![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

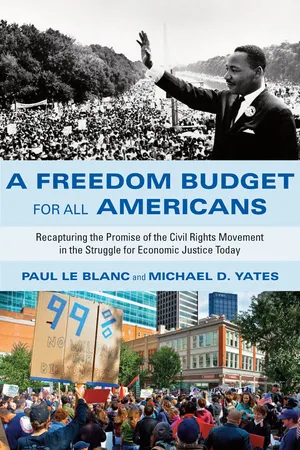

INSEPARABLE FROM THE GOALS projected by the historic 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, A Freedom Budget for All Americans was advanced in 1966 by A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Martin Luther King Jr., central leaders of the activist wing of the civil rights movement in the 1950s and ’60s. It promised the full and final triumph of the civil rights movement. This was to be achieved by going beyond civil rights, linking the goal of racial justice for African Americans with the goal of economic justice for all Americans. If implemented, it would have fundamentally changed the history of the United States. In this introductory chapter, we will first give attention to that larger sweep of U.S. history, and a consideration of the relevance to this of capitalism and socialism, before focusing on the civil rights movement, which—in more than one way—so sharply posed questions of reform and revolution in the American experience.

What Might Have Been and What Was

The Freedom Budget proposal could be seen, and by some was seen, as related to the twentieth-century liberalism that was ascendant in U.S. politics from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal to Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society. But its dimensions and implications were far more radical. It projected the elimination of poverty within a ten-year period, the creation of full employment and decent housing, health care, and education for all people in our society as a matter of right. This was to be brought into being by rallying massive segments of the 99 percent of the American people in a powerfully democratic and moral crusade embracing the civil rights movement, the labor movement, progressive-minded religious communities, students, and youth, as well as their elders.

The defeat of this effort helped set the stage for a historic defeat for all of these constituencies. The crises of the twenty-first century’s first two decades cannot be separated from these defeats—just as keys to the positive resolution of those crises may be found in an exploration of what the Freedom Budget was, where it came from, what it might have done, and why it was defeated.1

This defeat was related, in part, to a well-financed and steady (and soon accelerating) conservative onslaught that culminated in the right-wing triumph of the Reagan-Bush years. If the Freedom Budget had been successful, a majority of the voters would not have responded positively to candidate Ronald Reagan’s challenge to Democratic incumbent Jimmy Carter when the conservative hopeful asked the American people, at the conclusion of a televised 1980 debate: “Are you better off than you were four years ago? Is it easier for you to go buy things in the stores than it was four years ago?”2

The 1980s victory for “free market capitalism,” embraced by most conservative Republicans and by many Democrats in succeeding years, has made things worse for the great majority of the people over the four decades that followed, although certainly not for the wealthiest and most powerful 1 percent. Living standards, health, education, welfare, public transit, urban and natural environments, working conditions, job satisfaction, and more have dramatically declined.3

For many U.S. residents in the 1960s, this future was unimaginable. Since the 1930s, capitalism had yet to face another global downturn, and the common wisdom was that there would not be another. U.S. politics had been more or less dominated by a relatively generous social-liberalism since the coming of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal during the Great Depression, maintained to a significant degree by Republicans as well as Democrats.

In 2008, many hoped the presidency of Barack Obama would bring us back to that better, more hopeful, more generous world (personified in the minds of many by John F. Kennedy), and do it in a way that would be even more inclusive and more than what had been possible in the 1930s and 1940s of FDR’s America. Obama’s enemies cursed this darkly as “socialism”—and for some of his supporters, that s word seemed not so horrible after all. But the realities of the Obama administration never matched his rhetoric, and even his rhetoric fell far short of what Roosevelt eloquently expressed during the Second World War as his vision of the postwar future of the United States.4

Capitalism and Socialism

Roosevelt’s administration had been characterized by aggressive and expansive support for labor rights, encouragement of the formation of powerful industrial unions, generous social programs, and government challenges to conservative business interests. In 1960, Afro-Caribbean cultural critic and revolutionary C. L. R. James commented:

