eBook - ePub

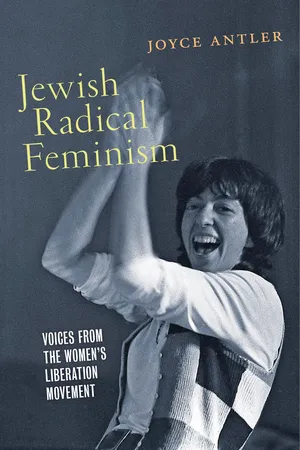

Jewish Radical Feminism

Voices from the Women's Liberation Movement

Joyce Antler

This is a test

Share book

- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Jewish Radical Feminism

Voices from the Women's Liberation Movement

Joyce Antler

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Fifty years after the start of the women’s liberation movement, a book that at last illuminates the profound impact Jewishness and second-wave feminism had on each other

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Jewish Radical Feminism an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Jewish Radical Feminism by Joyce Antler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire du peuple juif. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoireSubtopic

Histoire du peuple juifPart I

“We Never Talked about It”

Jewishness and Women’s Liberation

1

“Ready to Turn the World Upside Down”

The “Gang of Four,” Feminist Pioneers in Chicago

This chapter highlights the story of four young Jewish feminists—Amy Kesselman, Heather Booth, Naomi Weisstein, and Vivian Rothstein—who were in the vanguard of the women’s liberation movement in Chicago as it took shape in the late 1960s. At the time of their involvement with the first glimmerings of women’s liberation, none of these pioneering radical feminists recognized themselves or acted as “Jewish” women seeking a revolution in sex and gender roles. Like the Jewish women who went south to participate in the civil rights struggle a few years earlier, they “just didn’t think of it then.”1 The powerful ideology of the new women’s movement drew them and colleagues of other faiths and backgrounds into a common endeavor that they hoped would radically change society.

The women chronicled their experience as radical feminists and their remarkable friendship in the article “Our Gang of Four: Female Friendship and Women’s Liberation,” published in The Feminist Memoir Project, a 1998 anthology.2 All four were part of the West Side Group, the nation’s first sustained women’s liberation group, which began in Chicago in 1967.3 Friendships such as those that developed among Heather Booth, Amy Kesselman, Vivian Rothstein, and Naomi Weisstein formed a pivotal part of second-wave feminism; they were “central to the energy and insights that emerged among women’s liberation activists in the 1960s,” the Gang of Four wrote.4 Female friendships empowered women and the movement, becoming the matrix for its revolutionary ideas.

“Our Gang of Four” focuses on the women’s family histories and their involvement in the social movements of the 1960s. The one feature that is not mentioned, except in the case of Rothstein, the daughter of Holocaust refugees, is the women’s Jewishness. Until I contacted Amy Kesselman, the four friends had never spoken about their Jewish backgrounds to each other—neither in the article nor in forty years of friendship. Perhaps this was because they perceived little commonality to their Jewish identities or because the issue had never arisen in their feminist work. Or perhaps the women sensed an antagonism between the particularities of ethnicity and religion and the dream of universality that guided the women’s movement. Because they were secular Jews or atheists, the meaning of Jewishness in their lives had been camouflaged by the cultural association of Jewishness with religion and, for some, with middle-class striving and privilege. In the views of some in the group, American Jews had seemed to turn away from a commitment to a social justice agenda. Also problematic was that Judaism did not offer women a central role. Like others in women’s liberation, the four friends focused their attention on class and race as they intersected with the problems of sexism. It was unclear how the constituent elements of American Jewish life fit into this framework.5

As a consequence, the bond of Jewishness among the women remained invisible, though implicit, in their friendship. Only when I came to the four with questions about Jewish identity and its relation to women’s liberation did they begin to explore Jewishness as a personal and political issue. We conducted two long telephone conversations, one about the women’s backgrounds and beliefs as Jews and feminists and the other about the Holocaust, and also shared correspondence on these topics. The stories that emerged point to the significance of Jewishness in these women’s lives, influences that were melded with value systems that developed from the women’s participation in the social networks of their cohort.

Although at the time of the women’s involvement in the movement, they did not acknowledge Jewish influences on their activism, the Gang of Four came from significant but different Jewish backgrounds: secular Yiddish / Communist Party radicalism; Orthodox-Conservative suburban; outsider refugee. Each had some Jewish education, whether formal (Yiddish shul, synagogue, and Hebrew school) or informal (Jewish community centers or Labor Zionist camp). Heather Booth framed it this way: “Many of the elements of Judaism were consciously part of my upbringing.” While several would have specified an antireligious Jewishness rather than Judaism, they might well have shared her appraisal.

