![]()

PART I

CAPITALIST GLOBALIZATION

![]()

1—The Internationalization of Production and Its Consequences

We live in a time marked by growing international and national imbalances, instabilities, and inequities. What is not well understood is the connection between these threats to our well-being and contemporary capitalist dynamics.

Capitalism is not a static system. The levers driving its motion are capital accumulation, competition, and class struggle. Their complex interplay generates pressures and contradictions that compel profit-seeking capitalists to continually reorganize their activities, a process that has profound consequences for our lives. In other words, our social condition is largely shaped by the actions of the leading business organizations.

Today, these business organizations are transnational corporations. As we shall see, their drive for profit has produced a new, more globalized stage of world capitalism, one shaped by dynamics that are directly responsible for generating the imbalances, instabilities, and inequities that threaten our well-being. Most important, this means that the economic and social challenges we face have deep structural underpinnings. As a consequence, efforts at reform that accept the logic of existing patterns of economic activity will prove unable to satisfy our pressing need for meaningful social change.

The Growth and Transformation of International Production

Transnational corporations (TNCs) are more than just large companies with a global reach. They now direct a significant share of global economic activity. According to the World Investment Report 2011, “TNCs worldwide, in their operations both at home and abroad, generated value added of approximately $16 trillion in 2010, accounting for more than a quarter of global GDP. In 2010, foreign affiliates accounted for more than one-tenth of global GDP and one-third of world exports.”1

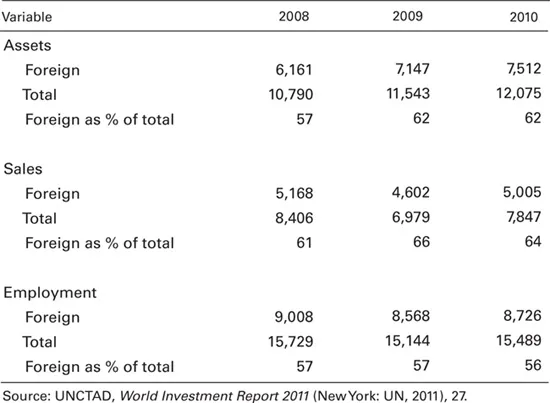

Transnational corporations tend to be among the largest and most powerful firms in their respective home countries. At the same time, as Table 1.1 shows, international operations now account for the majority of the assets, sales, and employment of the 100 largest non-financial TNCs. Looking at all TNCs, the value added by their foreign affiliates rose from approximately 35 percent of total value added in 2005 to 40 percent in 2010.2

The current centrality and internationalization of transnational corporate production is the result of a long and competitive process.3 In broad-brush, foreign direct investment (FDI) in the first decades after the Second World War was primarily motivated by the desire of transnational corporations to gain access to foreign markets protected by high tariffs. U.S. TNCs were the primary international investors during this period. Although important, these newly established foreign operations were generally viewed by their parent companies as supplementary to their home country investments.4

The motivation for, and nature of, foreign direct investment began to change in the late 1960s. In response to a growing decline in profit margins caused by the combination of increasingly successful Japanese and European export activity aimed at the U.S. market and rising domestic wages, U.S. transnational corporations began establishing “export platforms” in select third world countries. Parts and components were sent to these export platforms; low-wage third world workers performed operations on them; and the intermediate products were shipped back to the United States for final assembly and sale. Although these foreign operations were limited to relatively simple labor-intensive tasks, their activities were integral to home-country operations and profitability.

TABLE 1.1: Internationalization Statistics of the 100 Largest Non-Financial TNCs (bns of dollars, thousands of employees, and pcnt.)

The mid-1980s marked the start of the third and current stage in the internationalization of production, one marked by a sharp acceleration in foreign direct investment. Foreign direct investment grew far more rapidly in the 1980s than world trade and world output, “increasingly becoming an engine of growth in the world economy.”5 Between 1983 and 1989, world foreign direct investment outflows grew at a compound annual growth rate of 28.9 percent, compared with a compound annual growth rate of 9.4 percent for world exports and 7.8 percent for world gross domestic product.6

Again, this development was primarily the result of intensified competition between U.S. corporations and those from Japan and Germany. More Japanese and German exports to the United States gave these foreign corporations an ever larger share of the U.S. market, especially in higher-value-added manufactures, producing, among other things, a rapidly increasing U.S. trade deficit. Negotiations between the U.S., Japanese, and German governments aimed at reducing this deficit culminated in the 1985 Plaza Accord, which called for a significant increase in the value of Japanese and German currencies relative to the dollar. This outcome stimulated companies from both countries, especially Japan, to shift selected core operations to countries with more favorable currency rates and labor costs. East Asia was an especially attractive location for Japanese TNCs.7

Thus, while U.S. corporations had been the primary drivers of the internationalization of production until the mid-1980s, after that period TNCs from other countries began aggressively pursuing their own international strategies.8 In fact, outflows of foreign direct investment from Japan exceeded those from the United States beginning in 1986. In 1989 Japan became the largest source country of foreign direct investment flows, accounting for 23 percent of the total FDI outflows that year.9

This new stage was also marked by a change in TNC accumulation dynamics. Previously, transnational corporations had used export platforms to cheapen the production cost of labor-intensive and technologically simple goods such as garments and basic consumer electronics. The transnational corporate investment that began in the mid-1980s was undertaken to produce far more sophisticated manufactures. By the 1990s, these goods included automobiles, televisions, computers, power and machine tools, cameras, cell phones, pharmaceuticals, and semiconductors.

More important, the change in product line was coupled with a major restructuring in the organization of production. In brief, TNCs began dividing their production processes into ever finer segments, both vertical and horizontal, and locating the separate stages in two or more countries, creating what are commonly called cross-border production networks or global value chains. The Asian Development Bank offered the following description of the change:

In its formative years in the early 1990s, production sharing involved moving small fragments of the manufacturing process to low-cost countries and importing their component outputs to the host country for the last-stage fabrication.

