![]()

Chapter 12

Knight SJL (ed): Genetics of Mental Retardation.

Monogr Hum Genet. Basel, Karger, 2010, vol 18, pp 137–150

______________________

Chromosome 22q13 Rearrangements Causing Global Developmental Delay and Autistic Spectrum Disorder

M.C. Bonagliaa · R. Giordaa · R. Cicconeb · O. Zuffardib, c

aEugenio Medea Scientific Institute, Bosisio Parini, Lecco, bBiologia Generale e Genetica Medica, Università di Pavia, Pavia, cFondazione IRCCS C Mondino, Pavia, Italy

______________________

Abstract

The constitutional deletion of 22q13 is an example of a new microdeletion syndrome, known as the 22q13.3 deletion syndrome, telomeric 22q13 monosomy syndrome, or Phelan-McDermid syndrome (OMIM #606232). It was identified by the detection of a cytogenetic rearrangement in advance of its clinical definition. The clinical definition came following the introduction of new methods aimed at checking telomere integrity which confirmed the previously observed phenotype consisting of global developmental delay, generalized hypotonia, absent or delayed speech, and normal to advanced growth. Since then, continued improvements in molecular cytogenetic techniques have increased the diagnostic yield of 22q13 deletions further leading to improved definition of the clinical phenotype, although the incidence of the syndrome has still to be estimated. The deletion occurs with equal frequency in males and females and it has been reported in mosaic and non-mosaic forms; it may occur de novo or be inherited and be associated with ring chromosome 22 and in rare cases with proximal inverted duplications. Rare terminal duplications of 22q13 have also been found. Haploinsufficiency of the SHANK3/ProSAP2 gene, less than 200 kb proximal to the chromosome 22q telomere, is very likely the cause of the major neurological features associated with 22q13 deletion, since the gene is always found disrupted or deleted in patients with the syndrome and a recurrent breakpoint within SHANK3, mediated by a repeated non-B DNA-forming sequence, has been identified in several patients. Owing to its emerging role in neuropsychiatric disorders and the overlap of phenotypes between autism and 22q13.3 deletion syndrome, SHANK3 became eligible for mutation screening in patients with autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) and several studies have discovered de novo mutations in such patients. In this chapter, we review the current knowledge regarding pathological copy number variants of 22q13.3 in developmental delay and ASD.

Copyright © 2010 S. Karger AG, Basel

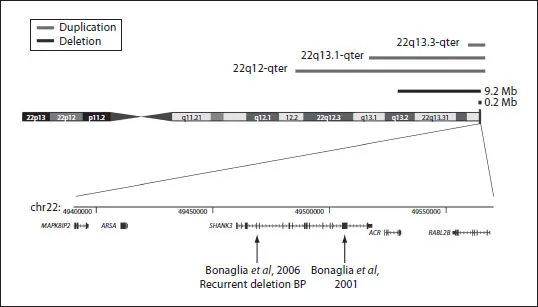

In clinical cytogenetics, the constitutional deletion of 22q13 represents an example of a new microdeletion syndrome, namely the 22q13.3 deletion syndrome, also called telomeric 22q13 monosomy syndrome and Phelan-McDermid syndrome (OMIM #606232) [1]. However, the syndrome was not recognized as a clinical entity until the identification of common features in patients with 22q distal deletions [2-4]. Patients with 22q13.3 terminal deletions that encompass the SHANK3 (or ProSAP2) gene, or with disruption [5-7] or loss of function mutations of SHANK3[8], result in a common neurological phenotype of neonatal hypotonia, global developmental delay, normal to accelerated growth, absent to severely delayed speech, behavioural features consistent with disorders of the autistic spectrum [8, 9] and minor facial dysmorphisms. In contrast to other known subtelomeric terminal deletions resulting in a clinical phenotype (e.g. 1p36, 9q34, 3q26, 2q37), the 22q13 deletion represents the first example of a terminal deletion with a recurrent breakpoint [5, 7, 8, 10, 11] in addition to non-recurrent breakpoints occurring at multiple sites between 140 kb and 9 Mb from the 22q telomere (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Ideogram of human chromosome 22 showing above: the extent of 22q13 deletions ranging from 200 kb to more than 9 Mb (horizontal black lines) and also the extent of terminal 22q13 duplications (horizontal grey line) and below: detail of the distal 200 kb of 22q; the position and structure of several genes, including SHANK3, is shown. Arrows indicate the position of the breakpoint in a balanced t(12;22) [6] and of the breakpoint (in intron 8 of SHANK3) of a recurrent 140 kb terminal 22q deletion [7].

