![]()

1

Migration and the City

The New York City Department of Health conducted its first citywide health survey in 1915. The racially segregated African American and British West Indian section of Columbus Hill, an impoverished midtown Manhattan neighborhood, had exhibited inordinately high rates of infant and maternal mortality. The Department of Health termed it a “sore spot” in its 1916 report, a place warranting immediate help.1

So, beginning in 1917, with powers devolved from the Department of Health, the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor (AICP) coordinated public and private efforts to stem the tide of black infant and maternal deaths within this area, targeting syphilis among black women and congenital syphilis among their young as the culprits. All the while, the Department of Health and the AICP closely monitored and measured the progress and results of their Columbus Hill work because they wanted to further test their methods and hypotheses in an additional area: one they believed was purer, more racially distinct. To meet this need, in 1918, they selected Lower Manhattan’s “Little Italy,” or the Mulberry District—even though the neighborhood’s infant and maternal mortality rates were vastly eclipsed by other “sore spots,” areas with health problems nearly as problematic as those of Columbus Hill. Nevertheless, the AICP focused on tuberculosis-related morbidity and mortality among childbearing Southern Italian women, and pneumonia and enteritis among their infants.

Mothers and children in both neighborhoods received modern, cutting-edge health care—at the time, New York City stood at the apex of maternal care in the United States—but the care they received was often shrouded in racially gendered and classed misconceptions and stereotypes of their supposed inferiority. Health care efforts in both neighborhoods were framed and hampered by issues of race and fractured by conflicts between mothers and health care workers over “correct” and “modern” birthing and child-rearing methods. In addition, when pressured to show that its methods worked, the AICP produced pamphlets that it distributed among the public health and medical communities. These reflected the biases and positions of the agency, even as it labored to improve the health of women and children. Physicians who treated Columbus Hill’s black women and children for syphilis may have used their clients to further their own research agendas. And in the Southern Italian Mulberry District, where the AICP was surprised by maternal resistance to its prenatal work, it may have “encouraged” its results when the publication of its infant and maternal health work is compared to internal documents.

Years of health demonstrations—experimentations—in both areas passed, and, despite its racialized foundations and questions regarding the efficacy of its programs and validity of its data, the AICP coordinated and oversaw modern infant and maternal health care for black and Southern Italian women. These initial programs—their purpose, structure, and outcomes—and how the African American, British West Indian, and Southern Italian female clientele of Columbus Hill and the Mulberry District responded, are the basis of this book. Officials and the general populace alike targeted poor migrating populations as carriers of contagions; more narrowly, they targeted impoverished migrating women as potential carriers of contagions, through their bodies and the bodies of their unborn children. Seeing them as more than bearers of disease—seeing the cultural and social systems of identity and agency that they bore—means analyzing migration historiographies created by scholars as well as creatively mining other nontraditional methods of cultural and social transmission—stories, plays, and poetry. All are equally important in creating a comparative study of African American, British West Indian, and southern Italian women’s responses to infant and maternal health care—basically, creating multiple client-based studies that never before existed.

But for now: Who were the women of Columbus Hill and the Mulberry District? Where did they come from, why did they migrate, and what cultural and social systems of identity and agency did they bring to New York City?

Immigration and Migration History and Historiography

Migration scholars have traditionally conceptualized the reasons behind group movement from one land to another in terms of “push and pull”; in other words, concretized and/or ideological agents (better jobs; the notion of freedom) pulled persons to a perceived, hoped-for better land, while other concrete and/or ideological agents (poverty and the lack of jobs; oppression from those in domination) pushed populations from their homelands. In the case of migration into the United States, primary emphases on the modes and types of migrations have also been bounded by historical era and origin. Many migrationists, with a culturalist perspective, accept the premise that this is a “land of immigrants” without questioning what “immigrant” means and, even more significant, without a recognition of the native populations who inhabited (and whose descendants still inhabit) the land. These “First Peoples” do not fit into the “immigrant” trope, nor does their forced or willing movement within the Americas. Furthermore, the tens of millions of West and Central Africans, also trans-Atlantic migrants, who came to the Americas by force, or whose descendants have moved forcibly or willingly throughout the Americas, have been considered outside the pale of trans-Atlantic (read: European) migration history. Often, these disparate but linked groups of peoples brushed elbows on a daily basis, intermarried and had children, competed for jobs and housing, were used to define how they and other groups would be conceptualized within the social, cultural, and legal fabric of the country, and how the United States conceived of itself and how it also would (and should) be reconceived as a land containing heterogeneous immigrants within its own seemingly homogeneous, collective identity.2

