![]()

1. The Calm before the Storm

The economic outlook continues to be favorable.

—HENRY PAULSON, 2005

Just three years ago, in the spring of 2006, things appeared very promising. The home construction industry boomed, absorbing those looking for work and those waiting for jobs to open up and pushing down the rate of unemployment. For all of 2006, the official unemployment rate was 4.7 percent, and in the spring of that year it was about 4.4 percent. Both numbers were low by U.S. standards. Wages were rising. The Bush administration saw the numbers as justifying its economic polices: “Today’s strong report shows that our economy continues to produce steady, sustainable employment growth with strong wage gains for America’s workers. Average hourly earnings for workers jumped 4.2 percent in 2006, the best 12-month showing since 2000,” U.S. Secretary of Labor Elaine L. Chao said in a public statement on January 5, 2007. “This is further evidence that the president’s economic policies are working and producing strong wage gains for America’s workers, and we should be cautious of future policies that would slow these gains.”1 Some of the money from the real estate explosion found its way into the stock market, and the most famous stock index, the Dow Jones, hit an all-time high in October 2007.

It should be expected that the president and his staff would take good economic numbers at face value and milk them for political advantage. But economists and financial experts were no different. With few exceptions, they saw a bright future. There might be some bumps in the road, but severe downturns were things of the past, of only historical interest. They believed that money managers in the world’s financial centers had harnessed the techniques of advanced mathematics and statistics and learned how to handle risk. Financial markets, so they told us, acted as stabilizers, preventing too much euphoria on the upside and too much pessimism on the downside. If an unexpected sequence of events occurred that threatened prosperity, the Federal Reserve could put things right by loosening or tightening the credit strings. “Trust in the markets,” said the economists and financiers. And the Fed will take care of any market instabilities before they become crises. Pick an economist or financial wizard. Maybe Alan Greenspan, chairman of the Fed, who was worshipfully proclaimed to be both “oracle” and “maestro” of the economy. Perhaps Robert Rubin, President Clinton’s Secretary of the Treasury and wise man of Wall Street. Or Lawrence Summers, world-famous economist, another Clinton Treasury secretary, president of Harvard, and former chief economist at the World Bank. Were any of these luminaries warning us that—as we all now know and as left-wing economists writing in the pages of journals far removed from the mainstream, like Monthly Review, were telling us for many years—that the floorboards of the economy were rotten? That housing prices could not continue to rise at a rate far surpassing the growth of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP)? That it was not possible for Wall Street to post outlandish returns year in and year out? That increasing levels of consumer, corporate, and government debt—relative to the underlying economy—couldn’t go on forever? That the unimaginable growth of speculation, using ever more complex and risky ways to gamble, was inherently destabilizing? That an eternally expanding economy was as much a myth as the fountain of youth? Perhaps the most remarkable thing is that the housing bubble began almost immediately after the dot-com bubble burst. Yet few seemed to wonder how it could be that the new bubble wouldn’t also burst, sooner or later.

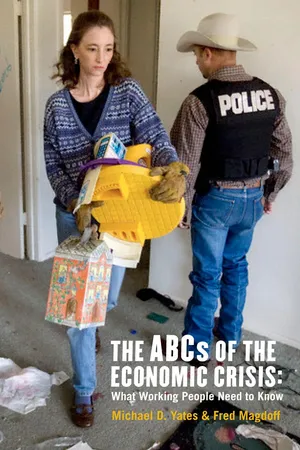

Now, a few years later, we are living in desperate times. Every day, thousands of workers lose their jobs. In June 2009, the United States official unemployment rate hit 9.5 percent, and it will get higher in the months to come.2 Housing prices are in free fall, and tens of millions of households are choking on debt. The titans of Wall Street have gone bankrupt or to Washington to beg for money. Colossal financial frauds have come to light, in which psychopaths like Bernard Madoff stole billions of dollars from gullible clients who thought it was their right to make high rates of returns on their money. On Main Street, tales of woe abound. A woman over ninety years old was duped by a bank into taking out a large mortgage she couldn’t possibly afford. Now she may soon be homeless, as will many other poor people, often minorities, who were swindled by unscrupulous lenders. Many home buyers may have made reckless decisions. They did not cause the crisis, however. As we will show, it was the often fraudulent actions of the banks and the big Wall Street firms that created the financial mess in which we now find ourselves.

