![]()

1

Millponds, Oysters,

and Early Origins

(1636–1774)

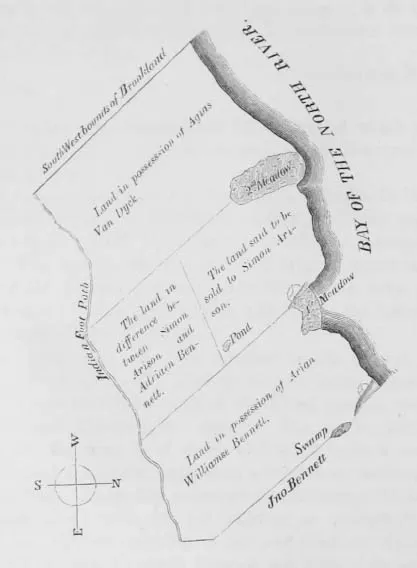

While it’s difficult to determine exactly when the first European settlers arrived on Long Island—sometime in the early 1630s—according to some of the earliest available Dutch colonial documents one of the first official land purchases was made by two Englishmen named William Adrianse Bennet and Jacques Bentin, who bought a large tract of land in “Gowanus” from an Indian chief known as Sachem Ka in 1636.

In the delightful language of early land deeds, the property was demarcated by rural landmarks such as “a certain tree or stump on the Long Hill,” or a “series of white and black oak trees,” one “standing by the Indian foot-path, markt with three notches.” While the exact date of the purchase was lost when the patent document was later destroyed in a fire, it mentions a dwelling house, and thus, according to Henry Reed Stiles—a physician and highly regarded historian most famous for his nineteenth-century, three-volume work History of the City of Brooklyn—suggests that Gowanus was the “first step in the settlement of the City of Brooklyn.”1

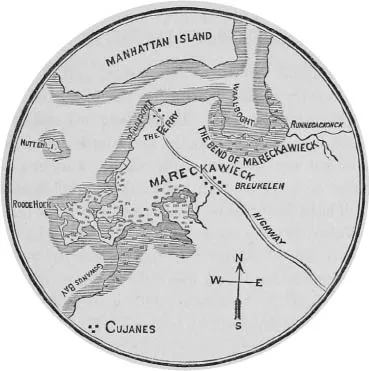

The first European settlers in New Amsterdam arrived from the Netherlands in the early seventeenth century, mostly under the auspices of the Dutch West India Company (hereafter referred to as DWIC). Many of these early settlers were Walloons, or French-speaking Calvinist Protestants, living in the southern part of modern-day Belgium (often referred to as Huguenots). As Russell Shorto established in his incomparable Island at the Center of the World, New Nederland had special appeal due to some outstanding natural features: the massive protected bay and a seemingly limitless supply of fresh water, trees, fauna, and flora that the rumors of the New World had promised. After New Amsterdam was established in 1625, many of new immigrants migrated out in all directions from what is today downtown Manhattan, forded the rivers, and settled around 250 square miles of lush and rugged countryside—in today’s New Jersey and Staten Island to the west, Harlem and Bronx to the north, and Long Island to the east.2

Like the spread of dandelion seeds, small farming communities at the tip of Long Island popped up and bloomed in the lush countryside at the western shores of what the natives called Seawanhacky, or “Island of Shells” after sewant, the shells used as currency for trade—more popularly known as wampum among the New England tribes. Geographically, the modern borough of Brooklyn is a part of Long Island, but in most New York parlance “Long Island” refers to Nassau and Suffolk Counties, the suburban and rural enclaves lying east of the city limits.3

A map of the first land patents of Gowanus, copied from a 1696 survey, printed in the first volume of Henry Stiles’s History of the City of Brooklyn (Brooklyn, 1867).

More or less at the same time as Bennet and Bentin’s Gowanus purchase, records show a grant of several treeless meadows, in the modern-day neighborhoods of Flatbush, Flatlands, and Midwood, purchased from several local natives by DWIC officials on June 16, 1636: “The Director-General and Council of Nieuw Nederland residing at Fort Amsterdam on the Island of Manhattan certify that before them appeared this day, Tenkirauw, Ketaman, Ararykau, Wappettawackensis, owners, who by advice of Penhawis & Cakapeteyno, chiefs in that quarter, have, for certain goods delivered unto them, sold and delivered unto Jacobus Van Curler the middlemost of the three flats to them belonging, called Castateeuw, lying on the island Seawanhacky between the bay of the North River and the East River.”4

A map of the three Dutch settlements of Brooklyn. Henry R. Stiles, History of the City of Brooklyn, vol. 1 (Brooklyn, 1867).

