![]()

1

DRIVING AMBITION

The Continuing Revolutions in Transportation

IN 1922 photographer Paul Strand began to take photographs of working parts of his motion picture camera and, fascinated, went on to photograph such other machines as drills and lathes, commenting on the beauty of their forms and workmanship and proclaiming them as one part of a new Trinity: “God the Machine, Materialistic Empiricism the Son, and Science the Holy Ghost.” For the United States the period 1920–1941 could not be described in classical terms as an age of such precious metals as gold, silver, or bronze. However, it was one in which much of American civilization owed its forms to the industrial metals steel and aluminum, and to the mineral oil. It was, indeed, an age of machinery: motor cars, airplanes, cameras, hydroelectric power, internal combustion engines, newspaper printing presses, electrical engines, radio, and yarns of artificial fibers.

In their Art and the Machine (1936) critics Sheldon and Martha Cheyney claimed how the “age of machine-implemented culture had begun.” In “The Americanization of Art” for a machine-age exhibition catalog of 1927, constructionist Louis Lozowick stressed how “The history of America is a history of stubborn and ceaseless effort to harness the forces of nature . . . of gigantic engineering feats and colossal mechanical construction.” Here was an inspiration for art, the raw material of industrial function, structure, and standardization that could be discerned in the “rigid geometry of the American city: in the verticals of its smoke stacks, in the parallels of its car tracks, the squareness of its streets, the cubes of its factories, the arcs of its bridges, the cylinders of its gas tanks.” Such mathematical order, indeed, organization, invited the “plastic structure” of art to capture the “flowing rhythm of modern America” in an idiomatic American art.

Plymouth automobile assembly line. By mass production, standardization, and interchangeable parts, Ford and other auto manufacturers brought motor cars within reach of their workers’ pockets, not only increasing the revolution in transportation but also preempting any claim of socialism that American capitalism divorced workers from the results of their labor. (Library of Congress).

Despite the dramatic economic profile of each decade—superficial prosperity in the 1920s, the agonies of the Great Depression in the 1930s, followed by the miracle of recovery and growth in 1940s—many Americans understood that this was a period with its different industrial and social strands drawn together by science and technology, with ever-faster communication and an ever more diverse range of consumer products. As historian Richard Guy Wilson explains in the 1986 catalog for the exhibition, The Machine Age in America 1918–1941, “The machine age meant actual machines such as giant turbines and new machine materials such as Bakelite, Formica, chrome, aluminum, and stainless steel. The machine age meant new processes—mass production, ‘Fordism’—factories, great corporations, and new ways of hiring. . . . The machine age encompassed the vast new skyscraper city, with its transportation systems compacted one on top of the other, and the new horizon city composed of filling stations, drive-ins, and superhighways.”

The ever-increasing number of new inventions had led to the creation of a new vocabulary to describe them. In 1888 a group of academics undertook to make a dictionary in ten volumes of all the words in English. The project was to last forty years. As they labored, the world moved ahead of them. Thus, in 1893, while they were still on letter A, appendicitis came into common use but too late for inclusion. When they got past letter C the cinema came into being and the lexicographers decided to include it among the Ks as kinema. Over 400 words beginning with C were also too late for inclusion. By the time the project was complete in April 1928 about one new word had entered the language for every old one. A supplementary volume was already necessary. Whereas in the nineteenth century there were only two colors of stocking—black and white—now there were forty-three. The 1929 edition of Webster’s International Dictionary found over 3,000 words had come into being in the period 1909–27. Of the 299 words beginning with letter A, 221 (two-thirds) were in the fields of science, medicine, and invention, and 82 of those were in aviation; 7 were in machinery. Only 1 was in art—atonality.

The heroes of America’s advanced, increasingly technological society were Henry Ford and Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr. In 1920 one car in two throughout the world was a Ford Tin Lizzie. Pioneer car manufacturer Henry Ford had transformed the society into which he was born through an astute combination of advanced technology and paternalist management. A more authentic folk hero than Ford was Charles Lindbergh, whose solo 33

-hour transatlantic flight from New York to Paris in May 1927 also combined new technical expertise with the traditional pioneer spirit. On his return New York brought down a storm of ticker tape to celebrate an achievement in which all Americans could take pride.

