![]()

1. Beginnings

In the wake of the United Automobile Workers’(UAW) historic victory early in 1937 over the vast General Motors Corporation, change filled the air in the United States, and a resurrection of union organizing efforts surged across the country. Even in the model town of Hershey, Pennsylvania, the rush to organize erupted so quickly that local workers formed a union before the Congress of Industrial Organizations could develop a jurisdictional division for them, and the union became known simply as Chocolate Workers of America Local 1, CIO.1 On March 2, United States Steel recognized the Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC) as representative of their employees, and elsewhere workers sought to “come join the CIO,” as the song of the day entreated. In Erie, the CIO’s United Rubber Workers of America (URW) Local 61 gained a foothold at Continental Rubber and URW Local 72 organized Lovell Manufacturing; and, after years of disappointment in trying to gain support from the American Federation of Labor’s Machinists’ union (IAM), Erie steel workers turned to SWOC and won charters in March and April through the efforts of rank-and-filers and organizers Paul Nunes and Earl Long.2

Organizing six thousand electrical manufacturing workers at General Electric’s giant Erie Works, however, promised to be more complicated than taking on hundreds of rubber workers. Besides, the great victories that are so well remembered among labor activists and friends today were accompanied by defeats in other Pennsylvania towns, such as Hershey, Johnstown, and Aliquippa, where vigilantes joined corporate loyalists in attacking workers and organizers. Accordingly, the effort at GE began cautiously. About fifty people attended the first public organizing meeting at Nagorski Hall on a sunny Sunday, May 3, 1937. Of those, twelve signed up and paid their two-dollar initiation fee, and the temporary officers forked up another six dollars to pay the fees of three others so that the group could attain the fifteen-member minimum needed to qualify for a charter from the infant United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America. That completed, UE 506 soon received its charter from the union’s vice president, August Hein of Buffalo. The work of organizing then began in the shadow of the infamous Battle of the Overpass when forty Ford Motor Company thugs beat up Walter Reuther and other UAW partisans on public property in Dearborn, Michigan, on May 26, and the Memorial Day Massacre of ten strikers, many shot in the back by Chicago policemen, at Republic Steel in South Chicago, Illinois.3

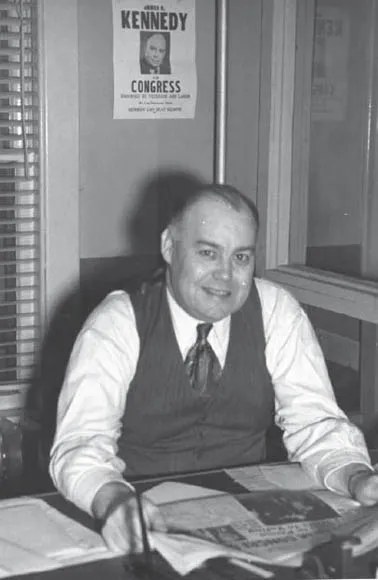

Jim Kennedy, first president and first business agent.

Jim Kennedy, a bricklayer in the Building and Maintenance Division, led the local. Like many other leaders over the union’s history, Kennedy came from a strong union family, and he impressed fellow workers with his sincerity and his integrity. Politically, Kennedy was “something of an old socialist” according to fellow activists, a left-wing New Deal supporter who had spent two years at Duquesne College in Pittsburgh. Because his job duties carried Kennedy to many areas of the plant, his organizing opportunities multiplied, as did the worksite mobility of Clara Williamson, a plant janitress, equipment officer Bill MacMillen, and grounds crewman Everett “Fats” Whipple.4

One of Kennedy’s early recruits was Bill Winn, an Englishman with a union past in his homeland who had experience in GE’s company union, the GE Industrial Union, with which the corporation hoped to head off genuine workers’ unions. Winn had served as a divisional representative to the company union’s Works Council, which the Englishman found congenial though ineffective in dealing with workers’ real needs. Moreover, Winn’s experience at GE by now included a demotion from assistant foreman in the Transformer Division, which the company had moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, to line work in the recently constituted Refrigeration Division at reduced wages and under the supervision of an Italian hard-nosed “straw boss” of a foreman, a circumstance that irked the Anglo-American even further. Winn also reacted strongly against the favoritism and arbitrary authority that he witnessed with regularity. When Kennedy called, Winn was ready.5

