![]()

1

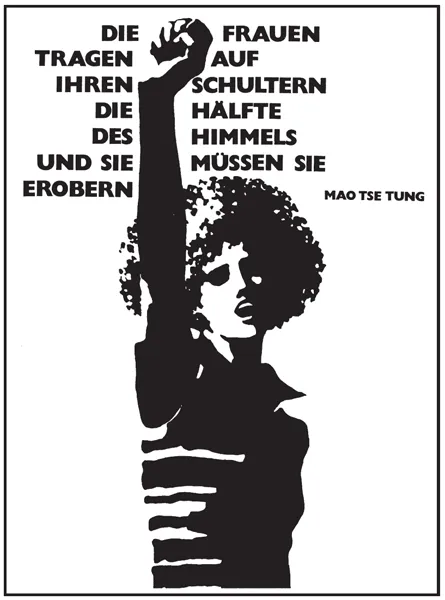

The Other Half of the Sky

Revolutionary Violence, the RAF, and the Autonomous Women’s Movement

Protest is when I say I don’t like this. Resistance is when I put an end to what I don’t like. Protest is when I say I refuse to go along with this anymore. Resistance is when I make sure everybody else stops going along, too.

★ Ulrike Meinhof quoting a Black Panther activist, 1968

Women carry half of the sky on their shoulders and they must conquer it.

★ Mao Zedong

Male violence has settled within my body, has broken my voice, constrained my movements, has blinded my imagination: the female body as microphysics of patriarchal violence, faceless identity, formless history, invisible labor, called love.

★ Anna Dorothea Brockmann, 1981

Introduction

During the early 1970s, a flyer with the image of a woman with her fist raised to the sky was passed around in radical political circles in West Germany. The upper part of the image displays a quotation from Mao Zedong: “Women carry half of the sky on their shoulders and they must conquer it” (see figure 1.1).1 With the woman’s Afro and raised fist, the image connotes anticolonial movements, evoking associations with movement icon Angela Davis of the Black Panthers. This flyer and its distribution in activist circles speaks to one of the central issues of this book: the role of women in revolutionary movements in West Germany (including their employment of political violence) and what that implies for feminist politics. Visually, the image makes two points: first, it offers revolutionary violence (symbolized by the raised fist) as a means to a better world; second, it suggests that women have a central role to play in this process. The actual gender politics of the Left were much less integrated than Mao’s statement suggests; however, the flyer does visualize a convergence of feminist goals and revolutionary violence that is mirrored in the RAF women’s presence in the political scene. This convergence troubles the historical separation of feminist politics and violence and instead demands a realignment of categories of women’s political activism.

Understanding the multidimensional approaches to violence that existed in the West German leftist activist scene is important to theorizing its gendered implications. The following reflections on the political and theoretical contexts that produced the RAF and the women’s movement in West Germany are thus necessarily narratives about violence, focused on the role it (imaginatively and actually) played in various activist settings, the seduction and temptation it posed for some and the horror and repulsion it evoked in others. The seemingly dualistic approach to the complicated matter of movement activists arguing for diverse political positions does not imply that all leftist activists were violent or that all feminists opposed political violence. However, it acknowledges the center stage that the question of violence took in the political organizing of that time.

Before turning to feminist discussions on political violence, it is necessary to establish the context of this particular historical moment in West Germany of the 1960s to the 1980s. This context, in which the use of violence was intensely debated by activists in Western nations, sets the stage for the analyses of gendered terrorism in the rest of the book. During this time, domestic political issues were interpreted in the larger context of the Vietnam War, the Cold War détente, and anticolonial and/or liberationist struggles in Africa and anti-imperialism in South America, which cast U.S. imperialism as the contemporary manifestation of fascism. The context analysis in this chapter does not represent a history of social movements in West Germany, but offers instead a narrative of how the discursive force of violence (conceptually and actually) shaped political formations. This narrative is formulated around two main parts at the center of the debate on political violence in West German activist circles. One frames violence as the oppressive foundation of political resistance, thus creating a need to organize. Leftist activists (and later the RAF) understood this violence to be based in imperialism and its racist wars, fascism and its political workings, as well as capitalism’s global and domestic exploitations. Feminist activists, on the other hand, understood violence to be based in patriarchy (an analysis that initially included what was viewed as patriarchy’s destructive offspring/extensions, imperialism and capitalism) and to manifest in (sexual) violence against women.

