![]()

1

According to the Customer’s Desire

The First Delicatessens in Eastern Europe and the United States

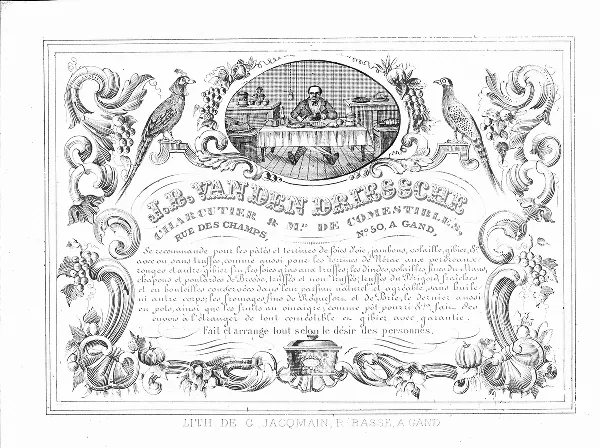

An illustrated advertising postcard from a Belgian butcher and food shop from the mid-nineteenth century is decorated with colorfully plumed birds, clusters of grapes, and an iron cooking pot on the bottom. A petite oval at the top, as if a window into an upper-class home, shows a nattily dressed gentleman sitting at a table with knife and fork in hand, preparing to dig into a feast of fancy foodstuffs. The caption, in French, lists all the meats, cheeses, pâtés, and other items that are available for purchase from the shop, which promises that everything will be prepared “according to the customer’s desire.”1

Perhaps it should not surprise that the pastrami sandwich became an object of such potent and piquant obsession in Jewish culture, given that the very word delicatessen derives originally from the Latin word delicatus, meaning “dainty, tender, charming, enticing, alluring, and voluptuous.” Indeed, the Romans often used the word to refer to sexual attractiveness, as in the expression puer delicatus, the “delicious” boy, who was the recipient of an older man’s erotic attentions. It entered medieval French as delicat, meaning “fine,” and by the Renaissance morphed into delicatesse, signifying a fine food or delicacy. It was picked up as delicatezza in Italian and Delikatesse in German, both also denoting an unusual and highly prized food. It entered English only in the late 1880s, with the influx of Germans into the United States, and then only in the plural form, delicatessen.

The origin of the delicatessen as a food store derives from the democratization of gourmet eating in Europe. This occurred at some times through political upheavals such as the French Revolution, after which many chefs found themselves out of work, and at other times as a result of papal decrees. Pope Gregory XIII, who was invested in 1572, inveighed against the bishops and cardinals of his day for eating sybaritically despite their purported devotion to austerity and self-abnegation, and he mandated that they could employ no more than one chef apiece.2 Unemployed chefs opened Italian specialty food shops called salumerie in which cured and smoked meats were sold to members of the haute bourgeoisie who, unable to afford their own chef, still desired to eat like a king—or a pope. Among the specialties of these stores were cured meats, which were especially popular in Italy. According to the Harleian Miscellany of 1590 (first collated and edited in the mid-eighteenth century by Samuel Johnson), “the first mess [course] or antepast, as they call it, that is brought to the table, is some fine meat to urge them to have an appetite.”3

Delicatessens competed to provide the most unusual foodstuffs from around the globe. Their ostentatious, symmetrical window displays, which typically featured the head of a wild boar (the origin of the name for Boar’s Head, an American company that was founded in 1905) were likened, by the Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg, to a symphony.4 The most opulent German delicatessen of all, Dallmayr, which opened in Munich during the late seventeenth century (and is still in existence), made daily deliveries to Prince Luitpold of Bavaria. By the late nineteenth century, when the newly unified country flexed its imperialist muscles, delicatessens were also known as Colonialwaren, since most of their products were brought back from German colonies abroad. Dallmayr, for example, introduced the German public to bananas, which it imported from the Canary Islands.

