![]()

1

Material Life in West and West Central Africa, 1650–1800

But when all the criteria of civilization have been considered—language and communication, technology, art, architecture, political, economic and social organization and ideological developments—it can be said that the available evidence, however fragmentary or circumstantial, does suggest that the Akan sometime between A.D. 1000 and 1700 progressed rapidly from the level of peasant agricultural communities to the level of urban societies and principalities, culminating in the establishment of an indigenous civilization.

—James Anquandah, Rediscovering Ghana’s Past (1982)

Needed for more than brute labor on New World plantations, African workers carried agricultural and craft knowledge across the Atlantic that transformed American “material life,” a concept defined by economic historian Fernand Braudel. In the first volume of his monumental study Civilization and Capitalism, Braudel underscored the significance—then overlooked by most historians—of daily material human needs and economic activities. Looking at economic production in the early modern world, he treated as subjects of historical investigation the foods people ate, the clothes they wore, the tools they used, the markets where they conducted trade, the cities they established, the dwellings they inhabited, and the household furnishings they possessed. Within these structures, human actors lived a “material life,” meaning “the life that man throughout the course of his previous history has made part of his very being, has in some way absorbed into his entrails, turning the experiments and exhilarating experiences of the past into everyday, banal necessities.”1

Given the role that African workers played in material production in the Anglo-American colonies, the concept of material life offers a useful tool with which to explore the historical contexts out of which Africans emerged and to assess their role in New World plantation development. What was the nature of West and West Central African material civilization during the era of the slave trade, how did it come into being, and how did it vary over time and space? What made African material life different from that of other regions of the world? What forces shaped its development? How did Africans perceive the process of material production? This chapter will address these questions, highlighting ways that people in West and West Central Africa produced and reproduced their daily material needs during the height of the Atlantic slave trade. Looking at more than the technical aspects of material production, it will also explore the social, political, and ideological structures through which West and West Central Africans conducted their material lives. In particular, this chapter will demonstrate that Africans acquired a wealth of knowledge through their daily life in urban centers or rural communities, their trading practices and social networks, and their fishing, mining, and artisan practices. The people tragically ensnared by the Atlantic slave trade carried this knowledge with them to the American colonies, and their experience provided them with an important compass to navigate their way through their New World environments.

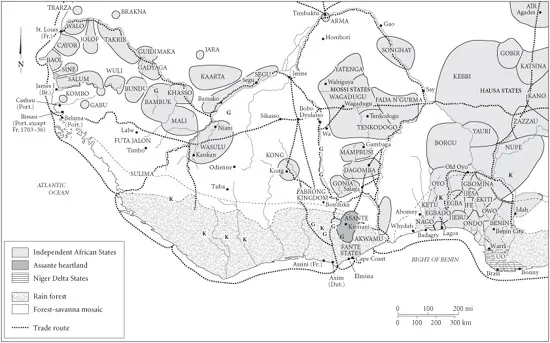

At the advent and during the height of the Atlantic slave trade, European merchants tied into West and West Central Africa’s preestablished social and economic networks. Starting with the gold and pepper trade, they turned to buying slaves on the African Coast. In their log books, ship captains generally labeled their captives as generic commodities.2 However, enslaved Africans emerged from much more dynamic contexts than such terminology suggests. Indeed, African captives had deeply embedded ties with others through local or long-distance trading networks, which underwent significant change during the years of the slave trade. For example, both internal and external factors shaped West African trading networks during the Atlantic slave-trading era. One of the most important internal factors that influenced trading patterns was political decentralization. In 1591, an invasion from Morocco brought the collapse of the Songhay Empire, centered on the Niger Bend. Songhay had previously dominated West Africa’s long-distance trade across the Sahara, which tied the West African forest regions to northern suppliers and markets. Merchants in cities and towns such as Timbuktu, Gao, and Jenne and surrounding plantation complexes along the Niger River facilitated long-range commerce. However, with Songhay’s demise, economic power shifted west into the Senegambia region, south into the forest and coastal zones, and east into Kanem-Bornu. During this period, Muslim merchant associations such as the Wangara, which survived the collapse of the Songhay Empire, moved a variety of commodities throughout West African and other commercial networks.3

