![]()

1.

BEGINNINGS

A GLARING, blinding sun. Damp, clammy heat. Dust often as thick as fog. Except for a narrow strip of carefully tended shrubs and flowers in the median strip of the highway leading from the airport to the capital, the entire region seemed devoid of vegetation. Odd-shaped rocky hills and plains lined the entire thirty-seven kilometers of road linking Sib Airport with the port of Matrah, the capital area’s older center of trade and commerce, and Muscat, the old, walled administrative center. Elegant villas, shops, and tall apartment buildings in various stages of completion rose from this barren, moonlike environment. The appearance of Matrah’s waterfront, a row of white buildings, modern and old, set off by a newly constructed corniche and the blue sea, was comforting because it was more familiar. The smell of fish mingled with that of car fumes. In the distance, I could just make out oil tankers riding at anchor. It was one o’clock on a day in early September, and few people were in the streets. Our guest house in Matrah, nine years old but the oldest in Oman, catered mostly to Arab, Indian, and Pakistani businessmen. It was run more like a rooming house than a hotel, and the staff, mostly Indian, were delighted with the presence of our nineteen-month-old daughter. Guests who brought children along were rare, and the families of the staff were back in India.

Three days later we moved temporarily to Ruwi, a new town created in the early 1970s in the valley, inland from Matrah. There we settled into a comfortable apartment generously loaned to us by an Omani who was on vacation. We remained there until we were able to make the necessary arrangements for our move into the interior, where we were to conduct anthropological field work.

I found Ruwi very different from other Middle Eastern cities that I knew. Barely ten years old, this extension of Matrah depends completely on motor transport. The dust, the uneven ground, the lack of sidewalks, large distances between buildings, and the heat made walking arduous and virtually impossible for women like me with small children. Save for some Indian servants and workmen, few people were on foot. Looking out of my apartment windows, I could see barren hills, a highway, and the side of another apartment building that was a replica of ours. The city was silent. Where were the street vendors, the children, the small shops, the crowds of men, the blaring radios, the prayer calls, and the women on their balconies or roof terraces so characteristic of neighbor-hoods in other Middle Eastern and North Africancities? While my husband met various officials and arranged for housing in the interior and the purchase of a car, I remained alone with my daughter for long stretches of the day. We were lonely.

There was a modest but adequate bus service between Ruwi and Matrah, used mostly by Indians. I went a few times to the Matrah market, carrying Amal, my daughter, and a thermos of water. No one paid much attention to me in my cotton blouse and maxi skirt, with a kerchief covering my hair. Merchants were courteous. Buying was straightforward with no bargaining, unlike elsewhere in the Middle East. The sidewalks were busy without being overly crowded. Many men wore elegant, dazzlingly white, long tunics (dishdāshas), their heads covered with skullcaps or turbans. Others wrapped a checkered Madras skirt (wizār) around their waists, with a T-shirt above. Save for some young Indians wearing European trousers and close-fitting shirts, no men wore Western-type clothes. A few women were in the downtown market area as well, some wrapped from head to foot in long black cloaks (’abāyas), but not all women wore one. I have the vivid image in my mind of a woman on Matrah’s main street carrying a young child in her arms and walking a few feet behind a man. She wore a shawl and a boldly patterned tunic over embroidered pantaloons. The brightness of the synthetic fabrics made me observe her a few seconds. Suddenly she turned toward me and gave me a wide, friendly grin. I could not yet tell from her clothes to what ethnic or religious group she belonged, but I knew that Oman’s coastal population was extremely diversified. There were Arabs, Baluchis, Liwatiya, Persians, Indians, and people of African origin. The population was also divided along religious lines: Sunni Muslims, Ibadi Muslims, Persian Shi’i Muslims, Indian Shi’i Muslims, and some Hindus. There were also many foreigners: Egyptians, Jordanians, Saudis, East Africans, a sea of Indians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis, and—rarely on the streets—a scattering of Europeans and Americans.

Late afternoon and early evening are visiting hours in the area around Muscat. We were invited and received extremely well by many people during our first few days in Oman. I asked many of the women I encountered for information about what food and supplies I would find in the interior, but no one seemed to have spent more than a few hours away from the coastal area. Many of the men were equally uninformed. Some persons spoke of the harsh material conditions we would find, the poor distribution of food, the heat, the difficulties of living without electricity. I began to worry.