Van Curler, also known as “Van Corlear,” was well known in New Amsterdam as an official under the government of Wouter Van Twiller, the director-general. He owned land in Lower Manhattan (where his name graces an area in southeastern Manhattan once known as Corlear’s Hook), and on the same day, early Manhattan settlers Andries Hudde and Wolfert Gerritsen purchased flats directly west of Van Corlear’s. Director-General Van Twiller himself purchased a massive flat to the east, called Kaskutensuhane, one month later. This massive land grab—the total area of the three plots southeast of the Gowanus amounted to some fifteen thousand acres—was speculative self-interest (an important tradition in New York real estate) since the men neither informed the Amsterdam Council nor asked its permission to buy the property.

On June 16, 1637, exactly one year after the Van Corlear purchase, another settler obtained a patent for a tract of land and freshwater stream called “Rinnegackonck,” from two native chiefs Kakpeyno and Pewichaas, undoubtedly the same individuals from the Flatlands purchase. This buyer was Joris Jansen de Rapalie (also spelled Rapalje), a young textile worker and one of the earliest settlers of New Amsterdam. He and his Walloon wife, Catalina Trico, had arrived in the colonies more than a decade previous and were also some of the first landowners in Manhattan. (They were famous throughout New Amsterdam, and their modern-day American descendants number in the millions.) Trico and Rapalie claimed to have produced “the first Christian daughter in New Netherlands,” on June 9, 1625, though this distinction has long been in dispute. In any event, Sarah Rapalie married Hans Hansen Bergen—one of the few Norwegian settlers in the colony—who became the patriarch of a prolific Brooklyn family whose scions held land in Gowanus for generations. Many early Walloon settlers (most of whom were political asylum seekers who had been camping out in the Dutch university town of Leiden) had made their homes on the much larger island just east of Manhattan.5

Rapalie’s settlement, near the modern Brooklyn Navy Yard, was known as ‘T Waale Boght (also spelled Wahle-Bocht, Waal-Bogt, and later Wallabout) and was about one mile north of the Gowanus Creek. Stiles dubbed this area, known for its majority Walloon population, to which the word Waale Boght is often attributed, as the second milestone in the establishment of Brooklyn.6

(Most of our knowledge of native place-names, such as the Indian settlement known as Werpoes, just west of the head of the Gowanus Creek, or Marechkawieck, the native name of the lands between Werpoes and the Wallabout Bay, derives from such land patents.)7

By 1639, Jacques Bentin, who was once New Amsterdam’s schout fiscal—a Dutch civic position that combined sheriff and attorney general—had sold his Gowanus interest to Bennet for the sum of 360 Dutch guilders.8 That same year, another of the earliest official Gowanus settlers, Thomas Bescher, obtained a land patent on May 17 for “a plot of 300 paces in breadth,” for a certain tobacco plantation “before occupied by John Van Rotterdam, and after wards by him, Thomas Bescher, situate on Long Island, by Gouwanes, in a course towards the south by a certain creek or underwood on which borders the plantation of Willem Adriaensen (Bennet) Cooper; and to the north, Claes Cornelise Smit’s; reaching the woods in longitude: for all which Cornelis Lambertsen (Cool) shall pay to said Thomas Bescher 300 Carolus guilders, at 20 stuyvers the guilder.”9

This patent officially gave Bescher the legal right to own the land as well as sell it, in this case to another settler named Cornelis Lambertsen. The relatively short document reveals several historical gems: Bescher’s sale of Gowanus land was the first recorded transfer of property from one colonist to another in early Brooklyn, and he had purchased an already established and previously occupied tobacco plantation. This indicates that by 1639 the land in Gowanus already held significant agricultural value to these earliest settlers and to the DWIC—especially since the latter finally began to regulate the land after a decade of ignoring it. Colonists would not have lived in any of these settlements before the mid-1630s—an unfortified settlement outside of New Amsterdam would be too dangerous in the beginning, with unknown numbers of wild animals and natives controlling the land. The farmers most likely returned home to the safety of Manhattan after a long day’s work—New York’s first reverse commuters.10

Unlike his predecessor, William Kieft, the director-general who replaced Van Twiller in 1638, did not consider Long Island a cheap source of unauthorized patroonships. On August 1 of that year Kieft organized the purchase of a large tract called “Keskaechquerein,” which extended from Rapalie’s plantation at the ‘T Waale Boght up through current-day Greenpoint, and from the East River to the swamps abutting Newtown Creek. It was the first officially recognized purchase of Brooklyn land by the DWIC. For these roughly four thousand acres, Kieft paid the chiefs eight fathoms of duffel cloth, eight fathoms of wampum, twelve kettles, eight adzes, eight axes, several knives and awls, and a few pieces of coral. One month after this purchase, Kieft changed the colony’s settlement policy: all of New Netherland was awarded free trade by all its inhabitants and friendly nations, and every immigrant was to be granted “as much land as he and his family can properly cultivate.”