France was not far behind in the realm of imported delicacies. After the French Revolution, the Israeli food and wine expert Daniel Rogov estimated, seventy royal chefs were guillotined, eight hundred opened restaurants, and no fewer than sixteen hundred opened gourmet food shops called charcuteries, which specialized in cured and smoked meats.5 In addition, many of the workers in fine luxury goods transformed themselves into purveyors of fine food and drink. According to a French scholar, Charles Germain de Saint Aubin, writing in 1795, most of the haberdashers, embroiderers, jewelers, goldsmiths, and other high-end artisans in Paris opened food stores, bars, and restaurants; he notes that they had “crowded into the center of Paris to such an extent that it [was] not unusual to find a whole street occupied by nothing but their shops.”6

By eating spiced and pickled meats, along with other gourmet foods, the Parisian bourgeoisie were able to show off their rising economic and social status, just as second-generation Jews were to do in New York a century and a half later by patronizing the delicatessens in the theater district, as we will see. Long before the birth of the overstuffed delicatessen sandwich, these meats had begun to symbolize the achievement of economic and social aspirations, of rising to an elevated status in society.

Pickled Meat in the European Jewish Diet

Cured meats and sausages entered the Jewish diet during the tenth and eleventh centuries, when Jews were living in the Alsace-Lorraine region of France. When they moved eastward in large numbers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries at the invitation of the Polish kings, they brought along what the Yiddish writer Abba Kanter called “this-worldly articles such as Dutch herring, smoked and canned fish, . . . and German sausage.”7 Pastrami, as mentioned earlier, was a Romanian specialty; it originated in Turkey and then came to Romania through Turkish conquests of southeastern Europe, in the area of Bessarabia and Moldavia. The name seems to derive from similar words in Romanian, Russian, Turkish, and Armenian—pastram, pastromá, pastirma, and basturma, words that mean “pressed.”8 Indeed, meat was preserved by squeezing out the juices, then air-drying it for up to a month. Turkish horsemen in Central Asia also preserved meat by inserting it in the sides of their saddles, where their legs would press against it as they rode; the meat was tenderized in the animal’s sweat.

The eighteenth-century French gourmet Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin—who famously said, “Tell me what you eat and I will tell you who you are,” frequently paraphrased as “You are what you eat”—quoted a Croat captain to the effect that when his people are “in the field and feel hungry, we shoot down the first animal that comes our way, cut off a good hunk of flesh, salt it a little (for we always carry a supply of salt in our sabretache) and put it under the saddle, next to the horse’s back; then we gallop for a while, after which,” he demonstrated, “moving his jaws like a man tearing meat apart with his teeth, ‘gnian gnian, we feed like princes.’”9 The etymologist David L. Gold discovered a longer form of the word, pastramagiu, in both Turkish and Romanian, that referred to the person who both made and purveyed the salty, smoky, reddish meat. Interestingly, the ethics of the pastramagiu were suspect; it was a term also used to refer metaphorically, according to a Romanian dictionary, to a “bum, loafer, scalliwag, vagabond; rascal, rogue, or scamp.”10

Given widespread and grinding poverty, meat consumption of all kinds among eastern European Jews was extremely low; historians have speculated that the average consumption of meat per household among the Jews of Poland was about a pound a week during most of the nineteenth century, with poor families eating almost none.11 As Hasia Diner (the Hungering for America author) has noted, beef was especially expensive because of a hefty sales tax. This tax had been originally instituted by Jews themselves in order to provide funds for communal life but then taken over in many areas by the government. The despised tax, called the korobka, thrust most meat out of reach of the poor.12

In “Tevye Strikes It Rich,” the Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem describes what happens after Tevye the Dairyman (later the hero of the pathbreaking 1964 Broadway Jewish musical Fiddler on the Roof, by Jerry Bock, Sheldon Harnick, and Joseph Stein) gives two rich Russian Jewish ladies a lift home on his wagon. The family sets out an immense banquet to celebrate their safe return. Tevye is wide-eyed, realizing that he could feed his family for a week with the crumbs that fell off the table. He is finally invited to join the feast, which includes food that he “never dreamed existed,” including “fish, and cold cuts, and roasts, and fowl, and more gizzards and chicken livers than you could count.”13

