![]()

1

The Dark Side of Desire

Racial-Sexual Alterity and the Play of Race

I have been the meaning of rape

I have been the problem everyone seeks to

eliminate by forced

penetrations with or without the evidence of slime and/

but let this be unmistakable in this poem

is not consent I do not consent

—June Jordan1

Sketching the Negress

While June Jordan speaks the unspeakable, black female visual artist Kara Walker helps us both see the unspeakable and consider how this ineffability becomes strategically evoked and used by those we might not expect to articulate such utterances. In her art Walker actively engages the subject of sexual violence and the black female body.2 Her signature black cutout silhouettes, at once mythical, grotesque, erotic, and alarming, function as shadows of the past that evoke the history of sexual violence against black women. Walker’s subject matter, style, media, and even reception have generated much controversy and critique from the art world and beyond. Fellow African American female artist Betye Saar’s epistolary censure of Walker’s work is one of many critiques black artists have made of Walker’s provocative art, largely on the grounds that it replicates “derogatory” stereotypical images of black people, uses racial caricatures, and depicts black abjection.3 Beyond the images themselves, Saar and others objected to the eager reception, indeed “raves,” such imagery generated within majority-white systems of patronage, such as galleries, museums, curators, collectors, and critics.4 Prominent black cultural figures such as Henry Louis Gates Jr. expressed support for Walker’s work. Viewing her art as a critique rather than a rehabilitation of stereotypes, Gates, (re)citing his own theory of signifying, slammed Walker’s detractors for their failure to recognize a pomo parody when they see it.5 Similarly, in her recent incisive analysis of Walker’s schismatic trading in “monstrous intimacies,” the racialized, sexualized violence of slavery, Christina Sharpe contends that Walker’s “work is not simply the recycling of stereotypes.”6 Rather, it emblematizes the constitutivity of this repetition for black female sexuality and subjectivity—the “signifying power of slavery” in the present, “a violent past that it not yet past.”7

If the questions of the stereotype, racist imagery, and its critical reception in black art were compelling, it was because the stereotype is a preferred medium for many black artists—Ellen Gallagher, Gary Simmons, Fred Wilson, Carrie Mae Weems, Betye Saar, and Robert Colescott. The seeming deadlock among those who critique Walker’s art about whether it reproduces or subverts stereotypes resembles the conversation surrounding black women’s current practice of race play—“the peculiar deed” this chapter explores.8 Beyond her use of the racial stereotype, Walker’s work centers on an entanglement of race, sex, violence, and desire convened in, around, and on the black female body. Like black women BDSM practitioners who perform race play, Walker forces us to reckon with what happens when such stereotypes are the stimulus of sexual fantasy and the conduits of sexual desire and with black women’s complicity in this unspeakable pleasure. Walker’s work, an aesthetic articulation of abjection, and the critical discourse in response to it produce a tension similar to that surrounding black women’s participation in BDSM: not merely arousal from violent images or enacting scenes of racial-sexual aggression, but pleasure from a type of violence, steeped in a historical tradition of trauma that forms and informs modern black female consciousness, representation, sexuality, and subjectivity.