Along with this very modern (and very Dutch) policy, Kieft also awarded free passage to the New World to any “respectable” farmers looking to emigrate. This call resonated across Europe and even the English settlements at Virginia and New England. Many farmers, some with considerable means, left to claim their stake to the ample lands in New Amsterdam.11 Thus, the first settlements in modern-day Brooklyn were established at Gowanus, the ‘T Waale Boght, and finally the Ferry, at the foot of present-day Fulton Street in Brooklyn. This last site would prove to be vital to the creation of Brooklyn and to the inhabitants of Gowanus in particular.12

Origins and Taxonomy

What is today the teeming borough of Brooklyn once boasted a lush coastline and dramatic topography. During the earth’s most recent ice age, nearly twenty thousand years ago, massive glaciers carved these beaches and hills, before slowly melting into the ground. But it was only around fifteen hundred years ago that, as the waters receded into New York Bay, Gowanus Creek emerged. Later, practical nineteenth-century Brooklynites dubbed this meandering “tidal estuary”—a partially enclosed body of saltwater with no current other than the movement of the tides—quite accurately “an arm of the sea.” Extending from the watery limb were many streams and offshoots and some freshwater springs, surrounded for nearly a square mile by a lush salt marsh. For good reason and with the same practicality the Gowanus area has often been called a swamp. But modern ecologists would disagree with this nomenclature, since true swamps have trees, while the extensive flooded meadows of Gowanus supported only salt hay and shrubs. These tough grasses are good only for grazing animals or weaving, and grow liberally in the remaining marshes of New York today.13

The earliest occupants of the land around Gowanus Creek were Native Americans, particularly the Lenni-Lenape group of Algonquin Indians. Also known as the Delaware, the members of this once-widespread culture spoke a dialect known as Munsee. Different bands used the surrounding area for seasonal fishing and gathering of shellfish, while the outlying lands were sometimes planted with corn. They lived well off of the ample natural resources, as did the European settlers who came along to claim the land and change the course of its destiny. What we know of Indian day-to-day life comes from the earliest accounts of life in New York, when it was a Dutch settlement known as New Amsterdam, part of the colony of New Nederland.14

“No Long Island name,” wrote the nineteenth-century historian Martha Bockée Flint, “is more puzzling and elusive than Gowanus.” The most popular origin story, repeated by historians of the last century to present-day pedestrians, is that the name refers to a Lenape sachem, or chief, named Gouwane. According to legend, Sachem Gouwane owned a maize plantation south of the Dutch settlement of Breuckelen, giving a name to the creek, bay, and region.15 But while the earliest colonial records of that period, mainly deeds and patents for land sales, reveal the names of several prominent natives conveying land to settlers or the newly established government, none of the documents mention a “Gouwane,” though Gowanus was already an established area. Nonetheless, this interpretation was canonized in the 1901 reference book Indian Names of Places in the Borough of Brooklyn, by William Wallace Tooker, who writes, “The only signification found suggested for [Gowanus] appears in Jones’ Indian Bulletin for 1867 as: ‘the shallows,’ ‘flopping down.’ . . . From the mark of the possessive case the land probably takes its name from an Indian who lived and planted there, Gouwane’s plantation. His name may be translated as ‘the sleeper,’ or ‘he rests,’ related to the Delaware gauwihan ‘sleep,’ gauwin ‘to sleep.’”16

William M. Beauchamp, an ethnologist who wrote Aboriginal Place Names of New York in 1907, praised Tooker’s linguistic expertise and the interpretation of the Gowanus’s origins, and also provided translations such as from gawunsch, “briery or thorn bush,” or gauwin, “to sleep,” as in Tooker’s interpretation. But Beauchamp failed to notice some other names published in his colleague’s work that seem rather coincidental: Not far from Lake Erie in Upstate New York lies a village named Gowanda, to which Beauchamp offers the translation of a “contraction of Dyo-go-wand-deh or O-go-wand-da, meaning almost surrounded by hills or cliffs . . . [a term] still used by the Senecas to describe a place below high cliffs or steep hills, especially if the hills form a bend.” This accurately describes a preindustrial Gowanus, since the environs were a low-lying, bending creek and marsh surrounded by rolling hills. Even more promising is the name Gowanisque (also spelled Cowanesque), a creek in Painted Post, New York. In his work Beauchamp quoted Major J. W. Powell, an adventurous former director of the Bureau of Ethnology at the Smithsonian Institution, who had stated, “The word Cowanesque seems to be no other than Ka-hwe-nes-ka, the etymology and signification of which is as follows: Co, for Ka, marking grammatical gender and meaning it; wan for hwe-n, the stem of the word o-whe-na, an island; es, an adjective meaning long; que for ke, the locative preposition, meaning at or on; the whole signifying at or on the long island. If this is correct the island has now disappeared by changes or drainage.”17 Adding to the intrigue is Lewis H. Morgan, yet another ethnographer and anthropologist, who cited “Gä-wa-nase-geh” as an Oneida word for “a long island” in his League of the Ho-dé-no-sau-nee, or Iroquois, first published in 1901.18

Although Gowanus is indeed at the western edge of today’s aptly named Long Island, scholars are reluctant to draw a connection between the Gowanus and these Iroquois words. Dr. Ives Goddard, senior linguist and Algonquian specialist in the Smithsonian’s anthrop...