To criticize the creation of subfields in history at large, and in immigration and migration history in general, is not my purpose here: to refresh, challenge, or even subvert the telling of history by questioning, rethinking, and reworking popularly accepted notions of the past is part and parcel of how humans create history. Often, the perspectives and voices of the subordinated and disenfranchised provide a more nuanced depiction of an era than those who fear dragging out any other perspectives and voices that would question accepted narratives of the status quo. I am purposefully questioning the status quo by asking why the immigrations and migrations of those of African descent are still kept outside the boundaries of trans-Atlantic European migration history, particularly when the movements occurred simultaneously, often to the same areas and, while seeming different on the surface, often occurring for similar reasons. For a time, racial difference needed to flex its muscles to demand its place in the sun of migration scholarship. Gendered perspectives on migration have had to perform the same task.

Currently, however, a major flaw that continues in migration history has been the continued separation of so-called racial groups as if their perceived identities have made their movements—and reasons for moving—different, to the point of conflating differences of histories as salient divisions to justify differences of scholarship. As Russell Menard has stated, both the American colonies and the United States resulted from outer migrations, usually conceptualized as European and heterogeneous in origin. America’s imagined homogeneity was thus achieved not by constructing a cross-cultural and transnational identity based upon “Old World Origins” but upon race, since the “‘re-peopling’ of North America . . . resulted in a holocaust for the Indians and in slavery for the transported Africans.”3 Simultaneous events with different origins and reasons, but simultaneous outcomes: after the creation of the new republic, membership for aliens became racialized because, always at the bottom, were “inferior” groups who, even if indigenous to the land or having had several generations born on the land, were not recognized as citizenship material. In fact, migrating Europeans, whether apprised of the situation in the United States beforehand or not, were usually the only group to hold the “whiteness” key to naturalization between 1790 and the 1870s.4 It is for this reason that Menard advocates the inclusion of the migrations of African peoples in the literature of normally European trans-Atlantic migration history, which has been stifled by a “profound Eurocentrism” in the past.5

Therefore, the effect of separating group migrations by race, while necessary at times and enlightening in monographs, has created scholarship based upon separate “racialized” and also “gendered” and “classed” group differences. To look at comparative migrations at their fullest, I will examine the movement of African Americans, Southern Italians, and British West Indians to New York City from 1880 to 1930s in relation to one another and, later, in relation to their interactions with the New York City public health care and medical systems.

African Americans and British West Indians in Columbus Hill

What type of environment did African Americans and British West Indians encounter upon arriving in New York City? In the case of Columbus Hill, blacks encountered a community unique in its incongruities of ethnic diversity and racial segregation, picturesque surroundings and intense poverty, and a “cultured” past buried in a discordant, tenuous present. In short, Columbus Hill both enervated and exasperated. Its inhabitants were a diverse mixture of native- and foreign-born blacks, native-born whites, and Irish, Jewish, and Italian immigrants.6 The earlier race riots that occurred between blacks and whites when the area had been known as San Juan Hill were but a distant memory by the 1915 census.7 Unfortunately, the détente merely reinforced Northern de facto segregation: by 1922, the bulk of Columbus Hill’s black community resided on West 61st Street, where 1,641 people lived in two and a half acres of squalid tenements.8

Columbus Hill proper was an elevated area that covered fifty-five city blocks and extended northward from 54th Street to the south, 70th Street to the north, and between Central Park West and Eighth Avenue on the east to the Hudson River on the west. While the total neighborhood reflected its multinational basis, most of the area’s native-born blacks and those from the West Indies lived segregated lives, crammed into tenements on 61st through 63rd Streets, from Amsterdam Avenue to the Hudson River.9

| table 1.1. Population by Race, 1910 and 1920 |

| Columbus Hill and vicinity | | Areas 147 and 151 |

| Racial group | 1910 | 1920 | | 1910 | 1920 |

| Native whites | 13,150 | 14,383 | | 873 | 1,065 |

| Whites (foreign descent) | 20,991 | 19,857 | | 2,442 | 1,773 |

| Foreign-born whites | 19,169 | 18,115 | | 2,222 | 1,348 |

| Negroes* | 9,825 | 8,180 | | 7,291 | 6,248 |

| Other colored | 113 | 175 | | 23 | 5 |

| Total | 63,248 | 60,170 | | 12,851 | 10,471 |

| * The black population of Columbus Hill proper (Sanitary Areas 147 and 151) was 15.5 percent of the total Columbus Hill population in 1910, and 13.5 percent in 1920. Part of Sanitary Area 147 (created in 1920) corresponds to Areas 113 and 115 (created in 1915); Area 151 (created in 1920) corresponds with Area 119 (created in 1915). Also, the black population in the area had increased to 8,928 in 1922. Data are taken from Holmes, “Sociological Survey,” 2. |