That was the great contribution of Roosevelt to American capitalism, others will say to American democracy. It was a tremendous political feat, and Mr. Roosevelt and his wife [Eleanor Roosevelt] together have a place in American history and the minds of the American people which will never be forgotten. Before Roosevelt and the New Deal, free enterprise and independent action by yourself for everything reigned as the unchallenged ideology of the United States. When Roosevelt was finished, that was finished. The Government was now held responsible for those who were in difficulties owing to the difficulties of capitalist society. In most of the countries of Western Europe, this had been carried out directly or indirectly by proletarian or labor parties of one kind or another. Roosevelt carried it out in the United States through the Democratic Party.5

It should be added that Roosevelt himself was an upper-class reformer who was simply seeking to save U.S. capitalism in the 1930s decade of economic collapse and radical insurgency, but willing to denounce as “economic royalists” those members of his class who attacked him as being “socialistic” because of his sweeping social reforms and support for workers seeking to organize unions. Though he was happy enough to switch from being “Dr. New Deal” to “Dr. Win-the-War” in 1941, his rhetoric veered even further leftward in his efforts to explain and mobilize popular support for the U.S. war effort during the Second World War. In 1941, Roosevelt’s State of the Union address advanced a “four freedoms” orientation designed to rally the American people and U.S. allies in the global struggle against the Axis Powers of Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, and Imperial Japan:

In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms. The first is freedom of speech and expression—everywhere in the world. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way—everywhere in the world. The third is freedom from want—which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants—everywhere in the world. The fourth is freedom from fear—which, translated into world terms, means a worldwide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor—anywhere in the world.6

In his State of the Union address of 1944, Roosevelt expanded on the “freedom from want” theme by outlining what he called a Second Bill of Rights:

It is our duty now to begin to lay the plans and determine the strategy for the winning of a lasting peace and the establishment of an American standard of living higher than ever before known. We cannot be content, no matter how high that general standard of living may be, if some fraction of our people—whether it be one-third or one-fifth or one-tenth—is ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-housed, and insecure.

This Republic had its beginning, and grew to its present strength, under the protection of certain inalienable political rights—among them the right of free speech, free press, free worship, trial by jury, freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures. They were our rights to life and liberty.

As our nation has grown in size and stature, however—as our industrial economy expanded—these political rights proved inadequate to assure us equality in the pursuit of happiness. We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. “Necessitous men are not free men.” People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.

In our day these economic truths have become accepted as self-evident. We have accepted, so to speak, a second Bill of Rights under which a new basis of security and prosperity can be established for all—regardless of station, race, or creed. Among these are:

• The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the nation;

• The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation;

• The right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living;

• The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad;

• The right of every family to a decent home;

• The right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health;

• The right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment;

• The right to a good education.

All of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being. America’s own rightful place in the world depends in large part upon how fully these and similar rights have been carried into practice for all our citizens. For unless there is security here at home there cannot be lasting peace in the world.7

Roosevelt’s expansive rhetoric did not result in the implementation of an “Economic Bill of Rights,” but a number of New Deal social programs were preserved, in some cases expanded, in the years after the defeat of the Axis Powers. His successors, engaged in a new Cold War confrontation with Communism,8 were especially concerned to prove to U.S. workers that the American status quo was pro-labor and capable of providing a decent life for most working people.

The end of the Second World War had opened into a period of prosperity, buttressed by the social safety nets and modest government regulation of the corporate capitalist system, initiated under Roosevelt. As we have noted, this was maintained, more or less, by Democratic and Republican administrations alike from 1945 through 1980. There were frictions and fissures, however, that pushed against this liberal predominance, especially: (1) an anti-union conservatism permeating the South (where the white and segregationist Democrats ruled), and (2) intense conservative dissatisfaction among some Republicans, highlighted by the 1964 Goldwater insurgency and post-1964 ferment.

Many analysts at the time viewed such dissonance as constituting last gasps of the past, not the wave of the future. They were not alert to the migration of the formidable forces that changed the South’s racist Democratic Party into a rightward-moving Republican Party, whose evolving ethos and policies replicated much of what had dominated so much of southern politics of earlier years: low taxes, low wages, a non-union labor force, minimal social services, buttressed by an extreme social and cultural conservatism.

