![]()

CHAPTER ONE

SPACE AS HISTORY

Both collective memory and collective identity are the effects of inter-subjective practices of signification, neither given nor fixed but constantly re-created within the framework of marginally contestable rules for discourse.

—JONATHAN BOYARIN

People without wants are poor.

—HONORÉ DE BALZAC

HELL’S KITCHEN

IN HIS HISTORICAL SKETCH of New York City’s Middle West Side, written in 1912, social worker Otho Cartwright describes not only the character of the district, but, as important, how the district was perceived by outsiders:

The district of which we write has been known for many years as the scene of disorders, of disregard of property rights and public peace. Certain it is that in the minds of New Yorkers who live outside the district … as well as in the minds of the police authorities, there still lingers a tendency and doubtless a liking to think and speak of the district by the nickname that disorders, rioting, and crime won for it in the early days of its settlement, namely “Hell’s Kitchen.”2

Referring to the residents of the area and their perceived apathy, Cartwright grimly quotes the French writer, Balzac: “People without wants are poor.” From his perspective as a social worker at the Bureau of Social Research, Cartwright surveyed a district of “disheartening inertia,” “social neglect,” and a population that had, in his words, “accepted the conditions of their environment.”3

As a foot soldier at the cutting edge of the Progressive movement, Cartwright, like many of his contemporaries, tended to emphasize the worst aspects of his objects of study, and to analyze them in terms of physical environment.4 Working for reform organizations that were, in large part, funded by private interests, these Progressives, armed with clipboards, surveys, and the latest social theory, set out to catalogue the quantitative and qualitative conditions of the urban poor. Their work, while problematic, has left a valuable archive by which to evaluate the history of urban America during the Progressive Era. As Cartwright and other social workers demonstrated, the Middle West Side was certainly a district with more than its share of urban problems. But by 1912 it was also, like many other areas of Manhattan, part of the great experimental laboratory of the Progressive movement. Participating in what the urban historian Stanley Schultz has dubbed “the gospel of moral environmentalism,”5 Progressives like Cartwright used their statistical and narrative evidence to advocate for changes in the built environment in areas like Hell’s Kitchen. For these Progressives, providing the poor with the proper living environment was seen as the surefire cure for the ills of urban communities whose development had resulted from the demands of the private market. Attempts to ameliorate these conditions took a variety of forms. From the creation, in 1884, of the New York City Tenement House Commission, to the formation of the West Side Improvement Association in 1907, Hell’s Kitchen6 had been subject to spatial restructuring projects brought about, in part, through the efforts of Progressive reformers. The passage of tenement laws, new park and bathhouse construction, dock repairs, the locating of settlement houses, and street cleaning were just some of the projects carried out between 1894 and 1914 to provide a proper environment for the residents of the Middle West Side. It was hoped that, as social worker Katherine Anthony explained, “the appearance of respectability would create the desire for respectability” among the “less ambitious” West Side residents.7

The spatial archive: a tenement with business on the ground floor. Note Ben-Hur Stables in background. (Milstein Division of United States History, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations)

Cartwright’s “people without wants” occupied the area from Seventh Avenue to the Hudson River,8 bounded on the south by Thirty-fourth Street and on the north, according to most sources, by 54th Street.9 Known from the Dutch period as the Great Kill District,10 it was a mixture of hilly forest, swampland, and streams, the largest of which gave the district its early moniker. The undesirability of much of the landscape for residential development, as well as the district’s proximity to the Hudson River waterfront, has linked its developmental history to industry, shipping, and manufacturing, which greatly contributed to its reputation as “dingy and noxious.”11 By the late nineteenth century, the area was dominated by low-lying factories, warehouses, stables, and piers west of Tenth Avenue, and by tenement apartments of the “dumbbell” or “railroad” type east to Broadway. Indeed, as Cartwright states, “From an architectural standpoint the district has neither salient features nor real uniformity.”12 Though Cartwright places much of the blame for this state of affairs on the “lack of a proper building plan,” city planning itself is partly responsible for the perceived lack of character. As urban historians Hendrik Hartog, Jon Teaford, and others have demonstrated, New York City was part of the municipal revolution of the nineteenth century, as the city government took an increasing role in providing street plans, construction, transportation infrastructure, and other services, in combination with the state of New York.13 The monotony and lack of “quaintness or color” that Cartwright bemoans were as much the result of New York’s grid plan of 1811 and the uneven level of street repair, coupled with the provisioning of elevated railways meant to spur development and population, as they are the result of the dominance of private interests and the chaotic development of unregulated capitalism.

