eBook - ePub

Periodontal Disease

- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Periodontal Disease

About this book

Our understanding of the etiopathology of periodontal disease has changed greatly over the last decade. The huge diversity of species within the microbial biofilm and the enormous multi-layered complexity of the innate, inflammatory and adaptive immune responses generated in response to it warrant study and discussion. Comprising reviews from renowned experts in the field, this book presents a comprehensible overview of this exciting and pertinent subject matter. It provides new insights into the structure and composition of subgingival biofilms and the nature of the extracellular matrix. Further, a summary of current understanding of subgingival microbial diversity and an overview of experimental models used to dissect the functional characteristics of subgingival communities are presented. Other articles discuss the innate cellular and neutrophil responses to the periodontal biofilm. The role of antimicrobial peptides in the host response to biofilm bacteria and modern approaches to nonsurgical biofilm management are also discussed. Finally, this volume addresses advances in antibiotic use and proposes a paradigm shift in the pharmacological approach to periodontal disease management.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Periodontal Disease by D. F. Kinane,A. Mombelli,D.F., Kinane,A., Mombelli, P. T. Sharpe,P.T., Sharpe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Dentistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Kinane DF, Mombelli A (eds): Periodontal Disease. Front Oral Biol. Basel, Karger, 2012, vol 15, pp 56-83

______________________

Neutrophils in Periodontal Inflammation

David A. Scotta,b · Jennifer L. Kraussa

aCenter for Oral Health and Systemic Disease and bDepartment of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Louisville, Louisville, Ky., USA

______________________

Abstract

Neutrophils (also called polymorphonuclear leukocytes) are the most abundant leukocytes whose primary purpose as anti-microbial professional phagocytes is to kill extracellular pathogens. Neutrophils and macrophages are phagocytic cell types that along with other cells effectively link the innate and adaptive arms of the immune response, and help promote inflammatory resolution and tissue healing. Found extensively within the gingival crevice and epithelium, neutrophils are considered the key protective cell type in the periodontal tissues. Histopathology of periodontal lesions indicates that neutrophils form a ‘wall’ between the junctional epithelium and the pathogenrich dental plaque which functions as a robust anti-microbial secretory structure and as a unified phagocytic apparatus. However, neutrophil protection is not without cost and is always considered a two-edged sword in that overactivity of neutrophils can cause tissue damage and prolong the extent and severity of inflammatory periodontal diseases. This review will cover the innate and inflammatory functions of neutrophils, and describe the importance and utility of neutrophils to the host response and the integrity of the periodontium in health and disease.

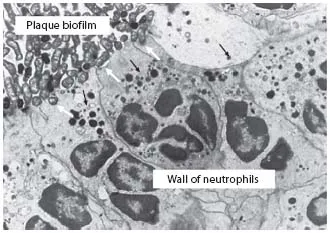

Copyright © 2012 S. Karger AG, Basel

Neutrophils, the most abundant of the leukocytes, are myeloid-derived anti-microbial professional phagocytes that can also kill pathogens extracellularly, link the innate and adaptive arms of the immune response, and help promote inflammatory resolution and tissue healing. Found extensively within the gingival crevice and epithelium, neutrophils are considered the key protective cell type in the periodontal tissues [1-4]. Intriguingly, histological evidence (fig. 1) suggests that neutrophils form a ‘wall’ between the junctional epithelium and the pathogen-rich dental plaque [2, 3]. Providing more than a mere barrier function, this anti-microbial wall is thought to function in two ways: as a robust secretory structure (reactive oxygen species, ROS, and bacteriocidal proteins) and as a unified phagocytic apparatus. In other words, the protective power lies in the synergic structure. However, this protection is not without cost, as considerable observational, genetic and experimental data have established a clear association between neutrophil infiltration into the periodontal tissues and the severity and progression of inflammatory periodontal diseases [3, 5-7].

Fig. 1. Interface of bacterial plaque and crevicular neutrophils within the periodontal pocket. Neutrophils in the periodontal pocket forming a wall against the plaque biofilm. Neutrophils cannot engulf the large biofilm structure in vivo. The formation of a wall against the biofilm may be a protective mechanism. Nevertheless, an attempt is made to engulf the surface layer of this biofilm (white arrows). During this process of frustrated phagocytosis, enzymes within neutrophil lysosomal granules (black arrows), products of the oxidative burst, and other proinflammatory substances may be released directly into the pocket and/or the underlying tissue, where they have a predominantly destructive effect. Figure and text reproduced (with permission) from Ryder [3].

Gene Activity in Neutrophils

While in the bone marrow, neutrophils are transcriptionally and translationally active. During this ‘differentiation program’, neutrophils are furnished with a large armory of pre-formed signaling and anti-microbial molecules, stored in granules [8]. In the region of 5-10 × 1010 new neutrophils are produced daily [9]. Differentiation occurs over approximately 14 days, after which neutrophils enter the circulation as mature, essentially, terminally differentiated cells that have been traditionally considered to be transcriptionally quiescent. However, recent evidence shows that upon leaving the vasculature for infected or inflamed tissues, such as the periodontium, neutrophils undergo a second burst of transcriptional activity, in a process referred to as the ‘immune response program’ [8]. During the immune response program, cytokines and chemokines, molecules that direct the resolution of inflammation and promote healing, are the prominent translational products [8]. While the relevance of neutrophil gene activity in the periodontal tissues has yet to be established, it is important to note that the immune response program renders periodontal neutrophils capable of de novo synthesis of multiple factors that may influence disease progression. In other words, periodontal neutrophils are not functionally reliant solely on their granule contents, as previously thought.