In the face of a decline in U.S. power and profits in the global political and economic arena, the so-called Reagan Revolution was initiated in the 1980s. A succession of presidents—Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Democrat Bill Clinton, and finally George W. Bush—proceeded to cut away more and more of the social safety net, push back and break the power of unions, dismantle government regulations, and give free rein to big business corporations.9

The impact of the conservative triumph has persisted through the Obama years, helping to galvanize an all-too-often frenzied right (and intimidate would-be liberals) on the issue of opposing Obama’s presumed “socialism.”10 Of course, there is nothing socialist about the policies of the Obama presidency; Obama is opposed, as have been all U.S, presidents, to the essence of socialism: the social ownership and democratic control of the economy, and its utilization to meet the needs of all people in society. Nor does he appear to be motivated by the principle enunciated by Karl Marx that “the free development of each would be the condition for the free development of all.”11 Obama’s orientation tacks significantly rightward from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s policies. Like Roosevelt, he is an unapologetic partisan of the capitalist system. Unlike Roosevelt, however, he has not chosen to advance significant efforts either to regulate the market or to put forward a far-reaching program of social reforms beneficial to America’s working-class majority.

The Radicalism of the Civil Rights Movement

Genuine socialists have played a substantial role in helping to shape the history of the United States, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s. The present study will demonstrate that those leading what was often referred to as “the Civil Rights Revolution” had a socialist orientation. This is glossed over in popular accounts of the movement. The fact is that the civil rights movement would not have been successful without the active involvement of conscious and organized socialists.

Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, in her magnificent survey of the scholarship covering the complex and multifaceted story of what she calls the “long civil rights movement,” has noted that both conservative and liberal defenders of the social-economic-political status quo have done much to dilute and “sanitize” what really happened. Martin Luther King Jr. is presented as “this narrative’s defining figure—frozen in 1963, proclaiming ‘I have a dream’ during the march on the Mall.” Selective quotes, repeated over and over and over, result in his message losing its “political bite”:

We hear little of the King who believed that “the racial issue that we confront in America is not a sectional but a national problem” and who attacked segregation in the urban North. Erased altogether is the King who opposed the Vietnam War and linked racism at home to militarism and imperialism abroad. Gone is King the democratic socialist who advocated unionization, planned the Poor People’s Campaign, and was assassinated in 1968 while supporting a sanitation workers’ strike.

Hall by no means calls for a simplistically radical counter-narrative, but she does insist on truthful accounts of what was felt, thought, advocated, and struggled for by activists who won and lost the various battles that made up the movement’s history. If there is a bias in what she argues for, it is that those telling the stories of the civil rights movement be true to what these magnificent human beings were actually about. “Both the victories and the reversals call us to action, as citizens and as historians with powerful stories to tell,” she concludes. “Both are part of a long and ongoing civil rights movement. Both can help us imagine—for our own times—a new way of life, a continuing revolution.”12

This spirit informs our effort in this book to utilize the Freedom Budget for All Americans as a prism through which to gain a useful perspective on the history of the civil rights movement, as well as the history of the United States—and maybe its future.

The Freedom Budget that was advocated from 1966 to 1968 was explicitly not a program for socialism. However, it was developed and advanced most effectively by socialists. It was seen by them as not only promising a realization of civil rights goals and of improvements in the quality of life for all Americans but also as a pathway that could help lead to a democratic socialist transformation of U.S. society.

The Freedom Budget could be seen as an expansion of the social-liberal orientation of the New Deal, and some of its supporters (and its critics) certainly saw it in that way. Yet there are some on the right as well as the left who would argue that just as capitalism necessarily involves the exploitation of labor in order to generate wealth, so will society-wide efforts to overcome poverty and inequality necessarily damage a system that requires a certain level of unemployment, or “reserve army of labor,” and cannot do without periodic devastating economic downturns to ensure the health of the market economy.13 The Freedom Budget had the potential, however, to seem quite reasonable and desirable to masses of people living in capitalist America. A popularly supported Freedom Budget, if it turns out capitalism cannot accommodate it, could have revolutionary implications, if the capitalist system proved incapable of realizing such reasonable, desirable goals and projections.

One key to understanding what happened in the victories and defeats of the civil rights movement has to do with the questions of organization and leadership....