Far from being the result of a lack of planning, the spatial environment of the Middle West Side was the result of competing interests with differing views of the value of space. Proximity to the waterfront made the area prime space for certain industries. Tenement landlords and the system of subleasing produced an inadequate and often unsafe housing stock.14 City and state government directed resources to the creation of the parks that framed the area (Central and Riverside), while neglecting to provision the less politically influential residents of the Middle West Side with open space and the real estate value it creates in its wake. Reformers utilized statistical studies and the latest in social theory to demand the construction of playgrounds and bathhouses, as well as rules governing the form of tenements. And of course, the residents and merchants of the area turned the space of the Middle West Side into the places of their daily rounds. Thus while one must pay strict attention to the dominant mode of spatial practice, the demands of a capitalist economy, critical geography also realizes that space at the level of the urban scale is, in the words of Edward Soja, “a multilayered geography of socially created and differentiated nodal regions nesting at many different scales around the mobile spaces of the human body and the more fixed communal locales of human settlements.”15 Though the actual built environment is the result of spatial practices of power and domination, the production of space is something quite different. Thus while it remains true that the records of the deeds of Progressives form a valuable historical archive of the period, the built environment itself, the space of daily life, may indeed tell us more about both the reformers and the population they intended to reform.

The occupants of the tenements of the Middle West Side at the turn of the century were, unlike their more colorful and well-studied new immigrant neighbors of the Lower East Side, nearly evenly split between foreign born and those born in the United States. They were predominantly “white,” and predominantly descended from parents of Irish and German origin. Many of the Irish families had arrived as part of the famine migrations of the 1850s and 1879, and many German families descended from those arriving during the great wave of German immigration between 1817 and 1853. Many of these families had lived on the Middle West Side for several generations by 1900, and were joined by new Irish and German arrivals seeking work on the waterfront. These two ethnic groups dominated the local population, but by the turn of the century they were joined by smaller clusters of new immigrants and shared space with, among others, small pockets of Jews, African Americans, and Anglo-Saxon “natives.” As with most urban neighborhoods, residents were drawn to their own ethnic and racial cohorts, with clusters centered in church parishes, divisions that often resulted in open violence, but there were also numerous examples of interethnic cooperation on the Middle West Side. Residents shared the common experiences of economic insecurity, lack of social services, and being commonly perceived by outsiders as dangerous, and the area was widely known by the city’s middle and upper classes as one to avoid. Perhaps the most commonly shared experience was the lack of respect Middle West Side residents received from city authorities, a phenomenon that had strong, if rare and brief, unifying effects.

Far from being a population without wants, residents of the Middle West Side make up a fractious but coherent community whose individual and collective wants were structured and contained by the physical environment of their neighborhoods and their own place as a community within the processes of uneven geographic development that shaped the built environment. Operating within what geographer Richard Peete terms the “daily prism” of segregated locational scales, Middle West Side residents formed their wants within a specific framework of spatially determined action. Those actions were framed by the historically contingent spatial conditions of the area, where, by 1900, 230,000 of the 270,000 residents lived in buildings officially classified as tenements. Further, residents made their daily rounds in an area where a lack of regulation had led to mixed-use development, with tenements often abutting factories and waste drainage sites for the runoff from slaughterhouses.16 As mentioned, Hell’s Kitchen had garnered a reputation as both slum and red-light district, leading to negative conceptions of residents by outsiders and city officials. As a result, residents expressed a deep dissatisfaction with city services, and a deep distrust of city officials, particularly police officers. These officials returned the sentiment, often viewing residents of “the Kitchen” as criminals. As sociologists John Logan and Harvey Molotch point out, “Location establishes a special collective interest among individuals.”17

As well, Progressive reformers who encouraged city residents to demand efficient service from their municipal government shaped wants in the form of political demands. Many reformers saw the relationship between built environment and human behavior as direct and unambiguous.18 Trained by men like the social theorist Simon Patten, they were deeply influenced by European ideas regarding city planning and proper physical environment. Progressive social workers, particularly after 1900, turned increasingly from focusing on the morals of the urban poor to an emphasis on the scientific basis of poverty. Seeing the built environment as a key to combating entrenched poverty, many Progressives not only advocated for improved physical conditions, but also sought to form a public among the urban poor that would demand improvements of city authorities. Seizing the opportunity provided by the perception among the public that big business needed to be regulated and that party politics was deeply corrupted, these reformers used their positions as experts to promote spatial restructuring and encourage urban citizens to participate in the daily running of the city. They believed that even the urban poor, provided with the proper tools and space, could become “rational citizens,” and form what New York Bureau of Municipal Research founding member Frederick Cleveland dubbed “a socialism of intelligence.”19

