![]()

1

The Post-Soviet Diaspora on Transnational Reality TV

While they have largely been neglected in academic scholarship, residents of the former Soviet Union are often represented in US popular culture. Throughout the 1990s, they continued to be portrayed in Cold War terms as US enemies and mail-order brides or fetishized as political refugees from socialism (Katchanovski 2007; Carruthers 2009). In the late 1990s and early 2000s many Hollywood movies featured criminal characters with Russian and Ukrainian names, referenced the existence of a “Russian mafia,” and depicted “Russians” as terrorists and arms dealers (Katchanovski 2007). Popular serial dramas from the turn of the twenty-first century like NYPD Blue (1993–2005), The Sopranos (1999–2007), and 24 (2001–2010), similarly represented former USSR residents as terrorists or villains.1 A newer series like House of Cards (2013–present) has portrayed Russia and its president as one of the main US adversaries in the contemporary era. At the time of this writing, Special counsel Robert Mueller is investigating Russia’s involvement in the 2016 US presidential elections.

Even after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, highly stereotypical depictions of residents of the former Soviet Union as evil have tended to outnumber those of Muslim Arabs (Katchanovski 2007).2 Since 24’s first season in 2001, for example, its protagonist Jack Bauer of the fictional Counter Terrorist Unit tirelessly struggled to foil more “Russian” terrorist plots than attacks by Muslim Arabs. The “Russian” protagonists in 24 are always former military or KGB agents, come from some unspecified part of the former USSR, speak something barely resembling Russian, and are played by German, British, Irish, and US actors (Ohanyan-Tri 2015).3 The fact that the USSR’s largest successor nations, Russia and Ukraine, and their citizens are more frequently depicted as terrorists than are the residents of an equally homogeneously constructed ideological US opponent located in the “Middle East” shows that Cold War views of a world divided into two ideological camps remain entrenched. Different US enemies are simply conflated to help justify the US wars on terror in the old binary Cold War terms.

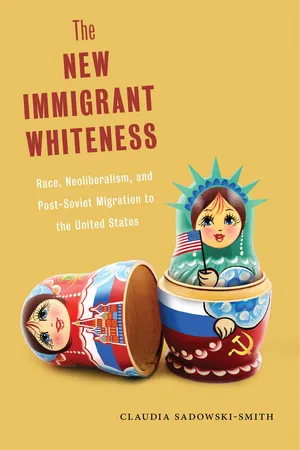

As one of the newest and most widely watched media forms, reality TV shows from the 2000s have lent themselves especially well to portrayals of the post-Soviet diaspora that depart from these established media representations of Russians as major post–Cold War foes. The short-lived 2011 Lifetime show Russian Dolls (2011) and the immensely popular Dancing with the Stars (DWTS), which has been on ABC since 2005, exemplify the emergence of a new narrative that explicitly associates the post-Soviet diaspora with idealized accounts of turn of the twentieth century European immigration. Russian Dolls and DWTS highlight their cast members’ cultural assimilation to a “Russian” ethnicity and their upward mobility into the white middle class as they appear to be following in the footsteps of their supposed European predecessors who assimilated to a pan-European whiteness and whose descendants developed ethnicized identities in the 1960s. Just as turn of the twentieth century European immigrants were often positioned and placed themselves in explicit contrast to African Americans, post-Soviet immigrants are assigned a pan-European whiteness or one of its ethnicized versions through contrast with the largest group of contemporary migrants from Latin America.

The reality TV genre emerged in the late 1990s at a time when the television industry was undergoing drastic transformations. The privatization and deregulation of large sectors of the industry and the subsequent arrival of new cable and satellite channels, created a need for programming that was predominantly driven by economic considerations, such as lower production and airtime cost (Biressi and Nunn 2005, 16). The use of program concepts or so-called formats is a cost-saving staple of reality TV. As they document and systematize the production knowledge gained from the development of a particular show, formats are duplicated or modified for introduction into other national markets in order to save money.4 DWTS is an adaptation of the British Broadcasting Corporation’s most successful reality show format Strictly Come Dancing. While it is not a format adaptation as such, Russian Dolls is modeled after MTV’s notorious docusoap Jersey Shore. As additional cost-saving measures, reality TV shows typically cast nonactors and employ minimal scripting in order to eliminate the need to pay unionized writers and actors. Participants in reality TV shows are placed in highly constructed and often unusual situations that encourage behaviors and interactions designed to produce maximum emotional effect. The live or recorded surveillance footage of these responses is then edited into narrative structures that mimic the storytelling employed in other, more scripted shows and that play to audience expectations by reaffirming familiar views of the social world (Friedman 2002; Biressi and Nunn 2005, 3).

While reality TV thus actively constructs the “reality” it features through production and editing practices, the genre markets itself as providing audiences with unmediated, immediate, and intimate representations of ordinary people in unscripted situations, often by employing the tropes of revelation, truth telling, and exposure through interviews with participants (Biressi and Nunn 2005, 3–4). As it emphasizes drama and conflict to provide maximum entertainment, reality TV also engages with questions that other media forms rarely touch. The genre often addresses issues of individual and collective identity formation, and may even have taken over the task of constructing, not just representing, these identities (Turner 1996, 160).