For each of the four, ethnic/religious background came together with other elements of personal and collective identity that molded the early women’s liberation movement. “I couldn’t say where one [part of my identity began and one] ended,” Booth said. “Was I who I was because I was in a loving family, because we shared common values, because I was a woman, because I was white, because I was in Brooklyn? They were all part of a common definition.” Fluid and multiple, the varied aspects of identity intermingled, becoming more or less salient over time, depending on social context and the life course. For these women’s liberationists, Jewishness was one of the primary constituents of this mix.

The story of Marilyn Webb forms a coda to this chapter. In graduate school at the University of Chicago, Webb met the Gang of Four and other Chicago feminists and joined the movement to liberate women from the oppressive beliefs and structures of their lives. Moving to Washington, D.C., she was instrumental in starting D.C. Women’s Liberation, one of the most vital of early movement groups. With Shulamith Firestone, Webb participated in a foundational moment of radical feminism at the Nixon counter-inaugural rally in Washington in 1969. Like other Jewish women’s liberationists, she disregarded her Jewish identity during her movement years, only connecting to her roots decades later.

Amy Kesselman, Heather Booth, Vivian Rothstein, Naomi Weisstein: “Our Vision of Beloved Community”

In 1966, fifty women, including Heather Booth and Marilyn Webb of Chicago, attended a national conference of the radical organization Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), at the University of Chicago.6 For three days, the women discussed a memo written the previous year by Mary King and Casey Hayden about sexism in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The first to publicly air grievances against male superiority in the civil rights movement, the memo encouraged the women to think about their own experiences with SDS’s sexual politics, but they were not yet ready to break with the male-dominated New Left.7

The following year and through 1968, groups of young women’s liberationists spontaneously formed throughout the country, organizing to protest the sexism they confronted in everyday life, including on the New Left. Shulamith Firestone, a twenty-two-year-old former Orthodox Jew from St. Louis, was one of the Jewish women whose actions helped to stimulate the rise of women’s liberation in Chicago; other early centers of women’s liberation activism included Seattle, Detroit, Toronto, and Gainesville, Florida.8 Memos and workshops that grew out of SDS and the civil rights movement had been precursors to the formation of these groups.9

Firestone, a young artist studying at the Chicago Art Institute who was unknown to other Chicago activists, came into the spotlight during a weekend convention of the National Conference for New Politics (NCNP) held in Chicago on Labor Day 1967. About two thousand activists had gathered at the conference to debate the Vietnam War, black nationalism, and whether to run a third-party ticket headed by Martin Luther King, Jr., the convention’s keynote speaker, and one of the radical youths’ most admired figures, Dr. Benjamin Spock.10

Backroom conniving mixed with pandemonium on the ballroom floor at Palmer House, where the convention was held. A women’s caucus met for days, framing a minority report that called for free abortion and birth control; an overhaul of marriage, divorce, and property laws; and an end to sexual stereotyping in the media. But conference chairman William Pepper refused to accept the women’s report, calling it insignificant. He told them that in any event, he already had one from a women’s group, Women’s Strike for Peace, even though theirs addressed peace issues, not gender. Allowing a young man to address the NCNP about a Native American resolution, Pepper refused to permit women’s caucus representatives to speak. “Infuriated, we rushed the podium,” activist Jo Freeman recalled, “where the men only laughed at our outrage. When Shulie reached Pepper, he literally patted her on the head. ‘Cool down, little girl,’ he said. ‘We have more important things to do here than talk about women’s problems.’ Shulie didn’t cool down and neither did I. . . . The other women responded to our rage. We continued to meet almost weekly, for seven months. . . . We talked. And we wrote.”11

Following the incident, Firestone and Freeman organized the Chicago West Side Group, so named because it met at Freeman’s house on the west side of the city. In addition to Freeman and Firestone, members included Amy Kesselman, Fran Romanski, Laya Firestone (Shulamith’s sister), and Heather Booth and Naomi Weisstein, whose course on women at the Free University at the University of Chicago, first taught in 1966, served as a catalyst for Freeman.12 Vivian Rothstein, Sue Munaker, and Evelyn (Evi) Goldfield came six months later, with Linda Freeman and Sara Evans Boyte joining within the year. These dozen women were the regulars, although another dozen or so variously attended meetings.13 The West Side Group used the phrase “women’s liberation” in an early article and in its newsletter, the Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement, published from 1968 through 1969, helping to spread the goals of the movement around the country.14