Soon I met my close neighbors in the apartment building. Amal played regularly in the lobby, which was cool and well ventilated, and other children came to join her. I was immediately drawn to my young and smiling neighbor Rayya, and I think she reciprocated my feelings. Her clothes were a sea of large, bold designs, in the brightest colors, which to me seemed to have been chosen to compensate for the bleakness and lack of color in the natural landscape. Rayya was shy at first, but soon she became vivacious and talkative when she realized that I understood Arabic. She came from Sur, a coastal city to the south, had four children, and had lived for five years with her husband in Abu Dhabi. She invited me in for tea, recognized how lonely I was, and soon introduced me to her morning activities. No other “Europeans” lived in the building or the immediate neighborhood. She showed me her clothes and snapshots of her relatives in Sur, and taught me how to cook rice and fish Omani style. We discussed children at length, and I helped her prepare school clothes for her eldest daughter, who was entering first grade that fall.

Rayya introduced me to my first coffee-drinking session with some of the women of the apartment building. One of these women was the wife of Shaykh Sa’id of Hamra, the oasis where we were planning to do our fieldwork.1

September 19. Shaykh Sa’id’s wife and daughter again visited one of the neighbors on our floor, a family from Qal’a. They came around noon, when most of the cooking was done, but before their husbands were expected at the end of the government workday of two P.M. Shaykh Sa’id’s wife was wrapped loosely in a black ‘abaya and carried a large tray of fresh dates on her head. Her daughter, around sixteen, wore a light blue veil, a tunic, and machine-embroidered pantaloons, and carried a large thermos of coffee. The lady from Qal’a invited Rayya for coffee.

Since I was present, I was also invited. We ignored the Western-style couch and armchairs, standard government issue, and sat instead on a large carpet. There were no introductions. We were served mouth-watering fresh yellow dates and sliced bananas. Coffee was poured into a small Chinese cup, and each of us took a turn drinking. As long as I did not refuse the cup, it was refilled and returned to me. Part of the conversation was about a film on television the night before, although I had difficulty in understanding some of the things said. Shaykh Sa’id’s daughter commented on my clothes and how plain they were. There was also talk of eye infections. Rayya brought out her daughter’s new school uniform, which everyone admired. Shaykh Sa’id’s wife did not speak to me directly but seemed to find my presence amusing. Every time I spoke she looked at me with a twinkle and seemed to suppress a peal of laughter.

Later I asked Rayya whether she knew many women in the building. “No,” she answered, “just these women.” Yet her balcony had a view of the entrance lobby to our building, and she could name me many others. She did not think highly of the family from Qal’a, although she visited them when Shaykh Sa’id’s wife came. She privately complained to me about the children, their dirt and their lack of manners (adab).

She told me Shaykh Sa’id’s wife was named Miryam and that whenever she visited, she brought large trays of dates and other fruits that she left behind. I had seen a similar plate of dates in Rayya’s refrigerator and wondered how many people Miryam visited in this flamboyant manner. Was this distribution of fruit one of the duties of being a shaykh’s wife? How did one become part of a visiting network?

In addition to Rayya’s family and the other from Qal’a living on our floor, there was a bachelor (our absent host) and a Jordanian family in a fourth apartment. The Jordanians received us very hospitably. Dale knew the husband through his ministry friends, arid Amal played with their children. The wife, a schoolteacher who was not home for extensive portions of the day, never took part in these coffee-drinking sessions.

The apartment building next to ours housed police officers and their families. A small playground next to our house was reserved for their use. I used it, unaware at first that it was restricted. Amal and I found it difficult not to go out for long stretches of the day. In the late afternoons it was the only area where we could be outside with other children. Within a week we became accepted at the playground and I met other women from the interior.

September 19. On arriving at the playground, women shake hands with those already sitting down, exchanging polite, barely audible greetings. They are quite formal, and conversation is general and not very intense. Many women sit alone silently, some embroidering head caps (qimmas) for men. Today I went around the playground and shook hands with everyone, just as the others were doing. I spoke with two young sisters who came from Nizwa, the largest oasis of the interior and close to where we wanted to live. One lives in Matrah, the other in Ruwi, and they visit each other regularly. We introduced ourselves and talked mostly about our children. They seem to return regularly to Nizwa.

September 24. Now I automatically receive the ritual handshakes from new arrivals. Small talk with some women more talkative or curious than others is more frequent than it was a few days ago. Do I have only one child? Am I pregnant? Where do I come from? What does my husband do? Do I work? Today I was taken for an Egyptian, which surprised me, given my thick accent in Arabic with a French overlay. When I said I came from America, I heard someone say that Americans were “good” (kwayyis), using the Egyptian word.

