eBook - ePub

Out of Work

Unemployment and Government in Twentieth-Century America

- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Out of Work

Unemployment and Government in Twentieth-Century America

About this book

Argues the cause of unemployment may be the government itself

Redefining the way we think about unemployment in America today, Out of Work offers devastating evidence that the major cause of high unemployment in the United States is the government itself.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Out of Work by Richard K Vedder,Lowell E. Gallaway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Regierung & Wirtschaft. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Unemployment Century

Of the five centuries during which the United States has been settled by Europeans, in only one, the twentieth century, has unemployment been a dominant political and economic issue. Whereas in nineteenth-century America passions erupted over inflation and deflation, tariffs and taxes, slavery, the disposition of public lands, central banking, and the regulation of monopolies, public debate about the “unemployment problem” was sporadic and localized. Indeed, the word “unemployment” did not even exist during most of the century, and when Alfred Marshall wrote the definitive nineteenth-century treatise on economics in 1890, he mentioned the word on but one page.1

By contrast, unemployment became the dominant economic issue of the twentieth century both within the academy and in the realm of public policy. During the 1890’s, there were but two articles dealing with the issue in serious journals of economics and statistics; by the 1930s, scores of papers were published discussing the measurement, determinants, and effects of unemployment.2 While in the last presidential election of the nineteenth century, that of 1896, the central economic issue was monetary policy and the gold standard, by 1932 unemployment had moved center stage.

Rising public concern over unemployment led to political pressure to “do something” about the unemployment problem. Even in the first decade of the new century, the unemployment arising out of the panic of 1907 led to cries to eliminate the root cause of financial instability. This, in turn, ultimately led to the Federal Reserve Act, the first major federal involvement in macroeconomic intervention. A few years later, during the 1920–22 economic downturn, a presidential commission on unemployment was created.

In the 1930s, a revolutionary activist approach to the unemployment problem was implemented as part of the New Deal. No longer was the government simply content to try to eliminate monetary instability or study the causes of unemployment. New legislation involved the government in labor markets in important new ways. Even before the New Deal, the Davis-Bacon Act got the federal government into the business of setting wage levels. The National Industrial Recovery Act, the Wagner Act, the Fair Labor Standards Act, and legislation creating the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration are but a few examples of the burst of new federal government initiatives designed to bring about “relief, recovery, and reform”—and lower unemployment—during the New Deal.

The crowning manifestation of government activism was the Employment Act of 1946, which declared the eradication of unemployment a national priority. Public-policy efforts to end unemployment did not end with the Employment Act. Activism peaked in the 1960s and 1970s. Not only was further legislation passed emphasizing the importance of full employment as a national goal (e.g., the Humphrey-Hawkins Act), but numerous new institutions were created as an outgrowth of the War on Poverty (e.g., the Jobs Corps and the Office of Economic Opportunity). To deal with persistent unemployment, a variety of new public-assistance programs, such as Medicaid and food stamps, were created. While the Reagan era of the 1980s brought a stifling of new unemployment initiatives, little was done to dismantle the apparatus of federal programs, and the activist monetary and fiscal policies, that had been created over the previous decades. Just as earlier Republican presidents Eisenhower and Nixon had not attempted to dismantle the New Deal and the Great Society, so President Reagan, by far the most conservative modern American president, did relatively little to undo the “safety net.” The legacy of macropolicy expansionism established in the New Deal era was left largely intact.

While interest in the unemployment problem tended to rise and fall with the business cycle, concern was not exclusively directed to cyclically related unemployment. Thus in the prosperous 1920s, there was mounting concern about technological unemployment. Likewise, the concept of what we now term “frictional unemployment” was developed.3 Similarly, in the equally prosperous 1960s, structural unemployment was a concern—the mismatch of skills of those unemployed with the skills needed for jobs available.

In the 1970s, economists coined a term to refer to the noncyclical forms of unemployment: “the natural rate of unemployment.” Much of the modern discussion about employment is related to the natural rate of unemployment and its determinants. Thus the twentieth-century discussion of the unemployment problem is partly a by-product of concerns over economic fluctuations, but also in part of concern over idleness that reflects other noncyclical factors.

Why the rise in interest in unemployment? To a large extent, the issue grew in importance with the urbanization of America. Before the Civil War, most Americans were engaged in farming. Most farmers, in turn, were either self-employed, or slaves who could not become unemployed almost by definition. After 1890 or 1900, cheap or free public land in the West was no longer readily available, and the proportion of Americans working for wages had grown strikingly with industrialization and urbanization. In the nineteenth century, the urbanized proportion of the American population rose from 6 to 40 percent of the total, and it became a majority by 1920.4 Whereas no more than 5 percent of the labor force was engaged in manufacturing in 1800, by 1920 that proportion approached one-third.

