![]()

1

Buying into the Cool Sell

Cool is the opiate of our time.

—Kalle Lasn1

For much of the 20th century, marketers relied upon the conventional weaponry of the mass media to deliver their commercial payload: newspapers, magazines, radio, television, and billboards structured the information environment and furnished the primary venues for the placement of paid advertising. Within that environment, advertisers jockeyed for attention in predictable, delimited contexts through persuasive campaigns that could be clearly and openly identified as such. By and large, we knew what advertising looked like and we knew where to find it: during the programming break on TV, surrounding the editorial content in a newspaper, or across banners atop a webpage.

At the dawn of a new millennium, however, thanks to profound upheavals in technology, markets, commercial clutter, and audience expectations, that traditional model seems to be crumbling in slow motion. Given those challenges, marketers are exploring new and reimagining old techniques of communicating messages in the hopes of somehow managing consumer audiences and bleeding out promotion from previously confined, more readily apparent media spaces. These innovations and reinventions—many reflecting an ethos of public relations as much as advertising—proffer a solution to an industry ever-evolving by deploying commercial appeals more intended to slide “under the radar” of audiences rather than announcing themselves forthrightly. They represent, in a sense, an effort at a new breed of “hidden persuaders” optimized for 21st-century media content, social patterns, and digital platforms.

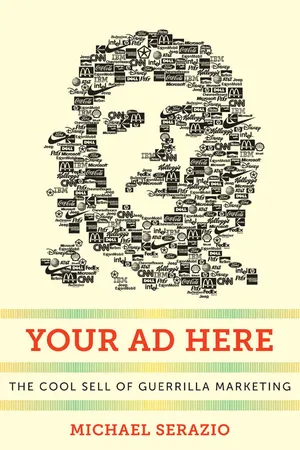

Your Ad Here takes these techniques of commercial self-effacement seriously—examining them to uncover and map the institutional discourse, cultural logic, and technological context underpinning such “invisible” consumer governance: that is, the subtle way in which desire might be orchestrated and the agency of imagined subjects might be positioned in order to get them to shop. By exploring the practice of “guerrilla marketing”—the umbrella term here for a wide assortment of product placement, alternative outdoor, word-of-mouth, and consumer-generated approaches—we might better understand a new media environment where cultural producers like advertisers strategize and experiment with persuasion through increasingly covert and outsourced flows. By looking at a diverse set of campaign examples—from the America’s Army video game and Pabst Blue Ribbon’s hipster “hijack” to buzz agent bloggers and tweeters and Burger King’s “Subservient Chicken” micro-site—we can appreciate how Madison Avenue is now thinking through technology, subculture, and audiences.

A caveat of emphasis is warranted right from the start: This is not a book about audiences directly, yet the discussion of audiences (and, most especially, millennial audiences) will figure prominently throughout. This is, in a sense, a second-order study of audiences—of how marketers and the producers of cultural content at the beginning of a new media era think about them and attempt to exercise power in today’s consumer society. That governance will sometimes succeed and will sometimes fail, but here, too, I elide inquisitions into and declarations of actual effect in favor of an intense focus on “encoding” effort—that first stage in the commercial process that is, at once, essential to understand and yet critically understudied.

As befitting a public relations mind-set, the guerrilla message these marketers seek to seed travels “bottom-up,” through invisible relay and from decentralized corners in order to engage audiences in seemingly serendipitous ways. The consumer engagement and commercial discovery meant to be orchestrated through such strategies reflects an “exercise of power [that] is a ‘conduct of conducts’ and a management of possibilities” without any semblance of force, intervention, or determination in managing that conduct.2 Thus emerges a regime of governance that accommodates yet structures participatory agency; self-effaces its own authority and intent through disinterested spaces and anti-establishment formats; opens the brand up as a more flexible textual form; and democratizes and decentralizes in favor of populist collaboration. It is, in short, advertising not meant to seem like advertising.