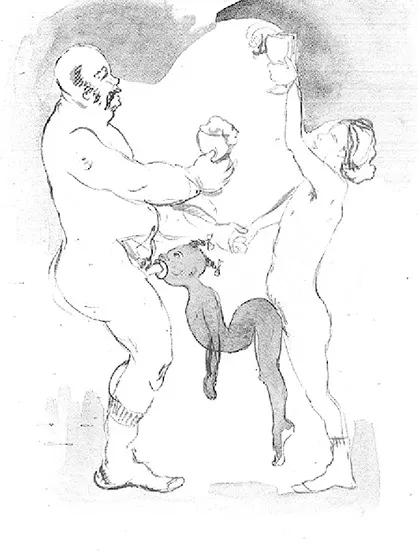

Like black women BDSMers, in particular those who engage in race play, Kara Walker navigates an if not forbidden then certainly conflicted violent topography of gender, race, and sexuality. Walker’s watercolor sketch of a young black female slave being doubly penetrated serves as a clear example.9 The striking image is part of a series titled Negress Notes (Brown Follies) (1996–97). These small paintings—awash with sepia, blue, yellow, and sometimes black—are softer in color, line, and aura than her hallmark bold black-white silhouettes yet are nonetheless searing in subject matter. Similar imagery abounds in her work across media and decades. These loaded images do more than “engage our pleasure centers,” jog our historical memories, and stimulate a collective unconscious.10 They trip the live wires of memory carried in the mind and etched in the flesh. Black women writers such as Hortense Spillers and Elizabeth Alexander speak of this idea of corporeal traumatic memory, of trauma that comes to reside in the flesh as forms of memory that are reactivated and articulated at moments of collective spectatorship.”11 Kara Walker actively withdraws from this epidermal bank. Simultaneously a scathing historical critique of our nation’s public consumption of the black female body in pain and a spectacle of this same pain for public consumption, Walker’s work offers an optimum entrance point for this chapter.

The Evidence of Slime Not Seen

A form of slime itself, slavery remains an active stage for the production of black female sexuality and its representations.12 The impact of chattel slavery and the pervasive rape of black female slaves on modern constructions and representations of black women has been well theorized, in particular by a number of black feminist scholars and historians who have ruptured what Darlene Clark Hine terms “the culture of dissemblance,” the politics of silence shrouding expressions of black female sexuality.13 While the antebellum legacy of sexual violence on black female subjectivity and on representations of the black female body is substantive, how black women deliberately use the shadows of slavery and engage antebellum sexual politics—aesthetically, rhetorically, and symbolically—in the delivery and/or receiving of sexual pleasure has not been adequately considered.14 I am interested in how the evidence of slime—a staining sludge of pain and violence—becomes a lubricant to stimulate sexual fantasies, heighten sexual desire, and provide access to sexual rapture.

In this chapter I explore how black women negotiate a complex and contradictory world of pain, pleasure, and power in their performances in the fetish realm of BDSM. Situating my analysis in the context of the controversial praxis of race play, I argue that BDSM is a critical site from which to reimagine the formative links between black female sexuality and violence. Race play is a BDSM practice that explicitly uses race to script power exchange and the dynamics of domination and submission. Most commonly an interracial erotic play, race play uses racism as a tool of practice, often involving the exchange of racist language, role play, and the construction of scenes of racial degradation. As I reveal here, race play is deeply controversial and contradictory within BDSM communities and beyond. Informed by statements of black women BDSMers about their varied lived experiences with race play, I explore the myriad tensions that animate the practice and its discourse.

I begin with a brief section that frames black women practitioners of BDSM as in conversation with the still-vigorous feminist dialogues surrounding sexuality, violence, and BDSM. Here I am interested in sketching the unique theoretical and practical challenges of the unspeakable pleasures of racial subordination and domination that BDSM presents to black women. I contextualize important debates regarding BDSM’s eroticization of race against those of its equally contentious eroticization of Nazism and fascism. Finally, I examine race play as a particularly problematic yet powerful BDSM practice for black women that highlights the contradictory dynamics of racialized pleasure and power through eroticizing racism and racial-sexual alterity. Women experience the practice in a variety of ways. Assembling these heterogeneous voices, I aim to destigmatize black women’s non-“normative” sexual practices.

I use the term “racial-sexual alterity” to describe the perceived entangled racial and sexual otherness that characterizes the lived experience of black womanhood. Historically, this alterity has been produced (pseudo) scientifically, theoretically, and aesthetically, and it has been inscribed corporeally as well as psychically. The term speaks to the imbrication—the mutually constitutive nature—of racialization and sexualization in the construction of black femininity. Racial-sexual alterity signifies the ways black womanhood is constituted, but not produced solely, through a dynamic invention of racial and sexual otherness. It does not signify a fixed core. Rather, it expresses the importance of both race and sexuality as complex social constructions that are imposed on and enacted by the black female body. It designates a particular, though neither static nor essential, sociocultural experience of subjectivity—one in which sexual categories of difference are always linked to systems of power and social hierarchies. As I argue throughout this book and as pornography makes clear, such otherness is highly ambivalent, oscillating between threat and necessity, desire and derision, sameness and otherness.

