![]()

PART I

In the Basement

The Church as a Battleground

![]()

1

“Garibaldi and His Hordes”

Giuseppe Garibaldi would not be the last Italian to learn after arrival in New York that he had to reckon with the power of the Irish.

The future Italian liberator came to the city in the summer of 1850 at the low point in his struggle, fleeing a disastrous military defeat in Rome. Italian nationalists had taken the city from Pope Pius IX, only to lose it again. Garibaldi had fought valiantly on the barricades to hold the city for the nationalists, then fled when it fell as forces from France and Austria rallied to the pope’s aid. While evading the Austrian army in a series of hairbreadth escapes, he lost his wife, Anita, to illness. Hurting both emotionally and physically, he was unable to move his right arm because of severe rheumatism that worsened during his thirty-three-day passage from Liverpool.

Still, he was “the world renowned Garibaldi,” a man who “will be welcomed by those who know him as becomes his chivalrous character and his services in behalf of Liberty,” as the New York Tribune put it. Many New Yorkers were eager to greet him as a hero for his fight against Old World despots.

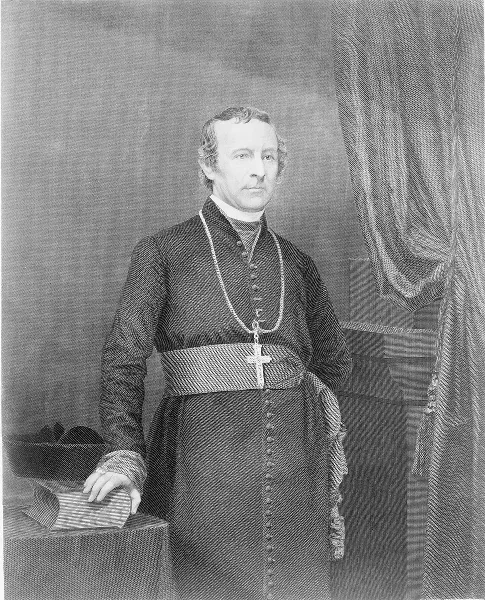

Even so, the New York Herald warned, Garibaldi was likely to incur the wrath of Bishop John Hughes, the tough-minded chieftain of the rapidly growing Irish Catholic population, when he arrived. The city’s Common Council showed no interest in welcoming Garibaldi. The Herald averred that since the Italian revolutionaries had dared to oppose the pope, “the petty politicians, fearing the influence of Bishop Hughes, are silent about their efforts in the cause of freedom.”1

Were it not for attacks on the pope, it might be expected that a man like John Hughes would have had a soft spot for Garibaldi and his liberation movement. Having grown up in County Tyrone with the legacy of British penal laws, he knew what it was to live under oppressive foreign domination. Those laws resulted in a massive transfer of land and wealth from Irish Catholics to Protestants in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with Catholics barred from acquiring property unless they converted. The rural Irish became tenant farmers, with tiny plots of land and without access to the common grazing pastures they had traditionally used. British landlords profited by selling Irish-grown food to industrializing England. Against that background, the disastrous potato crop failure that began in 1845 turned into a massive, history-transforming catastrophe. By 1851, the Irish population had dropped by about two million. More than a million died of starvation and related diseases, and many more people migrated. The population continued to dwindle for decades. One consequence of the Great Famine was that New York turned increasingly into an Irish Catholic city, despite its powerful anti-Catholic undercurrent. In New York, as in the nearby city of Brooklyn, a quarter of the population was Irish by 1860. Hughes was their leader, and he never forgot the long suffering of the Irish or their humiliation at Protestant hands.2

A well-built former day laborer who spoke without the brogue of his native land, Hughes took part in a New York fundraiser for a planned insurrection in Ireland in 1848, ruefully aware that encouraging warfare clashed with his role as a bishop. “My contribution shall be for a shield, not a sword; but you can contribute for what you choose,” he said as he donated five hundred dollars. He was embarrassed when the rebellion quickly failed.3

While Hughes was not shy about supporting rebels in Ireland, he condemned the Italian revolt for its attack on the pope. The publisher Horace Greeley, present when Hughes put down his money for the Irish rebellion, needled him for opposing Italian freedom. But to Hughes, an attack on the pope was an attack on the Catholic faith.