Dancing with the Stars and Russian Dolls give representational shape to the ongoing construction of a collective “Russian” identity, which the two shows portray as a contemporary version of turn of the century European immigrant adaptation and upward mobility. A game show, DWTS focuses on the relationships between predominantly US-born B-list celebrities and their professional dance partners, many of whom are post-Soviet immigrants who have become stars in their own right through participation in the show. Reality TV promotes the notion that cast members can attain celebrity status through involvement in the genre as a way to gain access to upward mobility. While the two shows depict their post-Soviet participants as updated versions of generic turn of the twentieth century European immigrants, Russian Dolls models its portrayal of post-USSR participants more specifically after Italian Americans. This collective identity consolidated in the 1960s alongside other white ethnicized identities to reference the immigrant roots of European-descended Americans with ancestors from Ireland, Italy, and the Russian empire (M. Jacobson 2006, 5).

The mythologized accounts of turn of the twentieth century European migration that DTWS and Russian Dolls associate with the post-Soviet cast erases differences in the arrival and adaptation of various European immigrant groups. The identities of descendants of turn of the twentieth century Italian migrants thus become interchangeable with those of contemporary post-USSR immigrants. The two shows depict an equally homogeneous ethnic “Russianness” that obscures intradiasporic distinctions, such as cast members’ diverse ethnicities and origins in different Soviet republics and their successor nations. While DTWS and Russian Dolls focus on 1.5-generation immigrant participants who most likely arrived as religious refugees, the two shows consistently downplay the Jewish identities of many of their cast members. Their association with a homogeneous whiteness or with one of its ethnic versions obscures the fact that, unlike other earlier migrants, turn of the twentieth century migration by those of primarily Jewish descent from Russia’s Pale of Settlement did not result in the development of a “Russian” ethnic identity to which contemporary immigrants could assimilate. Turn of the twentieth century arrivals instead largely identified with a Jewish Americanness that had been created by earlier arrivals from Central Europe. To acknowledge that members of the post-Soviet diaspora may be connected to facets of an American Jewish identity, however, would severely complicate the emerging association of the diaspora with a mythologized and monolithic European immigrant whiteness to which Jewishness has a complicated relationship.

Just as the white ethnic identities that DTWS and Russian Dolls attribute to the new immigrants emerged in direct response to and in part as a backlash to the civil rights movements and growing immigration from Latin America and Asia in the 1960s, the two shows’ cast members are ascribed a white racial identity through direct contrast with new arrivals from Latin America. Emerging academic scholarship has similarly associated post-Soviet migrants with processes of racialization that were experienced by earlier European immigrants. As historians of whiteness have established, these migrants first sought entry into and then worked to maintain membership in whiteness by differentiating themselves from nonwhite populations and simultaneously denying their white privilege. The two shows represent members of the post-Soviet diaspora as setting themselves deliberately apart from and often engaging in hostility toward Latina/os. Thus, Russian Dolls devoted an entire episode to addressing prohibitions against interracial dating with Latina/os, while social media and academic discourses surrounding DWTS have focused on how the spray tanning that is used by post-Soviet dancers underscores both their fascination with Latin American dance forms and their efforts to set themselves apart from Latina/os as the main target of anti-immigrant discourses.

Because the two shows’ production of “Russianness” as an updated version of US immigrant whiteness relies on the idea that reality TV grants unmediated access to the “reality” it depicts, it is difficult to determine the degree to which the post-Soviet participants have been complicit in these portrayals. But some of the media commentary surrounding Russian Dolls and DWTS, particularly interviews with the shows’ cast, their use of social media, and their participation in other non-US TV shows where their identity is differently constructed, foreground the neoliberal push factors for post-Soviet emigration, significant intradiasporic differences, and post-Soviet immigrants’ efforts to engage with their homes and counter heightened US xenophobia. An acknowledgment of these factors underscores that post-USSR immigrants experience similar processes of adaptation and transnationalism as other contemporary new arrivals, which creates opportunities for comparative work across various diasporas.

Intergenerational Upward Mobility through Dancesport on DWTS

A BBC franchise, US DWTS is a dance competition and one of the most widely watched reality TV shows in which celebrities are cast. Created in 2005 after an Australian adaptation successfully debuted in the fall of 2004, the US version of DWTS format illustrates how the notion that celebrity status affords access to upward mobility has spread beyond elites and into the larger population (Turner 1996). By casting upcoming, established, or fading B-list celebrities who use the show as a springboard to jump- or restart their entertainment careers, DTWS highlights that reality TV now produces, markets, amplifies, and sells its own stars rather than simply features already established ones (Turner 1996, 156). DWTS follows its celebrities over the span of several months as they are trained by professionals in International ballroom dancing and related styles. Live footage of the couples’ dance performances and of the judging are interspersed with recorded documentary footage of participants’ back stories, rehearsals, behind the scenes moments, and confessional testimonials.