Underlying the large-scale commercial networks and long-distance trade of the Wangara and others stood a system of daily market activities carried out by small-scale traders. “Markets were ubiquitous in West Africa,” notes anthropologist Elliot Skinner. “The markets served as local exchange points or nodes, and trade was the vascular system unifying all of West Africa, moving products to and from local markets, larger market centers, and still larger centers.” Small-scale, local traders set up daily markets that offered foodstuffs and other staple goods, while peripatetic traders moved periodic markets from town to town, returning in three-, four-, five-, or sixteen-day intervals. As agents of West African material life, traders facilitated the exchange of material commodities and, more broadly, ideas and “cultural goods.”4

Elites and peasants, agriculturalists and artisans, country folk and town dwellers, and women and men encountered each other daily in these urban and rural trading centers, which allowed people to establish or transgress social and cultural boundaries. For example, at the turn of the seventeenth century, peasants, particularly women, traveled considerable distances to trade between the Gold Coast and its hinterland. The Dutch factor Pieter de Marees recorded that on a market day in Cape Coast

the peasant women are beginning to come to Market with their goods, one bringing a Basket of Oranges or Limes, another Bananas, and Bachovens, [sweet] Potatoes and Yams, a third Millie, Maize, Rice, Manigette, a fourth Chickens, Eggs, bread and such necessaries as people in the Coastal towns need to buy. These articles are sold to the Inhabitants themselves as well as to the Dutch who come from the Ships to buy them. The Inhabitants of the Coastal towns also come to Market with the Goods which they have bought or bartered from the Dutch, one bringing Linen or Cloth, another Knives, polished Beads, Mirrors, Pins, bangles, as well as fish which their Husbands have caught in the Sea. These women and Peasants’ wives very often buy fish and carry it to towns in other Countries, in order to make some profit: thus the fish caught in the Sea is carried well over 100 or 200 miles into the Interior.5

Map 1. West Africa, ca. 1700

Guided by these daily rhythms of exchange, West African women linked specialized areas of food production between the coast and inland. They also acquired knowledge of multiple environments and economic activities.

Whereas women generally carried out the trade in foodstuffs, male traders such as the Wangara plied more prestigious commercial goods. They moved commodities including gold, salt, and kola nuts, used as a stimulant and to abate hunger and thirst, through West African trading corridors. By at least the fifteenth century and into the sixteenth century, the Wangara, an association of Muslim traders from the Niger Bend area, monopolized the trade between North African salt production centers and West African kola nut fields and gold mines. Supplying the external demand for West African gold, merchants mobilized free, slave, or peasant labor in alluvial or pit mines in Bambuk, Bure, Lobi, and the Akan forest gold fields. Adjacent to these gold-mining centers, peasant and slave labor harvested kola nuts that stocked kola markets in the savannah, the Sahel, and the Sahara Desert. Caravans laden with gold and kola nuts moved northward from the forest region. In exchange, caravans loaded with different commodities, including salt from the North African salt mines of Taodeni, Teguida, N’tesemt, Idjil, and Awlil, supplied southern markets. According to one estimate, workers at the production centers in the Lake Chad basin yielded up to thirty thousand tons of salt annually during the sixteenth century, supporting the daily needs of four to five million people.6

Facilitating the flow of commodities, traders exchanged a range of currencies that circulated throughout West Africa’s “vascular system” of trade. Large merchants, small traders, and consumers used different kinds of currencies, including gold, cotton cloth, and iron bars, which were exchangeable at fairly consistent rates over time. At the high tide of the Atlantic slave trade, West Africans used cowry shells from the Maldive Islands in the Indian Ocean as currency. During the eighteenth century, British and Dutch trading firms shipped 25,931,660 pounds of cowries to West Africa, amounting to approximately ten billion shells that entered into the system of trade and circulated throughout the region.7

Through this ongoing process of trade, West Africans tied together production centers, towns, villages, and hamlets. They also acquired experience in managing and transforming the material world, experience that, though intended for local use, took on particular significance within the context of the Atlantic slave trade and New World slave labor camps. Through pathways and “webs” of trade, West Africans brokered and reproduced social and cultural differences. In the process, they reproduced their material lives in mining centers and agricultural fields, in village markets and larger urban settings, through trade in gold or cowries, and by way of local trade or long-distance caravans.8 Hence, when European merchants first arrived on the West African coast in the fifteenth century, they encountered societies with well-established commercial networks. Over the following centuries, the Atlantic trade tapped into, redirected, and prompted changes within these market networks.9