Referred to by one social worker as the “first stopping place for the newcomers from the British West Indies, the Virgin Islands, and the Southern [United] States,” Columbus Hill’s black community included newly arrived persons from various Central and South American countries as well.10 As primarily native-born American rural and urban migrants and nonnative immigrants to the largest urban center in the nation, Columbus Hill’s black men and women constituted a marginalized workforce, exploited by employers who placed a higher value on southern and eastern European migrant labor.

Despite the neighborhood’s poverty, the areas outside of Columbus Hill’s boundaries possessed an urban ambience. The urban wonders of Central Part and the Hudson River—one manmade and the other natural—created an atmosphere that provided its citizens with those “periods of refreshment” so immensely important to an area heavily congested with tenements and businesses. The neighborhood was also steeped in early New York City history. Columbus Hill was part of what had been the Bloomingdale (from the Dutch Bloemendael, or “vale of flowers”) section of Dutch Manhattan in the seventeenth century. DeWitt Clinton Park now occupied the area that had been the eighteenth-century homes of General Garrit Hopper Stryker and the Mott family, and the Bloomingdale Academy, first opened in 1815, was located at West 74th Street.11

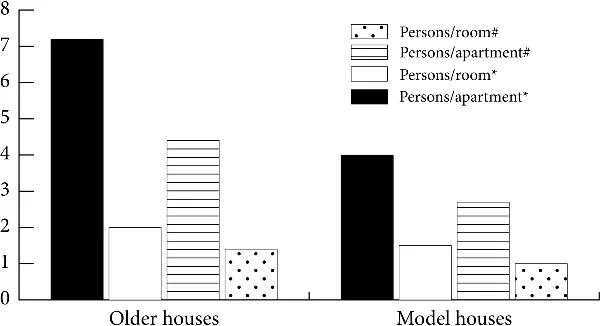

By the 1910s, Columbus Hill underwent rapid changes, shifting from a heavily residential district to a business area. Newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst and Arthur Brisbane, another wealthy New Yorker, owned the lion’s share of residential and business properties in the district.12 Blacks owned few residences. The housing situation was deplorable. Overcrowding became the primary problem in older tenements and houses: 7.2 people per apartment on average resided in dilapidated, pre-1901 dwellings (see figure 1.1). Older housing was cheaper than the new model apartments (on average, the rents for older apartments were $1.20 per week, versus $1.85 in modernized tenement “homes”), yet the differences were financially and aesthetically significant.13

Although they were few, model apartments such as the “513 desirable apartments” called the Phipps Houses and the City and Suburban Homes were located on 62nd, 63rd, and 64th Streets, just north of Columbus Hill’s heavily black 61st Street. Built after 1901 and constructed to comply with New York City’s newer housing laws, they possessed considerably more frontage space than older tenements (approximately 45′6″, compared to the general 25′ of older houses) and were built with interior courts and fireproof halls. Out of one hundred model apartments randomly sampled in Norman Holmes’s “Sociological Study” of Columbus Hill, each had at least its own private toilet, and eleven four-room apartments had full baths. Understandably, in a city where poverty and poor housing had more than a casual acquaintance, the waiting list was long for such dwellings. If one were lucky enough to afford and procure a model apartment, the aesthetic and social benefits were tremendous.

“Too much cannot be said of the benefits of good housing in a colored neighborhood,” declared social activist Mary White Ovington, the only white resident of the model Phipps House apartments on 63rd Street. “Church[es] and philanthropy had done and are doing excellent work on these blocks, but a sudden and marked improvement came from good housing, from the building of clean, healthful homes for law-abiding people.”14

Those who could not afford newer housing suffered in every sense. Only 732 of Columbus Hill’s older apartments, or 21 percent of its total residences, were considered “passable,” and Lincoln House’s social workers argued that although some h...