The decline in the relative importance of self-employed individuals increased the vulnerability of workers to unemployment, and as a consequence the incidence of involuntary joblessness rose with the passage of time. Although good annual data are unavailable for almost all of the nineteenth century, it is unlikely that the nation suffered from a double-digit unemployment rate, at least on any sustained basis, until the 1890s. It was the Great Depression of the 1930s, however, with a full decade of double-digit unemployment, that led to the overwhelming preoccupation with the unemployment question.

Unemployment increasingly evoked both intense humanitarian concerns over the plight of individuals and broader concerns over the efficiency and effectiveness of the aggregate economy. Workers who lost their jobs “through no fault of their own” often found themselves with a dramatic drop in income and increasing financial pressures. They suffered dramatically, both economically, and also psychologically, as their self-esteem declined with each day of idleness. Nationally, the loss of 10 or more percent of the most productive resource meant a decline in total output, and a reduction in capital formation needed to augment longer-term increases in material well-being.

Variations in Unemployment over Time

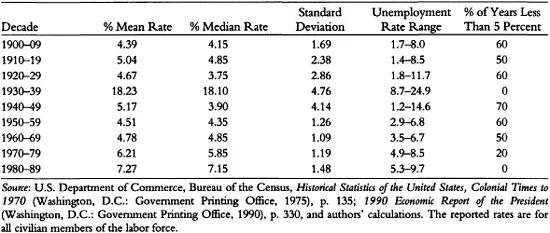

The problem of unemployment was not merely that it was growing dramatically in size over time, but that its magnitude varied significantly over time and space, often striking individuals unexpectedly before they could prepare for it. Over the first nine decades of the twentieth century, the official annual unemployment rate averaged 6.6 percent, but varied between 1.2 percent and 24.9 percent.5 Even if one looks at decade averages of unemployment (see table 1.1), the variation in rates is still huge. The 1930s stands out as an extraordinary aberration—mean unemployment rates well over double the next highest unemployment decade (the 1980s). Yet even the 1980s witnessed a mean decade unemployment rate over 50 percent higher than in four other decades (the 1900s, 1920s, 1950s, and 1960s.)

TABLE 1.1

VARIATIONS IN UNEMPLOYMENT IN THE U.S., BY DECADES, 1900–1990

VARIATIONS IN UNEMPLOYMENT IN THE U.S., BY DECADES, 1900–1990

The bad news from table 1.1 is that the lowest mean unemployment rates tended to come early or in the middle of the century: the mean unemployment rate rose steadily by decade after the 1950s, and even the 1950s figure was higher than observed in the very first decade of the century. Whereas unemployment rates of 5 percent or less tended to be the rule rather than the exception in the period 1900–29 and also in the era from 1940 to 1969, by the 1980s unemployment rates that low simply did not occur.

The good news from table 1.1 is that the absolute variation around the mean or median unemployment rate was lower in the last half of the century than in the first half, reaching a nadir in the 1960s, when the highest unemployment rate for the decade was a mere 3.2 points above the lowest rate, and the standard deviation barely exceeded one. The good news with respect to unemployment variation is tempered, however, by the fact that moderate increases in fluctuations were observed after the 1960s.

Moreover, the official data for the first decades of the century were constructed from decennial census “benchmark” data, and are thus subject to considerable error. Christina Romer has made a compelling case that the variation in unemployment in the early decades of the twentieth century was much less than the official numbers indicate, and that the postwar unemployment instability is understated, suggesting that the observed reduction in unemployment instability shown in table 1.1 is in fact in large part a statistical artifact.6

It is tempting to try to draw broad-brush conclusions about trends in unemployment by comparing data for various subperiods in the twentieth century. The conclusion one reaches, however, is highly sensitive to the periods chosen. If one arbitrarily divides the ninety years of available data in half, the evidence shows that the mean unemployment rate in the first half, 1900–44 (7.9 percent), is considerably higher than in the last half, 1945–89 (5.49 percent). Moreover, unemployment variation (as measured by the standard deviation), is dramatically lower in the latter period. On the basis of this evidence, the inclination is to accept the conventional wisdom that the unemployment record has been clearly superior in the period of governmental activism that followed the Employment Act of 1946.