Audiences, these strategies suggest, might be governed differently in a 21st-century networked media world: Their agency can be presupposed and coordinated as part of the formula for cultural production. The exercise of “push” media addressed audiences comparatively imperiously, while “pull” media, by contrast, deliberately accords liberty and complies with the interactive (and autonomous) choice that ensues. Advertising based on that invitation (i.e., pull) rather than interruption (push) presumes to flatter the capacities of a free subject more conspicuously and then utilizes subsequent contributions to more effectively and individually tailor a message to that subject. In so doing, this further separates the “mass” in “mass media”—usefully so, for cultural reasons, because whatever remains of that mass audience carries with it an indelibly “mainstream” connotation that the guerrilla advertiser tries to avoid by opting for channels that exude a more underground ethos (a valuable pose to strike when catering to millennials, who are routinely conceptualized as jaded, resistant consumer targets).3

To be certain, guerrilla marketing has a relatively narrow designation and comparatively exclusive usage within the industry; it is clearly not the dominant form of advertising media outlay when it comes to budgets and, by and large, courts youth niches more than any other demographic. Practitioners would probably most commonly recognize it as the label for only the variety of out-of-home stunts examined here in chapter 3. The term itself appears to have originated in the mid-1980s in the title of advertising executive Jay Conrad Levinson’s best-selling book, Guerrilla Marketing.4 Nonetheless, by expanding the scope of this label to encompass a range of marketing phenomena not typically termed “guerrilla,” we can better appreciate the philosophy of governance that accompanies diverse promotional tactics. For product placement, word-of-mouth, and crowd-sourced campaigns equally merit conceptual claim to the “guerrilla” label, and by studying the inspirations, machinations, and deliberations behind them, we can identify and analyze common themes of power and practice that seem to animate otherwise disparate advertising executions.

Guerrilla marketing therefore serves as a label for nontraditional communications between advertisers and audiences, which rely on an element of creativity or surprise in the intermediary itself. It is advertising through unexpected, often online, interpersonal, and outdoor avenues—unconventional, literally, in its choice of media platforms (i.e., engaging a medium beyond the traditional television commercial or newspaper advertisement). Guerrilla marketing’s resourceful license is remarkable not only in terms of content but equally that of context: expansively reconfiguring the space typically partitioned for commercial petition. Yet guerrilla marketing, as heir to an extensive proto-history, is not necessarily strictly “new” either but rather the latest outgrowth in an ongoing cycle of advertiser innovation.

A wide-ranging terminology has sprung up to characterize these techniques: ambient, astroturfing, branded content, buzz, graffadi, interactive, stealth, and viral, among others. They share a common allegiance to this organizing principle—the deployment of a space or channel that seeks to engineer engagement through a “cool sell” strategy. Guerrilla marketing is, therefore, a project of persuasion that cloaks itself casually and even invisibly to the consumer targets it courts in an attempt to orchestrate “discovery” of the commercial message as the constitutive experience; stated more abstractly, in Foucauldian terms, it is a mode of governance set upon an active subject, not a form of domination that has stereotypically defined the exercise of power.

To date, little research has analyzed how and why this form of marketing has grown as a means of reaching consumers, yet these tactics fit within a trajectory stretching back nearly a century, and this inquiry can be situated within and build upon related scholarly discussions at the intersection of advertising, audiences, governmentality, hegemony, public relations, new media, and the creative industries. Through a close examination of emblematic campaign examples, an archival analysis of trade discourse, and in-depth interviews with dozens of prominent practitioners, Your Ad Here peels back the curtain on a form of cultural production that reworks the conventional archetype of mass communication. It re-conceptualizes consumer governance through themes and practices of participation, populism, heterarchicality, decentralization, and freedom. At stake is no less than the structure by which the media environment is underwritten, the waning spaces in which one might avoid commercial entreaty, and the potential for devaluing, contaminating, or even burning out the “original institution[s]” hosting the new promotional forms.5

What these guerrilla strategies also suggest is that advertising might be evolving beyond certain basic organizing principles of the mass communication process, which have long defined it. Take, as one example, this classic definition: “Mass communications comprise the institutions and techniques by which specialized groups employ technological devices (press, radio, films, etc.) to disseminate symbolic content to large, heterogeneous and widely dispersed audiences.”6 Such a characterization tends to assume that the content is standardized, the context is delimited, and that messages start from a structural center and work their way to a social periphery. Above all, it seems to imply an obviousness— an intrinsic visibility—about the mass communication process, whether it be transmitting news, entertainment, or, indeed, advertising. Broad-casting long meant just that: a patent, top-down, one-to-many, centrifugal model of messaging.