So he swung into action, assailing the “sacrilegious invaders” who had dared to drive the pope from Rome. “They wield the stiletto, and sacrifice by assassination the human victims who are to propitiate the goddess of Young Liberty in Italy,” Hughes wrote, accusing Greeley of overlooking Italian atrocities against the church.4

In a follow-up letter published in the New York Courier and Enquirer, Hughes attacked one of the city’s most prominent Italians, G. F. Secchi di Casali, who had come to New York from Piacenza in northern Italy six years earlier and founded the newspaper L’Eco d’Italia, or Echo of Italy, in 1849 to support the Italian cause. The bishop noted that Secchi di Casali “had volunteered his able pen to sustain Mr. Greeley’s view of Italian affairs.” He continued,

Mr. Casali is an Italian, and professes to be a Catholic, although the spirit of a decided enemy to Catholic faith breathes through all I have seen from his pen . . . he is mistaken, if he supposes that American Protestants will respect him the more for the infidel sneers which he utters against the Catholic religion, while he has not the Saxon candor and moral courage to disavow the outward profession of it.

Hughes also assailed a small group of Irish Catholic New Yorkers who planned to meet with the aim of raising funds for the Italian revolution. “I have a pretty good idea of what description of Irish Catholics will compose such a meeting—Irish Catholics à la New York Nation, who imagine themselves patriotic simply because they are not religious,” he wrote in the same letter.5 The New York Freeman’s Journal, a paper Hughes started and then sold in 1848 to the aggressively outspoken Episcopalian convert James McMaster, carried on the fight. It denounced the Italians as false patriots, reckless killers, and political quacks.

And so the line of battle was set. From Hughes’s point of view, even a great freedom fighter like Giuseppe Garibaldi was on the wrong side of the barricades. The deepest political aspirations of the Irish and the Italians conflicted—they were tied up in diametrically opposed views of the pope. For Italians who dreamed of freeing their native land from the dominance of hated foreign powers such as Austria, the Catholic Church was an obstacle. Pope Pius, after initially raising the nationalists’ hopes that he would support their cause, seemed to retreat into the hurtful past when he continued the Vatican’s alliances with foreign royalty. Italian nationalists treated this as a betrayal, and realized that to achieve their goals, they had to conquer Rome itself and the surrounding papal states. This meant going to war against the pope and the armies of his formidable allies in Austria, Spain, and France.

At the same time, for the Irish who dreamed of freeing their island from centuries of unjust British rule, Catholicism was fused with national identity. The Catholic Irish had clung to the faith of their fathers even when the crown had tried to subjugate them by outlawing the practice of “popery.”6 And then came the Great Famine, changing the course of Irish history in many ways. One result, beyond prompting a massive migration that filled lower Manhattan with a ragged, impoverished people, was that the Irish would hold ever more fervently to their faith. Defending it meant everything. In 1850 the typical Irish Catholic in New York would be unlikely to know an Italian, since there were so few in the city. But anyone who read a newspaper would know that the Italians had gone to war with the pope, a fact that would color the Irish Catholic view of the Italians in New York from the very beginnings of their relationship.

***

There were just 853 Italians living in New York in 1850, while more than a quarter of the city’s population of 515,547 was Irish. (Census data don’t distinguish between Protestant and Catholic Irish.)7 From its small numbers, the Italian community produced a committee of prominent men to welcome Garibaldi, including Felice Foresti, a white-haired professor of Italian literature at Columbia College whom the Austrians had imprisoned for eighteen years; General Giuseppe Avezzana, who had defended Rome with Garibaldi; and the inventor Anthony Meucci, who is often credited with having invented the telephone ahead of Alexander Graham Bell.

Reporters scrutinized the hero: “Garibaldi is not so ferocious in appearance as some engravings have represented him to be; he has fair hair, and a red beard,” the Herald remarked. “He is of middle stature, and of pleasant countenance, with eagle eyes.”

The newspapers heralded plans for Mayor Caleb Woodhull to receive Garibaldi at the Astor House, a leading hotel on lower Broadway. French and German socialists jumped in with their own plans for a parade. But Garibaldi wanted so much to avoid a fuss that when he cleared quarantine on Staten Island on August 4, 1850, he didn’t alert anyone. Finding refuge north of the city in Hastings-on-Hudson, he wrote a letter on August 7 in which he begged off from the planned celebration for health reasons. Nor could he foresee a time when he would be well enough for such an event.

Both Bishop Hughes and James McMaster avoided commenting on the presence of the Italian hero in their midst. If the suspicions of the New York papers were right, Hughes was working behind the scenes to discourage any outpouring for Garibaldi. Meanwhile, McMaster continued using his newspaper to assail the Risorgimento, the “resurgence” aimed at unifying Italy politically and recovering its cultural prestige.