Both leftist and feminist political positions harbored a particular suspicion of “democratic” procedures as simply disguising existing power structures (such as the West German parliamentary politics making invisible surviving fascist/authoritarian ideologies, interests, and practitioners, or promoting inherently patriarchal values and barring women from social and political power), and thus both groups took radical, antistate political positions. However, their takes on how to counter violence differed markedly on the basis of their opposing philosophical views. This second part of the debate, which focused on the political means to counter violence, conveys the diverging conceptual emphases around which activists would rally. Radical sections of the Left, and especially armed groups, viewed actual (not symbolic) violence as a necessary and singularly effective way of meeting systemic violence, while many feminists thought violent resistance would simply reproduce existing destructive patterns.

Maybe most importantly, in leftist discourse, power and oppression were externalized forces to be fought against. While a leftist analysis of capitalism and imperialism necessarily seems to include an examination of one’s own class privilege, often a simple rejection of a “bourgeois” lifestyle and declared solidarity with Third World peoples seemed to establish shared grounds with those in need of defending themselves against state violence, and fascism was constructed as the parent generation’s social disease. This is not to claim that all leftist activists were privileged or uncritical of themselves; the social background of many of them included the experience of poverty, an abusive foster care and/or educational system, and social stigmatization. Rather, the point here is that the theoretical reasoning that solidarity can be the grounds for revolution (as it was initially formulated by the SDS and taken to its logical consequence by armed groups like the RAF) does not resonate with a feminist sensibility that locates liberation/revolution in the resistance against personal, everyday sexual oppression. Instead, feminist criticisms of the everyday privileging of men posited every individual man to be a representative of oppressive power relations (this criticism meanwhile problematically released women from accountability for their power, based on factors such as their class, nationality, and/or race). The feminist claim that the “enemy” of patriarchal domination infested even activist circles challenged the construction of West German activist men as having successfully rejected their inheritance of social and political power, a narrative central to the legitimization of armed resistance.

Revolutionary Violence

Placing revolutionary violence and feminist nonviolence into conversation means recognizing their shared historical and political context of the New Left and the new social movements in West Germany. The early 1970s saw both the consolidation of feminist organizing efforts in the emerging autonomous women’s movement and the radicalization of activists resulting in the formation and political actions of the RAF, the Movement 2nd June, and other militant groups who viewed revolutionary armed struggle as the only effective way to achieve social change. For these activists in armed groups, violence signified not only a political strategy but also a philosophy that viewed actual, physical conflict as a necessary prerequisite for change. According to the statement on the formation of the Movement 2nd June in 1972, “The militaristic stance of the Movement 2nd June cannot be separated from its political stance and is not secondary. We view both stances as inseparably connected. They are two sides of the same revolutionary cause.”2 This group side-stepped the ethical dilemma activists of the New Left struggled with: whether violence—against property and/or people—is legitimate. Revolution, they reasoned, cannot be talked into existence. Instead, only actions can facilitate social change—in this case, actions of violent resistance. Instead of writing and talking about revolution, they demanded, people must act as revolutionaries. This call to action is addressed in the RAF position paper “Das Kouzept Stadtguerilla” (“The Concept of the Urban Guerilla”) in 1971: “The Red Army Faction speaks of the primacy of practice. The question, whether it is right to organize armed resistance at the current moment depends on whether it is possible; whether it is possible can only be determined through practice.”3 This credo of the “primacy of practice” that would be the RAF’s main argument against criticisms from within the movement reduced the New Left’s principle that “solidarity [with the armed struggle of peoples in the Third World] must become practical”4 to the one option of going underground and attacking the state.