Fourteen million, seven hundred thousand people were officially unemployed in June 2009, and this does not include the nine million working part-time involuntarily (because their work hours were cut or part-time employment was all they could find) and the 2.2 million people “marginally attached” to the labor force (they were not officially unemployed but wanted a job and had searched for one in the past year; of these, there were 793,000 “discouraged workers,” who had stopped looking for work because they believed no jobs were available). Adding these to the officially out of work raises the unemployment rate to 16.5 percent. Very troubling is that long-term unemployment (those out of work for at least fifteen weeks) is now at its highest level since the government began measuring it in 1948.3 States are running out of money for unemployment compensation. In January 2009, 50,000 New Yorkers were scheduled to exhaust their unemployment benefits after receiving them for eleven months. A New York Times reporter tells of “Julio Ponce, a 55-year-old chef, [who] has been using his weekly unemployment check to pay the rent on his apartment in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn since he lost his job at a center for the elderly more than a year ago. But he said he did not know how he would cover the $800 monthly rent after his unemployment benefits lapsed this week. ‘No one is helping me,’ said Mr. Ponce, who was faxing his résumé to hotels and restaurants from an employment office in Downtown Brooklyn on Thursday. ‘I’ve applied for public assistance, but I don’t think I’m going to get it.’”4 Nationwide, by March of 2009, about one-quarter of the unemployed had been out of work for at least six months and many were running out of unemployment benefits, having gone through the twenty-six weeks their states provide and more than thirty weeks of extended benefits mandated by the federal government. One economist estimated that in the second half of the year, 700,000 people would exhaust their benefits.5

Making matters worse, our nation’s unemployment compensation system is much less generous than it used to be. A lower percentage of workers receive unemployment insurance payments—only 37 percent are eligible, compared to the 50 percent during the recession in the mid-1970s. The maximum amount of time that people can receive unemployment payments has been reduced from sixty-five weeks to a standard of twenty-six weeks today, recently extended by Congress for an extra thirteen weeks (and still further in the stimulus package enacted by Congress in February of 2009). Furthermore, employers have become more aggressive in challenging unemployment claims, and many employees have discovered that they cannot collect the benefits to which they thought they were entitled. To stave off hunger, record numbers of people are seeking food stamps. At the beginning of April 2009, a record 32.2 million persons were receiving food stamp assistance, one in every ten Americans.6 In past downturns they would have sought public assistance as well. In the 1970s, over 80 percent of the poor were eligible to receive public assistance through welfare programs such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children. Now, after the welfare “reforms” of the Clinton era, only 40 percent of the poor are eligible to receive assistance.7

Beneath the harsh statistics, diligent journalists, social workers, police, and mental health counselors are witnessing more ominous responses to the crisis. Increases in murders of coworkers and family members, suicides, thefts, bank robberies, arson, domestic disturbances, depression—all have been linked to the growing hard economic times in towns and cities in every part of the country. The New York Times reports that anxiety and depression, triggered by the economic downturn, are on the rise, with more people seeking treatment from mental health professionals. In a Times/CBS poll, 70 percent of respondents were worried that a household member would be jobless. And as people become desperate after losing their jobs, robberies have become more common. There have even been a rash of thefts in California of the furnishings that companies place in houses to make them easier to sell, and sometimes even plumbing and other fixtures are for sale on the black market.8

There is no doubt that we are in the most severe economic crisis since the Great Depression. In 1982, when we were in a deep recession, unemployment was higher than it is now. But then the Federal Reserve (the government agency that tries to influence economic activity by making credit easier or more difficult to obtain) forced interest rates on loans to record-high levels in an effort to eliminate inflation and scare the daylights out of working men and women. High interest rates were also bad for companies who needed to borrow money, and they responded in 1982 with mass layoffs, further reducing demand and also making it less likely that workers would insist on higher wages in the near future. Once inflation was tamed, the Federal Reserve pushed interest rates down and the federal government pumped money into the economy through its own spending. Within a couple of years, the economy began to recover. Today, however, the Federal Reserve has managed to get interest rates as low as it can (some rates are near zero) yet still economic activity continues to decline and will probably stabilize at a low level. We have to go back to the 1930s for a precedent, or to Japan in the 1990s—when no amount of government intervention could get the economy rolling. Already our government has spent hundreds of billions of dollars and committed trillions more to trying to get banks to open their lending windows and consumers and businesses to start borrowing, but credit is still nearly frozen and spenders are retrenching. Mortgage rates are near record lows and gasoline prices have dropped dramatically, yet houses are not selling well and car sales have tanked to the point that even the world’s premier auto company, Toyota, is losing gobs of money and the weaker ones are essentially bankrupt—subsisting on government handouts. Nothing seems to be working.

What in the world has happened? We will explain in some detail what happened and why it happened. But for now, let’s just take the example of the housing market, mentioned above. It’s true that housing prices were at record highs and seemed like they would continue to increase. But the explosion in home building and the dramatic increase in home prices was partially a result of speculative buying: people kept purchasing houses because they thought prices would always rise. And as they kept buying, prices did continue to rise. It was like a Ponzi scheme in which someone promises large returns and pays these out to the first “investors” with the money hustled from later ones. Some house buyers, especially those involved early in the price escalation, cashed out and made a lot of money.