The Transportation Revolution of the 1920s and 1930s

Whatever the contribution to society of such men as Lindbergh, it was the automobile that shaped the new machine society and its culture most decisively. It was not only an agent of mobility but also a potent symbol of a new order. The scale of the continuing revolution in transportation achieved by cars between the world wars is suggested by the following statistics. In 1920 1,905,500 passenger cars were produced; in 1930, 2,787,400. In 1920 there were, altogether, 7.5 million cars on America’s roads; in 1930 26.5 million—or one car for every five Americans. In 1940 3,717,300 cars were sold in the United States. The rise in the number of miles traveled was equally dramatic—from 1921 with 55,027 miles per vehicle to 1930 with 206,320 miles per vehicle and then 1940 with 302,188 miles per vehicle. In the 1920s private intercity motor car traffic soon exceeded rail traffic and by 1930 it was six times greater. Very soon cars were not only a convenience but also a necessity for mind as well as body. When Sinclair Lewis came to satirize the small-town world of a middle-aged real estate man in Babbitt (1922), he observed, “To George F. Babbitt, as to most prosperous citizens of Zenith, his motor-car was poetry and tragedy, love and heroism. The office was his pirate ship but the car his perilous excursion ashore.” By the 1920s the automobile was automatically linked in most minds to the glamorous world of the happiness of pursuit created by advertising and to upward social mobility.

André Siegfried in America Comes of Age (1927) asserted how “it is quite common to find a working-class family in which the father has his own car, and the grown-up sons have one apiece as well.” The wife of an unemployed worker in Middletown told the Lynds, “I’ll never cut on gas! I’d go without a meal before I’d cut down on using the car.” In fact, less than half of blue-collar families owned automobiles. In his article, “Affluence for Whom?” for Labor History of Winter 1983, Keith Strieker concludes that there were probably 16.77 million cars for 36.10 million consumer units (families and individuals) and thus about 46 percent of the units had cars. An automobile was not a sign of affluence when a used car could be bought for $60 outright or for a deposit of $5 and delayed purchase by monthly instalments of $5. Of course, Americans were more likely to have cars than Europeans and the urban family probably had about a fifty-fifty chance of owning a car. Many automobiles belonged to companies; some families had more than one car; and many single people had cars. Some cars were scrapped during the year; some cars belonged to farms.

By the mid-1920s the automobile industry was dominant in the American economy and had made tributaries of such other American industries as petroleum (using 90 percent of petroleum products), rubber (using 80 percent), steel (20 percent), glass (75 percent), and machine tools (25 percent). Socially, the automobile increased opportunities for leisure and recreation, bridging town and country, affording escape and seclusion from small town morality, and generally shaping the view of an ever more mobile population to an urban perspective.

The Big Three: Ford, GM, and Chrysler

Just after World War I Henry Ford dominated automobile manufacture, both nationally and internationally, although on the domestic scene he would face increasingly serious competition from General Motors. In fact, the 1920s saw the full emergence of two other giant auto companies, General Motors (GM) and the Chrysler Corporation, to take their place at the side of Ford as the Big Three companies among automobile manufacturers.

New lamps for old. Shopworn Democratic standard-bearer William Jennings Bryan and Henry Ford, the mechanical genius whose name was synonymous with the new age of machines, in a publicity photo to promote Ford’s peace ship in 1915. Ironically, Ford came to detest many new values of the society he himself had done more to transform than any other individual and set about recreating a tribute to a bygone rural Arcadia in his Dearborn museum, while fundamentalist Bryan, who was usually taken as a symbol of bygone agrarian protest, became in the 1920s a front man for a Florida real estate company dedicated to creating an idyllic leisure retreat for the affluent. (Library of Congress).