For the residents of the Middle West Side, wants were further contained and promoted by the structural conditions at the level of local, city, state, and federal government, which all contributed to the spatial restructuring of the district. The period under investigation, 1894 to 1914, is one in which the government at all levels steadily increased its activities in the areas of social provision, infrastructure improvement, and the regulation of immigration.20 Government at all levels increased in its ability to regulate the private marketplace, as seen in the battles with developers over housing, utilities, and transportation, and in larger battles over monopoly control of economic sectors. The period also saw the rise of reform at the local and state level, as politicians increasingly forged partnerships with nongovernmental Progressive groups, bearing the mantle of reformers whether they were connected to machines or not.21 The attacks on patronage and on the political party structure, part of the attempt to create a rational public sphere, produced new political formations, such as fusion candidates and independent commissions whose goals were to break the power of localized party political organizations. These changing political circumstances greatly affected the process of spatial restructuring and the attitudes of residents toward government at all levels.

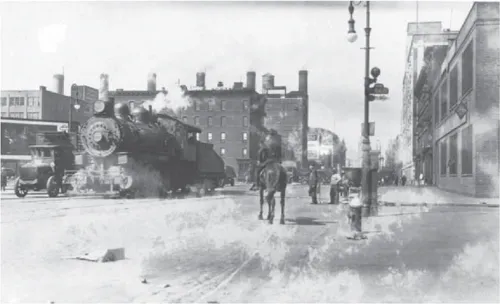

Steam engine on Eleventh Avenue, running through one of the most crowded neighborhoods in the city. (Milstein Division of United States History, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations)

What we are interested in, then, is directly concerned with measuring the effects of such spatial restructuring on the residents of Manhattan’s Middle West Side in the period between 1894 and 1914. Spatial restructuring is defined here as changes in the built environment brought about through the combination of private market interests, government agencies, and reform organizations. The main question we address is, how does the restructuring of physical space affect human activity? We attempt to answer the question through an examination of the processes of uneven geographic development and the production of space.22 We aim, first, to achieve a deeper understanding of how the physical built environment structures urban life, and second, to find an adequate way to understand the particular spatial history of the period under study. In the case of the former, there is little dispute as to the importance of the built environment in urban history. But what is less accepted is how space itself acts in the process of structuring urban political alliances. As to the latter question, linking changes in the built environment to the concept of the production of space opens new opportunities not only for understanding the history of urban development during the Progressive Era, but can be usefully applied to contemporary issues, such as disputes over school district boundaries and localized secession movements.

The Ninth Avenue elevated train ran through Hell’s Kitchen. Until 1902, steam trains ran on the line, dropping hot ash on pedestrians below. (George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

Making the connection between space and urban politics requires not only examining how space is produced, but also the “difficult prospect” that such a process of production is, as anthropologist and Marxist geographer David Harvey suggests, “constitutive of the very standards of social justice used to evaluate and modify” its use and subsequent alteration.23 In other words, how does the spatial environment produce the very discourse that is used to guide, direct, and control spatial restructuring and what effect does this discourse have on residents? This suggests that the very process of spatial restructuring and the decisions that guide such a process are framed within a language that is produced by perceptions and conceptions of the space itself. When city planners and government officials make decisions about where to invest in urban restructuring, they are influenced by their preconceived ideas about the physical space and its inhabitants. Coded descriptive language, such as dangerous, pleasant, blighted, up-and-coming, struggling, bedroom community, concern not just the area but is seen as descriptive of residents as well, serving to produce perceptions that then govern decisions of future investment. Aside from affecting investment decisions, these codes also play a role in the formation of the self-conception of residents, particularly in their relationships with authority and with notions of citizenship. In this book we will be examining the contradictory ways that technologies of control deployed by reformers and government attempt to shape a temporal horizon for residents that is then weighed down and reinterpreted within the spatial order. In order to begin answering this difficult question concerning the relationship between space and citizenship, it is necessary to turn to theories of spatial ontology to uncover the role of spatial restructuring in the formation of conceptions of citizenship.

UNEVEN GEOGRAPHIC DEVELOPMENT

“UNEVEN GEOGRAPHIC DEVELOPMENT is a concept deserving of the closest elaboration and attention,” states David Harvey.24 For Harvey, uneven geographic development concerns the “production of spatial scale” and the “production of geographical difference,”25 with both components interacting to produce space and reproduce social relations. But as Harvey points out, “relevant scales” are never produced outside of the natural components or influences that structure all human geographic alteration. Scale here refers to the human understanding of space and terrain, how we order things in space at different levels, such as neighborhood, city, region, and state, to name just a few. Our understanding of the scalar processes of the production of urban space must first include an analysis of the relation of the natural contours and terrain to the construction of the built environment. For New York City’s Middle West Side, proximity to the Hudson River, as well as the original swampy conditions of the area made it a less than ideal location for upscale residential development, and subs...