These activists did not step out of nowhere into the underground: they formed their extremist political positions in the context of West Germany’s leftist subcultural milieu. While some scholars suggest that the student movement propagated the use of violence much more than discourse had previously depicted,5 others have convincingly argued that large numbers (probably the majority) of people organizing around leftist political issues sought alternative strategies from those presented by polarized positions.6 Maybe more importantly, the way violence as a concept circulated in leftist circles was much more complicated than planting bombs and carrying guns. However, within the smaller radicalized circles whose members’ direct-action strategies and street violence with police were already located in the “grey” zone of political activism, violent rhetoric (and action) was part of the political repertoire. So instead of constituting an isolated phenomenon, the prioritizing of violence against the state and its representatives over other forms of political strategies by groups like the RAF and Movement 2nd June can be understood as the development of an extreme section of a much broader discourse on violence that was taking place in the countermovements of the 1960s.7 The terrorism of the RAF and Movement 2nd June thus needs to be contextualized in the wider narrative of revolutionary violence that in the 1960s shaped much of international and domestic organizing throughout the world, including in West Germany. Certain radical approaches to political issues dominated parts of the APO (Außerparlamentarische Opposition, or Extraparliamentary Opposition),8 the New Left’s most concrete formation in the 1960s, and the radical political scene throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s. During the 1960s, many members of the APO conceptualized their radical, countercultural lifestyle and their direct-action approach to politics as counterviolence to a brutal state and corporate system. Actions included the campaigns and protests against the publishing giant Axel Springer and its reactionary tabloid Bild as well as the massive and violent protests against the Iranian shah. During the 1970s, the reframing of medical discourse on mental illness as politically oppressive by groups such as the Socialist Patients’ Collective (SPK),9 militant actions against nuclear facilities (both weapon positioning and waste storage), and the increasing number of squatting projects in the urban centers all involved rhetoric and actions of violence. Finally, during the 1980s, the emergence of the Autonomen10 and their militant street politics as the most visible element of radical leftist organizing form an important historical backdrop for armed groups like the RAF (1970–1998) and the Movement 2nd June (1972–1980). While the aim here is not to paint radical leftist German political activists as generally violent (the majority maintained a consistently ambivalent relationship to political violence), the goal is to avoid a defensive denial of the fact that violence has constituted an important part of leftist politics—in particular as a response to state and other violence.

This being said, it is important to understand the West German debate on political violence to have taken place in conjunction with international radical social movements (including armed revolts) against former colonial regimes, a brutally fought war on the Indochinese Peninsula, and an aggressive nuclear arms race between two superpowers.11 Those in the West German Left who viewed violence as one necessary element of revolutionary change conceptualized their radical politics in close relation to happenings globally and to the theories on revolutionary violence that were circulating internationally.

Snapshots of the 1968 Movement and the APO

If you were a young activist with radical leftist politics in 1968 in Paris, Berlin, Rome, Berkeley, Prague, or Montevideo, revolutionary violence as a means to disrupt the oppressive state was debated rigorously and passionately in your political circles. In West Germany two developments galvanized the protest movements leading up to the year of international revolts in 1968: one involved the impending Emergency Laws that would allow for the curtailing of democratic rights during times of crisis,12 and the second was the formation of the “Great Coalition” in 1966 between the two major political parties—the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the sister parties Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Bavarian Christian Social Union (CSU)13—that effectively eliminated any opposition in Parliament. The “Great Coalition” spurred on the formation of the Extraparliamentary Opposition (APO) that had begun to emerge in the early 1960s. The APO saw itself as the only true oppositional force against the government; it stood separate from party politics and worked outside the electoral process. APO activists organized projects that challenged institutional and cultural authority. While the APO consisted of a variety of political groups, the student movement took a leading role; in particular, its formal body, the SDS,14 and its leaders became the “faces” of the New Left, especially Rudi Dutschke. In their early years, the APO organized against rearmament, the basing of nuclear weapons in West Germany, and the proposed Emergency Laws. Later, their activities included campaigns against the conservative publishing house Axel Springer and its notorious tabloid Bild, the public exposure and confrontation of former Nazi officials and professors, protests against the Vietnam War and the Iranian shah’s regime, and other organizational collaborations with international students and activists.15

The students’ criticism of German politics and what was viewed as a static, conservative society in general was driven by a con...