Every night on television you could tune in to a show in which savvy individuals bought houses, either fixed them up with minimal investment or not, and then “flipped” them for a much higher price. It looked like anyone willing to put in a small effort could get rich in real estate. In hot markets like Las Vegas, Southern California, and parts of Florida, home owners saw their houses double or even triple in price in a year or so. Condominiums sold two and three times before anyone moved into them. One of us was in Key West, Florida, in 2005 and saw shacks selling for a million dollars. And as house prices skyrocketed, their owners borrowed money against the appreciated value and used the money to buy more property, make additional home improvements, or purchase all manner of goods and services—helping to keep the economy going by using their homes as ATM machines.

But as we will see, the housing and mortgage market was truly a house of cards, built on low interest rates, easy money, the pushing of purchases on people who couldn’t afford them, speculative fever, and the use of fraudulent tactics and misleading mortgage terms. And once a significant number of people were unable to make their mortgage payments, it became clear there was a problem. Homes offered for sale started to swamp purchases and prices fell. The falling prices forced the more indebted home owners and some speculators to sell, pushing prices down further. The bubble burst. And this was only one of the many symptoms that a major crisis that was brewing.

Today, in the spring of 2009, after more than a year of cataclysmic economic occurrences, those who should know still don’t have a clue as to what actually happened or why it occurred. In congressional hearings on October 23, 2008, Representative Henry Waxman asked Mr. Greenspan, “In other words, you found that your view of the world, your ideology was not right. It was not working.” The maestro replied, “Precisely. That’s precisely the reason I was shocked, because I had been going for forty years or more with very considerable evidence that it was working exceptionally well.... I still do not fully understand why it [the crisis] happened.”9

Economist Jeff Madrick, a sharp critic of his mainstream colleagues, attended the December 2008 annual meeting of the American Economic Association in San Francisco and found that no one took any blame for failing to foresee what was happening. No one suggested that something must be wrong with a discipline that had no idea that a very severe recession, or a possible depression, was striking, fast and without mercy.10 The irony is that some of the very same people whose heads were in the sand—except when they were up and about sniffing for easy money to be made—are now in charge of the government’s unprecedented bailout. No wonder the people are up in arms.

So, then, we have an economy sailing along, poised, it seemed, for even better things to come, and all of a sudden the wheels fall off the bus. The economists and financiers can’t tell us what happened or why it happened. Their training doesn’t seem to have prepared them for this.11 If ever there was a time when the emperor had no clothes, it is now. What are we to do in such circumstances? Was it all a big accident? Were evil men and women conspiring to ruin the economy, while they enriched themselves? Was it Bush’s fault? Clinton’s? Greenspan’s? Here are some good starting suggestions for those of you who want to find out. Ignore what you see on television. Don’t listen to or read the commentaries of mainstream economists. Hide your wallet when bankers or Wall Street bigwigs put forth their two cents. Assume that when government spokespersons are at the podium that they are either lying or ignorant of the truth. And most important, Read on!

![]()

2. What Makes Capitalism Tick?

Accumulate! Accumulate! That is Moses and the Prophets.

—KARL MARX, 1867

A working person toiling away on an automobile assembly line or in a restaurant kitchen must have found it difficult to understand how the bankers and brokers who have brought the economy to its knees made so much money simply by selling pieces of paper. If workers make cars, houses, or meals or teach children, and when farmers produce food, they are producing something that people need and can use. But those who sell complex financial instruments don’t produce anything tangible at all. Something doesn’t seem right about making money without producing a useful good or service. And indeed, no society can survive if the only economic activity—or even the dominant activity—is lending and borrowing money. The same can be said for buying already-made things at one price and selling them at a higher price. If the only economic activity is merchant trade, everyone will soon die because nothing is being produced. At its most fundamental level, an economy is a system of production of at least some useful outputs. When so much labor is devoted to the buying and selling of pieces of paper, with the sole aim of converting money into money, something profoundly irrational is taking place.

Every society must organize its land, raw materials, tools, and labor (together these are called the means of production) so that when combined, food, clothing, and shelter are brought into being. For most of our time on earth we organized our small societies collectively to produce things and shared what we made in a roughly equal way. We no longer do this, but we still produce, as we must. Our system of production is called capitalism, and inside it, a relatively small number of people, called capitalists, control the organization of the means of production—through their ownership of everything but the labor—with the aim of getting the output made in such a way that they make as much money as possible. The way it works is pretty simple.12 The majority of people do not own enough land, materials, and the like to produce what they need for themselves. So they must sell the one thing they do have—their ability to work—to the owners of businesses. Once sold, our labor becomes the property of our employers. Since most of us have no alternative way to survive except to work for somebody, we enter into a profoundly unequal relationship with our employers, one that allows them to organize production to their advantage. They are able to compel us to work a number of hours and in su...