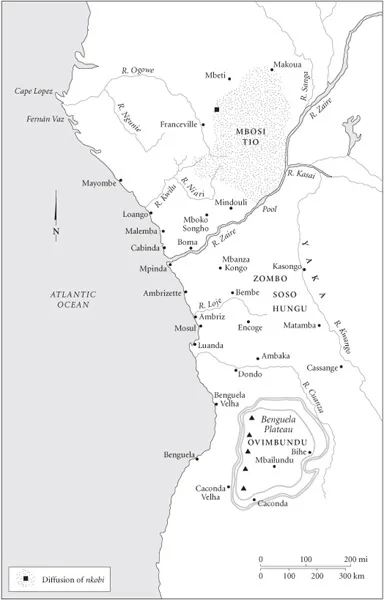

People from Central Africa who were captured in the slave trade came from parallel trading worlds. Most of the exchanges of goods in Central Africa took place on a small scale and were used to cement relationships with people within one’s community. Workers in fishing communities exchanged their catches for staples produced by agricultural labor. Leather workers and cattle herders from the savannah region of Central Africa sent their goods to their northern neighbors. Agriculturalists acquired additional protein by exchanging food staples for the game caught by hunters. Salt, iron, and copper workers found outlets for their products. And while most production was geared toward use within the context of local communities, Central Africans were also bound up in trading relationships with people outside their immediate environs. A small group of people engaged in commerce as their primary occupation, a trade not bound to the ties of community and kinship within which much of the exchange in Central Africa took place.10

The exchange networks of West and Central Africa developed along similar lines, with rotating markets and currencies flowing through each. In the coastal and central regions of southern Central Africa, a four-day market system operated, in which traders traveled to four different market villages over a week. In other places, as for one market along the Zaire River, markets opened once a week. The currencies that flowed through these markets included shells (nzimba) from the Central African coast, raffia cloth (lubongo), and iron bars, a set of currencies comparable to those circulating through West Africa, where people used cotton textiles, iron bars, and later cowry shells as currencies. As a sixteenth-century chronicler of the Congo stated, “Colorful shells the size of chick-peas are used as money. … In other regions, this shell money does not exist. Here they exchange fabrics of the type used for clothing, cocks, or salt, according to what they want to buy.”11 In their encounters with people on the Central African coast and in towns such as Mbanza Kongo, Portuguese merchants tapped into these local networks of patronage and trade.

Map 2. West Central Africa, ca. 1700

The interaction between Central Africans and European traders altered these internal networks. In particular, the massive infusion of trade goods brought in through the Atlantic trade at Luango, Benguela, Luanda, and other Central African ports provided local elites with the means to expand their patronage networks. By distributing foreign rum, imported Asian and European textiles, and other material goods, African patrons expanded their client base and cultivated allies. Access to these new materials created opportunities for the rise of a new elite. In many cases, patrons entered into debt to acquire the goods they needed to expand their retinue, which enabled them to extend their local power base while also making them vulnerable to the demands of creditors. This system of debt became cancerous, as some local elites further extended the system of credit to less powerful vassals. As African patrons and vassals became overextended on foreign credit in the form of trade goods, many saw that their only way to dissolve their debt was to raid for slaves in neighboring territories or to sell people from within their own domain whom they deemed to be expendable. Through such means, the trading networks of West Central Africa were transformed and generated slaves for the Atlantic slave trade.12

In West and West Central Africa, local, regional, and long-distance trading networks linked people across wide expanses, creating a flow of not only material goods but also knowledge. As merchants carried salt from the Sahara Desert into the West African forest, gold and kola nuts from the forest into the Sahara and the Mediterranean World, hides from the Central African savannah to forest agricultural communities, or copper from the Central African mines to its towns and villages, they carried information and ideas about production and the natural world. So people in the regions hit by the Atlantic slave trade had knowledge that was particular to their local social and natural environments, yet they also had an awareness that went beyond what was essential to survive in their immediate surroundings. Out of these environments, networks, and ways of knowing, West and West Central Africans created their material lives.

The web of West African trading relationships connected a population estimated in 1700 to be approximately twenty-five million people, the vast majority of whom lived in rural communities.13 However, trade bound the countryside to urban areas, which had a long history in West Africa.14 Through the confluence of external and internal trade, the towns of Timbuktu, Jenne, Gao, Koumbi-Saleh, Niani, and Kano in the West African savannah emerged in the first and early second millennia AD. Toward the end of this period, towns arose in the south, particularly Begho, on the savannah-forest fringe, and Old Oyo and Benin in the West African forest zone. These towns attracted local trade, linked forest and coastal villages to larger trading networks, and served as “ports” of commerce between the West African forest and savannah-zone economies and the Sahara Desert and Mediterr...