The company’s tactic of keeping its skilled people, such as Winn, by providing them a job—any job—during depressed economic times seems in this case to have backfired. Bill Winn felt resentment, not gratitude, because of his position under the foreman, and he soon emerged as a leader of the UE organizing effort, doubling for a time as the local’s vice president and as chief steward of the Refrigeration Division. A similar sequence of events marks the path of Artie McCullough, a skilled ball bearing expert. Like Winn, McCullough had experienced both the inadequacies of working within the company union and the trauma of transfer to an unskilled rating in Refrigeration. Like Kennedy and Winn, McCullough was a man in his middle years. A younger man, the screw machine operator Roy Christoph—son of a Socialist Party metal polisher—had given the company union a try, too, but joined UE and would serve later as president of UE Local 618 and of the Erie area’s Industrial Union Council.6

Other UE activists illustrate both the diversity and the commonality of backgrounds and aims in the coalitions that assured the success of the many union organizing campaigns of that era. A disproportionate share of elected leaders at the Erie GE plant came from “old stock” (northern European) ethnic backgrounds or were, like Winn and Louis E. Nicholson, persons of previous union involvement, or were established workers. Women activists were few, but included Clara Williamson, Mary Kuyler, and Beatrice Wise.

During the local’s earliest years, immigrant and second-generation Italians and Poles were also active, if underrepresented in elected leadership positions. Among the temporary officers elected at Nagorski Hall, sergeant-at-arms Ignatius Piatkowski sat beside Kennedy, Winn, Recording Secretary Thomas McCarthy, Treasurer Art Brown, and Financial Secretary Emory Evans as the sole member of a recent immigrant group. Kennedy demonstrated his sensitivity to the ethnic factor, however, in his appointments of the chief stewards for 1937: Jim Pepicello, once a member of the Molders Union at GE and the immigrant son of an Italian shepherd, Charles “Turk” Conti, and Joseph Kaminski, in addition to Robert Boettinger, filled out the executive board. Besides handling any unresolved grievances brought to them by stewards from the shop floor, chief stewards served as the lead organizers of their units, so it was crucial that they were people the rank and file could trust. Kennedy clearly used ethnicity in building that trust.7

With the election of Ray Konkel, a Polish-American, as Secretary in 1938, recent immigrant groups added to their representation in plant-wide offices. Further, Kaminski then replaced Piatkowski as sergeant-at-arms, further belying Ronald Schatz’s notion that no plant-wide offices were held by the recent immigrant group until the Second World War. Still, ethnicity was not the sole factor in accounting for union activism.8

Some who led in organizing Local 506 had a radical political and social perspective. Of course, the very idea of industrial unionism—contrasted to the traditional craft unionism modeled by many American Federation of Labor (AFL)–affiliated unions—still struck many in the 1930s as radical. Many advocates of rapid social change were drawn to the CIO movement; for communists, socialists, and others, workers’ successes in organizing mass industrial unions worked hand-in-glove with the need to create a broad base of support for significant social change. And, in the 1930s, many Americans sought a change from the excesses of the so-called free-market capitalism that had imposed the Great Depression upon them. Several of the founding and early members of UE had looked into AFL unionism but found it wanting in this era of financial crisis.9

Among those who rose to the organizing challenge from a leftist perspective was Louis “Red” Nicholson. Nicholson had acquired union experience on the railways. He also expressed openly his admiration for Eugene V. Debs, the railway union leader and frequent Socialist Party candidate for president of the United States. Initially hesitant to become a UE activist because he had been blacklisted in the railway industry, Nicholson overcame his fears and emerged as a leader. In 1938 he won election as chief plant steward and later served as chief local negotiator.10

Wilbur White and Mary Kuyler also approached unionism with a radical bent. Both served UE early and well, and both—according to White—belonged to the Communist Party during the union’s formative years. White made no secret of his membership. Kuyler, moreover, became the first woman on the union’s executive committee.11 White proved to be a valuable recruit. “The smartest guy in GE,” people often called him. And there was something to that. A toolmaker’s apprentice when he joined the union in 1937, White had completed the apprenticeship exam with the highest score ever recorded at the Erie Works. And “He worked like a dog for the union,” Bea Wise Anderson recalled years later. Yet, White may not have become a union activist if he hadn’t first been radicalized outside of the workplace. In reaction against his father’s Ku Klux Klan mentality, Wilbur White had used his presidency of a Methodist Church youth group, the Epworth League, to promote interracial understanding in the city. After some initial successes, however, White met intransigent resistance from church leaders, and his efforts failed. Disillusioned by the churchmen’s apparent hypocrisy, White cast about for an alternative avenue for his ideals. Influenced by a friend, George Baldwin, White considered joining the Socialist Party but decided instead to join the Erie branch of the CP, because the Communists seemed to have the better position on America’s race relations. They understood that the situation of African Americans was unique, and that blacks would not experience an increase in prosperity equal to everyone else’s as the tide of prosperity swelled, as other political parties maintained. So White, who had every reason to see himself as a member of the upwardly mobile aristocracy of labor, identified with unions, advancing the cause of human rights by advancing workers’ rights. Four months after UE 506 received its charter, he gave himself a birthday present and joined the union. Before 1937 ended, he chaired the local’s Education and Publications Committee. With Kennedy, Nicholson, White, and Kuyler, the leftist element influenced the new local.12