History of the Chromosome 22q13 Deletion Syndrome

A pure terminal chromosome 22q deletion was first reported in 1985 [2] in a 14-year-old boy with profound mental retardation, absent speech, minor dysmorphic features, but normal tone [2]. Later on, Phelan et al. [3] reported that generalized hypotonia was also a constant finding. With only a very few patients described, this disorder remained relatively undefined in the medical literature until 1994 when Nesslinger et al. [4] described seven patients with microscopically visible distal deletions involving 22q13.3 sharing an overlapping phenotype characterized by developmental delay, hypotonia, delay in expressive speech and minor facial dysmorphisms. Accelerated growth was reported in some of them. The critical region for the deletion was narrowed to the terminal 5 Mb distal to the ARSA gene (the most distal locus on chromosome 22q at that time), but no strict correlation between deletion size and symptoms could be established.

The 22q13 deletion was recognized as a distinct clinical entity and initially named 22q13 deletion syndrome in 2001, when the clinical information for 37 new individuals with deletions of 22q13 was compared with the clinical features of 24 previously reported cases [1]. The previously observed phenotype (global developmental delay, generalized hypotonia, absent or delayed speech, and normal to advanced growth) was confirmed, but it was observed that the severity of the symptoms varied widely. The authors also identified common minor craniofacial features consisting of dolichocephaly (50%), ptosis (43%), epicanthic folds (39%), prominent/dysplastic ears (58%) and pointed chin (52%). In addition, dysplastic toe nails, susceptibility to hyperthermia due to reduced perspiration, and increased tolerance to pain were frequently noticed.

It was the introduction of new methods aimed at checking telomere integrity, about 15 years ago, that led to the definition of the 22q13.3 distal deletion syndrome as well as other new malformation syndromes [12-14] (see also chapter 3 and chapter 9). Flint and colleagues [12] detected the first cryptic 22q deletion while screening for the abnormal inheritance of subtelomeric DNA polymorphisms in subjects with mental retardation. The patient NT [12] showed mild mental retardation (MR) with an intelligence quotient (IQ) of 64 and delayed speech with a 25-point discrepancy between verbal IQ (50) and performance IQ (75) at the age of 12 years, in the absence of abnormal physical findings or dysmorphic features [12]. Since then, more than 100 instances of 22q distal deletion, not detectable by conventional cytogenetic techniques, have been found. Some were detected while screening for cryptic subtelomeric rearrangements in patients with mental retardation [15]. Others, with a generic ‘chromosomal phenotype’, were detected during exclusion of a deletion at the DiGeorge/velocardiofacial region [16-18]. In fact, commercially available DiGeorge probes serendipitously include 22q distal probes as a control. This genetic test is frequently requested whenever a patient presents with mental retardation in absence of recognizable phenotype although, a posteriori, the phenotypes of DiGeorge/Velocardiofacial and 22q13 deletion syndromes are rather different.

Continued improvements in molecular cytogenetics have further increased the diagnostic yield of 22q13 deletions. As a consequence, the clinical observation of a growing number of subjects with 22q13 deletion has allowed a better definition of the syndrome’s phenotype. A specific behavioural phenotype, including social traits characteristic of the autistic spectrum, such as poor eye contact, stereotypic movements, and decreased socialization [7, 16, 18, 19] have been described in children with the syndrome. Furthermore, the 22q13 deletion has been shown to be one of the most common among the rare chromosomal abnormalities (reviewed in [20]) reported on more than one occasion in subjects with ASD [19, 21]. The proportion of patients with 22q13 deletion syndrome and ASD has not been calculated yet, but is probably very high [20].

Molecular Diagnosis of 22q13 Microdeletion Syndrome

The molecular diagnosis of the syndrome is confirmed by the demonstration of a deletion or disruption of chromosome 22q13.3. With the introduction of subtelomeric FISH tests, the 22q13.3 deletion has become recognized as relatively frequent, and it ha...