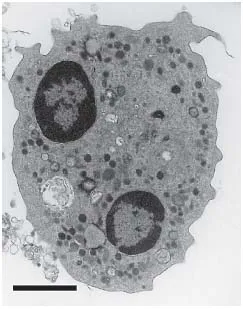

Fig. 2. TEM image of a typical human neutrophil showing intracellular membrane-bound compartments.The multi-lobed nucleus and granule-dense cytoplasm are clearly apparent. Image taken from Guzik et al. [14]. Scale bar = 2 μm.

Neutrophil Granule Diversity

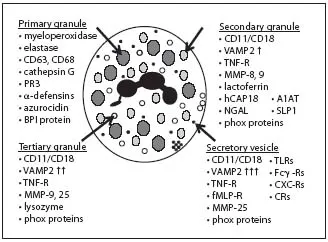

A transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image highlighting a typical highly granular human neutrophil is presented in figure 2. The variant membrane-bound intracellular granular structures of neutrophils - known as primary (azurophilic), secondary (specific) and tertiary (gelatinase) granules, as well as the secretory vesicles - are traditionally distinguished by granule-specific biomarker proteins (fig. 3). However, a huge degree of heterogeneity in neutrophil granule content is now appreciated [8]. Granule formation occurs as a continuum, with the considerable heterogeneity explained by the ‘targeting-by-timing hypothesis’. This states that different granule proteins are expressed at different stages of the differentiation program, and that these temporally controlled granule proteins are diverted from the constitutive secretory pathway and packaged into granules as and when they are made [8, 10]. Thus, the contents of granules packaged late in the differentiation program will be very different than those packaged early in the differentiation program. The ability of the differing granule sub-types to fuse with the neutrophil cell membrane and, thus, degranulate into the extracellular environment or populate the neutrophil cell surface (as opposed to fusing with the phagosomal membrane) is similarly temporally controlled. v-SNAREs [vesicle-soluble NSF (N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor/fusion protein) attachment protein receptors] are produced in larger amounts as the differentiation program progresses, with vesicle-associated membrane protein-2 (VAMP-2) the best characterized [8, 11]. v-SNAREs, such as VAMP-2, enable granule membrane fusion with the cell membrane. Thus, the targeting-by-timing hypothesis also provides an explanation for the alternate functions of the various neutrophil granule compartments. The last granules to form in the bone marrow - the secretory vesicles - contain the greatest concentration of v-SNAREs, and thus they control neutrophil environmental responsiveness and firm adhesion to activated vascular endothelia in the periodontium and elsewhere. The tertiary granules facilitate extravasation via matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-mediated degradation of the basement membrane (without release of the degradative neutrophil serine proteases, i.e. cathepsin G, neutrophil elastase and proteinase 3). The secondary granules promote phagocytotic capacity, while primary and secondary granules each contribute the major anti-microbial arsenal [8, 12, 13]. While not an absolute, then, the predominant proteinaceous contents of the various intracellular membrane-bound compartments in human neutrophils are presented in figure 3. The combination of proteases shown in figure 3 (in conjunction with ROS) is capable of destroying most components of the periodontal soft tissues, not limited to collagen and collagen-derived peptides, including the organic component of alveolar bone, fibrinogen, fibronectin, laminin and elastin.

Fig. 3. Contents of the intracellular membrane-bound compartments of human neutrophils. CD63 and CD68 are degranulation markers. VAMP2 is key in granule membrane-cell membrane fusion and exocytosis. Phox proteins are NADPH oxidase subunits involved in ROS production (Gp91phox; p22phox). PR3 = Proteinase 3; TLRs = TLR-1, 2, 4, 6 and 8; CXC-Rs = CXC receptors 1, 2 and 4 as well as chemokine receptors 1, 2 and 3; CRs = complement receptor 1 (CD35), c1qR. Data presented are combined from various reports [8, 12, 13, 15].

As...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Front Matter

- Subgingival Biofilm Structure

- Microbial Diversity and Interactions in Subgingival Biofilm Communities

- Innate Cellular Responses to the Periodontal Biofilm

- Neutrophils in Periodontal Inflammation

- Antimicrobial Peptides in Periodontal Innate Defense

- Modern Approaches to Non-Surgical Biofilm Management

- Animal Models to Study Host-Bacteria Interactions Involved in Periodontitis

- Antimicrobial Advances in Treating Periodontal Diseases

- Regenerative Periodontal Therapy

- Paradigm Shift in the Pharmacological Management of Periodontal Diseases

- Author Index

- Subject Index