Another mainstay of UE organizing was Clara Williamson, whose ideological base remains unknown. The daughter of a miner and devout in both her apparent religious faith (she dressed very plainly) and her union loyalty, Clara sided with the progressive caucus during a temporary split in the local union during the Second World War. Yet, as a plant maintenance matron (janitress) in the late 1930s, Williamson, like Kennedy, used the mobility in her work duties to spread the union word. Moving from department to department, she talked up the union and dropped packets of UE literature in lavatories for others to pick up and distribute, a task that fell in the Refrigeration Division to Tom Brown, whose mother served as president of the Machinists’ local at the Marx Toy Works, just west of Erie, and to Charles Lacava. Similarly, the mobility accorded the scarcely supervised maintenance man C. Everett “Fat” Whipple worked to the union’s favor, and “MacMillen’s Gang,” the roving Powerhouse Department workers, began 1938 with total union membership. Such autonomous workers played a crucial role in the organizing campaign, as Ronald Schatz has observed.13

As chair of publications, White produced a series of leaflets on a hand-cranked mimeograph machine. Then, early in 1938, he began to publish 506’s first newspaper, The Spark, the title of the old Social Democratic Party’s paper in pre-revolutionary Russia, Iskra—but only when the union could muster the money for paper and ink. As often as not during those early days, White cranked out between 2,000 and 4,000 copies by himself. But the effort proved worthwhile. The paper raised workers’ awareness of happenings at GE, and it became increasingly popular after the addition of Ray Konkel’s column, “Behind the Racks of Building 12,” from the third issue. Konkel’s column contained tidbits and bombshells of information and gossip supplied to him by his fellow workers. Kennedy also contributed a column, which required substantial editing of his rambling, single-sentence style, but added to the paper’s appeal and credibility. Workers couldn’t get a copy of The Spark fast enough when they heard of a new issue. Often White had to return to the office and print more copies because of unexpected demand. In later years he concluded that his publishing of The Spark stood as his most important contribution in a lifetime of union, political, and human rights activism. He may have been right, for Local 506 membership mounted steadily and exceeded five hundred by early 1939.14

Meanwhile, the company played a final gambit: a watered-down unionism more in line with a corporate notion of industrial democracy than a CIO union. Following AFL president William Green’s rejection of a GE invitation to organize the corporation’s workers, GE had replaced the defeated AFL craft unions of the post–First World War era with the Works Council, noted above. After passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, which guaranteed workers the right to select their own representatives, the councils—whose workers’ representatives had been selected by management—were modified. In Erie and elsewhere, further changes in GE tactics resulted from the Supreme Court’s upholding in 1937 of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 that confirmed workers’ NIRA rights, prohibited company-supported “unions,” and provided enforcement machinery behind the law. Acknowledging the Works Council to be a company union, GE dissolved the council’s parent organization, the General Electric Industrial Union, in February 1938. UE’s membership surged, but soon an Employees’ Economic Association (EEA)—another incarnation of the company union—appeared and attracted some members. At this juncture, Fred Gardner, a UE International representative, arrived from New York with the aim of helping 506 obtain a majority vote against the EEA. With a sense of urgency, Red Nicholson’s Stewards’ Council now began to meet weekly. The final struggle for legal recognition of UE 506 as bargaining agent of Erie Works production employees began.15

TO THE CASUAL OBSERVER, ERIE MAY APPEAR an unlikely site for militant political or labor activity. Today, as the traveler descends from the ridges east and south of the lake that provides the city’s and the county’s names, vineyards and wooded tracts command the view, with the city of almost 102,000 spread out below. No skyscrapers proclaim the predominance of wealth and power in the community. The local media’s fervid focus upon the recreational Presque Isle Peninsula, which arches gracefully across the city’s harbor from the west, may lull the traveler into an illusion of Erie as a sleepy survivor of an earlier era, when Oliver Hazard Perry’s fleet set sail in Erie-built ships to gain victory over the British in the Battle of Lake Erie two centuries ago. Yet the rhythm of industry intrudes recurrently, and nowhere more frequently than in the eastern suburb of Lawrence Park, over which looms the massive bulk of GE’s Erie Works. At its height in the early 1950s the Erie Works employed some 21,000 people, but during the union organizing drive of 1937–40 the number stood at about 6,000. This employment of a substantial percentage of the area’s workforce ensured GE managers considerable influence in the area’s economic, political, and ...