Yet one could just as rationally divide the twentieth century into three equal periods of thirty years each: 1900–29, 1930–59, and 1960–89. The first period is an era of very limited direct governmental involvement impacting on unemployment, the middle period is a transitional era where an interventionist policy came to be increasingly accepted, and the latter period is one of consistent governmental activism in the economy, albeit with increased skepticism about its effectiveness as the period unfolded.

The mean unemployment rate of 4.7 percent in the first (nonintervention) period was far lower than the 6.09 percent rate observed from 1960 to 1989, or the 9.3 percent average rate in the transitional era of 1930–59. While unemployment variation was somewhat lower in the 1960–89 period than in the early decades (standard deviation of 1.60 versus 2.29), Romer’s insight suggests that this almost entirely reflects faulty data rather than a real phenomenon. Using this tripartite division, the evidence generally points to the conclusion that the unemployment situation was better in the relatively laissez-faire era before the Great Depression than in periods since.

Spatial Variations in Unemployment

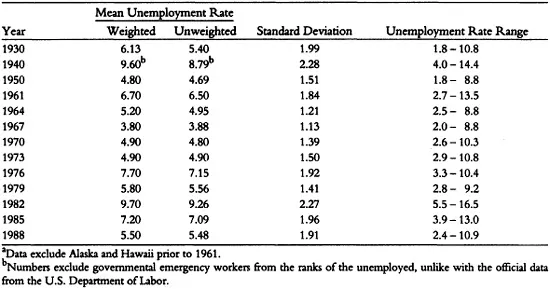

In addition to substantial intertemporal variations in unemployment, interstate differentials in joblessness have been great throughout the period. Before 1960, good state unemployment data were not collected on an annual basis, although information was gathered as part of several of the decennial population censuses.7 In table 1.2, indicators of interstate variation in unemployment are presented for a number of years.

TABLE 1.2

INTERSTATE VARIATIONS IN UNEMPLOYMENT, VARIOUS YEARS, 1930–88a

INTERSTATE VARIATIONS IN UNEMPLOYMENT, VARIOUS YEARS, 1930–88a

Note that throughout the period for which data are available, there are areas of the United States where the incidence of unemployment is three to four times that of other areas. Typically in recent years, there are states in which the unemployment rate is 10 percent or more, and other states where the rate is about 3 percent.

Do unemployment differentials between states tend to persist over time? The evidence suggests that in the very long run, there is no correlation between unemployment rates for different time periods. States that in one time period had high unemployment rates did not have a clear tendency to have relatively high rates in the later period. For example, the correlation between the unemployment rates for the forty-eight contiguous states and the District of Columbia in 1930 and 1988 is actually negative (-.13). Yet the “very long run” is actually quite long—perhaps forty or fifty years. There are relatively long periods in twentieth-century American history where unemployment variations have seemed to persist in something of a pattern. For example, the correlation between unemployment in 1961 and in 1988 for the forty-eight contiguous states and the District of Columbia is a fairly high. 47. Between 1930 and 1950 it was even greater, .62.

Some states seem to have persistently high or low rates of unemployment. For example, for twelve of the thirteen years examined from 1930 through 1988, the unemployment rate in West Virginia exceeded or equaled the national average. By contrast, in every single year the unemployment rate in Nebraska and South Dakota was less than the national average. Thus it is clearly possible that there are some regional variations in the normal or natural rate of unemployment.

Demographic Variations in Unemployment

It is a well-established fact that in the late twentieth century unemployment rates tended to be dramatically higher for nonwhite than for white workers, and that younger workers have a much higher incidence of unemployment than is true among older persons in the labor force. On the other hand, gender differences in the incidence of unemployment are relatively small. Have these patterns persisted throughout the twentieth century?

RACIAL DIFFERENCES

The answer to that question,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- Foreword by Martin Bronfenbrenner

- Preface to the Updated Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- 1 The Unemployment Century

- 2 Unemployment in Theory

- 3 The Neoclassical/Austrian Approach: An Overview

- 4 The Gilded Age

- 5 From New Era to New Deal

- 6 The Banking Crisis and the Labor Market

- 7 The New Deal

- 8 The Impossible Dream Come True

- 9 The Gentle Time

- 10 The Camelot Years

- 11 “Pride Goeth Before a Fall”

- 12 The Winds of Change

- 13 The Natural Rate of Unemployment

- 14 Who Bears the Burden of Unemployment?

- 15 Unemployment and the State

- 16 Afterword

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Authors