![]()

Chapter 7

Hindmarsh PC (ed): Current Indications for Growth Hormone Therapy, ed 2, revised.

Endocr Dev. Basel, Karger, 2010, vol 18, pp 92-108

______________________

Current Indications for Growth Hormone Therapy for Children and Adolescents

Erick Richmonda · Alan D. Rogolb

aPediatric Endocrinology, National Children's Hospital, San José, Costa Rica; bPediatric Endocrinology, Riley Hospital, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Ind., and University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va., USA

______________________

Abstract

Growth hormone (GH) therapy has been appropriate for severely GH-deficient children and adolescents since the 1960s. Use for other conditions for which short stature was a component could not be seriously considered because of the small supply of human pituitary-derived hormone. That state changed remarkably in the mid-1980s because of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease associated with human pituitary tissue-derived hGH and the development of a (nearly) unlimited supply of recombinant, 22 kDa (r)hGH. The latter permitted all GH-deficient children to have access to treatment and one could design trials using rhGH to increase adult height in infants, children and adolescents with causes of short stature other than GH deficiency, as well as trials in adult GH-deficient men and women. Approved indications (US Food and Drug Administration) include: GH deficiency, chronic kidney disease, Turner syndrome, small-for-gestational age with failure to catch up to the normal height percentiles, Prader-Willi syndrome, idiopathic short stature, SHOX gene haploinsufficiency and Noonan syndrome (current to October 2008). The most common efficacy outcome in children is an increase in height velocity, although rhGH may prevent hypoglycemia in some infants with congenital hypopituitarism and increase the lean/fat ratio in most children - especially those with severe GH deficiency or Prader-Willi syndrome. Doses for adults, which affect body composition and health-related quality of life, are much lower than those for children, per kilogram of lean body mass. The safety profile is quite favorable with a small, but significant, incidence of raised intracranial pressure, scoliosis, muscle and joint discomfort, including slipped capital femoral epiphysis. The approval of rhGH therapy for short, non-GH-deficient children has validated the notion of GH sensitivity, which gives the opportunity to some children with significant short stature, but with normal stimulated GH test results, to benefit from rhGH therapy and perhaps attain an adult height within the normal range and appropriate for their mid-parental target height (genetic potential).

Copyright © 2010 S. Karger AG, Basel

Introduction

Human growth hormone (hGH) is a single-chain, 191-amino-acid protein of 22 kDa molecular weight. It is synthesized, stored and released from the somatotropes of the anterior pituitary gland. Multiple additional molecular variants, including a 20-kDa form produced by the gene deletion of 14 amino acids and other posttranslational isoforms, for example glycosylated and sulfated forms, of unknown physiological significance exist within the systemic circulation [1].

GH is relatively species-specific since only primate GH has efficacy in the human [2, 3]. None of the small trials with animal GH or enzymatically-produced fragments from animal GH showed growth-promoting efficacy in the human [4].

hGH was first extracted in the late 1940s [5] and administered to humans beginning in 1958 [6, 7]. Treatment of both children and adults was reported in that first clinical trial, although the latter took a number of years for confirmation of efficacy since so little hormone was available (essentially one pituitary per child per day). Thus, in the early years only profoundly GH-deficient children received treatment. Much of the time so little hormone was available that many children were treated 6 or 9 months a year permitting other, equally needy, children to reap some benefit from hGH therapy.

That all changed in the early 1980s when it became clear that Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease could be transmitted by human brain tissue and recombinant (r)hGH became available [8]. At that time a seemingly endless supply of the pure 22-kDa hormone permitted all GH-deficient children to have access to treatment and one could now design trials using rhGH to increase adult height in infants, children and adolescents with causes of short stature other than GH deficiency, as well as trials in adult GH-deficient men and women. The next 20 years led to at least 7 additional indications in children and 3 new ones in adults (table 1).

hGH is administered to promote linear growth in short children. The following are the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved indications for GH (current to October 2008) and in parentheses the indications approved in Europe (E) by the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMEA).

The most common efficacy outcome in infants, children and adolescents is an increase in linear growth, although rhGH may prevent hypoglycemia in some infants with congenital hypopituitarism and increase the lean/fat ratio in children with the Prader-Willi syndrome (see below).

The dose-response curve for height gain versus dose of rhGH (log scale) is rather flat in those with GH deficiency [9], even through the much higher doses (including 100 μg/kg/day) administered more recently [10]. The dose for adults which affects body composition and health-related quality of life are much lower per kilogram of body mass.

Table 1. Approved indications for GH therapy in children and adults in the USA and Europe (E)

| Children |

| Growth hormone deficiency (E) |

| Chronic kidney disease (E) |

| Turner syndrome (E) |

| Small-for-gestational age infants who fail to catch up to the normal growth percentiles (E) |

| Prader-Willi syndrome (E) |

| Idiopathic short stature |

| SHOX gene haploinsufficiency (E) |

| Noonan syndrome |

| Adults |

| Growth hormone deficiency (E) |

| HIV/AIDS wasting |

| Short bowel syndrome |

In this review, the studies that were selected for analysis were mainly randomized controlled studies, with the larger number of patients and the longest treatment duration of the available publications.

Growth Hormone Deficiency (GHD)

The administration of GH to treat children with sort stature resulting from GHD or GH insufficiency has now accrued over 40 years of clinical experience. In 1985, the US FDA approved the use of rhGH for the treatment of GHD and remains the primary indication for GH treatment in childhood. GHD is fundamentally a clinical diagnosis, based upon auxologic features. Assessment of laboratory tests, whether static, for example the measurement of IGF-1 and IGFBP-3, or dynamic, for example, secretagogue-stimulated GH secretion is confirmatory [11]. Radiologic evaluation of the hypothalamus and pituitary (CT scan or MRI) is helpful in patients with suspected congenital GHD or to detect space-occupying lesions (see Chapters 1 and 3 for fuller discussion of these points).

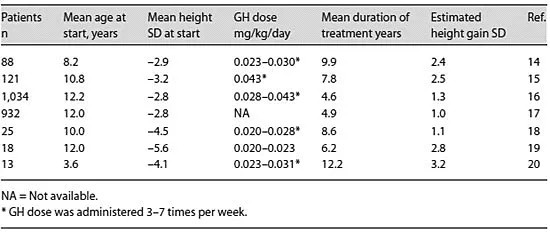

The primary objectives of therapy of GHD are normalization of height during childhood and attainment of adult height within the normal range. The greater efficacy demonstrated in recent large international databases [12, 13] compared with the initial studies of GH treatment in GHD patients (table 2) probably reflects the combined effects of the higher GH dose, the more physiologic injection frequency, and the younger age at initiation of treatment. Current consensus guidelines recommend a dose in the range of 0.025-0.05 mg/kg/day [21, 22]. Under special circumstances, higher doses may be required, including adolescents with late diagnosis and diminished period of time for catch-up growth [23]. Recently it has been proposed that IGF-1-based GH dosing may improve growth responses, although at higher average GH doses [24].

Table 2. GH trials in children with GHD

Significant side effects of GH treatment in children are uncommon. These include idiopathic intracranial hypertension, prepubertal gynecomastia, arthralgia, and edema [21, 22]. Management of these side effects may include either transient reduction of dosage or temporary discontinuation of GH. In the absence of other risk factors, there is no evidence that the risk of leukemia, brain tumor recurrence, slipped capital femoral epiphysis or diabetes are increased in recipients of long-term GH treatment.

GHD may or not persist into adulthood. After the...