to the Metropolitan Opera in New York; later he listened to opera at home. He was always trying to convert his colleagues to his passion for serious music. In the 1960s he dragged his partner, Arthur Kinoy, to classical music concerts, but apparently did not make a convert of him. In the 1980s Kunstler tried to interest Kuby in the pleasures of opera, with somewhat more success. Kunstler enjoyed hamming it up singing Puccini duets with Mario, the produce man at Balducci’s, a grocery around the corner from his home. A favorite opera was Tosca, appropriately enough, since its plot follows the fate of a nineteenth-century revolutionary.

Those who hated him would also have missed Kunstler’s warmth and compassion. He walked around on the streets and would see people he knew or wanted to meet, and often invited them into his home for coffee. He talked with his neighbors, with the street people, with reporters, with clients, and he kibitzed with the waiters at the Waverly Restaurant, a nearby coffee shop. He helped neighborhood panhandlers settle disputes over choice corners. A neighbor recalls,

I so loved the chance sightings on the street! I would often see him coming down the sidewalk with his head down, walking briskly. I’d muster up my courage to say “Hello, Mr. Kunstler!” as he passed. Sometimes he seemed to be totally wrapped up in thought and not respond. Then inevitably he’d pass, and a moment later I’d hear a voice call out, “Well, hellooooo!”

Kunstler called Greenwich Village home for the last twenty years of his life, and in particular that part of the Village centered around Sixth Avenue. He lived and practiced law in a small brownstone located at 13 Gay Street, a short distance west of Sixth Avenue. Upstairs was home; the law offices were the basement, enough for Kunstler, his partner, a student intern, and a secretary or two. Kunstler’s office, “an impenetrable warren of books, papers, sprung couches, and bric-a-brac,” was to the front, toward the street. Without his booming voice and animating spirit, the quarters might seem gloomy, perhaps dingy.

Typically, Kunstler got up early in the morning, made coffee for himself and Margie, his wife, and went down to his office to begin work by 7:00.* He did paperwork until 8:30, together with Ronald Kuby, his partner, who came in at 8:00. About 8:30 they began gathering their papers together for court, where they often spent the day trying a case, grabbing junk food for lunch, rare hamburgers or bacon sandwiches, washed down with white-and-black sodas. At the end of a trial day, Kunstler often held a press conference, then dashed back to his office for a...