September 27. As soon as I arrived in the playground, a tall, handsome woman of about my age came up and invited me to her house. A Baluchiya from Matrah with six children, she has been living in the police complex for the last five years. She told me that other women in the building came from all over Oman. They all know one another and visit often. She knew my neighbor Rayya by name, as well as Rayya’s eldest son. After coffee, we returned together to the playground, where we shook hands all around. Some women no longer stare, and one woman even asked me where I had been for the last two days. “We have been visiting,” I answered, smiling.

Rayya and I saw each other frequently during the three weeks preceding our departure to the interior. We drank coffee three times with Miryam, twice in the apartment of Fadila, the woman from Qal’a. The last time, the visit took place on a lower floor in the apartment of a woman from Rustaq, a large oasis about one hour away from Muscat. This family was obviously of a higher status because the coffee-drinking session was more elaborate and formal. This was to be my last contact with women of the interior living in the capital before our move to Hamra.

October 2. Around 11:30 A.M., Fadila invited Rayya and me to drink coffee downstairs with Miryam. Our host, a woman from Rustaq, had an older woman at her side who looked like her mother. This time the fruits were provided by the people from Rustaq—large trays of bananas, watermelons, dates, and coffee. Miryam was offered the first cup of coffee. Fadila was offered the second cup but refused, insisting that the older woman from Rustaq be served first. Then Fadila was served, followed by me and Rayya.

The television was on, and some children were crying, which made it difficult for me to follow the details of the conversation. Mir yam was talking about me in a corner. They also discussed clothes for the coming feast and offered tips on how to take care of children’s hair. “You will eat a lot of meat during the feast in Hamra,” Miryam ventured, addressing me directly for the first time. Incense was burned in a small charcoal brazier, and a tray of perfume was placed before us. Everyone applied a little perfume on themselves from each bottle. As I was leaving the apartment, I noticed two young girls in their teens who had stayed quietly in the bedroom and had not taken part in the coffee-drinking session. They smiled at me and Amal.

We left for the interior on a Friday morning. Our small car was packed tightly with suitcases, a typewriter, tinned and dried foods, pots, pans, and other household goods, and a month’s supply of disposable diapers. The road stretched before us in a straight line through a rocky plain with sparse vegetation, flanked by hills of bare rocks. The road began to curve more as we entered the Suma’il Gap, the traditional route that cuts through the Hajar mountain range and provides access to Nizwa. I still had little idea of what was behind those hills.

As we passed small oases with their mud-brick houses and tiny patches of gardens and date palms, I tried to imagine what Hamra would be like. Traffic was not heavy, but occasional roadside shacks selling soft drinks and gasoline stations indicated that the road was regularly used. I had an odd mixture of feelings: relief to be leaving the humid heat and barren landscape of the capital area, sadness for leaving some people behind, and anxiety and curiosity over what would happen next.

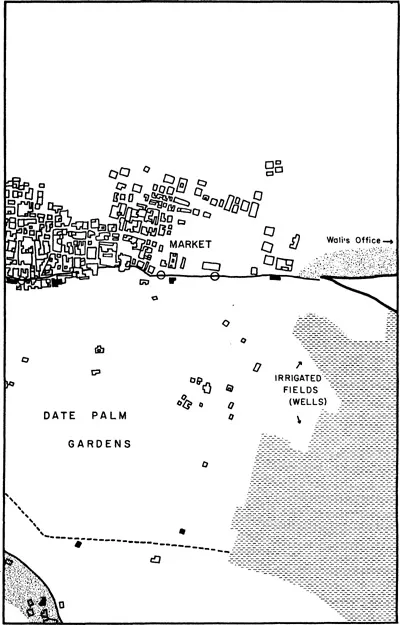

Two-and-a-half hours later we arrived at Nizwa, the largest oasis of the interior and until 1955 the capital of the Ibadi imamate. Nizwa is a vast oasis, with gardens of date trees and at its center, next to the crowded market, a large, stone fortress. Nothing I had seen earlier on the road prepared me for its size. The road skirted the market area, packed with people, animals, and flimsy fruit and vegetable stands in front of the most established shops. Its parking lot was filled with cars and trucks, and traffic slowed to a crawl.

Just over twenty kilometers past Nizwa, we turned sharply to the right. A green sign marked “al-Hamra” pointed to a feeder road, which, like the main one, was obviously new. The paved road leading to Hamra was not yet built when Dale first visited it the year before. By now, in addition to the barren hills on either side of the road, we could see the Jabal al-Akhdar, or “Green” Mountains, in front of us. We drove for about twenty minutes. Then the paved road was replaced abruptly by a gravel one. We climbed the rough gravel road up a hill. Just over its crest I got my first view of the oasis of Hamra, nestled at the foot of an enormous, grayish-green rock devoid of vegetation. Compared with its immediate surroundings, Hamra appeared lush and fertile, a small green jewel.