Because it is part of the BBC franchise, the US adaptation needs to reproduce the main generic elements of the original British format, particularly its use of the International style of ballroom, which originated in the United Kingdom in the mid-twentieth century and is considered the most prestigious style of dancing (McMains 2006, 95). This style differs significantly from the type of ballroom dancing that developed in the 1920s in the United States and has been most widely taught here. To be able to showcase International ballroom, the US version of DWTS cast a large number of foreign-born professionals who were trained in this style and participated in its dancesport version in locations outside the United States. Out of the original six professionals cast in the first season of DWTS, four were foreign born, and one, Alec Mazo, had emigrated from the former USSR as a child. When the cast was significantly expanded in 2006, several post-Soviet dancers were added as regulars. They included Maksim Chmerkovskiy, Karina Smirnoff, and Anna Trebunskaya. Maksim’s younger brother, Valentin Chmerkovskiy joined the show as a regular in fall 2011. Inna Brayer, who came to the United States as a young child and several first-generation immigrants, including Elena Grinenko, Dmitry Chaplin, and Anna Demidova, have also appeared in several seasons of the show. Gleb Savchenko and Artem Chigvintsev, who both left Russia as adults, were added in the last few seasons.

In addition to hiring talent from Western Europe and Australia, DWTS was able to recruit from a large domestic pool of post-USSR immigrants whose arrival and settlement in the United States coincided with the adaptation of DWTS. Post-Soviet migrants brought with them a high regard for and training in ballroom. In the former Soviet Union, many parents sent their children—both boys and girls—to ballroom dance classes. Rigorous government-supported dance programs also prepared students for international competitions (Berger 2003). After the demise of the USSR, many highly trained ballroom dancers came to the United States and were able to make a living by teaching dance, opening dance studios, and seeking success as dancesport athletes (McMains 2006, 21; Berger 2003). Just as those fleeing Russia’s 1917 Bolshevik revolution made important contributions to the development of US American theater, the much larger migration from the former USSR has initiated a surge in ballroom dancing and an astounding growth in the number of dance studios in the United States. Ballroom dancing continues to be most popular among immigrants from the former Soviet Union and their children, whose parents see participation in the dancesport as a way to achieve the American Dream (McMains 2006, 24; Solomon 2002; “Why Russian-American Jews” 2015). Participation in ballroom is also viewed as a sign of education and a means of creating community (“Why Russian-American Jews” 2015).

Even though the post-Soviet professionals in DWTS were originally envisioned as mere background to the celebrities whose apprenticeship as dancers was to be the focus of the show, over several seasons many of the dancers have become stars in their own right with a loyal following among the show’s audience (Barnes 2011). While US critics have explored issues of gender, ethnicity, and disability on DWTS with regard to the stars featured on the show, the representation of its professionals has not yet received scholarly attention.5 These cast members are not just hired to train celebrities. As members of a new diaspora, they act as what Anne Cooper-Chen (2005) has called “factors of glocalization” that facilitate the introduction of a global reality TV franchise like DWTS to another national media market like the United States. As regulars who have stayed on the show season after season, the professionals have increasingly been featured talking to the stars, the judges, or the show’s hosts. Many of these interactions highlight the post-Soviet dancers’ status as immigrants through an emphasis on their accents and their frequent lack of knowledge of older forms of US popular culture, with which the new immigrants tend to be unfamiliar.

In season 10 (2010) audiences learned more about the show’s dancers through short videos that featured some of their biographies. These clips placed the post-Soviet cast squarely within established narratives of white immigrant success. The videos singled out these professionals from the show’s other foreign-born dancers of Western European and Australian background to highlight their stories of intergenerational upward mobility through immigration and participation in US dancesport. The clips about Chmerkovskiy and Trebunskaya briefly address the migration experiences of the two dancers who came as young children with their families. Trebunskaya is shown talking about her hard childhood in industrial Chelyabinsk, Russia, without providing specific details about the difficulties she experienced, and declaring that dance functioned as a form of escape. Her mother states that the family emigrated to help alleviate her daughter’s asthma. Chmerkovskiy’s immigration story is told by his father, who recounts that the family left Ukraine to provide a better life for their children and to spare their boys mandatory military service.

The video clips reduce the push factors for the families’ migration, including social upheavals following the introduction of neoliberalism, to a more universal immigrant story, according to which movement is driven by the parents’ desire to provide better lives for their children. The clips also never address the legal circumstances under which the families of the two dancers were able to enter the United States. They make it seem as though any family that wanted a better life for their children, especially those from Europe, could just freely enter the United States. The videos thus reify the mythic notion of turn of the twentieth century European migration, particularly from the Pale of Settlement, in which entire families left behind their difficult lives in the “old” country so that the next generation could have better opportunities in the United States and in which immigration was not as tight...