“Ready to turn the world upside down,” in Naomi Weisstein’s words, the West Side women “talked incessantly”: “We talked about the contempt and hostility that we felt from the males on the New Left, and we talked about our inability to speak in public. Why had this happened? All of us had once been such feisty little suckers. But mostly we were exhilarated. We were ecstatic.”15 It was as if the NCNP “had broken a dam,” Sara Evans wrote in Personal Politics, one of the first histories of the movement. When the Chicago women heard the message—“sometimes in the form of the words ‘women’s liberation’—their first response, over and over again, was exhilaration and relief.”16

Jo Freeman gave Heather Booth credit for spinning off new women’s liberation groups in Chicago, where several new groups formed. Through the New Left, “she had the connections,” Freeman recalled, “and she had the commitment.”17 Shulamith Firestone, who left Chicago for New York a month after the founding of West Side, helped organize the first women’s liberation meeting in New York two months after the Labor Day conference in Chicago. By the next spring, Firestone had prodded the New York group, which took the name New York Radical Women, into producing its first collection of writings, Notes from the First Year. When Kathie Amatniek (later Sarachild), another New York feminist activist, visited Boston, she persuaded her childhood friend Nancy Hawley to join the growing women’s liberation movement. The following year, Hawley was part of an informal women’s group that would write the revolutionary women’s health book Our Bodies, Ourselves.

The Jeannette Rankin Brigade Protest, a January 1968 peace action in Washington, D.C., organized by the West Side Group and New York Radical Women, helped to promote the movement and, in a flier created by Kathie Sarachild, introduced what was to become its trademark slogan, “Sisterhood Is Powerful.”18 The movement was spreading like “wildfire,” commented Ann Snitow, a member of New York Radical Women. “We called ourselves brigades and we founded a whole bunch of other brigades; we cloned ourselves.”19

By April 1968, approximately thirty-five small radical women’s groups concentrated in big cities were on the map; by the end of the first year, there was “hardly a major city” without one or more.20 The groups formed spontaneously, as women sought each other out for support and to discuss specific abuses.21 While focused on general women’s liberation issues, each group reflected the overall emphases of the area in which it formed.22 “New York City is the culture capital. Chicago, heavy industry. We were the edge, you the heartland,” Rosalyn Baxandall of New York City wrote to Naomi Weisstein, pointing to one of the regional differences that shaped early radical feminist groups.23

To create a wider coalition, Marilyn Webb and several colleagues organized the first nationwide gathering of women’s liberationists at Sandy Springs, Maryland, in August 1968. There, twenty participants spent a tense fall weekend arguing about whether men or capitalism was the greater enemy and castigating themselves for the failure to involve black women in the incipient movement. As an outcome of the meeting, Webb, with Laya Firestone of Chicago and Helen Kritzler of New York, organized a conference to commemorate the 120th anniversary of the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls. Due to their efforts, two hundred women came together at a YWCA retreat in Lake Villa, outside Chicago, during Thanksgiving week, but this larger meeting was also wracked by controversies between “politicos” (arguing from the New Left position that women’s oppression derived from capitalism) and pro-woman “radical feminists” (urging an autonomous women’s movement since men were the ultimate oppressors).24

In Chicago, the West Side women wrestled with their allegiance to the male-dominated Left but believed that their group marked an important step away from the masculinist emphases of SDS. After years of being “judged and humiliated” by New Left men, Amy Kesselman exulted in the fact that she had comrades with whom she could openly develop her ideas. But separating from the New Left was extremely difficult—like “divorcing your husband,” she said. Several members of West Side were in fact married to SDS “heavies”: Heather to Paul Booth, a former SDS vice president; Naomi to historian Jesse Lemisch, a member of the original SDS at the University of Chicago and then Northwestern University; Vivian to activist Richie Rothstein.25

Nonetheless, the Chicago women felt that their position inside SDS was “no less foul, no less repressive, no less unliberated” than outside: “We were still the movement secretaries and the shit-workers.”26 They tried to find a balance between the socialist perspectives they shared with male leftists and their conviction that it was essential to challenge male supremacy. The attempt to find a middle ground is reflected in an April 1968 paper, “Toward a Radical Movement,” by Heather Booth, Evi Goldfield, and Sue Munaker, which argued that “there is no contradiction between women’s issues and political issues, for t...