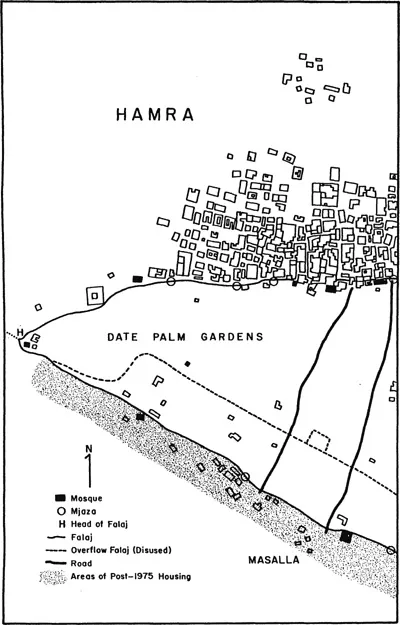

Figure 2. Map of Hamra. Based on sketch by Dale F. Eickelman from a 1976 aerial photograph. Base: V5 SOAF986 50mm. × 2.

We drove on, passing a small hill with a dilapidated stone watchtower, a relic of a not-too-distant period when tribal warfare was endemic. Finally, we reached the date-palm gardens. Only the orchards separated us from the main part of town. We had to circle the gardens on a narrow, dusty road, which followed the falaj, or irrigation canal, on the edge of the gardens. On the other side of the road there were small houses. Many seemed to have been built fairly recently because they were made of cement, but all were modest in appearance.

We arrived in Hamra at noon. Few people were outside. A man wearing a Madras cotton wizar and a woman in a large, fringed colorful shawl, long tunic, and pantaloons looked at our car curiously. We stopped next to a small white mosque shaded by an enormous tree. A few children were bathing in the falaj next to it. The water seemed cool and inviting. We entered the gardens on a narrow path with a branch of the falaj and high mud-brick walls on either side. Fifteen yards in we came to a new metal door, brightly painted in green and yellow. It contrasted sharply with the crumbling mud wall in which it was embedded. This was the entrance to our new home: three separate buildings with a small cement courtyard. One building was a narrow, long room for receiving guests, the sabla; it had a small private room at one end. Another building was a kitchen and bathroom. The third contained a large room, which we used for sleeping. The other rooms of this building, to which we did not have access, were reserved for the use of the landlord’s family. They had earlier been used by his grandsons, who were now studying in the capital area.

The contrast between our new home and our Ruwi apartment of the previous three weeks was staggering. Here we were surrounded on all sides by vegetation. Lime trees, banana trees, and date palms shaded the courtyard and buildings and made them wonderfully cool. Because repairs to our compound were not yet completed, the courtyard was in great disorder. Tools were strewn about, and there was a pile of sand in one corner. An enormous kerosene refrigerator that turned out to be broken lay on its side in another corner. Limes had fallen from the trees and had not yet been picked up.

Soon after we arrived, we were greeted formally by Shaykh Abdalla Muhanna al-’Abri, the tribal leader of the Abriyin, who was also our landlord. Shaykh Abdalla was in his sixties, with a white beard, and dressed in a spotless white dishdasha girded at the waist with a leather belt, a silver dagger, and a submachine gun. Coffee and dates were served, and we were then led back to his car, on the road near our house, for lunch at his house.

Shaykh Abdalla, like many other notables of the Abriyin, lived in a large, fortresslike mud-brick house that directly faced the orchards and was next to the falaj. A television aerial was visible from his roof terrace. We were led into a very dark first floor and into a long, narrow guest room where several men were sitting. It looked like the beginning of a formal meal; so I immediately asked the shaykh to introduce me and my restless two-year-old to his family. This turned out to be the right thing to do. As I began to follow a young man up an extremely narrow, dark, and uneven stone stairway, carrying Amal in my arms, someone whispered, “She knows.”

I entered a large, poorly lit room that had a dirt floor. At one end low windows with metal bars gave some light, and carpets had been spread next to the windows. The room looked like a large vestibule. Doors on either side led into side rooms. In the center stood a tank of water with a small tap for washing. Save for the carpets, probably of Indian origin, and a ceiling fan that was not turned on but that indicated the presence of an electric generator, the room was devoid of furnishings and wall decorations. Nothing seemed to point to the high status of our host.

Amal and I were expected. About ten women of all ages immediately surrounded us. What I noticed first was that many of them had their foreheads and upper cheekbones daubed with a dark red...