Among other leading producers General Motors, founded in 1908 by William Durant, was originally intended to become a combine of other companies. As initially formed, it included the companies of Buick, Cadillac, Oldsmobile, and Oakland, and several lesser firms. By a series of rapid financial combinations, acquisitions, and mergers, Durant created a network of suppliers, assembly plants, and distributors. However, following an unexpected decline in sales, in 1910 Durant was forced out of General Motors. He then acquired Chevrolet and, supported by Pierre Du Pont and John Julius Raskob and the wealth of the Du Pont family, he recaptured control of General Motors in 1915. (The Du Ponts were an American family of French descent with a fortune originally based in textiles, chemicals, and explosives. Their concerns were incorporated in 1902 by Henry Algernon Du Pont. His three cousins, Thomas Colman, Alfred Irénée, and Pierre Samuel Du Pont, served as directors.)

By the end of World War I William C. Durant was planning construction of plants and facilities on such a vast scale that he required extra funds not only from the Du Ponts but also their British associates, the Nobels, and the House of Morgan. Indeed, it was only the outsize contribution of this powerful trio that saved General Motors from bankruptcy in the postwar recession. However, when William Durant tried to maintain the price of General Motors above its current market rate, he was forced to retire for the second, and last, time.

Henry Ford dealt with a postwar recession by cutting prices, insisting on rigorous economies throughout his company, and obliging suppliers and dealers to help him out; the suppliers by selling parts more cheaply, the dealers by accepting additional stocks that they could not sell immediately. Moreover, Ford attempted vertical integration, control of all processes from start to finish, acquiring raw materials and transportation to achieve an even flow from source to production to distribution. His aim was a giant and incessant conveyor belt for the universal car. Ford’s new plant on River Rouge became a prime example of modern, integrated production, in which Ford produced nearly all parts for the Model T and even made his own glass and steel. Although it was a superb achievement as technology and industrial integration, the Rouge plant was less successful as a business venture since it was inflexible and run on high fixed costs. The complex had been created to make a product that was already fifteen years old. Even minor changes could only be introduced at great expense. Ford’s difficulties arose not only out of his failure to recognize changing customer demands and their implications for marketing, but also the swift success with which General Motors managers exploited the new situation.

Pierre Du Pont replaced Durant as president of General Motors and began to reorganize the corporation’s administration and finances, and to revise its policies in production and marketing. Pierre Du Pont took his cue from Alfred P. Sloan, Jr., president of one of the firms acquired by Durant in 1916, and allowed such operating divisions as car, truck, parts, and accessories to retain their own autonomy. Thus the division managers continued to control their own production, marketing, purchasing, and engineering—as they had under Durant. However, what was new in the Du Pont-Sloan system was a new general office, comprising general executives and advisory staff specialists, to assure planning, coordination, and overall control.

First, Du Pont and Sloan (who then succeeded Du Pont as president in 1923) defined the roles of various executives in the general office and senior division managers in order to clarify authority and communications. Second, they arranged for the continuous collection and circulation of statistics to disclose the performances of the operating divisions and, indeed, the entire corporation. In time, much of this information and the decisions it inspired came to depend on market forecasts about production, costs, prices, and employment. It served as a yardstick for measuring performance.

General Motors led the way in improved mechanics and design. When automobile pioneer Charles K. Kettering became general manager of General Motors’ research laboratories (1925–1947), he directed research on improving diesel engines and the development of a nontoxic and noninflammable refrigerant. He also devised and conducted research into higher octane gasoline, adding tetraethyl lead. Cars became more comfortable; until the 1920s most new automobiles were open cars but by 1929 the great majority were closed models. In order to entice consumers, General Motors’ marketing included the development of an extensive range of models, an annual model, massive advertising, schemes to allow customers to trade in their old car in part payment for a new one, and regular and systematic analyses of the market. However, by using some of the same parts and supplies for their different models, General Motors hoped to retain one major advantage over the Ford system—economy of scale. Thus, between them, Pierre Du Pont and Alfred Sloan, by their rational innovations, boosted General Motors’ share of total sales from 12.7 percent of the market in 1921 to 43.9 percent in 1931 and 47.5 percent in 1940. General Motors created a new, decentralized form of management at the precise time that Henry Ford was ridiculing systematic management while drawing the threads of control of his own company more tightly into his own autocratic hands.