If traditional advertising fit snugly within such a rubric, the challenges posed and opportunities raised by networked interactivity illuminate a different philosophy of consumer governance. In response, these guerrilla tactics demonstrate a decidedly more flexible, niche-seeking, and ambiguous bent, one more reflective of the aims and designs of public relations. Media and cultural studies—notably Stuart Hall’s theory of “decoding” reception and James Carey’s alternate emphasis on “ritual”—have long since challenged the primacy and simplicity of this transmission model, yet “the linear casual approach was what many wanted, and still do want, from communication research.”7 Advertisers might certainly be counted among this group, for much of their work has traditionally reflected an unspoken faith in linear causality, centralized dissemination, and unchanging content. Thanks to technology, at a juncture when once-firmly ascribed roles like sender and receiver are blurring and that content meaning is less stable and more spreadable than ever before—developments that media and cultural studies have long posited—advertisers might now more adeptly insinuate themselves into such dynamic processes.8

This flexibility points to an ongoing redefinition and reinvention of the industry overall. As but one outgrowth of this, awards shows have started crafting new categories to accommodate such originality with the medium itself. In 2004, the Clio Awards launched a new category called “Content and Contact” to honor “campaigns that are innovative in terms of the way they communicate . . . [and] because the most exciting leading agencies were focusing their efforts on projects that included creatives and also media strategists at the same time.”9 A year earlier, the Cannes Lions International Advertising Festival had inaugurated its “Titanium Lion” to honor work that “causes the industry to [stop in its tracks and] reconsider the way forward.”10 Two campaigns that have taken home this prize are analyzed in chapters 2 and 5: BMW’s The Hire and Burger King’s “Subservient Chicken.” On a smaller scale, the Lisbon Ad School inaugurated its Croquette Awards, the “first international guerrilla marketing festival,” in the summer of 2009.

More broadly, this media evolution comports with a larger post-Fordist shift in advanced capitalism. In recent decades, the Fordist assembly line—emblematic of large-scale, standardized mass production in the 20th century—has given way to more agile, unique, cost-effective industrial output: “The rigorously hierarchical chain of command of the Fordist system is rendered unnecessary by distributed information networks, while smaller, more autonomous work units compromising flexibly trained workers rather than Taylorized machine-tenders respond quickly and creatively and more in keeping with the new technologies themselves.”11

Much in the same way, guerrilla advertising like BzzAgent’s word-of-mouth seeding and MadMenYourself.com’s viral fodder represents a break from Madison Avenue’s classic, one-size-fits-all content, mass-produced and disseminated by centralized broadcasters in favor of smaller-scale flexibility more beholden to heterarchical patterns of information flow. That textual fluidity, being negotiable and improvised, bespeaks a recalculated approach to the exercise of producer power: working with the agency (and, as needed, the contested exchange) of autonomous networks, spaces, outputs, and “receivers.”

It is not broadcasting so much as the network that perhaps best represents “the core organizing principle of this [new] communicative environment;” the network being a model where agency is, fittingly, coded into structure.12 Guerrilla advertising strives to accommodate that evolving media ecology, coordinating and capitalizing on a more latent, many-to-many, centripetal model of participatory, contingent content distributed through social networks, be they online or off. If mass marketing was born of the need, meaning post–Industrial Revolution, to sell mass-produced goods, then the revolutionary forces calibrating this shift from push to pull media perhaps now require adaptively tailored interactions rather than monolithically Taylorized messages.

Thus, guerrilla marketing like that of word-of-mouth and its Web 2.0 equivalence depends upon a kind of promotional crowd-sourcing—one that is both enabled technologically (networked infrastructure makes it now more possible than ever) and advantageous culturally (for youth especially, because trickling up from the underground semiotically trumps fanning out through the mainstream). This collaboration burnishes an egalitarian image of “brand democratization,” a buzzword myth thought to be capable of equivocating any appearance of marketer power. Such a project, in turn, foregrounds “conviviality” rather than “transmission” as the “prevailing model of communication”—a move that suggests a different form and logic in ho...