Smoked and pickled meats remained rare delicacies for most eastern European Jews well into the twentieth century. They were viewed as a special treat, as one notes in the exuberant klezmer tune “Rumenye, Rumenye” (Romania, Romania). Aaron Lebedeff, who wrote and performed the song, was the most celebrated Yiddish vaudeville star in New York in the 1920s. He punctuated his rendition with popping noises to imitate the sound of uncorking bottles for his favorite meal back in the Old Country, which comprised “a mameligele, a pastromele, a karnatsele—un a gleyzele vayn” (a little polenta, a little pastrami, a little sausage—and a small glass of wine). As the sound of the clarinet goes into ecstatic whoops, the singer recalls the pleasure of eating just a tiny bit of each of his favorite foods.14 Similarly, the painter Mayer Kirshenblatt, who grew up in the Polish shtetl of Opatow in the 1920s, noshed on corned beef only when his uncle brought it back to his own shtetl, Drildz, from business trips to a larger town, Radom.15

For wealthier Jews, pickled beef was a part of their regular diet. Hans Ullman, who grew up in northern Germany in the early years of the twentieth century, recalled the double-walled wooden shed that stood on his family’s farm and that was used to cure meats. Sawdust filled the space between the inner and outer walls of the building. In the winter, the shed was filled with ice from the mill pond, and the ice was covered with more sawdust. Beef was placed in earthenware pots, which were filled with brine and then submerged in the sawdust. After the beef was cured, it was immersed in a series of baths of fresh water to remove as much salt as possible. It was then minced by a servant girl who used a hand-cranked machine that turned the beef into meat loaf or patties.16

Geese and poultry were more available than beef, given the relative lack of grazing land in eastern Europe that was available to Jews, who were barred by the czar from owning land. In Yekheskl Kotik’s memoirs of a privileged late nineteenth-century upbringing in the eastern European town of Kamenits, the author recalled his Aunt Yokheved slaughtering up to thirty geese at once. She cured the geese in a barrel for a month and then served pickled goose meat and cracklings to everyone in her extended family.17

In eastern Europe, Jews were much more likely to own drinking places than delicatessens; indeed, according to the historian Glenn Dynner, the vast majority of taverns in Poland were leased by Jews from the nobility.18 As the memoirist Aharon Rosenbaum recalled of his hometown of Rzeszow, Poland, “There were a lot of taverns in Rzeszow. . . . Given the opportunity, men would sit down and discuss politics or municipal affairs. The best known tavern with the best mead belonged to Yekhiel Tenenbaum whose wife Khana would serve her tasty kigels [kugels, in Lithuanian Yiddish] and cholent [a hearty stew usually served on the Sabbath] to the guests.”19

While few in number, delicatessens did exist in eastern Europe. Memorial Books (Yizkor Buchs in Yiddish)—collections of records and memoirs of eastern European Jews compiled by Holocaust survivors in the 1940s after their towns had been destroyed by the Nazis—often mention delicatessens, where prepared or imported (typically canned) foods were sold. But they make little distinction between them and ordinary grocery stores, such as in an 1891 business directory from Nowy Sacz, Poland, that lists no fewer than thirteen grocery/delicatessen dealers.20 Similarly, a description of the shops next to the market square in the Ukrainian town of Gorodenka reads, “Some stores sold leather and boots, and only a few grocery stores like those of Yankel Haber and Shlomo Shtreyt met the ordinary needs of the citizens of the city. They sold a greater and colorful selection of supplies; some even sold delicatessen.”21 But what was meant by “delicatessen” is not clear.

A memoir of Jewish life in Mlawa, Poland, offers a tantalizing clue. It notes that a particular store “also served as a delicatessen. One could eat a piece of herring and polish it off with a slice of sponge cake, drink a glass of tea or a glass of soda with syrup which was measured out in small wine glasses made of white metal. . . . The Gentiles drank beer and brandy there and gorged themselves on derma and cabbage.”22 And in the town of Kelem, Lithuania, the businessman Yerachmiel Imber owned two different stores, a grocery store and a delicatessen, the latter called Vitmin. This was, in the words of the Mlawa memoirist, “a new and different type of shop in such a small town like Kelem. In it one could buy such things as candies in all varieties, tropical fruits, and other imported and fine delicacies.” In neither of these establishments, it seems, was meat on ...