In October, Garibaldi moved from Manhattan to Staten Island to live with Meucci in the village of Clifton. Garibaldi wanted to work, and Meucci came up with the idea of opening a sausage factory. When that business failed, Garibaldi worked in a candle factory started by the enterprising Meucci. For recreation, he went fishing with Meucci in a small boat with a sail painted in red, white, and green. He also hunted in the wooded Dongan Hills near Staten Island’s eastern shore, south of what would one day be the Staten Island Expressway. This outing led to his arrest for violating a minor town ordinance—a case the magistrate quickly voided when told who Garibaldi was. Garibaldi took walks on Richmond Terrace on Staten Island’s north shore, went to the market in Stapleton, a village on the island’s northeast corner, across the harbor from lower Manhattan, and played bocce on New York Avenue, near the shore. His neighbors, though aware of his fame, viewed him as a simple workingman. This quiet period helped Garibaldi to recover from his jarring wartime experiences. In any case, it would have done him little good to spend his days rousing New York’s Italians to his cause since their numbers were so small. There were many Irish to oppose him, however, and Garibaldi’s low profile in Staten Island allowed him to avoid a useless conflict with them. Instead, he prepared himself for the revolutionary struggles that were still to come.

Giuseppe Garibaldi ultimately returned to fighting in Italy, conquering Sicily and southern Italy in 1860 in a stunning triumph that delighted most Americans, especially the few Italians among them. But it scandalized Irish Catholics, who could see that the Italian nationalists were advancing again toward the pope in Rome.

***

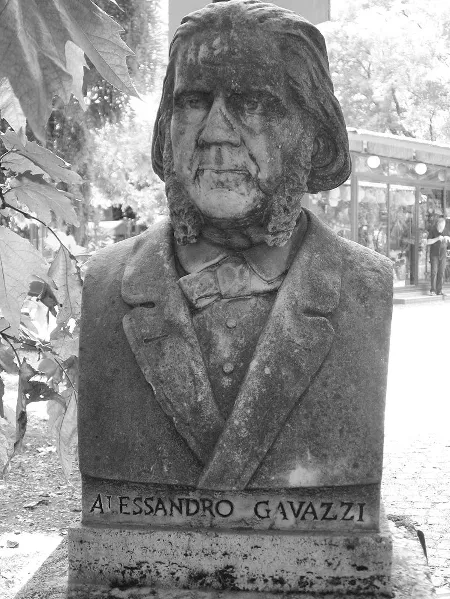

While Garibaldi lived with quiet dignity in New York, that wasn’t the case for another visiting Italian revolutionary. The turncoat priest Alessandro Gavazzi, known for his fiery orations against the Catholic Church, received a hero’s welcome in the New York papers when he arrived on March 20, 1853. He had been invited to America by Protestant organizations campaigning to win over Catholic converts, and his slashing attacks on Pius IX and on core Catholic beliefs contributed to “Know Nothing” sentiment against Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Germany.

Gavazzi was greeted with prolonged applause and a flutter of waving handkerchiefs—“with an enthusiasm we have seldom witnessed,” the Times said—when introduced at the Broadway Tabernacle, several blocks north of City Hall on Broadway near Worth Street, on the evening of March 23, 1853. Six pillars encircled the space around one of America’s most powerful pulpits, and beyond them were 2,400 packed seats. From this, the first of his many lectures, Gavazzi seemed especially interested in provoking the Irish—with the aim, as he put it, of saving them from the pope.

“The Popish religion is the personification of the Monarchical Government,” he charged. “In your country, this large Irish emigration is intended to overthrow your American freedom.” These were obvious fighting words, hurled in the face of now-Archbishop Hughes—who, organizers later discovered, was present in the audience in disguise. Even so, Hughes did not respond directly.

But Patrick Lynch, editor of the Irish American, was disgusted at what he read in the morning papers and sent an earnest letter of protest to the Times. Lynch, who had emigrated from Limerick in 1847, said it was clear that Gavazzi had “aimed at exciting and directing the Protestant animosity of Americans against Irish Roman Catholics.”

After nearly a month of crowded speaking engagements, Gavazzi decided to provoke the Irish to their faces, running a free event so that the impoverished immigrants would attend. A handsome, tall man with long, dark hair, Gavazzi wore black robes with a red cross emblazoned in the center of his chest. He argued for the superiority of Protestant countries over Catholic ones. “Everywhere, my dear brethren, the Papists are poor, miserable, unclean; and the Protestants, rich and prosperous,” he declared, to a storm of hisses from the Irish, many of them Famine survivors.

He recounted his travels in Ireland ten months earlier. In Belfast, he went on, Protestants had established many factories, while the Catholics had little. Wherever he went in Ireland, Gavazzi said, he saw filthy, miserably furnished Catholic cottages side by side with neat, well-furnished Protestant cottages. The Catholics always blamed the English for their poverty, but instead they should “reproach your priests, who oppress and rob you,” Gavazzi urged, insisting that the Irish enjoyed liberty under the British. The priest echoed a common British response to the Famine: the Irish were poor because of their own flaws and would not have been starving if they were more disciplined.