Later, production networks became more intricate, with firms in different countries having charge of different stages of production, thus resulting in product fragments crossing multiple borders prior to final product assembly in the host country. More recently, with international supply networks of parts and components now well established, firms have also started setting up final-assembly processes for a broad range of consumer durables (such as computers, cameras, televisions, and automobiles) abroad, both to take advantage of cheap labor and to be closer and more responsive to niche markets.

Today, cross-border trade in parts and components has developed into a truly global phenomenon, although it plays a far more important role for developing Asia than for other developing regions, given the region’s integration with the world economy. Particularly with the emergence of the PRC [People’s Republic of China] as the premier final-assembly center of electronics and related products since the mid-1990s, intraregional flows of both parts and components and final goods have recorded phenomenal growth.10

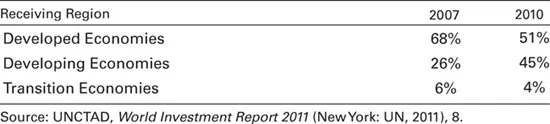

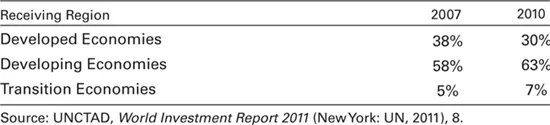

The adoption of this new transnational corporate strategy greatly increased the importance of the third world as a location for international production. As a consequence, the third world share of world foreign direct investment began a slow and steady rise in the late 1980s. The current centrality of the third world to transnational production is highlighted by the fact that in 2010, for the first time, more than half of all FDI went to third world and transition economies.11 As Tables 1.2a and 1.2b show, this outcome is the result of developed as well as developing and transition country TNCs shifting their investment activity to the third world.

Although core country TNC dominance of cross-border production networks remains strong, international competitiveness pressures have led to a constant process of change in their organizational structure. In particular, many core country TNCs have come to rely on independent “partner” manufacturers to procure required parts and components and oversee their assembly into final products. Some, but not all, of these partner manufacturers are themselves transnational in their operation. In many cases, these partner TNCs are headquartered in the third world. One consequence of this development: a growing number of core country transnational corporations are no longer directly involved in production. Rather they maintain control over their production networks through their control over product design and marketing.

The most common non-equity modes (NEM) of transnational corporate control and coordination are contract manufacturing, services outsourcing, contract farming, franchising, licensing, and management contracts. Firms operating under NEM arrangements employed approximately 20 million workers and generated over $2 trillion in sales in 2010, with contract manufacturing and services outsourcing by far the most important.12

Although the use of NEM-organized production varies considerably across industries, it is especially important in those with significant labor-intensive operations. For example, contract manufacturing activity accounts for an estimated 90 percent of the production cost of toys and sporting goods, 80 percent of the production cost of consumer electronics, 60 to 70 percent of the production cost of automotive components, and 40 percent of the production cost of generic pharmaceuticals.13 And, not surprisingly given the export emphasis of cross-border production, in 2010 contract manufacturers accounted for more than 50 percent of world exports of toys, footwear, garments, and electronics.14 Moreover, there is every reason to believe that TNC reliance on NEM-structured activity will become even more important in the future; the growth of NEM sales over the years 2005 to 2010 outpaced the growth of overall industry sales in electronics, pharmaceuticals, footwear, retail, toys, and garments.15

TABLE 1.2a: Distribution of FDI Projects by Developed Country TNCs

TABLE 1.2b: Distribution of FDI Projects by Developing and Transition Country TNCs

The nature of NEM-participating firms varies by industry. As the World Investment Report 2011 explained:

In technology and capital-intensive industries a small number of NEMs—often TNCs—dominate. In automotive components, pharmaceuticals and ITBPO [information technology and business process outsourcing] companies from developed countries are the largest contract manufacturers, while in electronics and semiconductors the situation is more mixed, but with developing country companies the more significant. In the case of labor-intensive industries such as garments, footwear and toys, however, a number of developing country TNCs act as intermediaries or agents between lead TNCs and NEMs, managing the manufacturing part of the GVC [global value chain].16

To the extent that participating firms are not themselves transnational, it means that TNC dominance over international economic activity is greater than previously stated. And to the extent that these firms are themselves transnational, it means that contemporary capitalist accumulation dynamics have given rise to a hierarchically structured, interlocking system of TNCs.

Case Study: The Electronics Industry

The electronics industry, which is one of the most reliant on this new form of international production, provides an excellent illustration of its workings. According to the World Investment Report 2011:

Contract manufacturing in the electronics industry evolved early. Offshoring up to the mid-1980s took the form of manufacturing FDI, as TNCs took advantage of cheaper, relatively skilled labor in host countries to process and assemble intermediate goods for shipping back to their home economies. In the latter part of the 1980s, a number of electronics companies started shedding manufacturing operations to concentrate on R&D, product design and brand management. The manufacturing was taken up by electronics manufacturing services (EMS) companies, including Celestica, Flextronics and Foxconn. Some of these emerged from existing suppliers, especially those based in Taiwan Province of China (e.g. Foxconn); others were spinoffs, such as Celestica from IBM.

A small number of contract manufacturers now dominate the industry, with the largest 10 by sales accounting for some two-thirds of the EMS activity. They produce for all major brands in the industry, from Dell and Hewlett-Packard in computing to Apple, Sony and Philips in consumer electronics, with overall sales in electronics contract manufacturing amounting to $230–$240 billion in 2010.

All but three of the top 10 players in electronics contract manufacturing are headquartered in developing East Asia—the bulk of manufacturin...