The Chrysler Corporation was formed out of the failing Maxwell Motor Company in 1925 by Walter P. Chrysler who introduced his own design of car, featuring a high compression engine. He also acquired the Dodge Brothers Manufacturing Company in 1928 and produced the Plymouth, a successful model that allowed Chrysler to compete with Ford and General Motors, thereby becoming one of the Big Three car manufacturers. In 1929 Chevrolet introduced the six-cylinder engine and set a pattern for future development wherein auto manufacturers concentrated on engineering improvements, suspension, engines, and overall design.

Thus the American automobile market was to be dominated by the Big Three producers. Independent manufacturers could only survive if they produced automobiles for a narrow, specialized market, such as motor cars for the affluent. However, in general they either declined, went out of business, or were absorbed by the Big Three.

Early automobiles were designed in the fashion of horse-drawn carriages and, as late as the 1920s, they continued the basic feature of clearly separated parts in their overall design. However, in the course of the 1920s manufacturers were made forcibly aware of the significance of body styling, especially after the introduction of closed cars, which increased their share of the market from 10 percent in 1919 to 85 percent in 1927. The most significant designer was Harley Earl of General Motors. Coming from a background of custom-body building in Los Angeles and, having specialized in creating unique designs for individual Hollywood film stars, Earl knew how to create the widest range in styles from the same essential design and to provide even greater sophistication by subtle changes in body, attachments, and color within different price ranges. By 1928 designer Norman Bel Geddes refined the conventional angular design of cars into a rounder, more harmonious form in a design that was never put into production by manufacturer Graham Page but which influenced others’ work.

Walter P. Chrysler had his top engineers, Fred Zeder, Owen Skelton, George McCain, and Barl Breer, and outside designers William Earnshaw and H. V. Hendersson, produce a streamlined automobile, the Airflow, for 1934 and in successive years. It had a torpedo-like body, bullet-shaped headlamps, slanted windshields, and curved window covers. The overall shape was a parabolic curve, like the then fashionable teardrop. However, such striking changes in the front of the vehicle were less significant than Chrysler’s visible alterations to the body, with the engine placed farther forward and lower between the two front wheels—rather than in its usual position behind the front axle—and a lower frame seating passengers between front and rear axle, and all in a steel body welded to a steel frame. The interiors used chrome tubing for the seats and marbled rubber for the floor. Here was one of the most beautiful of all designs of the machine age, complete with a long, low-slung look decorated with a triad of horizontal speed lines to accentuate the car’s purpose.

Cars conveyed more than their passengers. They could carry packages containing alcohol and did so in the period of national prohibition of alcohol. They certainly carried change—the conventions of the countryside were challenged by those of the city. They provided means and opportunity for sexual freedom impossible in a static society. In the Lynds’ study Middletown one judge referred to the car as “a house of prostitution on wheels.” Because they were used so much by bootleggers and gangsters, automobiles were never dissociated from criminal activities in the public mind. “Don’t shoot, I’m not a bootlegger,” was the caption popular among car owners in Michigan, and prohibited there by the attorney general in 1929. Whereas at the beginning of the 1920s automobiles represented an alternative to alcohol, at its end they symbolized booze and beer running and everything that was subversive of national prohibition of alcohol. In addition, they provided an unfortunate comparison with liquor: how a potentially lethal invention could be controlled and made comparatively safe.

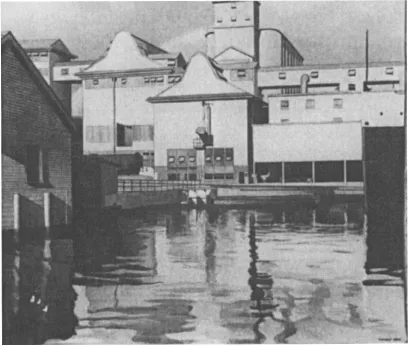

Charles Sheeler,

River Rouge Plant, (1932), 20″ × 24

″. (Photo by Geoffrey Clements; Collection of Whitney Museum of American Art, New York). In 1927 the Ford Motor Company commissioned precisionist artist Charles Sheeler to take a series of photographs of its River Rouge Plant, the first factory capable of manufac...