Performances of black female sexual aggression, domination, humiliation, and submission in BDSM are critical modes for and of black women’s pleasure, power, and agency. Drawing from textual analysis, archival research, and interviews, I reveal how violence for black female performers in BDSM becomes not just a vehicle of intense pleasure but also a mode of accessing and critiquing power. This work is engaged in deconstructing the “culture of dissemblance” and opening up the dialogue surrounding black women’s diverse sexuality.15 The voices showcased here do more than merely de-silence those of marginalized sexualities or instantiate the discursive production of sexuality, they also constitute the foundation of my claim that race is central to an understanding of BDSM and that BDSM serves as a critical paradigm for racialized sexuality. I use these voices to articulate BDSM as a mode of speaking the unspeakable in black female sexuality. Not heeding the “don’t go there” attitude that often quashes discussions of black women, sexual violence, and sexual pleasure, this chapter follows the unorthodox lead of its subjects and is invested in a type of work that is aligned with what Hortense Spillers might call “the retrieval of mutilated bodies.”16

Negresses Divided: Introducing the BDSM Debate

A consideration of black women’s performances in BDSM necessitates an inquiry into the important feminist debates that such research revisits and reignites. The perspectives of two queer black women writers on BDSM set up the debate about specifically what is at stake for black women. Audre Lorde and Tina Portillo, critical and pioneering voices in black feminist sexual politics, present polarized views on the issue of BDSM, reflecting the enduring binaries that frame the practice. Their voices contest the notion that black queer womanhood was peripheral in the early feminist debates about BDSM, signaling the racialized stakes that continue to frame the practice and how the legacies of black female sexual violence pervade black women’s negotiation of BDSM. For Lorde BDSM is not divorced from but rather operates in tandem with social, cultural, economic, and political patterns of domination and submission. She argues that BDSM perpetuates the inevitability of social domination and subordination,

Sadomasochism is an institutionalized celebration of dominant/subordinate relationships. And, it prepares us to either accept subordination or dominance. Even in play, to affirm that the exertion of power over powerlessness is erotic, is empowering, is to set the emotional and social stage for the continuation of that relationship, politically, socially and economically.17

Lorde’s conceptualization of BDSM echoes that of American sexologist Paul H. Gebhard, who posits that “sadomasochism is embedded in our culture since our culture operates on the basis of dominance-submission relationships and aggression is socially valued.”18 Lorde contends that the same problematic “linkage of passion to dominance/subordination” undergirds both BDSM and pornography.19

In her radical black feminist conceptualization of the erotic as a “life force of women,” Lorde imagines the erotic as not necessarily sexual, but “a considered source of power and information,” “a resource” of “nonrational knowledge” located within a “deeply female and spiritual plane.”20 However, she argues because the erotic has been suppressed by a hetero-patriarchal power, it “has often been misnamed by men and used against women.”21 Her erotic, gendered as woman’s autonomy and power, is antithetical to the pornographic, which she sees as a disavowal of erotic power and a “suppression of true feeling.”22 This view of the erotic further complicates the already conflicted territory between black feminism and pornography. Citing pornography as a “direct denial of the power of the erotic,” Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic” sets the stage for a black feminist critique of pornography, conceptualized as a monolithic cultural entity, that closes off critical consideration of pornography’s erotic potential.23

Though Lorde’s critique of BDSM is not necessarily propelled by black women’s unique location within the practice—for Lorde BDSM is a problem for everyone—her understanding of difference as “the prototypical justification of all relationships of oppression” clearly informs her critique, as it does her later exegesis of the erotic itself.24 Difference, specifically “the learned intolerance of differences,” is a technique of hierarchical power that Lorde argues must be radically envisioned outside a “superior/inferior mold” as a way to bring women together, not keep them apart.25 Still, her identificat...